The Beautiful Spirals Of Sperm Cells On The Move

17:01 minutes

This paper was retracted by Science Advances on May 19, 2021, after readers identified that the described asymmetrical movement of sperm cannot be confirmed using only 3D flagellar waveform data. The five authors of the paper agreed with the decision. To learn more about what happens when scientists make mistakes and how they admit to them, listen to our segment about self-correction in science and the Loss of Confidence project.”

We didn’t always understand the basic science of where babies come from. Theories abounded, but until the 19th century, there was little understanding of how exactly pregnancy occurred, or even how much each parent actually contributed to the reproductive process.

In 1677, a Dutch scientist named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek peered into a microscope and observed, for the first time in recorded history, the side-to-side swimming of tiny sperm cells. He wrote they looked like “an eel swimming in water.” At the time, van Leeuwenhoek thought those cells were tiny worms—maybe even parasites. It took several hundred more years before scientists understood even the crude theory of reproduction as most of us are taught: That a sperm and an egg cell combine inside the fallopian tubes.

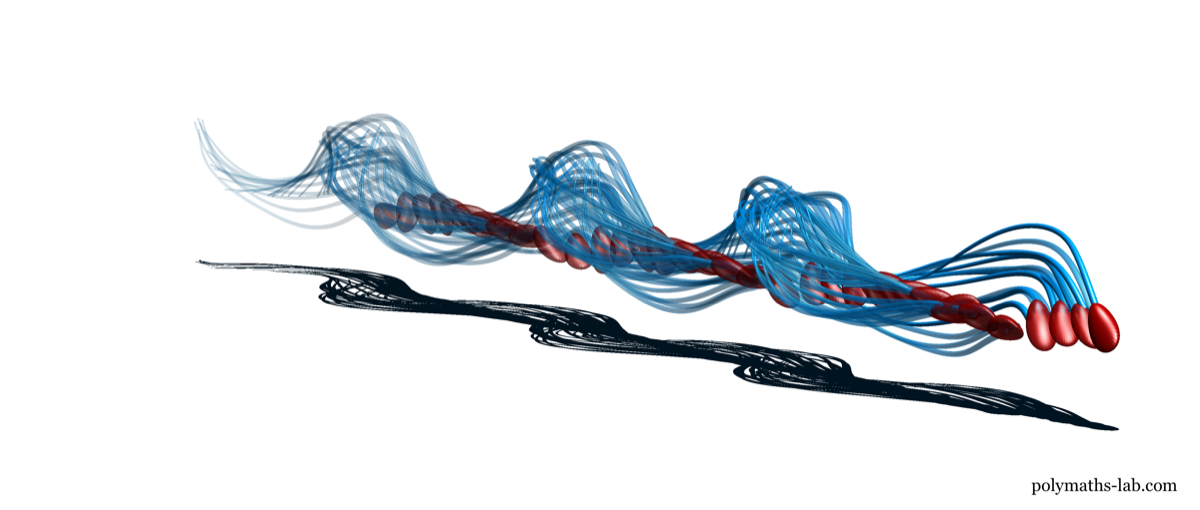

But, as it turns out, even the movement of sperm first described by van Leeuwenhoek—and corroborated ever since in two-dimensional, overhead microscope views—might be wrong. A team of scientists writing in the journal Science Advances this week report finally viewing sperm movement in three dimensions. With the help of 3D microscopy and high-speed photography, they describe a “wonky,” lopsided swimming motion that would keep sperm swimming in circles—if they didn’t also have a corkscrew-like spin that let them move forward “like playful otters.”

Hermes Gadelha, a senior lecturer in mathematical and data modeling at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, talks to John Dankosky about the complexity and beauty of these swimming cells, and why understanding their movement better could lead to breakthroughs in infertility treatment—or even other kinds of medicine.

And, Gadelha’s lab were able to mathematically construct sound based on the frequency of tail strokes in a sperm cell. Take a listen!

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Hermes Gadelha is a senior lecturer in Mathematical and Data Modelling at the University of Bristol in Bristol, United Kingdom.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.