Erosion Threatens A Unique Ecosystem

4:32 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Rebecca Thiele originally appeared on Side Effects, a health news initiative led by WFYI Public Media in Indianapolis.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Rebecca Thiele originally appeared on Side Effects, a health news initiative led by WFYI Public Media in Indianapolis.

Climate change is increasing erosion on what’s known as the nation’s “third coast”—the Great Lakes shoreline. And that’s threatening beaches, parks and other recreation areas used by people from cities across the region.

Back in the ‘90s, Nancy Schwab’s family vacation home in Beverly Shores, Indiana, wasn’t as close to Lake Michigan as it is today. She says you would burn your feet on the sand getting to the water in the summer.

“We used to have, I would say, another 100 to 150 feet of beach going far out to where the waves are starting—and many memories of being out here with the family,” Schwab says.

In past winters, Schwab says the ice on the lake used to stretch as far as the eye could see—shielding the shoreline from the harsh winter waves. This winter that icy barrier wasn’t there.

“So much as it’s nice to get those 51 degree days. When we have a 51 degree day, my heart stops because I’m like, we’re just not getting that protection anymore,” she says.

Every day the water inches closer to the road and utility lines in front of her home. Any closer and it will have no heat, no water, and her family won’t be able to reach it from the road.

“It’s very sad that it’s taken this beach that everybody enjoys,” Schwab says.

Erosion isn’t just affecting homeowners—it could also drive tourists away. Millions visit Indiana’s lakeshore every year. In Porter County alone, they contribute more than $350 million to the local economy annually, helping to fund everything from schools to fire departments.

The restaurant Wagner’s Ribs sits about 10 miles from Schwab’s home. Owner Dave Wagner says about a third of its revenue comes from tourists, which is common for small businesses in the area.

If tourists don’t come, Wagner might not need to hire an extra dozen summer workers. He may even have to lay off some full-time employees.

“Everyone who works here supports themselves off the money they make in this building—the servers, the cooks, all of them,” he says. “Most of them, this is their main source of income and if we don’t get that summertime push, it will be—people will lose their jobs.”

Tourism here is closely tied to one of the most unique and sensitive ecosystems in the country. Indiana Dunes became one of the newest national parks last year.

Lorelei Weimer is the executive director of Indiana Dunes Tourism. She says the national park is what puts the region on the map—so if it gets hurt, nearby towns feel the impact. Weimer says its one of the most biodiverse parks in the country.

“Because of these four climates that have come together,” she says. “So it’s a very sensitive area—and so it’s one that’s definitely worth fighting for and one worth protecting.”

The park’s chief of resource management, Dan Plath, says overall Indiana Dunes has been luckier than its neighbors. The park has only had to restrict access to two of its nine beaches due to the erosion.

But if the lake comes up, say, another five feet, he says that’s going to have a much bigger impact.

“We actually have endangered Pitcher’s thistle what lives up in the dunes and if it keeps going, we’re probably going to start getting into an area where we have an endangered species,” Plath says.

Other damage is more visible. Erosion collapsed most of the hundred-foot walkway built so people with disabilities can enjoy the lakeside view.

Officials are trying to restore the park’s beaches, possibly by dumping sand on the beach or scaling back breakwaters so sand can naturally float to shore. Park Superintendent Paul Labovitz says they might even move buildings back from the lake.

“And we haven’t decided that yet, but we’re thinking that way,” he says. “We have to get away from Lake Michigan, building things close to the lake is not a good idea.”

The question is, will the Great Lakes shoreline get a chance to heal? With climate change, it’s hard to say.

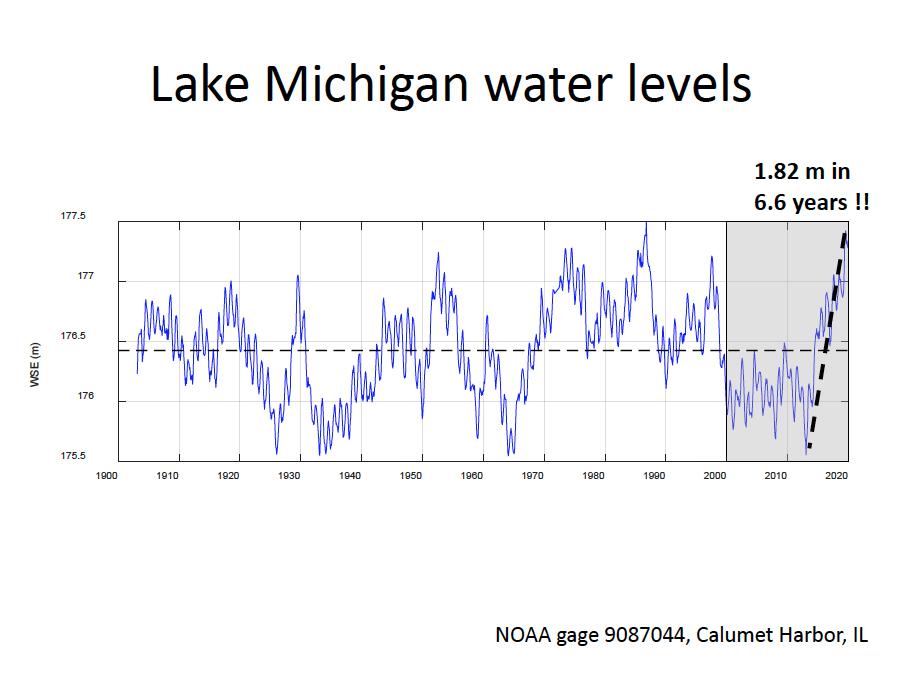

Cary Troy of Purdue University researches coastal engineering along Lake Michigan. He says climate change is creating extremes—very high lake levels in some years and very low levels in others.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the lakes are also expected to get more intense, frequent storms. Both trends are likely to make erosion worse.

“We know that rainfall is increasing over the Great Lakes. So that piece of the lake level budget is definitely increasing,” he says. “But as temperatures warm, there may be also a tendency for evaporation to increase—and that makes it very difficult to predict which effect is going to outweigh the other.”

So while we have high lake levels now, Troy says those levels could go down.

“But I will say that even though the water level can recover fairly quickly, the coastline cannot. The coastline will take a long time to kind of rebuild,” he says.

No less than five Indiana communities have made emergency declarations because of erosion.

One is Beverly Shores, where Schwab’s home is. The town has spent more than $300,000 to fix erosion damage. Town Council President Geof Benson says there’s no money left.

“We started a fundraiser to raise some funds and we’re looking at the possibility of going deeper in debt and refinancing and bonding some more money—because we’ve reached out to the county and they aren’t willing to give us any,” he says.

Schwab always planned to retire in the house and someday pass it on to her grandchildren.

“I’m not going to even think about this house falling into the lake—can’t go there. So we’ll hope for the best,” she says.

In January, two state legislators from the area urged Indiana’s governor to declare a statewide emergency. That would allow lakeshore communities to get federal funding to combat erosion.

Sen. Karen Tallian (D-Ogden Dunes) describes the letter she got in response:

“Which basically said, ‘Sorry, we can’t help you. There hasn’t been any destruction of infrastructure that would get us to an emergency declaration.’ And I called about it because I said,’ Hey, look, we’re trying to prevent destruction.’”

In February, Gov. Eric Holcomb issued an executive order to help gather information so that Indiana could declare an emergency if needed. But the state has yet to follow through with that declaration.

Vivek Rao of Indiana University’s Arnolt Center for Investigative Journalism contributed research and graphics.

“From Rust to Resilience: What climate change means for Great Lakes cities” is a collaborative reporting project that includes six members of the Institute for Nonprofit News (Belt Magazine, The Conversation, Ensia, Great Lakes Now at Detroit Public Television, MinnPost and Side Effects Public Media) as well as WUWM Milwaukee, Indiana Public Broadcasting, and The Water Main from American Public Media. This story is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative. For more information, go to pulitzercenter.org/connected-coastlines.

Rebecca Thiele is an energy and environment reporter at Indiana Public Broadcasting in Bloomington, Indiana.

IRA FLATOW: And now, it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA News.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO.

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. Indiana’s Lake Michigan shoreline is a boon for tourism in the Midwestern state. But due to climate change, shoreline erosion is increasing, creating problems for homeowners, beachgoers, and infrastructure. Joining me to talk about this story is Rebecca Thiele, energy and environment reporter for Indiana public broadcasting in Bloomington, Indiana. Welcome to Science Friday.

REBECCA THIELE: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: So tell us what’s going on there. Paint us a picture of how bad this erosion problem has become.

REBECCA THIELE: So you have homes along Lake Michigan that are just feet from the water. Those people who have seawalls, the water is washing over those seawalls and washing out the soil behind the wall.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

REBECCA THIELE: And most importantly, you know, that erosion is getting so close to these homes that it’s threatening water and gas lines. So you know, if these people don’t have water, if they don’t have heat, they’re probably not going to be able to use those homes anymore.

IRA FLATOW: Now tell us for people who don’t live there, why is the water so high? Is this an unusual thing? Is it climate change? What’s going on there?

REBECCA THIELE: So there are a couple of different factors, but one thing that we know is that climate change is having an effect on the Great Lakes. We’re seeing more extreme high lake levels, and just a few years prior, say, about 2011, extreme low levels. So it’s that variability, that fluctuation, and then, also, you couple that with the fact that we don’t really have that ice shelf that we see in the winter. So those really big storms on the lake in the winter, those are just directly hitting those beaches, those dunes, and then those homes.

IRA FLATOW: What have residents said about this issue? What do they have to say?

REBECCA THIELE: I think a lot of the residents have recognized that ice is gone certainly. I think that that’s a big thing for them. I think that really, in terms of what they can do, some are looking into building up their protections, like sea walls. But a lot of them feel pretty trapped and unable to do a lot about this.

IRA FLATOW: And what are the people doing to remedy this issue locally?

REBECCA THIELE: You know, as I said, some people are looking into more protections, like seawalls, like what they call stone toe protection. So those are those stones that you might see along a pier or something like that. Others have looked into what they call beach nourishment, which is where you put sand directly on the beach.

And that’s a little bit of a more “natural way” to try and control erosion. But it’s very expensive. Beverly Shores, for example, the community that I talk about in the story, they tried to do that, and the sand washed away just a few days later. You know, that’s really heartbreaking for those communities.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that’s something I’m familiar with coming from a beach community nearby. That’s what happens. It giveth and taketh away when the water comes with sand.

REBECCA THIELE: Right. I should say also that I did talk with a professor of geosciences, who said that really, the best long term solution is to move away from the lake. But you know, of course, that’s a really hard sell for these communities.

IRA FLATOW: And are they getting any federal help, sort of a disaster relief or something like that?

REBECCA THIELE: Not right now. A lot of these individual towns have declared their own emergencies, but they really want the state to declare an emergency to open them up to that federal funding.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about the Indiana Dunes area. I understand it has a unique ecosystem.

REBECCA THIELE: Yeah, so it’s one of the most biodiverse places in the country. It’s actually really neat. You can see cold weather plants, like the Arctic bearberry plant next to a plant you would find in the desert, like the prickly pear cactus. And according to the National Parks Conservation Association, there are 90 different endangered species of plants. So this is a really special, rare kind of ecosystem, these fresh water dunes along the Great Lakes.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you for taking time to tell us the news about the lakes, Rebecca.

REBECCA THIELE: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Rebecca Thiele is an energy and environment reporter for Indiana Public Broadcasting in Bloomington, Indiana.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.