Where Did Watermelon Come From?

06:41 minutes

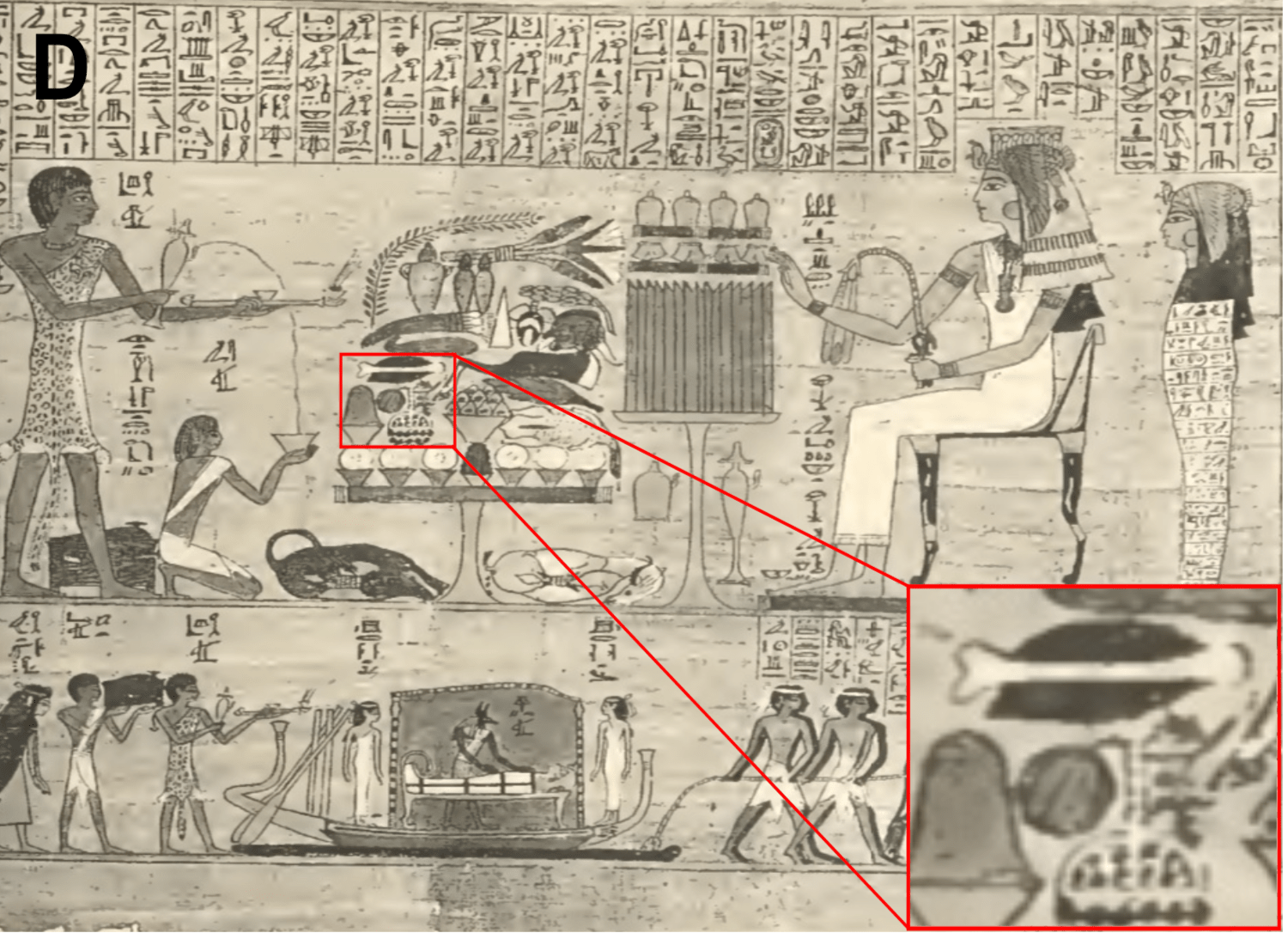

You may think of watermelon as a red, sweet taste of summer. The watermelon itself is ancient—paintings have been found in Egyptian tombs depicting a large green-striped object resembling a watermelon next to grapes and other sweet, refreshing foods. But if you look at many of the melon’s biological cousins, its red, sweet pulp is nowhere to be found—most close relatives of the watermelon have white, often bitter flesh. So how did the modern watermelon become a favorite summer snack?

Back in the 1960s, Russian researchers suggested that one sweeter melon species found in south Sudan might have been a close relative of the modern watermelon. Now, a detailed genetic analysis of a handful of wild melon species, and 400 modern varieties of watermelon from around the world, has concluded that the Kordofan melon from Sudan is, in fact, the closest living relative of the watermelon.

Susanne Renner, an emeritus professor at the University of Munich and an honorary professor of biology at Washington University in St Louis, explains the work on the origins of the modern melon—and how knowing the history of the watermelon could lead to new varieties.

Susanne Renner is an emeritus professor at the University of Munich and an honorary professor of Biology at Washington University in St Louis.

IRA FLATOW: Perhaps no food says summer better than a chilled slice of juicy watermelon. And now, researchers have been piecing together genetics, history, and Egyptian tomb art to slice into the question of just how the modern watermelon came to be. Charles Bergquist has more.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: You know the watermelon as a red, sweet taste of summer. But many of its melon relatives have whitish pulp, and they’re often bitter. Back in the 1960s, Russian researchers suggested that a sweet melon from South Sudan may have been a close watermelon relation. And now, an international team of researchers has analyzed the DNA of over 400 watermelon varieties from around the world. And they’ve concluded that Kordofan melon from the Sudan may indeed be the closest link to the modern watermelon.

Susanne Renner is an emeritus professor at the University of Munich and an honorary professor of biology at Washington University in St. Louis. She’s one of the authors of a paper on the work, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. I asked her just how far back what we think of as a watermelon has existed.

SUSANNE RENNER: It depends on what you define as the watermelon, because there are so many forms of watermelon. In West Africa, people like to snack on the seeds. They don’t eat the pulp. They form with the red, sweet flesh as we know it today, super sweet and perhaps even without seeds, is a product of the past 50 to 100 years of intensive breeding. But people certainly enjoyed watermelon pulp I think or we think, based on our research, by 4,000, 5,000 years ago.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Walk me through how you know about that. Part of it relies on art found in Egyptian tombs?

SUSANNE RENNER: Yes. The tomb art, by itself, a painting of three fruits in different tombs that certainly look like watermelons to us doesn’t prove that there pulp was eaten raw. It could have been bitter things and people were, as I said, eating the seeds. So the painting, as such, is not sufficient. Although in context with other evidence, you say, oh, yes, this food is depicted on a tray next to grapes and other refreshing vegetables, lotus flowers that were also eaten, and snake melons. But it’s not enough. The painting alone doesn’t do it.

But knowing from our really solid sampling of all kinds of watermelons that exist in Africa– we think there are six or seven wild species– so we have high quality genomic data of well understood representatives of each wild species. And they all have bitter fruits that have white pulp. And then we have the genomes of 400 types of domesticated watermelons from China, from [INAUDIBLE]. And in this context, in this large sampling of genetic data, the Kordofan melon, which is represented only by genomes from three plants, comes out as closer to the domestic watermelon than anybody else.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: If you were going to start with something like a Kordofan and selectively breed it into what we know as a modern watermelon, how long would that take you?

SUSANNE RENNER: Yes, so it’s an annual crop. Every year, you get a new generation, in principle. It’s very hard to say. With modern, conscious breeding, you get changes fairly fast. But this modern level breeding, where you understand that there are genetic traits that you want to enhance in the offspring and you need to do self-pollination and things like that, that is a recent thing. The modern breeding, as I said, in watermelons, it’s well documented, started about 1900, precisely 1907. The word “gene” was coined in 1905. Mendel’s Laws were rediscovered in 1900. This is all so recent.

So how long it took ancient farmers to get desired traits– let’s say sweetness or red colored– is very hard to know. I would think hundreds of years.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Is there a specific gene for redness or juiciness?

SUSANNE RENNER: Yes. The redness, the red color has been much researched in red fruits. The genes underlying the red color are well understood. And as you probably know, red is good for you. So lycopenes and carotenoids are potent antioxidants. It’s good to eat red watermelons or red tomatoes. So that is well understood. And one can look, if one has high quality data from ancient material– 100-year-old, 200-year-old quantity or material– and who have the relevant part of the genome well sequenced, you can see the mutations that cause the presence of red or absence of red.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So does knowing the origins of the watermelon get you any closer to being able to improve the modern watermelon?

SUSANNE RENNER: I think so. Currently, for the past 100 years, breeding better watermelons has focused on bringing in genes from South African material. Now, they will have to focus on Sudanese or southern Egyptian populations. They will be closer. They will have other types of alleles having to do with, let’s say, mildew resistance or drought resistance, because these watermelons are growing in the desert. And really, they are drought resistant.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: What would you like to know next? What’s the cutting edge of watermelon for you?

SUSANNE RENNER: OK, it’s getting the ancient genome. So I can say this, this is a manuscripts we are literally working on right now. High level genomic data from seeds that are 6,000 years old or 4,000 years old. And then you can see if the red color or the sweetness, or loss of bitterness rather, was there when it came. That’s the next step. Ancient DNA.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Interesting. Susanne Renner is an emeritus professor at the University of Munich and an honorary professor of biology at Washington University in St. Louis. Thank you so much for taking time to talk about this with me today.

SUSANNE RENNER: Thank you, Charles.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: For Science Friday, I’m Charles Bergquist.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.