Making Peace With The End Of Your Species

17:08 minutes

This is a part of our fall Book Club conversation about the short story collection, New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction By Writers of Color, edited by Nisi Shawl. Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or record a voice message as you read on the Science Friday VoxPop app.

This is a part of our fall Book Club conversation about the short story collection, New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction By Writers of Color, edited by Nisi Shawl. Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or record a voice message as you read on the Science Friday VoxPop app.

Welcome to week four of the Science Friday Book Club’s reading of ‘New Suns’! Our last short story assignment is ‘The Shadow We Cast Through Time’ by Indian writer Indrapramit Das. On a far-off planet, a human colony has been cut off from the rest of space: but they’ve also encountered other life, a fungus-like organism that infects and distorts human bodies into horned “demon”-like creatures. And as one human woman, Surya, approaches her death at their hands willingly, she makes a discovery that speaks of a new future for both species.

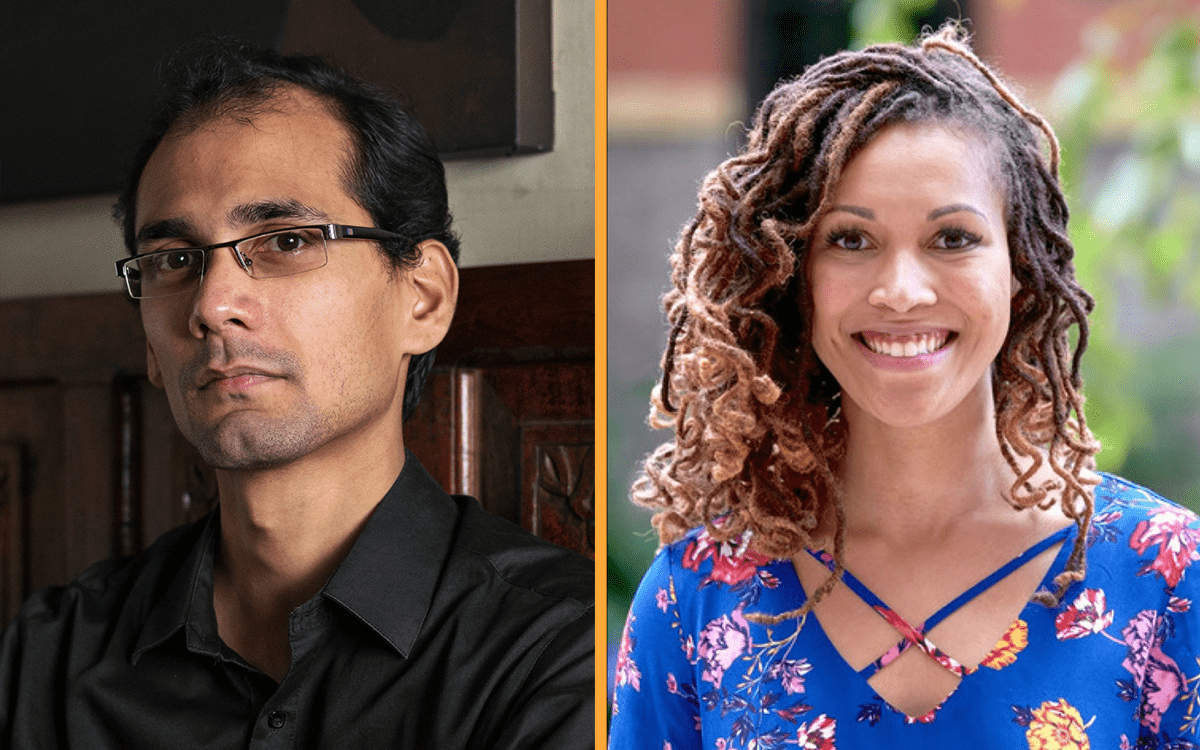

Author Indrapramit Das joins SciFri producer Christie Taylor and Journal of Science Fiction managing editor Aisha Matthews to talk about creating new worlds, and the “modern mythology” of writing science fiction and fantasy.

We’re closing out Fall Book Club with a virtual, call-in celebration! Christie Taylor and co-host Aisha Matthews will chat with speculative fiction author and editor Nisi Shawl, on Monday, October 26. Register now!

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Indra Das is author of The Devourers (book, 2015) and ‘The Shadow We Cast Through Time’ (short story, 2019) and is in Kolkata, India.

Aisha Matthews is managing editor of the Journal of Science Fiction and the director of Literary Programming for the Museum of Science Fiction’s Escape Velocity conference in Washington, D.C..

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The Sci-Fi Book Club has been going places this month. From a world where the dead persist as ghostly shimmers to a future where salesmen aggressively push you to upgrade your home. And as we continue to read the collection, New Suns, Speculative Fiction by People of Color, edited by Nisi Shawl, we continue by asking questions like what makes us human, and how should we treat new life we encounter? Sci-fi producer Christie Taylor has more on this week’s story assignment.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: In the story, “The Shadow We Cast through Time,” Indian writer Indra Das asks us to imagine a human colony on another planet. The wormhole that took them here has collapsed, and so this group of humans is now alone on a new world. But they’re not exactly alone. Another life form is there too, a fungi-like organism that infects other life, including humans, who become these very different looking creatures, that in this story, we call demons.

This story is also a story about accepting death. The main character, Surya, is on her way to the home of these so-called demons to turn herself over to them, as all human elders do when they feel it is their time. But as she does, she learns that the true future of her species may be to combine or hybridize with these demons. Here to talk more about this story with me is Aisha Matthews, managing editor of the Journal of Science Fiction and Director of Literary Programming for the Museum of Science Fiction’s Escape Velocity Conference. Hey, Aisha. It’s been a minute.

AISHA MATTHEWS: Hi, Christie. Good to be back.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So Aisha, we have a story here about encountering aliens, humans establishing outposts in space, and what it means to adapt to loss. What do you make of this story? What did you like?

AISHA MATTHEWS: So as a Butler Scholar, I immediately picked up on the Butlerian influences.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Octavia Butler.

AISHA MATTHEWS: Yes. Particularly reminiscent of the Oankali in her Xenogenesis series. For me, at least personally, I really was interested in the look at symbiosis and hybridity, which I think are some of Octavia Butler’s most interesting and compelling tropes that she introduces in her work.

And I think this story also, in many other ways of interest, kind of aligns with the stories we’ve discussed so far in terms of there’s that element of the ghost story memory of the cultural past and the legacy of the past. And so all of those things, I think, are coalescing for me in this story in a less conventional cultural future, as one that I’m very excited to talk a little further about.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Mhm. Yes. And just going back into how it feels like the other stories, it’s also just kind of creepy. I really love the imagery. It’s very dark. There’s a lot of space and symbolism about outer space and a lot of– we get to these very kind of eldritch fungal structures too, like it’s another story that feels really perfect for Halloween season/spooky season.

AISHA MATTHEWS: Definitely.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So I wanted to bring in author Indra Das, who is the author of this story. He is the author many short stories, as well as the book, The Devourers, which is about werewolves in India. And he joins us from Calcutta. Welcome, Indra.

INDRA DAS: Hi. Thank you for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yes. Thanks for joining us. And Indra, the first question I have for you, just as the author of this story that we’re talking about, is what inspired it? Where did it come from for you?

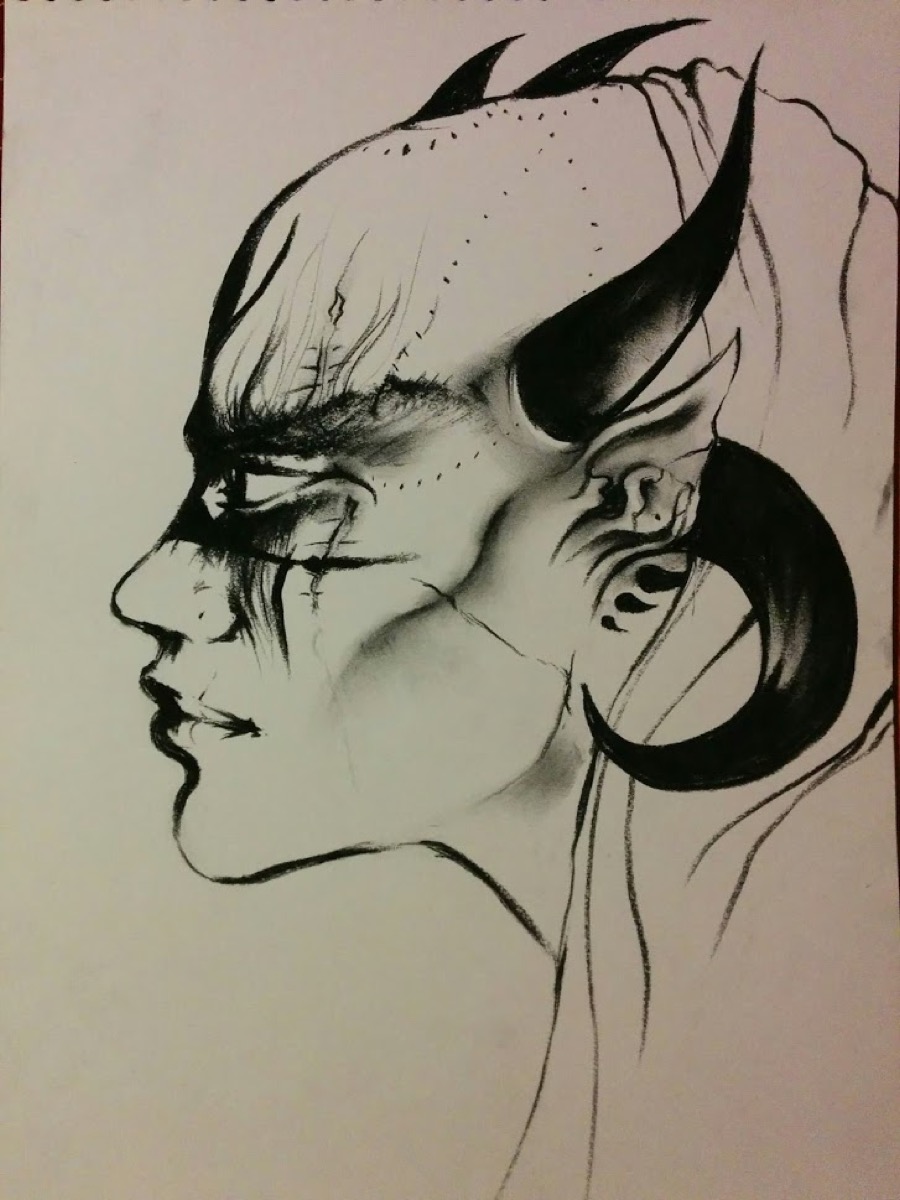

INDRA DAS: There is a very specific place it came from, and that’s a drawing that I did quite a while before I wrote the story. It was just a portrait of an androgynous figure with these dark obsidian horns or antlers growing out of their head. So I just kind of, for whatever reason, I remembered that image that I had drawn, and I started with that.

I usually do that. I don’t plan my stories very much. It usually starts from a particular idea or image, and then I just kind of explore once I can create a scene. So I wrote about an observer watching a figure, like the one that I had drawn. And eventually, it expanded, and I came to discover what this figure was, and the world grew from there.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: And that figure was the demon that we’re trying to picture, that we were supposed to picture when we see this “alien,” quote, unquote.

INDRA DAS: Yes. At first I was thinking of the demon as a specific figure that didn’t come from hybridization, that it was just going to be a humanoid species with horns. And so it might have been a fantasy then, but then I found this more interesting to have them be these revenants, almost.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: One of the things I really love about this story is that we see the colonists, the humans, adapting to the alien, to the other. In some stories we have about humans colonizing other planets, there’s often this point in the story where there’s mass violence or the threat of mass violence, a you versus me situation.

In this one, it’s like the humans encountered this alien species and pretty much immediately said, OK. We’re just going to live with this being part of the planet we’re on. And they’ve incorporated the alien into their culture in a lot of ways, as opposed to trying to impose. Was that a deliberate choice you were making, Indra, in flipping the script again? [LAUGHS]

INDRA DAS: Absolutely, yes. It was definitely a deliberate choice. Because the story is very much a response to the idea of space colonization, which is, of course, inherently weighed down by the real world notion of colonialism, which has done absolutely nothing good for the world.

So a lot of first contact stories are from that viewpoint of trying to– of conflict, of settling somewhere and dominating the land. And I very specifically wanted this story not to be like that, even though the alien life form is dangerous, and it can kill humans. But that’s the same as so many lifeforms on our planet. [LAUGHS]

I mean, so I wanted to explore what it might be like to be a human settlement that isn’t acting in a colonial fashion and is trying to live in similar ways to indigenous tribes. Trying to live with an ecosystem and in balance with it, even though it’s enormously difficult, because they’re outsiders there. They don’t belong in this ecosystem. But because of fantasy and science fiction, we can make them belong in a different way, [LAUGHS] where the ecosystem absorbs them.

AISHA MATTHEWS: One thing I found really interesting in that vein, one of the few directly colonial ideas that I saw, was at the very beginning talking about the history of how the demons came to be. And I think the quote is “this child knew no fear, so they ventured out into this strange city, drunk on freedom, on finding their own world to name and gift with the blessing of human witness.” And so to me, it reminded me of the Christian Genesis story, in many ways, but tied to the later idea that many other planets might consider this place a hellscape because it has these demons.

So it almost seems like the Western hubris of the idea of going out and naming and conquering is what created this demon race or helped them manifest physically in the world anyway. They are portrayed as the foil, as evil. And yet at the same time, these humans are interested in continuing to live with them. So I think that’s an interesting unresolved tension there.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I want to just jump in before you answer that. Because I also really loved that opening story. And there was another line in there that sort of plays to that, which is “you cannot be good in a world that has seen no evil.” And there is this back and forth about morality and what it means to be good and human or deserving of personhood, I guess.

INDRA DAS: Yes. It’s a theme I’m very interested in, how humans formulate morality in relation to their animal existence and the fact that violence is a part of nature. But how human beings create good and evil by doing things that no other animals do and also being aware of what they’re doing in a way that no other animal– as far as we know– is aware of.

And the fact that we’re capable of such atrocity but also so concerned with whether or not we are good, I think that’s one of the essential reasons that we even have storytelling. It’s to constantly try and reckon with what we are and how we differ from other animals. These demons are really representations of that kind of fear of our own violence, of our own mortality. So yes, very, very much a theme that I love exploring.

AISHA MATTHEWS: To your point about the kind of technology and rejecting the more violent means of extracting resources and participating in life kind of brought me back to the techno-spiritualist theme of a lot of these stories in New Suns. And it was interesting to me, clearly these humans used to procreate through gestation pods, through some kind of artificial insemination or artificial ex-viva womb, so to speak. And then they have these machines that can print meat. But then at the same time, the ship is considered their dragon spirit.

So I wondered to what extent the tension between these highly advanced technologies that we obviously don’t have and these human cosmologies of older imaginings of things, like having a clan spirit and things like that. Kind of how that tension is meant to resolve with this environmental concern.

INDRA DAS: Yes. I love folklore and mythology in all its forms. So I love imagining how advanced societies– what their mythology would look like. And particularly in this story, as you mentioned, the folklore hearkens back to something older. And I felt that was appropriate, because this is a small settlement in an incredibly dangerous wilderness.

So it reminded me of exploring the wild when you have nothing, even though they do have very advanced technologies. They’re encroached on all sides by life that they don’t truly understand and that can kill them very easily. So I assume that that would make them revert to this kind of folkloric mythology.

And I think mythology is something we will always be drawn back to when– I mean, we’re at a very kind of strange, advanced but deeply kind of broken stage in human history, where we have a lot of advanced technology, but we simply do not seem to have the means to fix what we’ve done to our planet and to deal with it.

But to come back to mythology, I mean, even– every time, we will always come back to folklore and mythology, even on this kind of hypercapitalized framework of pop culture, of global pop culture, we have superior movies. They’re a modern mythology. We have– you were talking about the dragon spirit. We have people constantly trying to create an analog to that kind of thing, where they will say they have a patronus, or they will use the spirit animal thing. And regardless, the fact is that we are always drawn to mythology, because it is the original fantastical fiction.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Just a reminder that this is Science Friday, and I’m Christie Taylor, talking to author Indra Das, and Journal of Science Fiction Managing Editor, Aisha Mathews, about encountering aliens on another world.

Harking back to how pop culture is modern mythology, which I really love that. I really love that phrasing. If mythology is something that we learn and take lessons from, are there things you hope people especially hearken on to in reading your particular work, Indra.

INDRA DAS: I mean, I wouldn’t want to be too prescriptive when it comes to the way people read my work. I mean, obviously I would hope that they wouldn’t come away with hatred. That’s the main thing, you know. [LAUGHS] That is the essential thing.

I hope people see the stories as a means to think about mortality and the way people relate to each other and the way humanity exists in its own context and the way we should be emphasizing how we can– as you mentioned, Aisha, change is a massive, massive part of all my stories. And I think that is essentially what I want people to come away with, that we have to change. That we absolutely have to break our systems down and rebuild them if we are to get anywhere, if we’re to survive ourselves.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I think I have one last question, which has nothing to do with any of this, but is just the aliens that we’re dealing with here are a colonial life form. They are fungus-like. I personally love fungal lifeforms as a feature of science fiction. What drove you to pick fungus as the kingdom from which this alien life form sprang?

INDRA DAS: I’m not sure when it took that direction. I don’t think it was very conscious. But I have always been aware of the cordyceps fungus, which kind of takes over life forms, and they grow these antlers. So that was definitely an influence in terms of the aesthetics of this life form.

And then the exomycelial filaments and fibers, that was just– it just came to me when I was thinking about these structures, and it felt like a cool way to bring in this hag hair element of this structure that is part of their folklore now. So it was just a cool visual then. And then spores are, of course, very convenient as a science fictional storytelling device, because that way, you can reach across distances and have lifeforms affect other lifeforms.

But yes. Fungi are very cool. And they’re also kind of thematically appropriate to the story, because they thrive on death and decay, and it is a story about death.

AISHA MATTHEWS: One last thing I wanted to say, I feel like I would be remiss not to mention the beauty of your prose. There were so many times where I would think–

INDRA DAS: Thank you. I appreciate that.

AISHA MATTHEWS: I want this embroidered on a throw pillow in my living room, the way you talk about the universe and the darkness of the universe. And it’s seen– there’s a beauty to it that is often, I think, our human fear of death and of the unknown, and the vastness of space is what we’re used to hearing in the language.

So even in the midst of these terrifying things, to hear it described so beautifully and as a clear part of the human continuum puts humanity into a much larger spectrum of existence in a way that I think a lot of science fiction has tried to do, but to varying levels of success. So I really enjoyed this story. [LAUGHS]

INDRA DAS: Thank you.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Seconded.

INDRA DAS: Thanks.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Well, I think on that note, we are out of time. Thank you both. Aisha Matthews is managing editor of the Journal of Science Fiction and Director of Literary Programming for the Museum of Science Fiction’s Escape Velocity Conference. And Indra Das is a speculative fiction author of many short stories and the novel, The Devourers. Thank you.

AISHA MATTHEWS: Thanks, Christie.

INDRA DAS: Thank you again for having me. It was lovely to chat.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: You can go to our website to read an excerpt of “The Shadowy Cast Through Time,” as well as access our online community, weekly discussion questions, and our newsletter. And join us on Monday for a Zoom for a live conversation with New Suns editor, Nisi Shawl. We’re going to talk about what science fiction has to do with now and dig deeper into some of the questions you may have had while reading. All that information is on our website, sciencefriday.com/bookclub. For Science Friday, I’m Christie Taylor.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks, Christie. Oh, and don’t forget that live Zoom taping with New Suns editor, Nisi Shawl. That’s this Monday at 1:00 PM Eastern. Go to our website, sciencefriday.com/bookclub for more information.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.