Searching For Extraterrestrial Life Like ‘Sherlock Holmes’

17:09 minutes

This segment is part of the Life Beyond Earth spotlight

View Spotlight“Some scientists find my hypothesis unfashionable, outside of mainstream science, even dangerously ill conceived,” writes Avi Loeb, an astrophysicist at Harvard. “But the most egregious error we can make, I believe, is not to take this possibility seriously enough.”

So begins Loeb’s new book, Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth. Loeb is the director of the school’s Institute for Theory and Computation, and founding director of Harvard’s Black Hole Initiative, and he wants you to take the possibility of aliens seriously.

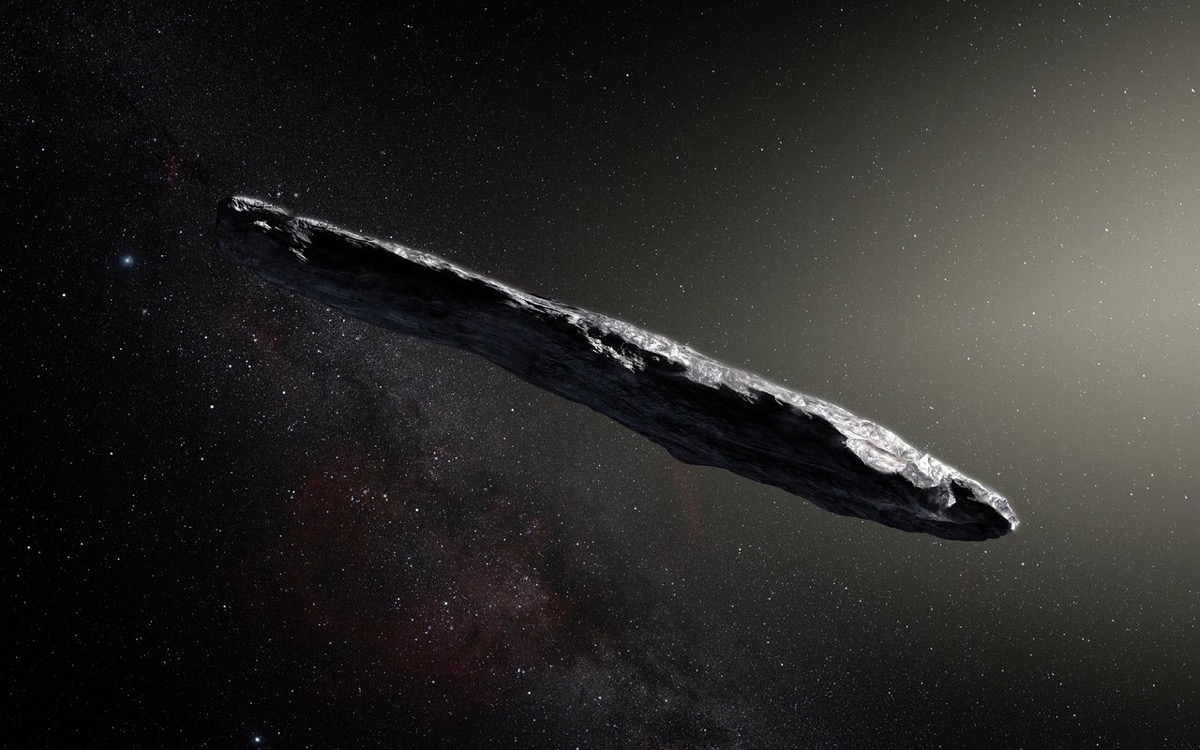

Back in October 2017, our solar system received a strange visitor, unlike any seen before. Scientists couldn’t decide if it was an asteroid, a comet, or an ice chunk. To this day, it’s simply classified as an “interstellar object,” dubbed ‘Oumuamua.’

For his part, Loeb is pretty sure what it is. It’s so hard to classify, he reasons, because it’s a byproduct of intelligent life outside our solar system. But how it found its way here is anyone’s guess.

Loeb joins Ira to talk about his theory, how an early love of philosophy shaped his views as an astrophysicist, and why searching for extraterrestrial life is a little like being Sherlock Holmes.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Avi Loeb is author of Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth and an astronomy professor at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. “Some scientists find my hypothesis unfashionable, outside of mainstream science, even dangerously ill conceived. But the most egregious error we can make I believe is not to take this possibility seriously enough.”

That’s a quote from Avi Loeb’s new book. The hypothesis that he wants you to take seriously– what is it? Well, let’s return to October 2017 when our solar system received a strange visitor unlike any seen before. Scientists couldn’t pin it down. Was it an asteroid, or a comet, or a chunk of ice, or what? To this day, it’s simply classified as an interstellar object dubbed Oumuamua.

But Loeb is pretty sure of what it is. It’s hard to classify, he reasons, because it’s a byproduct of intelligent life outside our solar system. How it found its way here is, well, we don’t know. This is the central argument of his new book Extraterrestrial, First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth. And here he is joining us to talk about it. Dr. Avi Loeb, astronomy professor at Harvard University, director of the school’s Institute for Theory and Computation, founding director of Harvard’s Black Hole Initiative. Welcome, Dr. Loeb, to Science Friday.

AVI LOEB: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Now I mentioned in my intro there that Oumuamua was a strange object which has made it hard to classify. Tell us about this object. What made it so unusual?

AVI LOEB: Yeah. The experience is similar to walking on the beach and seeing most of the time natural seashells and rocks. But every now and then you stumble across a plastic bottle that indicates that it was artificially made, that there is a civilization out there. And that’s the sense that one gets from looking at the evidence we have on Oumuamua.

It showed a lot of anomalies, the first of which was that its brightness by reflecting sunlight changed by a factor of 10 as it was tumbling over eight hours. And if you imagine a piece of paper that is razor thin tumbling in the wind, the area that is projected in front of us is not expected to change by such a large factor even for a razor thin object. So that implies that Oumuamua has an extreme geometry, an extreme shape. It is at least 10 times longer than it is wide.

And then trying to fit the light curve imply that it’s most likely flat. It’s a flat object rather than cigar shape, as was depicted in some cartoons. And then even more mysteriously, it exhibited an extra push away from the sun beyond the force of gravity that the sun exerts on it. And usually, that is provided by the rocket effect on comets when ice on their surface gets evaporated as it gets heated by sunlight.

But the only problem with that is there was no cometary tail. The Spitzer Space Telescope searched very deeply for carbon-based molecules, dust around this object, and found nothing. So there was no cometary evaporation of the object and yet it exhibited this push. In order to provide this push, about a tenth of the object, 10% of the mass of this object, had to evaporate. And we haven’t seen anything.

And so the question arose as to what gives it this extra push. And the only thing that I could think of is reflection of sunlight. And in fact, in September 2020, there was another object that showed a similar push away from the sun without any cometary tail. It was given the name 2020SO by the astronomy community. And then astronomers figured out that in 1966, this object came from the Earth.

And according to the history books, indeed there was a rocket booster that was kicked into space from a mission called the Lunar Lander Surveyor II. And so that was this object, hollow or very thin. And so it could have been pushed by sunlight. And here we have an example of an artificial object that we could infer that is [INAUDIBLE] from the extra push. And we know that it’s artificial because we produced it. The question is who produced Oumuamua.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And you know, I’m reminded of Carl Sagan’s famous quote, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Will we ever get extraordinary evidence on this one? Do we need it?

AVI LOEB: I don’t think this statement makes much sense because the word extraordinary is really dependent on the eyes of the beholder.

For some people, dark matter is extraordinary. For others, it must be there. For some people, extra dimensions are extraordinary. For the mainstream of theoretical physics, even though we have no evidence for it, it’s not extraordinary. So my point is we should be guided by evidence.

And if the evidence shows anomalies, we should try to explain them just like Sherlock Holmes tried to explain a crime scene. We should put all the possibilities on the table and then rule them out based on the evidence. But we should not have a prejudice. The Mayans, the Mayan culture, collected a lot of data on planets, the motion of planets in the sky and where they are, because they believed that you can forecast the outcome of the war based on where these planets are on the sky. They had the wrong idea.

They collected a lot of data. And it was completely useless because they haven’t really used it to derive, for example, Newton’s law of gravity. So my point is if we have a prejudice, if we have a prior idea about what the data means– we think that everything we see on the sky is rocks– we behave just like a caveman that is faced with the cell phone. And the cavemen would say, oh, the cell phone is just a shiny rock.

IRA FLATOW: And yet we have SETI, the search for extraterrestrial intelligent life, which means we must believe it’s out there or else we wouldn’t be searching for it. So why are we so surprised when we get some evidence for it?

AVI LOEB: Well, the problem is that the discussion of the search for technological signatures in space is at the periphery of astronomy right now. There is a taboo on interpreting anomalies in that way. And very little funding is allocated for such a search. And moreover, young people are discouraged from entering this field. So it’s as if you are stepping on the grass and saying, look, the grass doesn’t grow.

Obviously, we don’t have a lot of evidence because this possibility is not entertained by the mainstream. And I find that to be inappropriate because we now know from the Kepler satellite data that a substantial fraction about half of all the sun-like stars have a planet the size of the Earth roughly at the same distance from the star, implying that all these planets could have liquid water on the surface and the chemistry of life as we know it.

So if you arrange for similar circumstances, the most conservative mainstream approach would be to say you’ll get the same outcome. If you repeat the experiment, you get the same outcome. So why would we feel that we are special, unique, and that there is nothing out there? The mainstream approach would be to say, oh, there should be billions of other places where technologies may develop just like we find them on Earth. Let’s go and search.

We should be open-minded. Instead, they get a pushback on the suggestion that these technological civilizations may have left relics in space, space junk, the way we do. We launched the Voyager I, Voyager II, New Horizons that will exit the solar system. Why wouldn’t we imagine other civilizations sending messages in a bottle? And all we need to do is check our neighborhood for this space trash, so to speak.

IRA FLATOW: I’m also wondering– and you mentioned this in your book– why you– you’re a very well known and respected scientist– why you have taken it upon yourself to believe in this. And it has something to do with your upbringing with your early interest in philosophy, if I understand it correctly from your book. Please tell us about that.

AVI LOEB: Yes. I’m not the typical astronomer because I was mostly interested in philosophy at the young age. I grew up on a farm. And I used to collect eggs every afternoon, and drive a tractor to the hills, and read philosophy books because they address the most fundamental questions we have. But then circumstances brought me into astrophysics. And I ended up at Harvard, the chair of the department.

And I then realized that I’m actually married to my true love because astrophysics allows us to address philosophical questions with scientific tools. We can ask where did we come from. How did the universe start? How did life start? These are questions that are all addressed in the first chapter of the Old Testament, the Bible, meaning that they were of interest to humanity for millennia. And now we can answer these questions using science.

And we should not be worried about considering the possibility that life is elsewhere, because, to me, it reminds us of what happened in the Middle Ages. There were people arguing that the human body should not be dissected because it may have some magical power. There may be a soul inside of it.

So imagine our health benefits from the modern medicine not being realized because scientists would say we should shy away from dissecting the human body because there are all these nonsensical statements being made by the public. This is the same thing that the scientists are saying about science fiction. They say, oh, there is this literature that is not scientifically substantiated. There are these reports on unidentified flying objects. Therefore we should shy away from discussing this subject.

That makes no sense to me. And moreover, if the public is interested and the public is funding science, we scientists have an obligation to address this question with scientific tools now that we have the technologies. We have telescopes. And science is not an occupation of the elite. It’s supposed to address the interests of the public.

IRA FLATOW: You know, you also say that you fear that the scientists and laypeople are not ready to answer the more difficult question, is there intelligent life out there. They’re just not ready for it.

AVI LOEB: Right. And this unreadiness dates back centuries ago. And there is a student in the English Department at Harvard that decided because of my book, she decided that the theme of my book is exciting and therefore she wants to pursue a PhD thesis on that theme. And she invited me to the first PhD exam that she had. And one of the examiners asked her, do you know why Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake?

And she said, well, you know he was an obnoxious guy. He irritated a lot of people. And they burned him, which is true, but the professor corrected her and said, no, it was because he argued that other stars might be just like the sun and they might have a planet just like the Earth around them. And there may be life on those planets. And that was offensive to the church, because if there is life in other places, and that life sinned, then you need copies of Christ to visit those places to save the life their from their sins. And that was unacceptable so they burned the guy.

Now in retrospect, given the Kepler data that we have, we know that he was right, that, first of all, we know that there are many stars like the sun in the Milky Way and that they have many planets like the Earth. And therefore there is the possibility of life around these planets.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking with Doctor Avi Loeb, astronomy professor at Harvard University, director of the school’s Institute for Theory and Computation, author of Extraterrestrial, The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth.

Let me go to my next question. Towards the end of your book, you propose a new branch of astronomy called space archeology. What would these scientists look for, in your opinion?

AVI LOEB: Right. So if you look at us, which is the best guess we can have for other civilizations, I’m not particularly optimistic because we are making a lot of mistakes. We are fighting each other. We engage in destructive measures against each other rather than cooperating, which would be the most intelligent thing to do.

And as a result, we might not live very long. You know, we might produce technologies that will destroy us. And if that’s the case for other civilizations, they might be short lived. Once they develop technology, they might live for several centuries and that’s it. And that doesn’t mean that we cannot find evidence for them. It just means that most of them are dead when you look out.

And that opens a whole new window to space archeology because here on Earth, we had cultures that disappeared like the Mayan culture. But we can still learn about them by looking at the relics they left behind. And so the same thing can apply to space. We can search planets for industrial pollution that was left behind, civilizations that destroyed the climate on their planet. We can search for megastructures that they left behind, a swarm of satellites they left behind, and, of course, all kinds of probes that they sent out of their planetary system that we may find as space trash.

IRA FLATOW: It seems to me that you’re putting yourself in a sort of unusual position. You’re a very accomplished astrophysicist. You’re willing to fight for this theory that the object is extraterrestrial and not only extraterrestrial but made from intelligent life even if your colleagues find this idea unfathomable. Why are you willing to do this, to die on this hill, so to speak?

AVI LOEB: Well, there are two aspects to it. First, I served in the military at age 18 in Israel. And one of the sayings was that sometimes the soldier needs to put his body on the barbed wire so that others can pass forward. And then in order for younger people to be able to discuss the subject openly, I feel an obligation to insist.

And the second is that I don’t regard this as a speculation that we are not alone. In fact, I don’t think that we are the smartest kid on the block or the sharpest cookie in the jar. And the only way to find out for us to mature is to find evidence for others. And it seems completely reasonable to me to put it in the mainstream of astronomy.

I just use common sense. I don’t understand why my colleagues would disagree with that because, for example, when we search for most of the matter in the universe, the dark matter, we are searching in directions that didn’t prove to be successful. And that’s much more speculative than what I’m proposing. And I very much hope that things will turn around because I did work in the past on frontiers that were not recognized at the time when I started them. And by now, they’re very popular and part of the mainstream. And so this sense of pushback is not new to me.

IRA FLATOW: If we don’t know what 95% of the universe is made out of, what do we know about anything?

AVI LOEB: I completely agree. I think that our knowledge is an island in an ocean of ignorance. And despite what many scientists try to claim that we know so much, I think we know very little.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if you’re like Sherlock Holmes and you believe when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth, you’re going to like this new book written by Dr. Avi Loeb. Thank you, Dr. Loeb, for taking time to be with us today.

AVI LOEB: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Avi Loeb, astronomy professor at Harvard University, director of the school’s Institute for Theory and Computation, founding director of Harvard’s Black Hole Initiative, and author of a really interesting new book, Extraterrestrial, The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _abck | 1 year | This cookie is used to detect and defend when a client attempt to replay a cookie.This cookie manages the interaction with online bots and takes the appropriate actions. |

| ASP.NET_SessionId | session | Issued by Microsoft's ASP.NET Application, this cookie stores session data during a user's website visit. |

| AWSALBCORS | 7 days | This cookie is managed by Amazon Web Services and is used for load balancing. |

| bm_sz | 4 hours | This cookie is set by the provider Akamai Bot Manager. This cookie is used to manage the interaction with the online bots. It also helps in fraud preventions |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| csrftoken | past | This cookie is associated with Django web development platform for python. Used to help protect the website against Cross-Site Request Forgery attacks |

| JSESSIONID | session | The JSESSIONID cookie is used by New Relic to store a session identifier so that New Relic can monitor session counts for an application. |

| nlbi_972453 | session | A load balancing cookie set to ensure requests by a client are sent to the same origin server. |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| TiPMix | 1 hour | The TiPMix cookie is set by Azure to determine which web server the users must be directed to. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| visid_incap_972453 | 1 year | SiteLock sets this cookie to provide cloud-based website security services. |

| X-Mapping-fjhppofk | session | This cookie is used for load balancing purposes. The cookie does not store any personally identifiable data. |

| x-ms-routing-name | 1 hour | Azure sets this cookie for routing production traffic by specifying the production slot. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| bcookie | 2 years | LinkedIn sets this cookie from LinkedIn share buttons and ad tags to recognize browser ID. |

| bscookie | 2 years | LinkedIn sets this cookie to store performed actions on the website. |

| lang | session | LinkedIn sets this cookie to remember a user's language setting. |

| lidc | 1 day | LinkedIn sets the lidc cookie to facilitate data center selection. |

| S | 1 hour | Used by Yahoo to provide ads, content or analytics. |

| sp_landing | 1 day | The sp_landing is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| sp_t | 1 year | The sp_t cookie is set by Spotify to implement audio content from Spotify on the website and also registers information on user interaction related to the audio content. |

| UserMatchHistory | 1 month | LinkedIn sets this cookie for LinkedIn Ads ID syncing. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __jid | 30 minutes | Cookie used to remember the user's Disqus login credentials across websites that use Disqus. |

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookie is installed by Google Universal Analytics to restrain request rate and thus limit the collection of data on high traffic sites. |

| _gat_UA-28243511-22 | 1 minute | A variation of the _gat cookie set by Google Analytics and Google Tag Manager to allow website owners to track visitor behaviour and measure site performance. The pattern element in the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. |

| AWSALB | 7 days | AWSALB is an application load balancer cookie set by Amazon Web Services to map the session to the target. |

| countryCode | session | This cookie is used for storing country code selected from country selector. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _fbp | 3 months | This cookie is set by Facebook to display advertisements when either on Facebook or on a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising, after visiting the website. |

| fr | 3 months | Facebook sets this cookie to show relevant advertisements to users by tracking user behaviour across the web, on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Google DoubleClick IDE cookies are used to store information about how the user uses the website to present them with relevant ads and according to the user profile. |

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| personalization_id | 2 years | Twitter sets this cookie to integrate and share features for social media and also store information about how the user uses the website, for tracking and targeting. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| vglnk.Agent.p | 1 year | VigLink sets this cookie to track the user behaviour and also limit the ads displayed, in order to ensure relevant advertising. |

| vglnk.PartnerRfsh.p | 1 year | VigLink sets this cookie to show users relevant advertisements and also limit the number of adverts that are shown to them. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _dc_gtm_UA-28243511-20 | 1 minute | No description |

| abtest-identifier | 1 year | No description |

| AnalyticsSyncHistory | 1 month | No description |

| ARRAffinityCU | session | No description available. |

| ccc | 1 month | No description |

| COMPASS | 1 hour | No description |

| cookies.js_dtest | session | No description |

| debug | never | No description available. |

| donation-identifier | 1 year | No description |

| f | never | No description available. |

| GFE_RTT | 5 minutes | No description available. |

| incap_ses_1185_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1185_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1185_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1319_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1319_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1319_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1364_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1364_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1364_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1580_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1580_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_1580_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_198_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_198_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_198_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_340_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_340_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_340_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_374_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_374_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_374_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_375_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_375_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_375_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_455_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_455_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_455_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_8076_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_8076_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_8076_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_867_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_867_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_867_972453 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_9117_2233503 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_9117_823975 | session | No description |

| incap_ses_9117_972453 | session | No description |

| li_gc | 2 years | No description |

| loglevel | never | No description available. |

| msToken | 10 days | No description |