China’s Chang’e-5 Lander Touches Down On The Moon

11:42 minutes

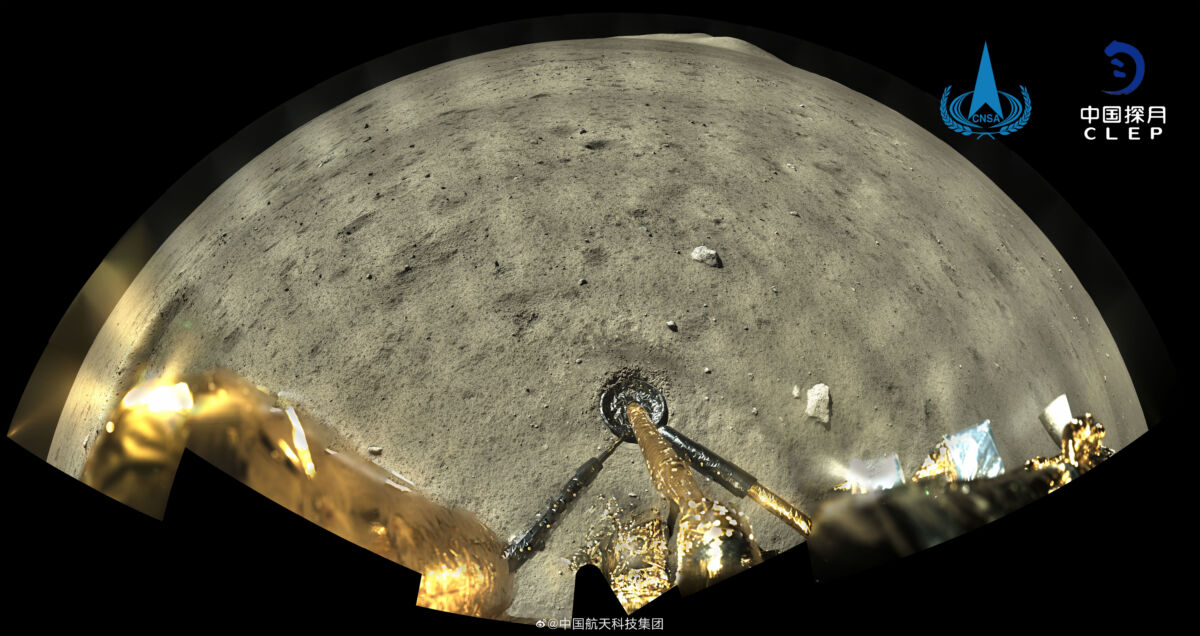

It was an historic week for space news. On Tuesday, China’s Chang’e-5 lander touched down on the moon’s near-side, near Mons Rumker, a mountain in the “Ocean of Storms” region. Over the course of two days, the lander collected several kilograms of lunar soil—the first samples collected in over 40 years. If all goes well, the Chang’e-5 ascension module and its cargo will reunite with the orbiter on December 6th.

The landing of Chang’e 5’s descender and ascender unit.

📹:CNSA/CLEP

ℹ:https://t.co/uAjm4tGl7i pic.twitter.com/P7zK9asBuq— LaunchStuff (@LaunchStuff) December 2, 2020

Also this week, a video from the control tower of the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico captured the moment its final cable snapped. The platform came crashing down on the dish, effectively ending the future—but not the legacy—of this iconic observatory. Ira and Loren Grush, senior science reporter for The Verge, pay tribute, and discuss the historic space news of the week.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Loren Grush is a space reporter at Bloomberg News. She’s based in Austin, Texas.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. This week perhaps the final chapter in the saga of the Arecibo observatory in Puerto Rico was written. The NSF, which owns the radio telescope, had plans to decommission it after two support cables snapped in recent weeks causing irrevocable damage to its dish. Tuesday came the awful sound astronomers had feared. A video from Arecibo’s control tower captured the moment the final cables snapped and the platform came crashing down on the dish—

[LOUD CRASHING]

—effectively ending the mission but not the legacy of this iconic observatory. This hour we’ll search for answers about why this had to happen. But first, we’ll discuss a more positive entry into the space history books. On Tuesday, China’s Chang’e-5 spacecraft landed on the surface of the moon. Its mission? To collect the first samples off the lunar surface in over 40 years.

The lander touched down near a mountain in the Ocean of Storms region of the moon’s near side. Over the course of two days the lander collected two kilograms of lunar soil and if all goes well, will reunite with its return right to Earth this weekend. Loren Grush, senior science reporter for The Verge, is here with the historic details. Welcome back to Science Friday.

LOREN GRUSH: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Now, the Chinese have landed on the moon before but never to pick up the dirt and bring it home.

LOREN GRUSH: Right. This is their third time landing on the moon. The last time they landed on the moon was back in 2019 when they actually were the first to put a robot on the far side of the moon. But this time, yes, they’re actually going to bring back a sample of material so that we can study it here on Earth.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s got a scoop or what? How does it do that?

LOREN GRUSH: So the Chang’e-5 spacecraft is actually four spacecraft in one. When they launched, they all journeyed to the moon together to insert themselves into lunar orbit. And then two spacecraft broke away, a lander and an ascent module, while the service module stayed in orbit. That basically has the propulsion and the solar panels on it.

The lander and the ascent module went down to the surface together, with the ascent module kind of perched on the lander’s head, if you will. And the lander is the one equipped with the tools to actually get the sample. The lander that they just landed on the moon has a robotic arm, and on it it has mechanisms to dig and to scoop up material.

And then when the sample was retrieved, it transferred into the ascent module, which then acted like a mini rocket that took off from the lander and then met up with the service module that was still in orbit around the moon. And then together they’ll travel to Earth. And eventually the fourth spacecraft, a reentry capsule, will take the sample and return that to Earth. And its plan is to land somewhere in inner Mongolia when it comes back down.

IRA FLATOW: Pretty cool. What is this schedule for this? When can we expect the sample to come back to Earth?

LOREN GRUSH: So it’s all happening very quickly. Chang’e-5 launched at the end of November. And it’s going to happen in less than a month because the mission is not designed to last very long on the lunar surface.

They do not intend to last throughout the lunar night, which is a two week period when the moon is plunged into darkness and temperatures reach below minus 200 degrees Fahrenheit. So they’re trying to get this all happening very quickly. And I believe we should have these samples, if all goes well, back on Earth in mid-December.

IRA FLATOW: What is different about these samples from those the astronauts collected back in the 70s?

LOREN GRUSH: So everyone’s really excited about where China has landed for this mission. This part of the moon they believe is actually a lot younger because it’s smoother, so they believe that there’s been some late-stage volcanic activity on this portion of the moon. And so getting samples from this area would go a long way in telling us more about the history of the moon, how it evolved over time, and how our Earth/moon system has evolved in that time frame.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any concern that the Chinese won’t share the data it collected with the global scientific community?

LOREN GRUSH: I think there’s always concern but that hasn’t been the case in the past. We’ve always gotten the data from China’s previous moon missions. They’ve also gotten a little bit more transparent with this mission too.

We actually had a live stream of the launch, they had a live stream of the landing but that cut out just before it occurred. But they’ve been sharing a lot of updates about this mission, so I don’t think anyone should have any fears that what they collect will be guarded or secret. I think there being a lot more open with this mission than in missions of the past.

IRA FLATOW: One of the great mysteries about the moon is how it was formed. We’re really not quite sure of the exact process. Do we think maybe that these samples might help give us some clues to that mystery?

LOREN GRUSH: Yeah, absolutely. Any new sample, any new material that we get from the moon is just another piece of this massive jigsaw puzzle about how the moon formed, how it came to be, and how it looks like the moon that we see in the sky. The moon is a fairly big place, and while we have gotten samples from there, each sample is different. Each part of the moon is different, and so getting samples from an area of the moon that we’ve never been to before is just going to be a fantastic prize for the science community.

IRA FLATOW: You know, I think this news caught a lot of people unawares. Did it come as a bit of a surprise?

LOREN GRUSH: Well, it might have come to a surprise for those who aren’t following the Chinese lunar program. But for those that have been following it, this is not much of a surprise. China has been working towards these lunar missions over time, and they have a very long term plan about how they intend to explore the moon.

And what they’re doing with these missions is just building incrementally upon them. For instance with this particular mission, it’s a very complex mission. They’ve actually sent four spacecraft. And a lot of people are taking note that it has a very similar mission profile to that of the Apollo missions. So there’s speculation of whether or not they’re testing out capabilities that they’ll eventually need when they put astronauts on the lunar surface.

IRA FLATOW: So that might be the end game here, to put people on the moon. And would it be for political bragging rights like the race with the Soviet Union and the Americans was in the 60s? Or are they thinking of commerce there or setting up a moon base or something like that?

LOREN GRUSH: I think any time we go into space there always is some kind of bragging rights involved. But it’s certainly more, I think, for China just building on their capabilities and pushing their abilities in space further. So I think it’s a mixture of both. But they’re definitely trying to explore and do a lot of important science with these lunar missions. So I think it’s a combination of all the reasons we go into space, politics, science, and just seeing what we’re capable of.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the American Space Program. Are we still prioritizing a lunar mission? NASA announced plans under the Trump administration to put the first woman on the moon by 2024. How is that going?

LOREN GRUSH: So that is still very much a priority for NASA, and I don’t see that not being a priority as we change administrations. But of course, things always can change once we get new presidents in office. But yes, for now NASA is still very much focused on its Artemis program. It’ll just be interesting to see what kind of tweaks might happen once a new administration takes office.

IRA FLATOW: Big tweak might be that Elon Musk and SpaceX beats everybody there.

LOREN GRUSH: That’s always a speculation, but I’ll believe it when I see it.

IRA FLATOW: And there are other countries interested in lunar exploration too. I’m thinking specifically of India, which had a failure recently but is planning a soft landing soon, right?

LOREN GRUSH: Yeah. I think the moon is a very enticing exploration goal just because it’s close but it’s not that close so it is very challenging to get to. But a lot of the countries around the world are at the capability where they are able to reach the moon these days. And so that makes it a very great goal to reach.

And like I said earlier, there’s still so much to learn from the moon. So going there does have tremendous benefit in terms of proving out spacecraft capability and also getting materials, and learning, and processing data that the science community really wants.

IRA FLATOW: As long as I have you here– and I know you cover space and related space news– there was important space news this week. And I’m talking about the Arecibo observatory collapsing this week after slowly falling apart. Why was it allowed to sort of degrade like this over the years?

LOREN GRUSH: Well, I think it did catch the engineers and the operators of Arecibo by surprise. It all started when a cable broke in August. And that started kind of a chain reaction of events where they noticed that these other cables that were kind of keeping the entire observatory up and stable were actually starting to fray.

And then a second cable snapped in November. And they did a full assessment of the structure and they found that it was actually on the verge of collapse. And so the platform falling on the dish was actually not unexpected. They thought it would happen. It was just a matter of when. And they were hoping to demolish the structure in a safe way before that happened, but unfortunately the collapse came before that could occur.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s my point. Why demolish an iconic telescope? If you had paid more attention to it, you might be able to save it.

LOREN GRUSH: I think there are going to be a lot of questions about that right now. It’s unclear what kind of maintenance was being done. The Arecibo folks say that they were trying to upkeep the facility, but it really just kind of all happened really quickly at the end of this year. So there’s going to be a lot of questions for them, especially as they move forward and try to clean this up. And hopefully we can get to the bottom of it.

IRA FLATOW: I’m hoping some white knight shows up with private or foundation money and saves it and rebuilds it. So that’s my own wish for having been there and walked around the grounds, and seen what a treasure it has been, and the kinds of explorations it has done, and the materials it has brought back. So we’ll see. That’ll be my New Year’s hope. Thank you, Loren.

LOREN GRUSH: Thank you so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Loren Grush, senior science reporter for The Verge, talking about space with us.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.