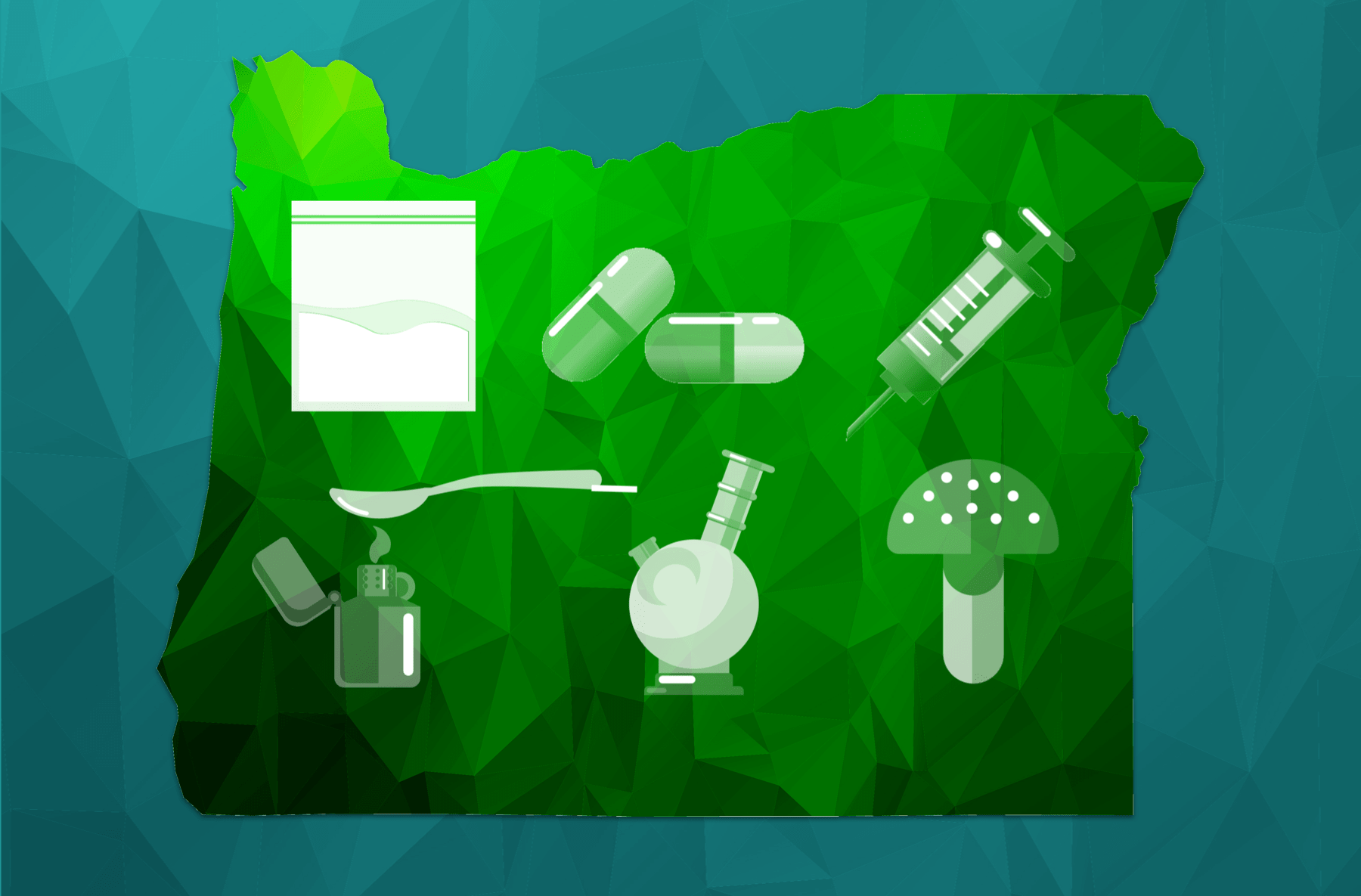

Oregon Just Decriminalized Small Amounts of All Drugs. Now What?

13:37 minutes

On February 1, a big experiment began in Oregon: The state has decriminalized small amounts of all drugs, including heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. In the November election, voters passed ballot Measure 110 by a 16-point margin.

Now, if you’re caught with one or two grams of what some refer to as “hard drugs”, you won’t be charged. Instead, you’ll either pay a maximum $100 dollar fine, or complete a health assessment within 45 days at an addiction recovery center. This new system for services will be funded through the state’s marijuana tax.

But the measure is still controversial, and members of Oregon’s addiction and recovery community are split on if it’s a good idea. So how did we get here?

Oregon has a long history of progressive health-related measures, says reporter Tatiana Parafiniuk-Talesnick. She reports on things like COVID-19, poverty and Measure 110 for the Register-Guard newspaper in Eugene.

“There’s just a strong legacy of counter-culture culture here,” she says. “I think most people familiar with some of the bigger cities here know that.”

Oregon became the first state to decriminalize marijuana use in 1973. Eugene, the third-largest city in the state, deploys healthcare workers, not police, when someone is having a mental health crisis. And it was the first state to enact a Death with Dignity Act in 1997, which allows terminally-ill people to end their lives on their terms, using lethal medications.

Measure 110 was spearheaded by the Drug Policy Alliance, a New York-based organization focused on reducing criminalization associated with drug use across the country. Kassandra Frederique, executive director of the DPA, says the organization has worked in Oregon for more than two decades.

“We have worked with folks on medical marijuana, on adult use, and we’ve supported folks on the ground there for a very long time,” she says. “And Oregon also has urban centers and rural centers and super rural centers, so there’s a lot of diversity.”

This means how well decriminalization works in Oregon could reflect how well it works across the country, too.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

In Oregon, as in the rest of the country, there’s racial disparity in who gets written up for drug possession. Before Measure 110, if you were Black or Native in Oregon, you were a lot more likely to get in trouble for possession of a controlled substance. However, Oregon already reduced the possession of small amounts of drugs from a felony to a misdemeanor, so not a lot of people were spending time in jail just for possession.

Andy Seaman, an assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University and Healthcare for the Homeless Clinician at Central City Concern in Portland, says successful care for people with addiction is all about transparency and empathy.

“I will not judge you for your substance use,” he says. “Addiction can be a relapsing and remitting disease. It’s ok if you use again, please just come back.”

Seaman used to be a doctor in the Multnomah County Jail in Portland. He says he often saw a cycle with patients who had to go cold turkey in jail: They go through withdrawal in an unfamiliar environment, they’re traumatized, and when they’re released, they seek out drugs to self-medicate. Overdose risk for opioid users is 129 times higher in the first two weeks of someone being released from jail.

“Certainly there are scenarios where people have gone to jail, and that was a wake up call,” Seaman says. “A lot of people in Oregon Recovers are those people. But these are the people who survived.”

Measure 110 requires the establishment of a statewide network of addiction recovery centers. The problem is these centers haven’t been established yet, and they don’t legally have to be until October. Temporarily, there’s a phone line where people can call to do their assessment on the phone. If you don’t want to do that, you pay a fine.

Those who work in addiction recovery services in Oregon are split: There are people who are really excited about Measure 110, and those who are wary.

Mike Marshall was one of the loudest voices against Measure 110. He is executive director of Oregon Recovers, an organization that serves and advocates for people in recovery for addiction. He’s in recovery himself, for alcohol and crystal meth.

Marshall supports decriminalization, but he says Oregon’s recovery services system is fractured and incomplete. People often have to wait several weeks for a treatment bed, and many service centers are outside of the traditional healthcare system.

“There’s nothing in 110 that prepares the healthcare system, or expands capacity,” he says. “They simply deconstructed one system,” the pathway through treatment through the criminal justice system, “without recognizing the healthcare system isn’t prepared for them.”

Marshall says that previously when people got arrested or written up for possession, many were court-mandated treatment. The system wasn’t perfect, but it helped some people get into recovery. Now, Marshall says a lot of people will be cut off from that support because small level possession will now be treated as essentially a speeding ticket.

“I think the largest unintended consequence is that the overdose rates are going to shoot up,” Marshall says. “There’s going to be more people on the street using drugs, and no mechanisms to either interrupt that or direct them out of that.”

Haven Wheelock runs a health services program for drug users in Portland called Outside In. She works with people in the community who are often homeless, and primarily inject heroin and meth. Outside In runs one of the oldest syringe access programs in the country.

Wheelock was one of the chief petitioners for Measure 110, and is thrilled the measure passed.

“When people tell me they’ve spent the last five years constantly scared, constantly looking over their shoulder because of their substance-use disorder, and they tell me they feel like they can breathe a little bit? That’s a win—just decriminalizing simple possession is a huge win,” she says.

She says Mike Marshall is right, that treatment systems are not quite prepared for Measure 110. But Wheelock thinks doing anything is better than nothing.

“We do have more work to do—we are really going to need to continue to build out this system. The system has been left in disrepair,” she says. “I’m really hopeful for what this means for our community and for our state. And if we can show that this is working, hopefully Oregon being brave will lead other places to be brave too.”

Tera Hurst, executive director of the Oregon Health Justice Recovery Alliance, says this is only the beginning for bringing service to Oregonians.

“The Oregon Health Justice Recovery Alliance is actively engaged with the legislature to ensure that the low-barrier, culturally responsive treatment and recovery services promised to Oregonians through the measure are swiftly and adequately funded,” Hurst said. “The additional funding outlined in the measure, which will be distributed as grants to community organizations throughout the state, will greatly expand access to services that have been historically fractured and underfunded.”

According to Kassandra Frederique of the Drug Policy Alliance, the organization is campaigning in many other states to replicate Oregon’s ballot measure, including in Washington, Colorado, California, and Virginia.

“This is the same thing we did years ago, where we had conversations with a bunch of folks and said, ‘Who’s ready?’” she said. “We plan to do this again and again and again.”

Editor’s Note 3/5/21: This story was updated to add comment from the Oregon Health Justice Recovery Alliance.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Haven Wheelock is Drug Services Coordinator for Outside In in Portland, Oregon.

Kassandra Frederique is Executive Director of the Drug Policy Alliance in New York, New York.

Mike Marshall is Executive Director of Oregon Recovers in Portland, Oregon.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. There’s an experiment going on in Oregon. Last month a measure went into effect that decriminalizes small amounts of all drugs. Needless to say, this is a big deal.

NEWS ANCHOR 1: Oregon voters have cast their ballots in favor of Measure 110.

NEWS ANCHOR 2: This is getting headlines around the country.

NEWS ANCHOR 3: In Oregon, voters chose to decriminalize small amounts of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine– also mushrooms–

NEWS ANCHOR 4: It’s the first state in the country to have a rollback like this. Possession of common street drugs will go from a misdemeanor to a citation. And on that citation will be a number to call for recovery help.

IRA FLATOW: Oregon, like many other places in the country, is dealing with an addiction crisis. And the people behind this measure know that. It’s an effort to treat addiction like a health care issue instead of a criminal justice one. But Oregon’s addiction and recovery community is split on whether this experiment is a good idea. Syfy producer, Kathleen Davis, takes a closer look.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Haven Wheelock runs a health services program for drug users in Portland, Oregon. It’s called Outside In.

She works with people in the community who are often homeless and primarily inject heroin and meth. It runs one of the oldest syringe access programs in the country.

HAVEN WHEELOCK: I am working to promote health and healing and hope with people who are using substances, regardless of where they are on the continuum of change. If they want to change their behavior, then great. Let’s help do that. If they don’t want to change their behavior, that’s fine, too.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Haven has been feeling pretty optimistic about the people she works with lately. That’s because on February 1, a measure went into effect that decriminalized the possession of small amounts of all drugs in Oregon. That means if you’re caught with one or two grams of a drug like heroin or meth, you won’t be charged. Instead you’ll either pay a maximum $100 fine or complete a health assessment within 45 days at an addiction recovery center.

HAVEN WHEELOCK: When people tell me that they’ve spent the last five years constantly scared, constantly looking over their shoulder, constantly feeling vilified because of their substance-use disorder, and they tell me that they feel like they can breathe a little bit, that’s a win. Just decriminalizing simple possession is a huge win for folks.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Haven was one of the chief petitioners behind Measure 110, meaning she was out there getting signatures to get it on the ballot. In November, Oregonians voted to approve it by a 16 point margin. It’s the first state in the country to approve decriminalization at this scale. But wait. A lot of you are probably wondering how we got here. We’ve been conditioned to think drugs are capital B bad. Remember those commercials, your brain’s going to fry like an egg?

So why decriminalize them? Drugs, for half a century, have been treated as a criminal justice issue. When that started, it was kind of an experiment itself.

What we know as the War On Drugs here in the US started during the ’70s during the Nixon administration, right after the Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s. Nixon framed Civil Rights as contributing to an increase in crime and targeted drugs as a way to crack down.

Heroin, meth, and marijuana were all made Schedule 1, which means they have no medical benefits and high potential for abuse, according to the government. But it wasn’t based in a lot of science. Here’s Katharine Neill Harris, a fellow in drug policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute in Houston.

KATHARINE NEILL HARRIS: And so that’s when the whole idea of this law-and-order politics really took root. And being tough on drugs is an extension of being tough on crime. It allowed Nixon and other Republicans to kind of capitalize on this racial animus and appeal to white voters, and also turn public attention away from other problems that the country was facing, both at home and abroad.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So for decades, this tough-on-crime attitude towards drugs remained. Drug use did go down, according to the federal government, but the War On Drugs also decimated neighborhoods– very frequently Black, Latino, and other minority communities. But things started to change in the ’90s, according to Katharine.

KATHARINE NEILL HARRIS: The War On Drugs is really expensive. And states need balanced budgets. So they were like, we need to do something to reduce incarceration, if we can. They were very limited, but there were some sorts of rollbacks that you started to see.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: In 1996, California became the first state to legalize medical marijuana. Over the next two decades, 34 states followed suit. And 16 states have voted to legalize recreational marijuana. But weed is not the same as heroin or meth, so why was Oregon willing to take a risk with decriminalizing small amounts of what so many think of as “hard drugs?”

Well Oregon has long been looked at as a progressive state for health-related measures. It was the first state to decriminalize weed possession in 1973. Eugene, the third-largest city in the state, deploys health care workers, not police, when someone is having a mental health crisis.

And Oregon was the first state to enact a Death With Dignity Act in 1997. This allows terminally ill people to end their lives on their terms with lethal medications. Measure 110, the drug decriminalization measure, was spearheaded by the Drug Policy Alliance, or DPA, an organization focused on reducing criminalization associated with drug use across the country. Oregon seemed like the perfect candidate.

KASSANDRA FREDERIQUE: DPA has worked in Oregon for over two decades.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Kassandra Frederique is the Drug Policy Alliance’s Executive Director. She and the organization are based in New York.

KASSANDRA FREDERIQUE: So we have worked with folks on medical marijuana and adult use. And we’ve supported folks on the ground there for a very long time. And Oregon also has urban centers and rural centers and super-rural centers. And so there’s a lot of diversity.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: In Oregon, as it is in the rest of the country, there’s a racial disparity in who’s written up for drug possession. Before Measure 110 in Oregon, if you were Black or Native, you were a lot more likely to get in trouble for possession of a controlled substance.

KASSANDRA FREDERIQUE: Overwhelmingly, folks told us, it’s really bad. We don’t want to criminalize people.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: It’s important to note, though, that possession of small amounts was already reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor in Oregon. So not a lot of people were spending time in jail just for this. Kassandra and the other big backers behind Measure 110 say, look, throwing people in jail, giving them hefty fines, treating them as criminals for drug possession and addiction can’t be the best solution. So they say, let’s treat decriminalization as a health care issue.

Andy Seaman is an assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University. He’s also a health care clinician for the homeless in Portland. He says, successful health care for people with addiction is all about transparency and empathy.

ANDY SEAMAN: I will not judge you for your substance use. And addiction can be a relapsing and remitting disease. It’s OK if that happens. If you use again, please just come back.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Andy used to be a doctor in the Multnomah County Jail in Portland. He says he often saw a cycle with patients who had to go cold turkey in jail. They’d go through a withdrawal in an unfamiliar environment– they’re traumatized– and then when they’re released, they seek out drugs to self medicate. For opioids, overdose risk is 129 times higher in the first two weeks of someone being released from jail.

ANDY SEAMAN: Certainly there are case scenarios where people have gone to jail and then were arrested, and that was a wake up call. Or maybe they were in prison and they found their recovery that way.

A lot of people in Oregon recovery are those people. They’re people who made it through a pathway like that. But these are the people who survived.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Like so many states, Oregon is grappling with an addiction problem. In 2018 there were eight overdose deaths for every 100,000 residents. And it’s gotten worse. There was a 40% jump in overdose deaths over 2019 in the first half of 2020.

Officials in Oregon say pandemic disruptions are to blame. This problem is exacerbated because Oregon has a really poor system for getting people help for addiction.

MIKE MARSHALL: We have three to four to five week waits to find a treatment bed.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: That’s Mike Marshall, Executive Director of Oregon Recovers, an organization that serves and advocates for people in recovery for addiction. Mike is in recovery himself. He’s 13 years clean from alcohol and crystal meth. He was one of the loudest voices against Measure 110 in the recovery community.

Mike says Oregon’s recovery system is fractured and incomplete. A lot of centers were developed outside of the health care system. He calls them “mom and pop shops.” And because the system is so fractured, it can take time to get help.

MIKE MARSHALL: The problem with the absence of a statewide coordinated plan is that here in Multnomah County, which is Portland, we have one treatment bed per 1,100 population.

Now nobody knows if that’s the right metric in a state with 9 and a half percent untreated addiction rates. That should be the first question we answer but nobody knows that. Clackamas County, which is on the other side of Multnomah County– they have one treatment bed per 36,000 people.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Measure 110 requires the establishment of a statewide network of addiction recovery centers. Instead of getting in legal trouble for possession, you can either pay a fine or get a health assessment at one of these recovery centers. Sidenote– these centers will be funded by the state’s recreational marijuana tax. The problem is, these centers haven’t been established yet. And they don’t have to be until October. Temporarily, there’s a phone line where people can call to do their assessment on the phone. Or if you don’t want to do that, you pay a fine.

This service limbo is because Measure 110 was a people’s measure, meaning it got on the November ballot because the Drug Policy Alliance and their associates gathered enough signatures. But it wasn’t a push through the legislature. The state now has to adapt to it after the fact. Mike says he’s all for decriminalization.

MIKE MARSHALL: When they said, we need to make this health care system, not a criminal justice problem, they’re absolutely right,

KATHLEEN DAVIS: But he says it was irresponsible for the people who pushed the measure to do it without the resources available first.

MIKE MARSHALL: There’s nothing in 110 that prepares the health care system or expands the capacity of the health care system to do that. They simply deconstructed one system without recognizing that it’s all well and good to say they should be in the health care system, but the health care system isn’t prepared for it.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Mike says, when people got arrested or written up for possession, a lot of them got court-mandated treatment. Mike says it wasn’t perfect, but it worked for some people to get them into recovery. Now he says a lot of people are going to be cut off from that if they’re just getting a citation for possession.

MIKE MARSHALL: And I will tell you that I think the largest unintended consequence is that the overdose rates are going to shoot up. They’ve shot up under COVID, there’s going to be more people on the street using drugs, and no mechanisms to either interrupt that or direct them out of it. And so we’re going to lose more lives.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Nearly everyone I spoke to for the story was an agreement about one thing, that Measure 110 is an experiment. Something like this has never been done before in the US, but there’s a good chance it won’t be the last state to do something like this. Kassandra Frederique, of the Drug Policy Alliance, says they’re in talks with a whole bunch of states to do something like this again, including in Washington state, Colorado, California, and Virginia.

KASSANDRA FREDERIQUE: This is the same thing we did years ago, where we had conversations with a bunch of folks and said, who’s ready? What can we do?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: For those on the ground in Oregon, the next few months and years will be crucial for how they can serve vulnerable people in their communities. For Mike Marshall with Oregon Recovers, he says he’ll be working with legislators to do some retooling on Measure 110.

MIKE MARSHALL: It’s not a matter of being for or against Measure 110. 110 is law. And so now what I would like to see is that it focus exclusively on funding harm reduction and peer support services, because that’s really what the local folks who got behind it– that’s what they know and that’s what they care about. And direct the funds into clearly articulated outcomes.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Haven Wheelock, who runs the needle exchange program in Portland, says she’s hopeful but she’s not looking at this with rose-colored glasses.

HAVEN WHEELOCK: I would work myself out of a job any day. I would love to run around with a magic wand and cure everyone in substance use disorders by tapping them on the forehead. That’s not realistic. And we do have more work to do. We are going to need to continue to build out the system. The system has been left in disrepair and I’m really hopeful for what this means for our community, for our state– and hopefully we can show that this is working. Hopefully Oregon being brave will lead other places to be brave, too.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: For Science Friday, I’m Kathleen Davis.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.