Galileo’s Battle Against Science Denial

16:42 minutes

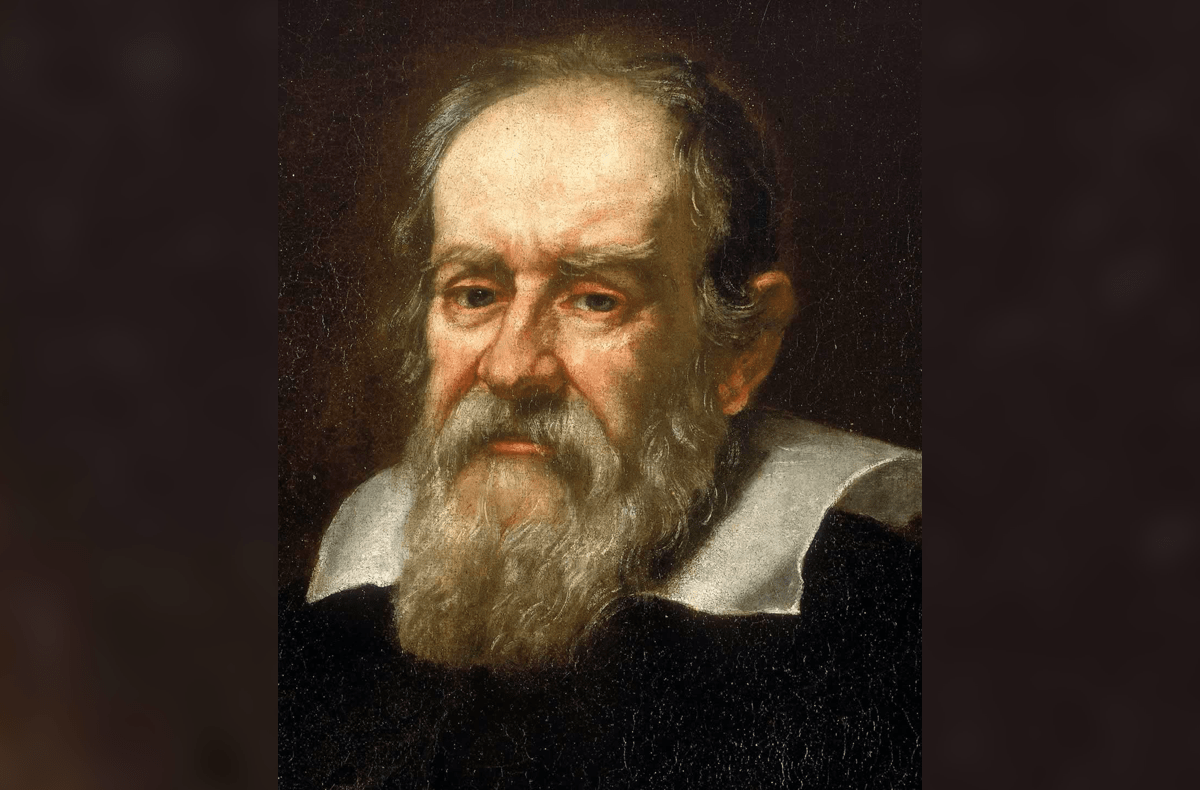

Galileo Galilei is known as the father of observational astronomy. His theories about the movement of the Earth around the sun and his experiments testing principles of physics are the basis of modern astronomy. But he’s just as well known for his battles against science skeptics, having to defend his evidence against the political and religious critics and institutions of his time.

In his new book Galileo and the Science Deniers, astrophysicist Mario Livio talks about the parallels of Galileo’s story to present-day climate change discussions, and other public scientific debates today.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Mario Livio is an astrophysicist, and the author of Is Earth Exceptional? The Quest for Cosmic Life. He’s based in Hoboken, New Jersey.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Galileo Galilei is known as the father of observational astronomy. His theories about the movement of the Earth around the sun and his experiments testing physics principles is the basis of modern astronomy. He’s just as well known for his battles against science skeptics, having to defend his scientific evidence against the political and religious-based critics and institutions of his time.

Sound familiar? My next guest is here to talk about how Galileo’s story is relevant today. Mario Livio is an astrophysicist and author of the new book called Galileo and the Science Deniers. Welcome back, Mario. Always good to have you here.

MARIO LIVIO: Thank you very much for having me here.

IRA FLATOW: Why did you decide to write this book at this time?

MARIO LIVIO: Well, there were several reasons. One is that I’ve always been fascinated by Galileo. I’m an astrophysicist and he founded modern astronomy and astrophysics. Another is that most of the books about Galileo have been written by a science writer, science historians. Not many, if any, have been written by a research astronomer.

So I thought I can bring some, perhaps, fresh perspective to this side of things. And finally, most importantly, Galileo fought against science denial. And unfortunately, we are facing blatant science deniers today.

IRA FLATOW: Is there a real parallel between what he was doing and what is happening in science denial today?

MARIO LIVIO: There are many parallels. I mean, the motivation is not always the same. You see, in his case, it was a clash– not this is often, say, between science and religion. But between science and literal interpretations of scripture. It was the clash. Today, the motivation is somewhat different. For example, let’s say the case of climate change denial. It is usually political conservatism and adherence to certain economical ideas, things like that.

When you talk about the initial reaction to the COVID 19 pandemic, it may have to do with the fact that we are in an election year. So the motivation is completely political. In some cases, religiosity plays a role in the idea to teach creationist idea in science classes in schools.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting to say about the parallels. Because he was at his time, wasn’t he sort of a rock star of science in his time?

MARIO LIVIO: He was. At some point, he became the best known scientist in Europe. But maybe rock stars have lots of followers. I’m not sure how many followers Galileo actually had, but it is true that, for example, his first book about his discoveries with a telescope did sell out very quickly. There were only 550 copies, but still, it was a best seller of the time.

IRA FLATOW: There are many myths about Galileo that you go through in your book, like, well folks, he never dropped those balls off the leaning tower of Pisa.

MARIO LIVIO: No, he did not. He did drop balls though from certain heights, and yeah, measured how they arrived to Earth. But he most probably never did that from the leaning tower of Pisa. Because no documents at the time record that. And Galileo was very, very fierce of people giving him the proper credit.

So he did drop balls and he achieved some important discoveries that way, but not from the leaning tower. There are other things. I mean, I recently wrote an article about whether he ever say, “and yet it moves,” about the Earth. Most probably I conclude he did not. That was identified later a story.

But there is no doubt that he thought that. That was his defiant thing against being convicted by the inquisition. He certainly thought that, in spite of what you think, these are the facts. But he probably never actually uttered those words.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Let’s talk about some of the very clever and imaginative ways he had to test ideas about things. He is credited with modern laws and rules of experimentation, but he doesn’t always get them right.

MARIO LIVIO: Correct. I mean, he started doing experiments. You see, the ancient Greeks, in particular, Aristotle for example, they didn’t do experiments. They thought that the way to understand nature is to sit down and think about it. But Galileo is saying, no, you have to do experiments. You have to do observations. And then, do the reasoning based on what you get from those.

He did fantastic things, do you know. In particular, by wanting to study, for example, freefall. He didn’t have good enough devices to measure short periods of time. So instead, he devised this thing where he used inclined planes and rolled balls down inclined planes. Thereby, slowing down the motion by a lot and enabling him to actually measure these things.

But these theories were not always correct. I mean, for example, he had the theory of tides– ocean tides, which was completely wrong. I mean, he thought that it had to do with the motion of the Earth around the sun, and the motion of the Earth around it– spinning around its axis. And we know that that was not true. It’s actually the influence of the moon. And he didn’t believe it then.

IRA FLATOW: But to his great credit, as you’re right, he created this system of experimentation and re-experimentation and sort of the modern basis of how science is done so that things could be disproven.

MARIO LIVIO: Exactly. He was one of the founders of what today we call the scientific method, which means if you want to explain something, first do experiments and observations. Then, create the model or theory that tries to explain all the observed facts. If the theory doesn’t explain all of the observed facts, it’s not good.

Now, it has to do something more. It has to be able to make some predictions that can be falsified by new experiments or observations. Unless he does that, it’s not really a theory. This is the greatness of science, that it can make predictions that you can then test and see if they are actually correct or not. And Galileo is really the person to do that.

There was one other thing that he did, and that was the mathematization of science. He said that the universe is written in the language of mathematics. This was an incredible statement. Because today, we know that all the laws of nature are written as a mathematical expression. But at this time, this wasn’t the case. And yet, he had this incredibly information that it has to be like that.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk a bit about Galileo becoming embattled with the Catholic church. We touched on it a little bit before when he came out siding with the Copernican ideas about the Earth revolving around the sun and his own theories. What was the main issue that Galileo had with the church?

MARIO LIVIO: So the issue really was it was not against religion. Galileo himself was a religious person. It was against literal interpretations of the texts. He argued, look, the Bible is not a science book. And it was written for the common people to understand. He also had this very strong statement which said that he never believed that God who has given us intelligence and our senses of reasoning, wished us to abandon their use.

So he said, whenever there is a conflict between what observations and experiments tell, in a literal interpretation of what’s in the Bible, you have to change the interpretation. Because you say the Bible doesn’t do errors. It’s just that we interpret it incorrectly. That’s the point.

So as a result, however, he didn’t convince everybody, especially the inquisition, and he was put on trial.

IRA FLATOW: You compare Galileo to Einstein’s views on religion and science. How did they differ?

MARIO LIVIO: They did differ. I mean, they were both great scientists, of course. But their views on religion were rather different, almost orthogonal, in some sense. You see, Galileo thought where he advocated that the Bible is not a science book. It was never written as a science book. So it was written for our salvation.

So the language, in terms of science, was certainly not precise, it’s not mentioned in the Bible, things like that. But he did see it as the guides to moral behavior, ethics, and things like that.

Einstein, on the other hand, when asked whether he believed in God, how religious you was, he answered that he believed in the god of Spinoza, the great philosopher. In the sense that he was in awe in front of the beauty, wonders of the universe, but he did not believe in a personal God. A God that interferes with the actions of humans and punishes or rewards and things like that. That he did not.

IRA FLATOW: And so what happened to his career after that? What did you discover about the rest of his life?

MARIO LIVIO: Well, he was found guilty. Vehemently suspected of heresy. He was condemned to house arrest, which he did for 8 and 1/2 years. For the rest of his life, he was on house arrest. If you think that today, being shut in place for two, three months. He was in his house on house arrest for 8 and 1/2 years.

And all his books were put on the index of prohibited books. And they stayed there until the middle of the 19th century. Even reprints of his books that had already been created were not allowed. This effectively– it didn’t finish his career. Because the house– in his house, he actually wrote his last book, which was this great book on mechanics.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. The idea of truth comes up in conversations that we’re having today, with the idea of fake news. What are your opinions about that?

MARIO LIVIO: Yeah, well you know, that’s where exactly his statement, apocryphal or not, and yet it moves, becomes so important. Because what that statement says is speak of what you may believe, these are the facts. And he established the ways to determine truths. And the only ways, in this particular case about nature, was through experiments, observations, and reasoning based on the data that you get from that.

The data are there, and you cannot deny the data. Today, unfortunately, we live in a situation where there is not just fake news, there are alternative facts. There are all kinds of words like that. It’s almost the death of facts, if you like. It’s a very sad situation. And this sad situation is leading to, unfortunately, very dire consequences.

I mean, if you look at statements such as– that were at the initial stages of this pandemic. Oh, we only have 15 cases, and so we will have not. This is a total dismissal of the actual facts and of the scientific reasoning. We pay a dear price for that.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think it is the duty of scientists to stand up for beliefs that are outside of science in the way that Galileo did?

MARIO LIVIO: I actually do, yes. I honestly think very strongly about that. But intimidation works today as well as it worked in Galileo’s time, OK? Today, people are not burned at the stake and they are not tortured. But careers are affected, lives are affected. But we absolutely have to– especially when you deal with topics that are so important for life on Earth. I mean, to bet against science it is never a good idea.

But to do so when you have a case like climate change, or when you have a case like the pandemic, where literally the future of life is at stake. I mean, it’s really unconscionable.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Do you think that more scientists today should be speaking up? Are there not enough scientists who are voicing their condemnation?

MARIO LIVIO: I believe that most scientists are voicing their condemnation. I think that what is lacking is people who are also non-scientist and are influencers or are in the political system who actually know that these are the facts. And they are not speaking out enough.

And I’m not talking about those who are convinced otherwise. I mean, there are many studies that show that if there are people who are already have strong opinion about something, it’s extremely difficult to change their opinion, even if they are shown facts that are contradictory.

But I am convinced that in our political system there are people who actually know what the facts are, and know what the right path should be, and they still don’t speak up enough.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting because that was the parallel, up to a point, as you say, with Galileo was that he was trying to present the facts. He had the evidence. He had the experimentation. And still could not convince people of the way the world works.

MARIO LIVIO: Well, there were people that were convinced even if it is that. He had some friends, he had some supporters. Yet, other scientists– Johannes Kepler get was a great astronomer. He was completely convinced of Galileo’s findings and all that. So there were people even at this time. Science is not always right. We know that. All scientists know that science is provisional. It always can be improved.

But it corrects itself, sometimes this takes a year, sometimes it can take decades to correct itself. In Galileo’s case, of course, the science corrected itself relatively fast already by Newton. But it took pope John Paul II until 1992 to declare that Galileo was right.

There is always this somewhat of a tension between who do you convince first and who gets convinced first. I think that the main lesson from Galileo is believing science. And this is as true today, and more true even perhaps today in the middle of a pandemic, than it ever was. Because like I say, science isn’t always right, but science understands that it’s not always right. And it always tries to do– to behave according to the facts in the data.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s a good place to end because we have run out of time. A great conversation. Mario, a fantastic look at something– it’s a great history and it’s a great lesson there. And I thank you for writing it and sharing with us today.

MARIO LIVIO: Thank you very much, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Mario Livio is an astrophysicist, and his new book is called Galileo and the Science Deniers. Great reading. Relevant today as well as relevant forever.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.