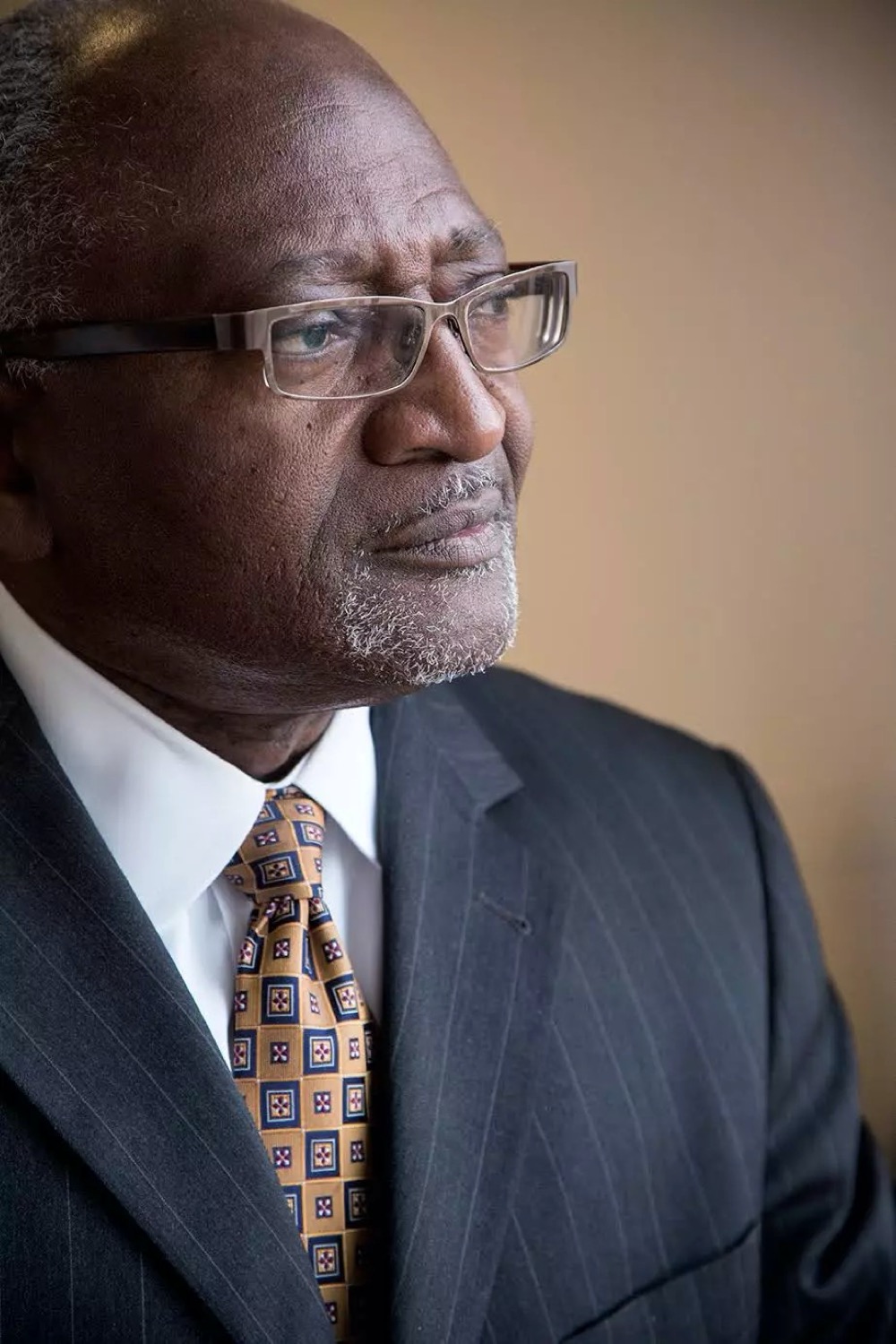

10 Questions With The Father Of Environmental Justice

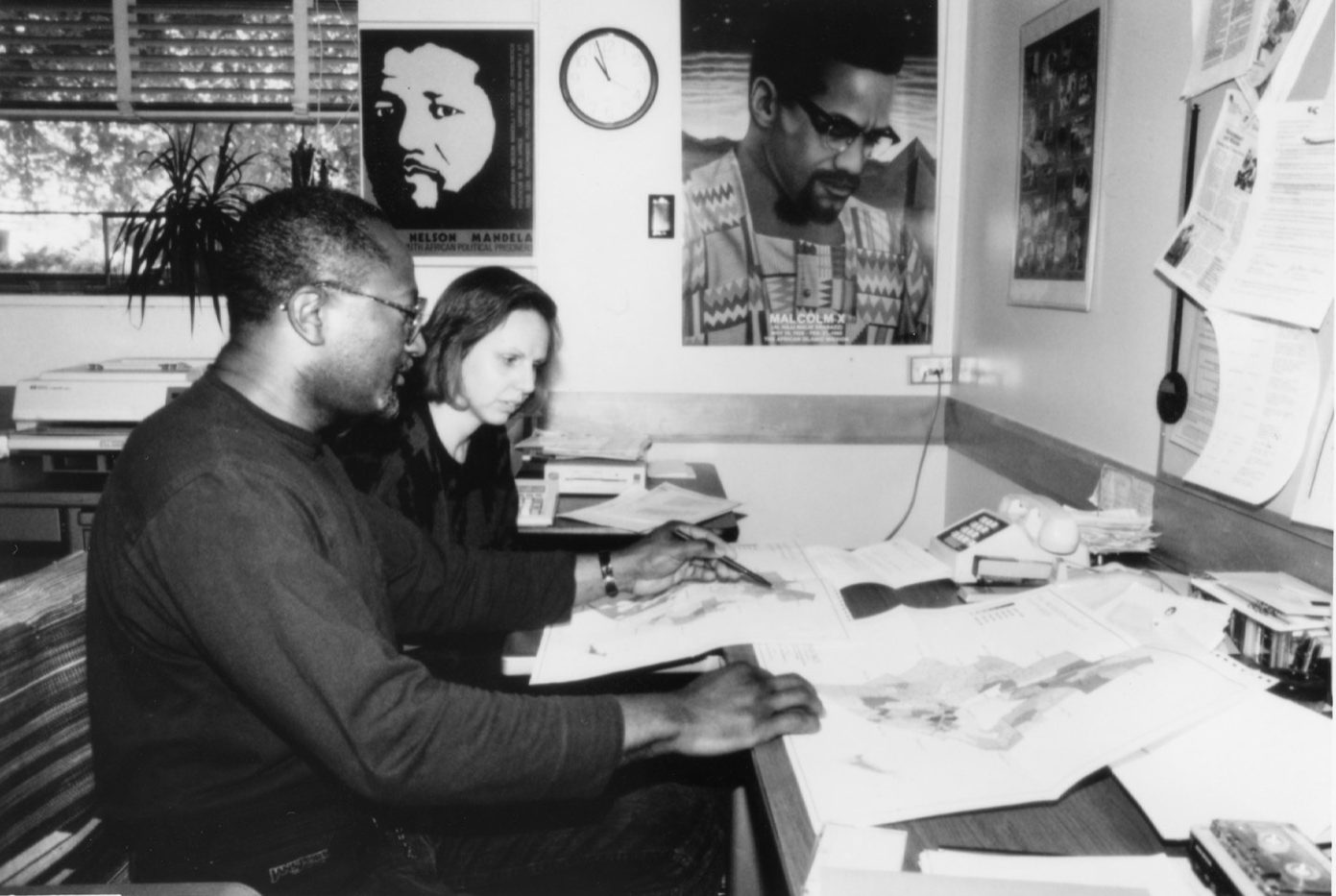

Since 1979, Robert Bullard has studied the disproportionate impacts of pollution on communities of color. He reflects on the past and future of the environmental justice movement.

One day in 1979, Robert Bullard came home to learn about a lawsuit that would set him on a research path for the next 42 years. His wife, attorney Linda McKeever Bullard, told him about a case she was working on, representing Black residents in Houston, Texas who were fighting against the placement of a landfill in their neighborhood. The residents felt that their community, and other Black communities in the city, was being targeted by waste management companies. No demographic studies on the location of waste management sites in Houston had been done before, and Bullard, then assistant sociology professor at Texas Southern University, was pulled in to collect the data.

Bullard’s study revealed an alarming trend: From the 1920s to 1978, more than 80% of Houston’s household garbage landfills and incinerators were located in mostly Black neighborhoods. At the time, Black people made up only 25% of the city’s population. Regardless of class and income, “it didn’t matter how much money you make,” Bullard says. “If you were a Black person in Houston, your community was basically targeted for all the landfills.”

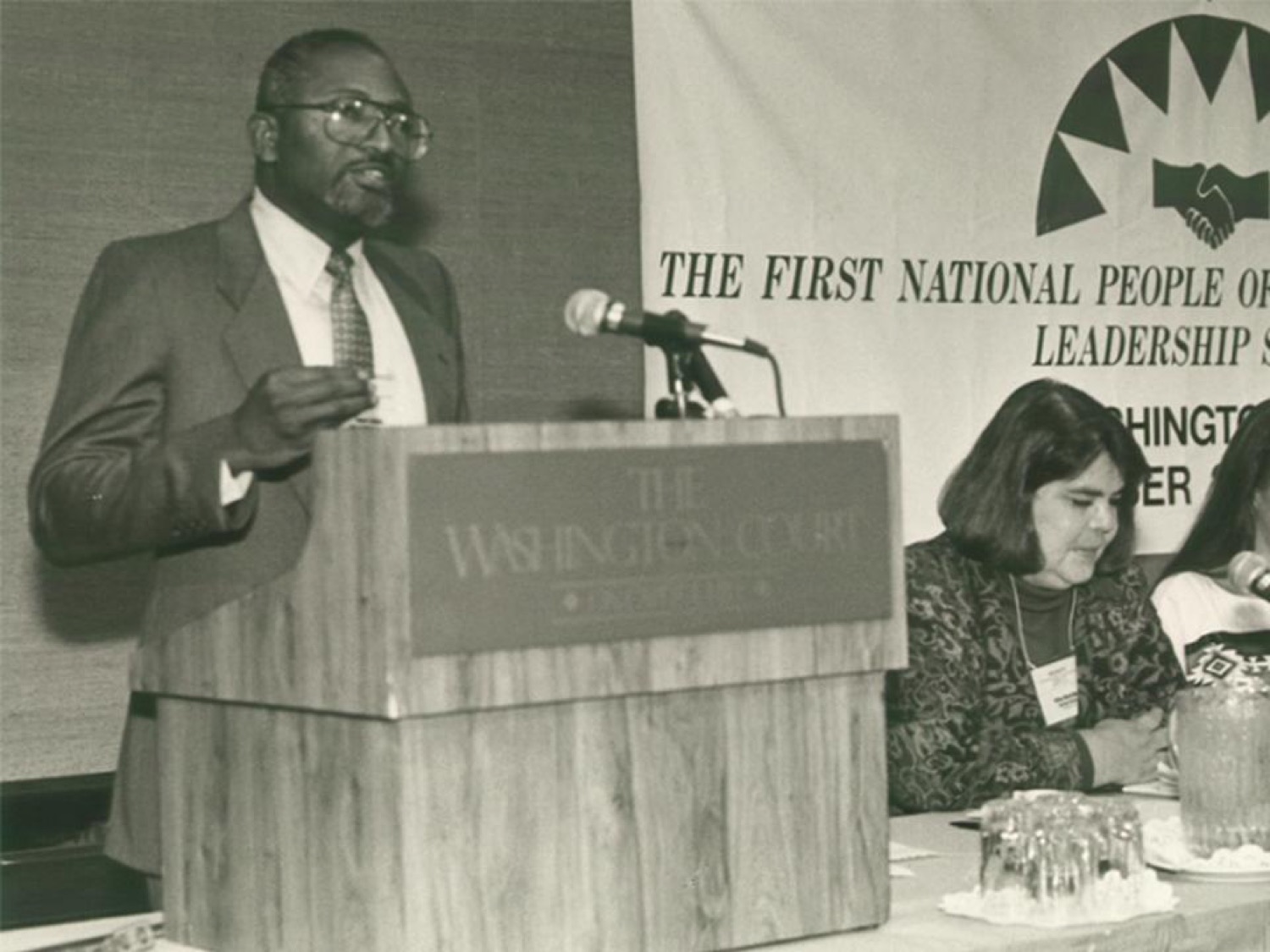

The 1979 lawsuit, Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation, was the first to challenge environmental racism using Civil Rights law. While the residents lost and the landfill was built in the neighborhood, the case and Bullard’s comprehensive study set the stage for the environmental justice movement—a cause demanding that all people have equal protection from environmental laws. Bullard, now a distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, has become a leading figure in environmental justice. Over the years, he has written pivotal studies and books, including Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality. Many refer to him as the “Father of Environmental Justice.”

“It fell in my lap,” Bullard tells Science Friday. “It was not something that I planned on doing for the next 40 years, but it just happened.”

In recent years, environmental justice has gained momentum, growing from an often dismissed movement of 1970s American activism to being the mission of today’s school clubs and youth climate groups. In March 2021, the White House launched an Environmental Justice Advisory Board. Bullard is one of the members, along with 26 leaders in environmental justice.

“In 1979, environmental racism, environmental justice, was basically a footnote. But then you fast forward 40 plus years later, it’s a headline now,” he says.

For Earth Day, Science Friday caught up with the Father of Environmental Justice to ask about his early days in the movement, his research on landmark cases, his excitement to work with youth climate leaders, and his outlook on current and future challenges in environmental policy and racial justice.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

How did you get started in the field of environmental justice and racism?

I was drafted to do the study [for the Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation]. It fell in my lap. It was not something that I planned on doing for the next 40 years, but it just happened. And the more I learned, the more I studied, the more I wanted to know more. From then, I started gathering research, data, doing studies, writing books, and trying to really provide as much information to communities and to the general public, and hopefully, it would trickle up to government to make policy.

“In 1979, environmental racism, environmental justice, was basically a footnote. But then you fast forward 40 plus years later, it’s a headline now.”

How did you get the title, “Father of Environmental Justice?”

Well as far back as that 1979 study in Houston, people started saying, “Well, you’re the father.” When we did this study in ‘79, there was nothing out there to even try to pattern the study or replicate the study. So it was just such a novel area.

In 1979, environmental racism, environmental justice, was basically a footnote. But then you fast forward 40 plus years later, it’s a headline now. That’s the change.

Listen to more archival soundbites and learn about the history of the environmental movement in Science Friday Rewind.

You were a guest on Science Friday in 1992 for a discussion about environmental injustices. In that conversation, you said: “In 1979, there were very few people out there talking about environmental discrimination, environmental racism, and I was one of those persons, and people would look at me as if I was crazy, as if somehow I was looking for discrimination under every rock.” What was going on at the time?

It was really incredible, just baffling. When I discovered the research in Houston in 1979, five out of five of the city-owned landfills, six out of eight of the city-owned incinerators, three out of four the privately owned landfills, were in Black neighborhoods. More than 80% of all the garbage dumped in Houston in the ‘20s up to 1978 were dumped in Black neighborhoods, even though Blacks made up only 25% of the population. You’re 25% of the population, but you get 80% to 82% of all the garbage dumped on you. Something was wrong with that.

I took those findings to a number of environmental groups and the response was, “Well, isn’t that where the garbage is supposed to go? Gotta go somewhere.” I even took it to the oldest Civil Rights organization, same data, and I got back, “Well, we don’t work on that. We don’t work on environment. We work on discrimination in voting, education, employment.”

When I was trying to get a publisher for Dumping in Dixie, I finished the book around 1989, and I got nasty letters from publishers. I showed them the data, but big publishing houses were saying: “You can’t say that there’s an environmental injustice, everybody is treated the same, the environment impacts everybody the same. So how can you say that there’s such a thing as environmental racism? You just can’t see it.”

“When we talk about climate change, we don’t have 40 years to get it right. The urgency of now is what’s pushing this intergenerational movement.”

Earth Day 2021 is just around the corner. April 22, 1970 marked the first Earth Day and launched the modern environmental movement in the U.S. How did environmental justice fit in at the time?

Let’s not be revisionist historians. The first Earth Day was about the environment, seen through the eyes of white middle class. White organizations had very little to do with issues around vulnerability, issues around marginalization, issues around race and justice. Now, in all fairness, it was at the same time that much of the energy of the Civil Rights movement was focused on addressing racism. The Civil Rights movement was not heavily involved in environmentalism. Although, we have to remember that Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968 went to Memphis, Tennessee on an environmental justice issue of striking sanitation workers. He was killed before he could finish that mission.

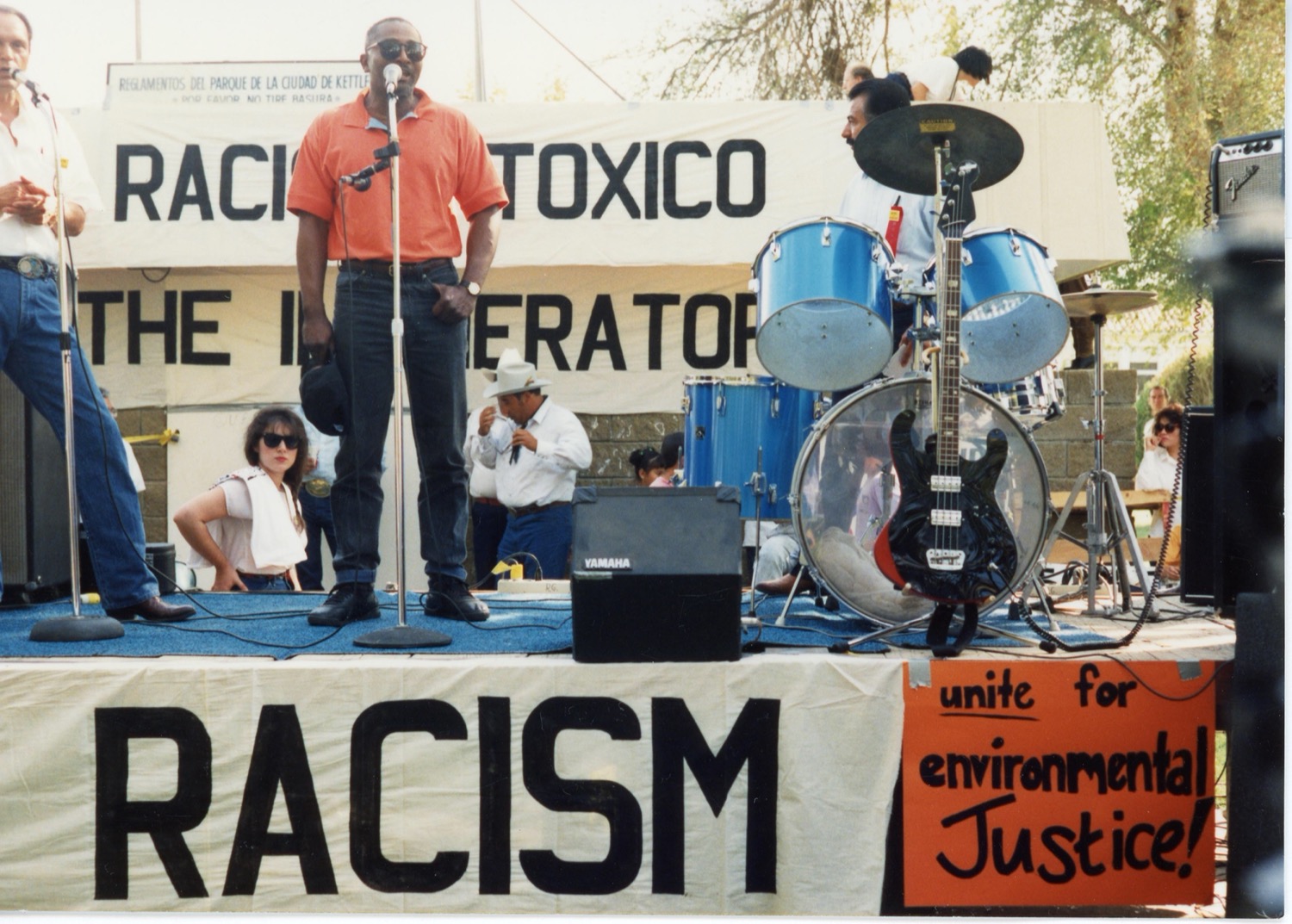

But it took a while before people in the environmental movement and Civil Rights movement saw the issues as one of the same. The Bean v. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation was nine years after the first Earth Day. When that case was filed, we could not get any white environmental groups to help us nor could we get any civil rights groups to help us. Then in 1985, the Bean case went to trial and we lost the case. But in terms of the movement, [the case] energized a lot of us to keep going forward. In addition, in 1982, the protests in Warren County, North Carolina against the toxic PCB dump site in African American communities thrust the environmental justice movement into the world. Black people were saying, “No, we aren’t going to stand for being dumped on.”

As you mentioned, the environmental and conservation movement has a history of being led by predominantly white people and organizations. How has that impacted environmental justice?

All kinds of reports have been written about the whiteness of environmental groups and I tell people that those groups will always be white groups, because that’s the way they were founded. I’m not preoccupied with that. What I’m preoccupied with is diversifying the green dollars that flow disproportionately to those organizations and the extent to which they talk about sharing. I want to know if they talk about changing policies, changing strategies and funding streams, assisting and supporting people of color organizations and frontline community organizations. That doesn’t mean that white organizations should not diversify their boards and staff. But if they just stopped at just diversifying the staff and not the money, our community will still be starved for resources.

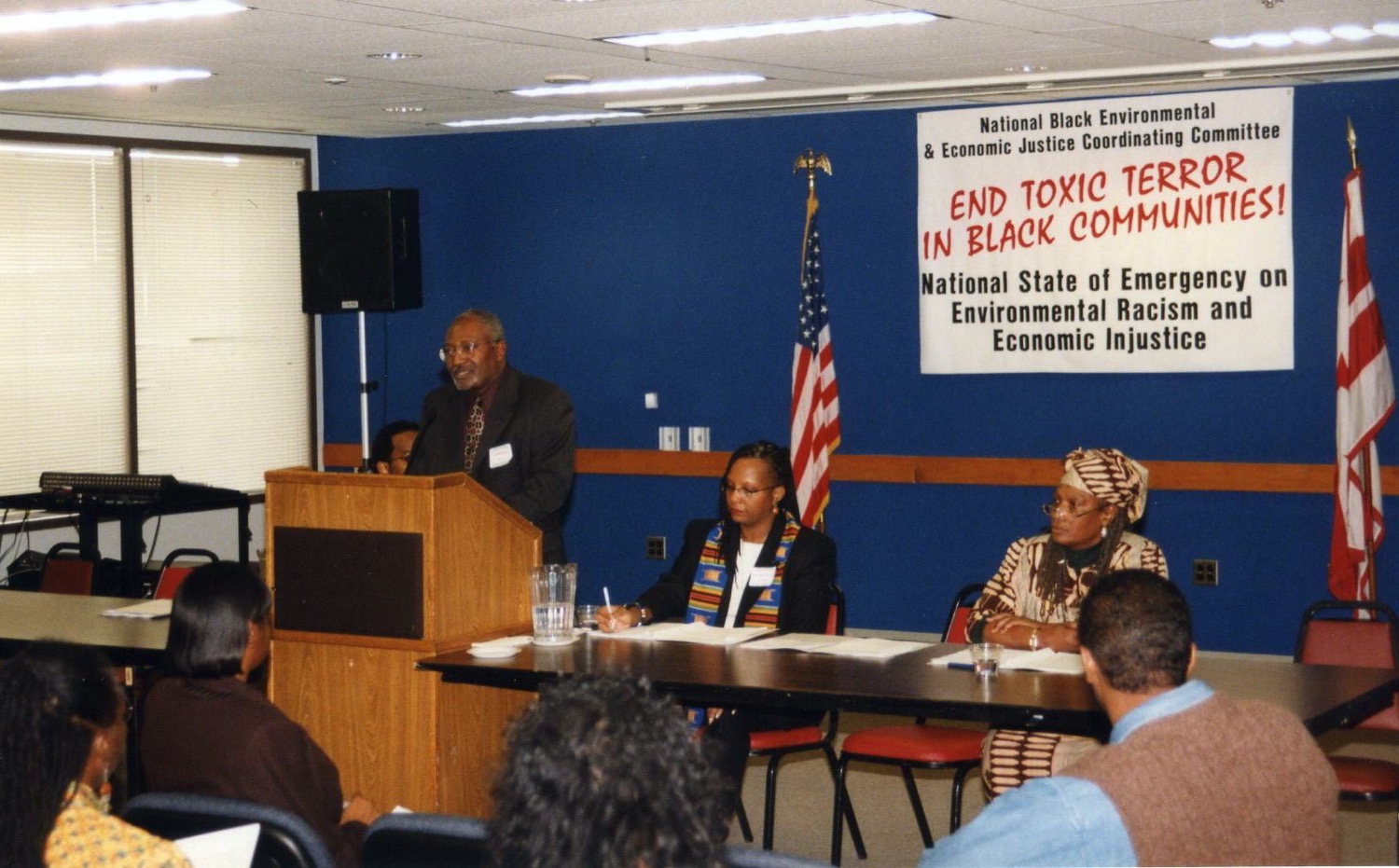

You’ve worked extensively with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU). What’s their role in bringing awareness to environmental inequities?

It makes me feel good to see the important role that our historically Black college university played in really bringing up the issue of environmental racism and environmental justice. They connected the dots and had professors and students push it out. We really saw our Black colleges and universities take on these issues when no universities would take on this issue. As they were creating environmental justice groups on their campuses, other organizations and people started reaching out to work with them.

Now we have an EPA administrator who graduated from North Carolina A&T State University, a HBCU in Greensboro, North Carolina. And we have a vice president, first African American, Asian descent, who is a graduate of Howard University. Both of them are champions for environmental justice and racial justice. The changes that are occurring today are built on a solid foundation HBCUs helped paved.

“The fight today is about justice.”

You mentioned that now environmental justice is “headline” news. How does that feel? Where is environmental justice today?

We have been waiting for this magic moment. Communities of color will tell you, I’m talking 30-40 years ago, that this is all connected. They’ll tell you about the fact that their neighborhood floods, the fact that they don’t have grocery stores, the fact that there are no parks, and the fact that all these polluting facilities are in their neighborhoods. All the jobs are in their area, but they don’t get the jobs, they get the pollution. They get sick and some of them die. And the policies, as they rolled out, only deal with one one aspect of the issue. But today it’s being connected across the board—a convergence of various aspects of these once very disparate movements. I think that’s a recipe for transformative change. That’s what we need today.

Today, people talk about criminal justice reform, talking about “I can’t breathe” in terms of policing. But we also talk about “I can’t breathe” when it comes to these industries that have been poisoning people. Even right now, people of color are more likely to suffer from the impacts of bad air, because we live in, unfortunately, those geographic locations where air quality is compromised. Now, we’re facing climate change. We continue to face problems with poor communities, communities of color being disproportionately affected by climate change.

The last four decades, we’ve made progress but they’ve been baby steps. We need big footsteps. When we talk about climate change, we don’t have 40 years to get it right. The urgency of now is what’s pushing this intergenerational movement.

Tell me more about this intergenerational movement. How has environmental justice connected with students and youth climate activists?

I think that it’s important to acknowledge the need for the flow of power to the next generation. I’m a teacher. I love teaching and I tell my students this is a race to the finish, but it’s not a sprint. It’s more like a marathon relay. You run your 26.2 miles and then you pass the baton to the next generation to run the next 26.2 miles. No generation has been able to do everything. And that means that you do as much as you can, then you work with the next generation to build on and extend. That’s what’s happening right now.

That scares a lot of people. It scares a lot of people who want to maintain the status quo, and the status quo will not fly with this younger generation.

I think that the intergenerational push for justice is not just environmental justice and climate justice, but for racial justice, criminal justice, economic justice, gender justice, health justice, food and water justice—you start naming all the justice movements. It’s coming together. The fight today is about justice.

“These are exciting times. They are exceptional times and they’re challenging times. But I think there are lots of opportunities to move the needle and to make those transformative changes that are needed.”

You’re now a part of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Board, announced in March. Tell me about the board and what you are looking forward to as a member.

Historically, you get appointed to advisory boards and then you fly to Washington on your own dime, put yourself up in a hotel on your own dime. This meant that the participation was skewed toward organizations and people with money. The pandemic basically leveled the playing field. You don’t need a budget to participate; all you need is a cell phone, tablet, or computer, and Zoom. Now, we have more people of color, more representatives of frontline communities, more young people. I think the youngest one is 18.

When you look at the policies that are getting rolled out under the Biden administration, you can see the fingerprints of the justice and equity framework applied across the board. For example, we [the board] recently laid out a work plan looking at the Justice40 initiative, which is President Biden’s plan to move to a green energy economy, and direct 40% of the generated funds and revenues toward frontline communities, underserved communities, and communities that have been economically disenfranchised or have been left behind for decades. That’s historic.

This is exciting. This is seeing environmental justice and climate justice elevated to the highest level. It’s elevating it to the White House, and making sure that all of the agencies see through a justice lens. It’s all hands on deck. All government agencies will need to begin to look at climate and look at justice issues. Where there’s energy, transportation, or when we look at health—all of it we see as tied together. The equity part is bringing all the pieces together.

Any final reflections on the future of environmental justice?

Seeing the work expanding and the movement mature from small, often isolated and invisible communities, to today’s organization at the White House, makes me feel good.

I’m excited. These are exciting times. They are exceptional times and they’re challenging times. But I think there are lots of opportunities to move the needle and to make those transformative changes that are needed. That makes me hopeful and optimistic, and makes me want to keep working and be part of it.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.