Pandemic Unveils Growing Suicide Crisis For Communities Of Color

17:03 minutes

This story is a collaboration between Science Friday and KHN. Read and listen to the story by KHN’s national correspondent Aneri Pattani.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

Rafiah Maxie has been a licensed clinical social worker in the Chicago area for a decade. Throughout that time, she’d viewed suicide as a problem most prevalent among middle-aged white men.

Until May 27, 2020.

That day, Maxie’s 19-year-old son, Jamal Clay—who loved playing the trumpet and participating in theater, who would help her unload groceries from the car and raise funds for the March of the Dimes—killed himself in their garage.

“Now I cannot blink without seeing my son hanging,” said Maxie, who is Black.

Clay’s death, along with the suicides of more than 100 other Black residents in Illinois last year, has led locals to call for new prevention efforts focused on Black communities. In 2020, during the pandemic’s first year, suicides among white residents decreased compared with previous years, while they increased among Black residents, according to state data.

But this is not a local problem. Nor is it limited to the pandemic.

Interviews with a dozen suicide researchers, data collected from states across the country and a review of decades of research revealed that suicide is a growing crisis for communities of color—one that plagued them well before the pandemic and has only been exacerbated since.

Overall suicide rates in the U.S. decreased in 2019 and 2020. National and local studies attribute the trend to a drop among white Americans, who make up the majority of suicide deaths. Meanwhile, rates for Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans—though lower than their white peers—continued to climb in many states. (Suicide rates have been consistently high for Native Americans.)

“COVID created more transparency regarding what we already knew was happening,” said Sonyia Richardson, a licensed clinical social worker who focuses on serving people of color and an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, where she researches suicide. When you put the suicide rates of all communities in one bucket, “that bucket says it’s getting better and what we’re doing is working,” she said. “But that’s not the case for communities of color.”

Although the suicide rate is highest among middle-aged white men, young people of color are emerging as particularly at risk.

Research shows Black kids younger than 13 die by suicide at nearly twice the rate of white kids and, over time, their suicide rates have grown even as rates have decreased for white children. Among teenagers and young adults, suicide deaths have increased more than 45% for Black Americans and about 40% for Asian Americans in the seven years ending in 2019. Other concerning trends in suicide attempts date to the ’90s.

“We’re losing generations,” said Sean Joe, a national expert on Black suicide and a professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “We have to pay attention now because if you’re out of the first decade of life and think life is not worth pursuing, that’s a signal to say something is going really wrong.”

These statistics also refute traditional ideas that suicide doesn’t happen in certain ethnic or minority populations because they’re “protected” and “resilient” or the “model minority,” said Kiara Alvarez, a researcher and psychologist at Massachusetts General Hospital who focuses on suicide among Hispanic and immigrant populations.

Although these groups may have had low suicide rates historically, that’s changing, she said.

Paul Chin lost his 17-year-old brother, Chris, to suicide in 2009. A poem Chris wrote in high school about his heritage has left Chin, eight years his senior, wondering if his brother struggled to feel accepted in the U.S., despite being born and raised in New York.

Growing up, Asian Americans weren’t represented in lessons at school or in pop culture, said Chin, now 37. Even in clinical research on suicide as well as other health topics, kids like Chris are underrepresented, with less than 1% of federal research funding focused on Asian Americans.

“It’s important to continue to share these stories.”

It wasn’t until the pandemic, and the concurrent rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans, that Chin saw national attention on the community’s mental health. He hopes the interest is not short-lived.

Suicide is the leading cause of death for Asian Americans ages 15 to 24, yet “that doesn’t get enough attention,” Chin said. “It’s important to continue to share these stories.”

Kathy Williams, who is Black, has been on a similar mission since her 15-year-old son, Torian Graves, died by suicide in 1996. People didn’t talk about suicide in the Black community then, she said. So she started raising the topic at her church in Durham, North Carolina, and in local schools. She wanted Black families to know the warning signs and society at large to recognize the seriousness of the problem.

The pandemic may have highlighted this, Williams said, but “it has always happened. Always.”

Pinpointing the root causes of rising suicide within communities of color has proven difficult. How much stems from mental illness? How much from socioeconomic changes like job losses or social isolation? Now, COVID may offer some clues.

Recent decades have been marked by growing economic instability, a widening racial wealth gap and more public attention on police killings of unarmed Black and brown people, said Michael Lindsey, executive director of the New York University McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research.

With social media, youths face racism on more fronts than their parents did, said Leslie Adams, an assistant professor in the department of mental health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“It’s not just a problem within the person, but societal issues that need to be addressed.”

Each of these factors has been shown to affect suicide risk. For example, experiencing racism and sexism together is linked to a threefold increase in suicidal thoughts for Asian American women, said Brian Keum, an assistant professor at UCLA, based on preliminary research findings.

COVID-19 intensified these hardships among communities of color, with disproportionate numbers of lost loved ones, lost jobs and lost housing. The murder of George Floyd prompted widespread racial unrest, and Asian Americans saw an increase in hate crimes.

At the same time, studies in Connecticut and Maryland found that suicide rates rose within these populations and dropped for their white counterparts.

“It’s not just a problem within the person, but societal issues that need to be addressed,” said Shari Jager-Hyman, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania’s school of medicine.

In Texas, COVID-19 hit Hispanics especially hard. As of July 2021, they accounted for 45% of all COVID deaths and disproportionately lost jobs. Individuals living in the U.S. without authorization were generally not eligible for unemployment benefits or federal stimulus checks.

During this time, suicide deaths among Hispanic Texans climbed from 847 deaths in 2019 to 962 deaths in 2020, according to preliminary state data. Suicide deaths rose for Black Texans and residents classified as “other” races or ethnicities, but decreased for white Texans.

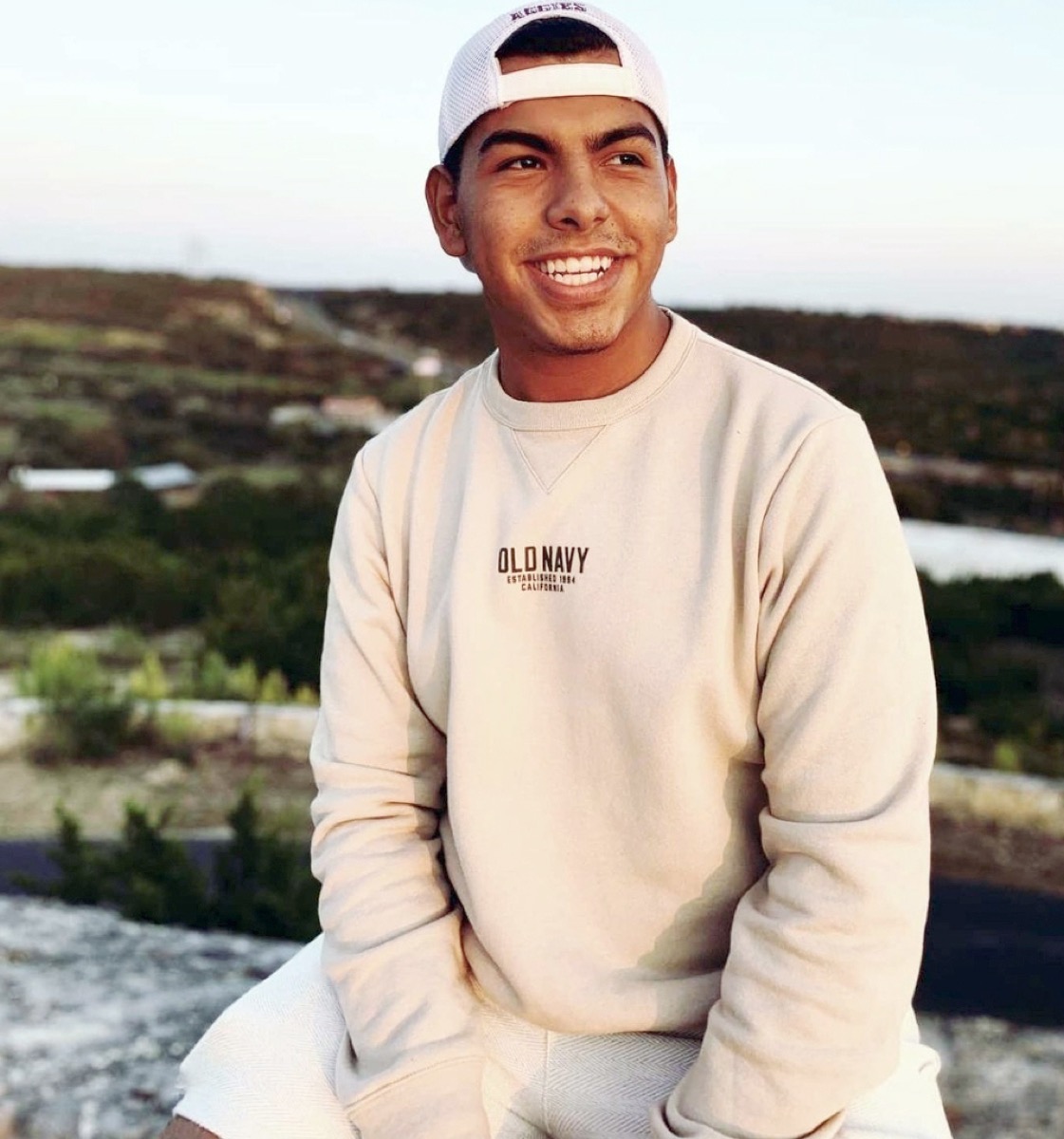

The numbers didn’t surprise Marc Mendiola. The 20-year-old grew up in a majority-Hispanic community on the south side of San Antonio. Even before the pandemic, he often heard classmates say they were suicidal. Many faced dire finances at home, sometimes living without electricity, food or water. Those who sought mental health treatment often found services prohibitively expensive or inaccessible because they weren’t offered in Spanish.

“These are conditions the community has always been in,” Mendiola said. “But with the pandemic, it’s even worse.”

Four years ago, Mendiola and his classmates at South San High School began advocating for mental health services. In late 2019, just months before covid struck, their vision became reality. Six community agencies partnered to offer free services to students and their families across three school districts.

Richard Davidson, chief operating officer of Family Service, one of the groups in the collaborative, said the number of students discussing economic stressors has been on the rise since April 2020. More than 90% of the students who received services in the first half of 2021 were Hispanic, and nearly 10% reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm, program data shows. None died by suicide.

“These are conditions the community has always been in. But with the pandemic, it’s even worse.”

Many students are so worried about what’s for dinner the next day that they’re not able to see a future beyond that, Davidson said. That’s when suicide can feel like a viable option.

“One of the things we do is help them see … that despite this situation now, you can create a vision for your future,” Davidson said.

Researchers say the promise of a good future is often overlooked in suicide prevention, perhaps because achieving it is so challenging. It requires economic and social growth and breaking systemic barriers.

Tevis Simon works to address all those fronts. As a child in West Baltimore, Simon, who is Black, faced poverty and trauma. As an adult, she attempted suicide three times. But now she shares her story with youths across the city to inspire them to overcome challenges. She also talks to politicians, law enforcement agencies and public policy officials about their responsibilities.

“We can’t not talk about race,” said Simon, 43. “We can’t not talk about systematic oppression. We cannot not talk about these conditions that affect our mental well-being and our feeling and desire to live.”

For Jamal Clay in Illinois, the systemic barriers started early. Before his suicide last year, he had tried to harm himself when he was 12 and the victim of bullies. At that time, he was hospitalized for a few days and told to follow up with outpatient therapy, said his mother, Maxie.

But it was difficult to find therapists who accepted Medicaid, she said. When Maxie finally found one, there was a 60-day wait. Other therapists canceled appointments, she said.

“So we worked on our own,” Maxie said, relying on church and community. Her son seemed to improve. “We thought we closed that chapter in our lives.”

But when the pandemic hit, everything got worse, she said. Clay came home from college and worked at an Amazon warehouse. On drives to and from work, he was frequently pulled over by police. He stopped wearing hats so officers would consider him less intimidating, Maxie said.

“He felt uncomfortable being out in the street,” she said.

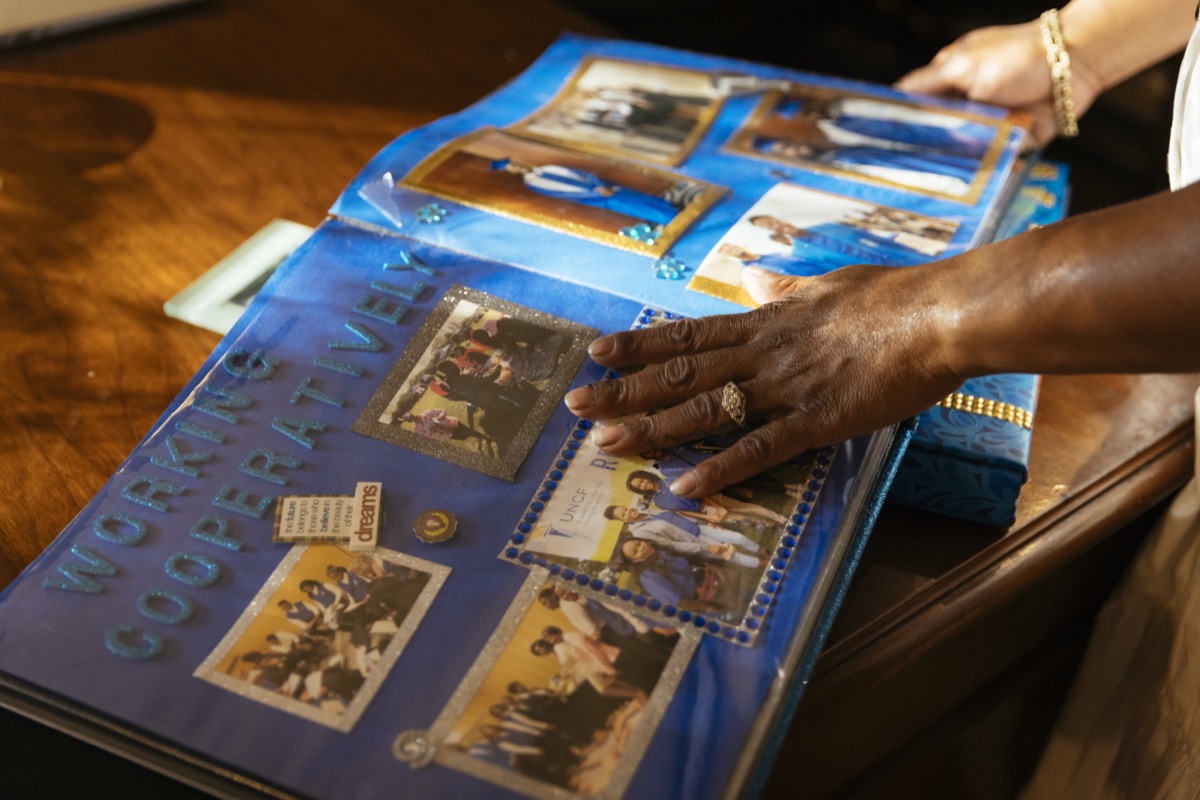

Maxie is still trying to make sense of what happened the day Clay died. But she’s found meaning in starting a nonprofit called Soul Survivors of Chicago. Through the organization, she provides education, scholarships and shoes—including Jamal’s old ones—to those impacted by violence, suicide and trauma.

“My son won’t be able to have a first interview in [those] shoes. He won’t be able to have a nice jump shot or go to church or even meet his wife,” Maxie said.

But she hopes his shoes will carry someone else to a good future.

KHN senior correspondent JoNel Aleccia contributed to this report.

[Editor’s note: For the purposes of this story, “people of color” or “communities of color” refers to any racial or ethnic populations whose members do not identify as white, including those who are multiracial. Hispanics can be of any race or combination of races.]

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Aneri Pattani is a national correspondent with Kaiser Health News in Raleigh, North Carolina.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. A heads up that our next story is about suicide, and it may be distressing to some listeners. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a lot of cracks in American life. Things like pay disparities, housing, and job security, racism. A lot of these realities became a lot more dire, though, over the last year and a half.

And alongside this, another crisis has been bubbling up– suicide rates in communities of color are rising, especially in Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations. Experts say it’s not a coincidence that the pandemic has exposed this issue, but the suicide rates were increasing before COVID-19. So how does the country tackle this problem?

This crisis is COVID in a new report by my guest. Aneri Pattani covers mental health and substance use for Kaiser Health News. She’s based in Raleigh, North Carolina. And Aneri, welcome to Science Friday. Thanks so much for joining us.

ANERI PATTANI: Thanks for having me.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Let’s talk first about these statistics that we have for this rise in suicides in communities of color. How much of a rise are we talking about, and how long has this been going on?

ANERI PATTANI: Nationally, there’s data from the CDC that shows that there’s been a steady increase in suicide deaths among communities of color since the early to mid 2010s. So there’s this study by the National Institute of Mental Health that found between 2014 and 2019, the suicide rate increased 30% for Black individuals, and 16% for Asian or Pacific Islander individuals.

And when you drill down into specific age groups, that data goes back further, and is more concerning. So for Black teens, from 2001 to 2017 the suicide rate increased 60% for boys, and 182% for girls. And what’s particularly notable is that the rates continue rising for communities of color even when they fall for white Americans.

So in 2019, the National Suicide rate dropped for the first time in more than a decade. And this was a big deal. But when you drill down into that data, the drop was driven by a decrease in suicides among white Americans, while the rates kept going up for communities of color. And it seems like the same might be true during 2020, the first year of the pandemic.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And these age demographics hold true, as well. These numbers often skew younger than suicides among white people.

ANERI PATTANI: Yeah, so for Communities of Color, the age group that’s at highest risk for suicide over most of these years has been adolescents and young adults. And in some cases for Black Americans, there’s even research showing that suicide rates among kids younger than 13 are going up, too. Versus for white Americans, your highest risk group tends to be middle age and older adults.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So for many years, as you’ve said, suicide rates have been highest among white, middle aged men. Is this something that is changing?

ANERI PATTANI: Not exactly. So here we get into the nuances, a little bit, of how we look at the data. So if we’re talking about in any single year, who has the highest number of suicide deaths or highest suicide rate per capita, that is still going to be middle aged white American men. However, if you look at trends over time, you see that suicides are increasing among young people of color faster. And even in the years that the suicide rate drops for white Americans, they continue increasing for people of color.

So when I’m talking to researchers, certainly they say more needs to be done to address the suicide rate among white Americans. But they’re also concerned about this initial increasing trend, and they want to draw attention to communities of color and suicide before we wait for that rate to get up to where it is for white Americans.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Let’s talk a bit about the possible reasons for why this crisis is happening right now in communities of color. In reporting the story, what are some common threads that you found?

ANERI PATTANI: Let me start off by saying that suicide is a complex issue, and there’s not one single factor that causes it. And it’s also really hard to study, because the person who could answer the question as to why is not there. Still, there are some trends that researchers mentioned to me. So over the last decade, there’s been a lot of economic instability, and there’s tons of research that links loss of jobs or lack of job prospects to suicide risk.

There’s also been a widening in the racial wealth gap. So we’re talking about disproportionately affecting communities of color with poverty, with unsafe housing conditions, all of these risk factors also linked to suicide. And then there’s also been more public attention on police killings of Black and Brown people. And there have been many studies out there that show that affects not just the mental health of the people who know the individual who died, or was shot, but the community at large. And so these factors coming together can lead to hopelessness and increased suicide risk.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So just to clarify, is there a way to determine the reasons for this rise in suicides, or is this just really speculation for now?

ANERI PATTANI: So there are studies that can be done where researchers would interview the family and friends of people who died by suicide, and try to really pinpoint for each case what pieces may have come together that led to the death. But those studies are expensive, and they’re really time consuming, so they’re not done that often. I know some are being done to look at the suicide deaths in 2020 during the pandemic, but obviously, we don’t have those results yet.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, speaking of that, your story does note that this trend was happening before the pandemic. Maybe we can talk a bit more about that. Are some of the reasons the same pre-pandemic and now?

ANERI PATTANI: So researchers are still looking into that, but there definitely seems to be some overlap. During the pandemic, researchers saw disparities in suicide by race and thought, what are the factors that could be at play here? There’s the fact that communities of color were disproportionately affected by COVID. They lost loved ones, which causes a lot of grief. They lost jobs, lost housing, face food insecurity, all of which could have contributed to that increased suicide rate.

But a lot of these factors were also disproportionately affected communities of color before the pandemic. And so they are thinking it could have been those same factors that were affecting the rising rate, beforehand, too. But really, they need a lot more research to figure out if that’s the case, for sure.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So it’s really important to point out here that your story is not about the COVID pandemic causing this rise in suicide amongst people of color.

ANERI PATTANI: Absolutely. So this is something that has been going on– some studies will look at it since the 90s. Definitive national data shows it from the mid 2010s. So this is another one of those things where this was already happening, and COVID just put a spotlight on the fact that it was existing.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to hear the voices of some of the people that you talk to. And one of the threads that you were pulling in your reporting is people saying to you, we just really don’t talk about that. We don’t talk about suicide. And I have a clip here from Cathy Williams, a mom from Durham, North Carolina, who you talked to for your story. Her son Torian died by suicide in 1996, and she told you that she didn’t know what signs to look for. She only learned afterwards when she looked for Information about suicide.

CATHY WILLIAMS: And that was when, when the presenter was going over the signs and symptoms of depression and suicide, I started checking them off. I said, oh, my goodness. I saw that. Saw that. Oh, I saw that. I saw that. And I said, that was Torian.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It seems as though she’s talking about suicide, but not talking a lot about the underlying mental health issues. Maybe you can talk a bit more about Cathy and what she’s trying to do for her community.

ANERI PATTANI: So after Cathy lost her son, Torian, she really channeled that pain into a mission. So her mission now is to not let any other parents miss those warning signs because they don’t know what to look for. So after her son passed, she listened to these presentations, took mental health trainings, went to conferences, did research, and really wanted to bring that learning back to her community.

So she started presenting at her son’s high school at her church in Durham, and telling people what are the signs to look for, in the hopes that no one else misses it. And also, in the hopes that– at the time she told me people thought suicide was a white issue. And in her community, black people didn’t talk about suicide. And she was hoping she could get that ball rolling so that no one else would be in the situation that she was in.

JOHN DANKOSKY: What other resources are available in some of the communities where you were doing your reporting, though, because Cathy and people like her can only do so much.

Absolutely. So over time, a lot of groups have actually sprung up to bring awareness and education on this issue. So there’s the National Organization for People of Color Against Suicide. And this was actually started by a woman named Donna Barnes, who’s Black. And she lost her son to suicide in 1990, so around the same time as Cathy.

There’s also the Acoma Project, which focuses on researching and preventing suicide and depression, specifically in youth of color. And at the college level, there’s the Steve Fund, which is dedicated to mental health concerns for University Students of Color. And of course, there are a ton more in local areas, but those are some of the ones that I came across in my reporting.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to turn to talking specifically about the Asian-American community, right now. Asian-American young adults are the only racial group where suicide is the leading cause of death. Do we know why this is?

ANERI PATTANI: Such an important question, and unfortunately, the short answer is no. We don’t know why this is. Despite the fact that the suicide rate is rising among this group, and it’s really high for adolescents, there is shockingly little data and research on Asian-Americans. Actually, less than 1% of federal research funding goes to any health research, including suicide, focused on that group. So the little that we do suggests that maybe the model minority myth, this idea that Asian-Americans are smart, and successful, and don’t need help, could impede people from seeking care.

But in reality we need to learn a lot more. Actually, one of the researchers I spoke with compared it to– we used to think that Black Americans are not impacted by suicide, she told me. But then we started funding research into that area, and we looked at the data broken apart, and we saw that, actually, suicide among Black youth is increasing at a really alarming rate. So what might we find if we actually fund that research into Asian-American youth?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Now, you just said there’s not very much data on this group. Is there any information on how Asian-American suicide rates have changed at all during the pandemic?

ANERI PATTANI: So right now, the CDC has not released national data for 2020 broken down by race. So we don’t know, at a national level, what’s happening. What my colleague and I did is we did reach out to individual states and asked for their preliminary data on suicides by race and ethnicity. And again, not all of them have it, or will share it. But some did, and it suggests that in certain states, there is an uptick in suicide deaths among Asian-Americans, as well as other communities of color.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Yeah, and that’s a really important note. All states don’t keep this data the same way. If they do, it’s very hard to parse this out at a national level.

ANERI PATTANI: Yeah, absolutely. My colleague and I reached out to all 50 states and the territories, and less than half got back to us with that information.

JOHN DANKOSKY: As we talk about the strategies and the different resources that people could use, did you find that different resources were needed depending on the community, or that the same strategies really do work for everybody?

ANERI PATTANI: So I spoke with maybe a dozen or so suicide researchers for this story, and pretty much all of them agreed, across the board, that the resources need to be tailored to the community that you’re trying to reach. And that doesn’t mean they have to be drastically different, but the idea is to take something like cognitive behavioral therapy, that works in one community, and just make some small changes so that it’s relevant and appropriate for the people you want to use it with.

So actually, one of the people I spoke with was Sonya Richardson. She’s a social worker in North Carolina who works with People of Color, and she researches suicide. I think this clip from her explains it pretty well.

SONYIA RICHARDSON: If I want to culturally adapt an intervention for Black youth, then I’m going to meet with Black youth in their community, and their family, and perhaps and stakeholders. Hear from them, OK, how can we take this model and make it work for you? What do we need to do differently? Who needs to be at the table? When we say that it’s and your family, who is the family? Is that the aunts? Is it the grandmother? Are those the other people that we need at the table, and not just your parents?

And so it’s really getting the collective voice of the community, and the people that are targeted by the intervention, getting their input in it and then culturally adapting that intervention to where it works for that population.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s Sonyia Richardson, a social worker in North Carolina. She works with people of color and researches suicide. We’re talking with Aneri Pattani. She’s a reporter for Kaiser Health News who’s just written a big report about this issue. I’m John Dankosky and this is Science Friday, from WNYC Studios.

Aneri, a few years back, we heard a lot about depths of despair here in the US. Deaths from suicide, drug overdoses, alcohol, that were really tied to economics. Do you see some similarities between that crisis and this one in communities of color?

ANERI PATTANI: Yes, this parallel was actually brought up by a lot of the researchers and the families that I spoke with. I think we’re starting to realize that suicide is not just driven by psychiatric or mental illness factors. It has a lot to do with our environments– with economic opportunities, systemic barriers, things that make communities feel hopeless about their future. And that’s sort of the conversation we had with Depths of Despair a few years ago, which largely focused on white rural Americans. But a lot of those same factors apply in the conversation you and I are currently having about Communities of Color.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to play another clip here from Kiara Alvarez. She’s a researcher and psychologist at Mass General Hospital. She studies suicides among Hispanic and immigrant populations, and she wants to see a shift in how we think of responsibility and suicide.

KIARA ALVAREZ: Mental health providers are doing incredible work during COVID, but we can’t have the assumption that increased mental health need just means more reliance on mental health providers. That can’t be the only thing that we do. Infusing mental health support, and infusing social support, are the economic support, the structural support, that families need to thrive is going to be critical to supporting the mental health of entire communities.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Aneri, as someone who covers this issue so closely, I’m wondering what you take away from what you just said. Do you think that some of the systems that she talking about here will be in place in the future?

ANERI PATTANI: I don’t know if it will happen, or those systems will be in place, because when we’re talking about systemic solutions, that means a lot of moving factors, a lot of people, organizations that have to get on board. But it certainly seems like there’s evidence to suggest that we should consider moving that direction.

So much research on the rise in suicide rate for communities of color points to these issues like economics, housing, systemic racism, and those just can’t be addressed in one on one therapy. Of course, mental health services are important, but like Kiara points out, there are a lot of other things that we could do that could be affecting the suicide rate at a population level.

JOHN DANKOSKY: What else are you following closely in terms of mental health in America right now, as this COVID pandemic continues?

ANERI PATTANI: So I’m certainly interested in the National Suicide data by race one that comes out from the CDC, later this year, to see, on a national level, are we seeing those disparities continue through 2020? I’m also paying attention, I think like a lot of people, to children, adolescents, and college students. These groups that were already at high risk in a lot of cases, and have dealt with a lot of upheaval over the past year, how are they doing, and what are the long term consequences there?

And I think largely, I’m curious to see if the pandemic shifts how we talk about some of these mental health issues, suicide. Is it enough to highlight these disparities that existed before the pandemic, but is it enough to get attention on them now to do something? Is it enough to motivate us to think about systemic solutions to suicide, and not just mental health services as a silo? I’m not sure if it will be, but I’m really interested to see.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Aneri Pattani covers mental health and substance use for Kaiser Health News. She’s based in Raleigh, North Carolina. Thanks so much for joining us. I really appreciate it.

ANERI PATTANI: Thanks for the conversation.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Kaiser Health News, KHN, and Science Friday have partnered to bring you this story. You can read Aneri’s full report at and sciencefriday.com. And if you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Or you can text home, that’s H-O-M-E, to the crisis text line at 741-741.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Kyle Marian Viterbo is a community manager at Science Friday. She loves sharing hilarious stories about human evolution, hidden museum collections, and the many ways Indiana Jones is a terrible archaeologist.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.