How The Puget Sound Region Is Reckoning With Disappearing Salmon

Journalist Lynda Mapes speaks with local tribe leaders and conservation groups as they grapple with the loss of symbolic aquatic life.

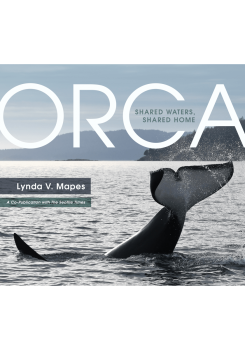

The following is an excerpt from Orca: Shared Waters, Shared Home by Lynda Mapes.

Orca: Shared Waters, Shared Home

On a cold, foggy morning in the summer of 2019, I made my way to a boat ramp, hard by homeless encampments and under the roaring traffic of a highway overpass in Seattle, to watch and talk with Muckleshoot tribal members bringing in their catch. Some ninety boats turned out for what was only a twelve-hour opening—all the river could support for this treaty-protected fishery that year.

But there they were: big, beautiful chinook, still silver bright from the sea. In this setting, they seemed as unlikely and out of time as dinosaurs. And yet these people, and these fish, the river’s first inhabitants, were still here.

The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe has invested heavily in the Green-Duwamish River, and their treaty entitles them to half the salmon catch. But half of next to nothing is just about nothing. The catch was so small in this briefest of openings that there would not be another fishery allowed that season, despite the treaty’s promise. These losses were not so much intentional as not thought about. They didn’t matter to the settlers who remade this place. Historian Coll Thrush at the University of British Columbia, in his superb article “City of the Changers” in Pacific Historical Review, notes the remarkable lack of concern as newcomers blew up, carved up, replumbed, and remade the lands and waters where they had only recently arrived.

“The people who did all this thought they were improving on nature; they thought they were making it better and more efficient,” Thrush told me.

“They really thought they were doing the right thing, and they were completely dismissive of the effects on the salmon and indigenous people, which are really the same story. You had indigenous people starving within sight of the Smith Tower [in Seattle]; there were no fish.”

Thrush grew up in Auburn and knows its landscape. He sees an unreconciled history held in this land and its people. “I feel like Seattle and Puget Sound is still coming to terms with its own past and the consequences of that past,” Thrush said. “We are all inside that story; we are all part of it—we have a right to speak of it and a responsibility to speak of it.”

These lands and waters also speak for themselves, in layers of history and time, read in pollen records and shell middens, in extirpation, in displacement and persistence. And even in the memories of matriarch orcas like L25, still here through more than eight decades.

“The orcas—they know; they have seen it all,” Thrush said. “They haven’t seen the dam on Eagle Gorge on the Green, but they have seen its effects; we are past the point of thinking they are ‘just animals’ without consciousness. What might the story look like from their perspective?”

Long-lived, the southern resident orcas are repositories of memory and experience, and they have witnessed so much change in less than two generations. “They have their own histories that they carry,” Thrush said. “They are an archive.”

It is dizzying to think of the changes one extended family of orcas has been forced to contend with. L25 was born in about 1928, before the first dam on the Columbia, Rock Island, was built, and Bonneville Dam was still another decade away. There was no Hanford Nuclear Reservation, no Grand Coulee Dam; there were no dams on the Lower Snake River. The state’s population was about 1.5 million people.

Over L25’s lifetime, the state’s population has grown to nearly 8 million, with no end of growth in sight. As the region booms, salmon and orcas are in a race against time. Under siege since the settlers arrived with their draglines and steam shovels and suction-pump dredges, the threats to the southern residents’ home waters have metastasized.

“I don’t want to see my culture in a tank.”

Beyond central Puget Sound, where the destruction started, are some of the Puget Sound region’s fastest-developing landscapes: the suburbs. More growth means more people and, depending on how growth is managed, more pollution and more runoff, as forests and open spaces that absorb the heavy rains and filter pollution are paved over or converted to housing, shopping centers, office parks, and all the rest. With the urban core already built out and devoured, what is happening here now is destroying the best of what is left.

Regional housing shortages and skyrocketing housing costs make the problem worse. The burgeoning job centers in Seattle and the east side of Lake Washington have brought more and more people chasing six-figure tech work. That has pushed people to places like Granite Falls, 42 miles north of Seattle in Snohomish County. This city, near the Stillaguamish River, notched the second-fastest rate of growth among cities in the four-county central Puget Sound region of Snohomish, King, Pierce, and Kitsap Counties in 2018–2019. One reason is affordability. The price per square foot of a home that year in Granite Falls was less than half that in Seattle.

I went to go see what money buys for people flocking to the suburbs to enjoy a lifestyle with more space for less money. “Sold out of inventory, more coming soon!” read the sign stuck in the ground at Suncrest Farms, a new housing development in Granite Falls. Swing sets and backyards beckoned.

Just across the street was a pasture, where a lone horse up to its belly in spring daisies swished its tail. How much longer, I wondered, watching that horse, would this open field, part of a classic old farm with its meadow transitioning to tall firs, be there? How long before it, too, would become a subdivision? In these parts, a happy horse in a daisy-flecked meadow looked as endangered to me as a Puget Sound chinook or southern resident orca.

Just down the road from these burgeoning housing developments was the river—and in its south fork a last ditch against extinction for fall chinook: a captive brood facility, run by the Stillaguamish Tribe. Here, salmon are raised in tiny hotels hung on a wall, one salmon to each water-filled plastic box. As they grow, the fish progress to living together in large circular tanks. The biggest adults circled endlessly in their tank, kept in half light. Just like the captive brood of winter chinook I had observed in California, they will never know the sea.

Facilities like these are expensive—and a sign of desperation. In both cases, the captive brood facilities are being used to preserve the genes of a run of chinook down to just a few thousand fish.

Tribal Chairman Shawn Yanity isn’t happy his tribe can no longer fish for this population of chinook in the Stillaguamish. He is saddened that turkey and ham are on tribal tables, even for important ceremonies: fish for the first salmon ceremony is purchased from neighboring tribes.

It’s not supposed to be like this; it never was like this. But where once there was an ancient alliance between people and salmon, Yanity said, today people are in a contest with salmon for the last of what’s left. What’s at stake is identity, culture, and abundance not found in any store. Yanity wants his people fishing again.

“It’s the teachings, the stories the elders tell, the protocol and preparation for fishing and hunting,” Yanity said. The captive brood is both necessary and crushing. “I don’t want to see my culture in a tank.” This attachment to salmon isn’t only a Native American thing. In Washington, salmon are still a secular sacrament, what many people of all creeds and races say are big part of what makes Washington home. Talk to sport fishermen or old duffers living back along the deep holes of the Skagit River, hoping for a slab-sided chinook to put in the smoker. Even people who don’t fish just like to know the salmon are still here. It’s what these fish stand for: a still-functioning natural environment, the Pacific Northwest a lot of people mean when they say they live here—a place not just like everywhere else.

That’s both good and bad news for Jeff Davis, director of conservation for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. He knows people here still care about salmon. But he is also well aware he is losing this battle. A congressional tour of suburbs south of the state capital in Olympia, where pavement is pressing deeper into the remaining bastions for salmon, left him in despair. Restoration work is underway all over the state, but it is being outpaced by habitat loss. He urges a new understanding of how we use land and water that lives up to what we say we love and money to fix what we have already wrecked.

“We haven’t gone far enough,” said Ron Warren, the director of fish programs for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. I had called him and other fish managers to ask them to take stock of where we stand. “We have a no net loss of habitat policy, and that doesn’t seem to be working,” Warren said. “We have to somehow change that paradigm; there has to be a gain. We have to assure ourselves we are going to get something for the continued creep into habitat that lessens the likelihood we will ever get fish. Otherwise we will never have the cool, clean water that fish need. You have to start telling people what you think and be truthful.

“I am not knocking the choices society has made, but we have to challenge ourselves and decide, do we keep doing that? And if we don’t, how do we pay for that? How do we get four million more people here, and where is the planning for that—the new treatment plants, the runoff from the roads and that many cars? These are the things we need to look at.”

The southern resident orcas still seek the fish returning to Puget Sound rivers, surging even all the way into the urban waters offshore of downtown Seattle, hunting chum, coho, and chinook. The special time for Seattle-area residents is when the southern residents, in their final seasonal rounds of the year, come here at last. Downtown orcas. Who else has that?

Sometimes the southern residents are here for days on end, thrilling ferry riders crisscrossing central Puget Sound and people flocking to beaches all over West Seattle and Vashon and Maury Islands to watch orcas blow and breach, right offshore. One day in November 2018, J, K, and L pods were all here at once. Dozens of orcas were cartwheeling and spy-hopping, right past the Superfund site of the Asarco Smelter at Ruston near Tacoma, right past the dense-packed housing along the long-ago logged-off hillsides. They sculled underwater upside down, their bellies glowing white through the green water, and slapped their pectoral fins and flukes seemingly just for fun or maybe simply to hear the loud, resonant, smacking sound.

As the sunset painted the water gold, people thronged the beaches and shorelines, enchanted all over again at what it means to live here, in a place still alive with salmon and orcas on the hunt. The southern resident orcas that roam the region’s urban waters are like black-and-white-robed judges of a truth-and-reconciliation commission. They remind us all of what is still here and what is at risk—what we took for ourselves, what we took from them. Their hunger is an indictment, because we caused it. Their hunger points to what’s missing. At stake as the region gets richer is whether it also will get poorer, with only the grandmother orcas remembering the salmon that used to be.

Excerpted from Orca: Shared Waters, Shared Home by Lynda V. Mapes (June 2021) with permission from the publisher, Braided River (an imprint of Mountaineers Books). All rights reserved. Learn more at orca-story.com.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Lynda Mapes is a reporter for the Seattle Times and author of Orca: Shared Home, Shared Waters. She’s based in Seattle, Washington.