In First Real-World Experiment, Red Seaweed Cuts Methane In Cows By More Than Half

11:11 minutes

Methane emissions are a hot topic—largely because it’s a big contributor to climate change. Methane makes up about 10% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. 27% of that comes from the burps of ruminant animals, such as cows.

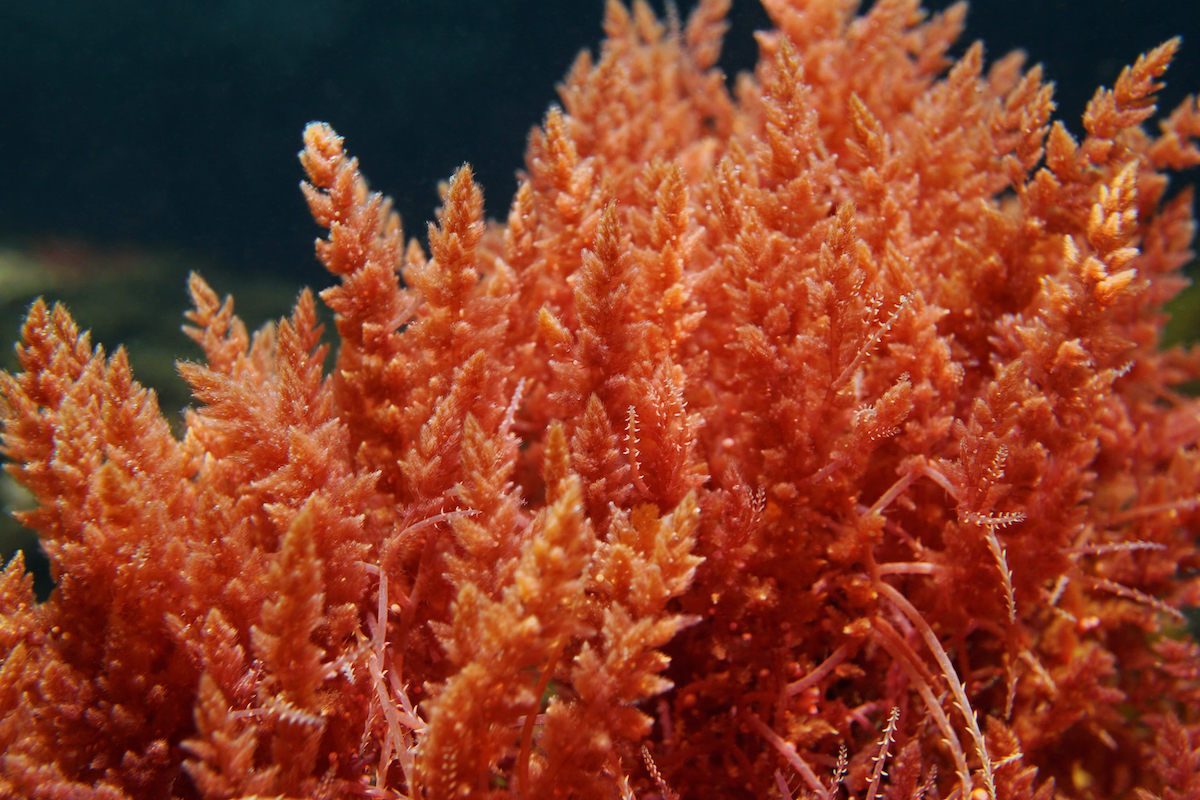

In April, Science Friday did a story about research that showed promising results when steers were fed small amounts of the red algae Asparagopsis in their diets. At the time, these experiments were only done in a closely controlled university setting. Now, the first real-world study on a working dairy farm has been completed. The results? Methane released by the seaweed-eating cows was 52% less on average than their non-seaweed-munching counterparts.

Coming on the heels of the Biden administration’s methane emissions reduction plan, SciFri producer Kathleen Davis sits down with three key players in this milestone: Joan Salwen, CEO of Blue Ocean Barns in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, the company that produces the Asparagopsis seaweed powder; Dr. Breanna Roque, animal science consultant at Blue Ocean Barns in Townsville, Queensland, Australia; and Albert Straus, founder and CEO of Straus Family Creamery in Marshall, California.

This week, Science Friday celebrated 30 years on the air!

We are overwhelmed with gratitude for these 30 incredible years of awe-inspiring and honest conversations with scientists, researchers, writers, policy-makers, educators, and experts. And immensely grateful for you, for 30 years of listener calls and questions that have encouraged our curiosity and driven our programming. Sharing our time with you each Friday has been a gift. Thank you!

But there is more work to do, more stories to be told, and more research to be explored.

Listeners support our work by making donations—big or small. By making a gift, you help us prepare for our future, protect us from uncertainty, and enable us to take risks like launching a new podcast, offering a free event, and providing free educational materials.

The need for fact-based science news is undeniable. Make a donation today, celebrate our 30-year history and be a champion of the next 30 years ahead!

Your support makes a difference.

Thank you,

Ira Flatow and the Staff and Board of Science Friday

Joan Salwen is CEO of Blue Ocean Barns in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii.

Breanna Roque is an animal science consultant at Blue Ocean Barns in Townsville in Queensland, Australia.

Albert Straus is founder and CEO of the Straus Family Creamery in Marshall, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Earlier this year, we brought you a story about how feeding cows seaweed– yes, seaweed– might be a secret to lowering methane emissions. You see, cows are notorious for releasing gas, methane, and they’re a large contributor to global warming.

Early research showed giving cows just a little bit of seaweed in their diets could reduce that amount of methane. Well, now we’ve got new news from this research team, and it turns out this is working better than expected. Joining me now is SciFri producer Kathleen Davis, who first brought us that story. Hi, Kathleen.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Hey there, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Now tell me about this update.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: When we covered this story in April, this experiment with seaweed and cows was really promising, but it was only proven to work in a very controlled university setting. And as you may know, Ira, testing something like this in real life, well, there’s a lot that can go wrong.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, yeah. Sure makes sense to me.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And we are talking about a very specific kind of red seaweed being fed to cows. It is called asparagopsis.

IRA FLATOW: Asparo what? It sounds like something I’d sprinkle balsamic vinegar on.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yes. And a couple of big reminders if you don’t remember this first story that we talked about this. These cows got a little bit of seaweed powder in their feed every day. The cows don’t seem to notice that it’s there, and it doesn’t affect the taste of the dairy products made from cow’s milk.

IRA FLATOW: So no seaweed flavored ice cream then?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: No. No. Just normal tasting milk and meat. This trial that we’re talking about today was the first to happen on a real working dairy farm and guess what.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll bite. What?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: The cows who ate a tiny bit of seaweed powder released half the methane that they normally would in their burps. For some cows, it was over 85% reduction.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that is really good news, isn’t it?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Yeah, it sure is, and we love to follow cool research here at Science Friday, especially when it’s something really important like this. So I caught up with three of the key players involved in this update. Dr. Brianna Roque is an animal science consultant at Blue Ocean Barns in Townsville, Queensland, Australia. Joan Salwen is CEO of Blue Ocean Barns in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. And Albert Straus is founder and CEO of Straus Family Creamery in Marshall, California. And I started by asking Brianna, the research brains of the operation, how they can actually measure that methane release.

BRIANNA ROQUE: Yeah, there’s quite a few different measurement techniques what I’ve used as a graduate student and now as a consultant. It’s what’s called a green feed machine. And what this machine does is it’s feed incentivized, so the cow voluntarily enters. When a little bit of feed is dropped down, she can put her head in, eat. We like to keep drops flowing between three to five minutes to keep that cow in there as long as possible.

And as she’s eating this bait feed, she’s also eructating or burping up greenhouse gases. So carbon dioxide and methane is usually what we focus on. One of the downsides and what we’ve been able to be flexible with is those are spot– what’s called spot measurements, so you get it only at that point in time.

So what we do is we allow the cows to come in multiple times per day also every single day. And then what we do is we average those methane emissions over the course of a 24-hour period as well as with this project we use to 10-day experimental period. This way we’re not over or underestimating any type of greenhouse gases that are coming from each cow.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Now, Joan, you are behind the company that produces this seaweed powder that was used by Albert’s cows in this study, and one thing that I thought was really interesting is that you’re marketing this for use in dairy cows, not in cattle, not beef cows. Why is this?

JOAN SALWEN: Thanks for asking. Our product is equally effective in both dairy and beef cattle. The dairy industry has a great opportunity in that dairy cattle have to be milked at least twice per day. And so they’re handled a lot, and they are they’re used to human beings being around them. And they’re in some ways more gentle and more trainable to get into the green feed machine. There are a lot of fun. They’re beautiful. And so dairy cattle have been a really good place for us to start.

It’s also not well known that per head, a dairy cow actually does burp more methane than a big old Texas longhorn or whatever, and it’s because that she’s eating a great deal of feed in order to provide nutritious milk for the rest of us. So the per head emissions per cow is pretty compelling, and so a lot of the early work that we’ve done has been with dairy cattle. That being said, Brianna also conducted a beautiful trial using beef steers for a long period of time, 147 days, so this is easily been used and has great utility in both kinds of cattle.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Now I want to take up to this topic of scalability. Just this week, President Biden announced a plan to tackle methane emissions across various industries including the agricultural sector. Now the USDA according to this plan has been ordered to work with farmers to identify voluntary approaches to combat this issue. Joan, do you think that asparagopsis could play a role here?

JOAN SALWEN: There’s no question that asparagopsis can play a huge role here. One of the things that is so beautiful about this additive is that it works in the cow the day she eats it. So the very first day that a cow is on a diet that includes this red seaweed, she’s on her way. So that’s very exciting because a lot of the things that are going to need to be done to reduce methane emissions are going to take a lot of time. So there is no question that farmers can play a big role, and cows can be an important part of the solution of climate change.

We’re able to cultivate this plant now in a way that does allow for scale, and we’re able to in a very small geographic footprint create a very high yield per acre of this plant such that we could feed all of the cows and cattle in the United States on a plot of land that is smaller than O’Hare Airport. That’s very tangible. That’s within our reach. We can do this, and we will during this decade.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Now, Albert, you have made a large part of your brand of being a dairy farmer that you’re a good steward of the environment, that you care about these things. But do you think that other dairy farmers are going to get on board with giving their cows the seaweed powder?

ALBERT STRAUS: So I think that farmers have not been receiving the true cost of food that they’re producing. So by doing these practices and showing the public that their benefit that they should be paying the true cost of what the cost for a gallon of milk or a cup of yogurt is something that economically farmers will benefit by doing the right practices and beneficial practices. And all these sustainability practices have a return on investment and have a positive cash flow for farms. Of the remaining farms in Marin and Sonoma County, San Francisco, 85% of them are certified organic. And so I feel very optimistic that we can show farmers the way and help them be sustainable and answer to climate change.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Joan, I’d like to follow up with you. Do you think that this is going to catch on, and do you think that some dairy farmers are going to need some convincing?

JOAN SALWEN: I think this is going to catch on. We’re hearing from a lot of corporations and food companies who really want to play a role in reducing the greenhouse gas emissions within their supply chains. They want to be helpful to their farmers. So as long as there are farmers like Albert who are using it on their farms and telling stories to their neighbors and to the associations they belong to and using their influence with farmers and we’re partnering with enlightened food companies who are very serious about reducing their impact on the climate, I’m pretty sure this is going to catch on.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Brianna, I want to give you my last question. What are the things that you would love to know about how asparagopsis works, or what are the unanswered questions that you would love to find the answers to?

BRIANNA ROQUE: Yeah. There’s lots to do. This is fairly new in the world of research, and just to give a brief summary, we’ve shown that it works to significantly reduce methane emissions. We’ve shown that it works on farm, which is very exciting. We’ve seen that it works for at least 21 weeks, almost half a year. We’re getting there.

But there are some gaps. There are some unanswered questions that we should focus on. I think the first being is I’d really like to see this application go through a full lactation cycle. Can we show that dairy cows eating asparagopsis– can they reduce methane emissions throughout at least a full lactation cycle and beyond.

The other gap that I think is very interesting is we do see in some studies an increase in feed efficiency. So whether that’s through a reduced feed intake and a maintenance of either milk or meat products, or we’re seeing on the flip side a maintenance of feed intake with an increase in milk or meat production. And we’ve seen that time and time again, and we need to see a larger scale. Is that also scalable?

And I think in terms of getting farmers on board, if we can show that asparagopsis can not only reduce methane emissions but it also could increase the productivity of their farm, I think that is really is what may get farmers on board to want to use this and implement it. One of the issues we come across in agriculture is the profit margins can be pretty slim for some farmers, and so how can we provide a product that is not only environmentally beneficial but also financially.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Dr. Brianna Roque is an animal science consultant at Blue Ocean Barns. She is based in Townsville, Queensland, Australia. Joan Salwen is CEO of Blue Ocean Barns in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. And Albert Straus is founder and CEO of Straus Family Creamery in Marshall, California. Thank you all for joining me today.

BRIANNA ROQUE: Thank you.

ALBERT STRAUS: Thank you, Kathleen.

JOAN SALWEN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And Thanks to Sci Fri producer Kathleen Davis for bringing us that moo-ving story.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.