What You Don’t Know About Well Water Could Hurt You

3:46 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Brian Grimmett originally appeared on KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story by Brian Grimmett originally appeared on KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service.

WICHITA, Kansas — About 150,000 people in Kansas get their drinking water from private wells.

How clean, and safe, is that water? Short answer: It depends.

But new research suggests those wells deliver water tainted with a range of pollutants. Some leaked from dry cleaning operations. Yet far more wells soak up, and deliver to taps, fertilizer that’s been building up in Kansas soil and water over generations of modern farming.

But it’s not up to regulators from Washington or agencies in Topeka to test private well water quality. That falls to individual well owners. With little to no government oversight, some public health officials worry that’s creating a system where far too many people are left vulnerable to potential cancer-causing pollutants and toxins.

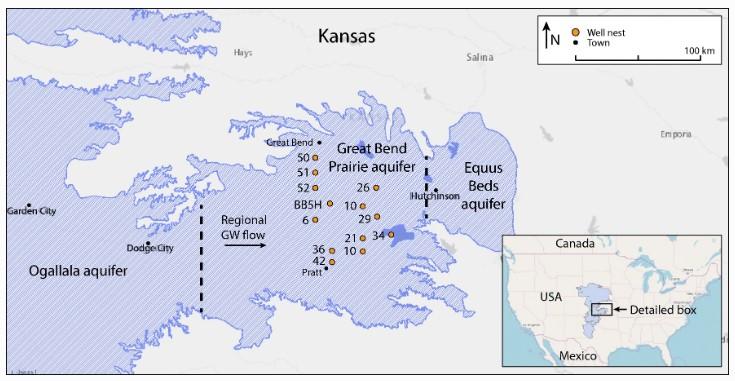

New research from Kansas State University shows that groundwater quality in the Great Bend Prairie aquifer in south-central Kansas rates far worse today than 30 years ago.

The main culprit is a dramatic increase in the amount of nitrate. It’s a byproduct of the Green Revolution of the 1960s that turbo-charged modern farming toward greater yields, especially the use of chemical fertilizers.

Farmers learned that soil laced with extra nitrogen could squeeze more bushels from an acre of land. But not all that nitrogen stays put or gets absorbed in wheat, corn, sorghum and soybeans. Some runs off into streams, or trickles into underground reservoirs.

“The change that we see is comparable to the most extreme change measured by a nationwide study,” Matthew Kirk, associate professor of geology at Kansas State University, said. “So this is a pretty big increase in nitrate.”

High levels of nitrogen in water can lead to shortness of breath. It can even cause death in young children and older adults. The federal Safe Drinking Water Act, which only governs public drinking water, limits nitrate levels to less than 10 milligrams per liter.

When Kirk sampled the water for his research, seven of the 22 wells tested exceeded that limit.

When analyzing the molecules, Kirk said it was clear that the nitrogen was coming from fertilizer leaching into the aquifer from the surface. This particular part of the natural underground reservoir is more vulnerable to land use changes because it’s relatively close to the surface, so the water doesn’t get filtered well. Kirk said it could stand as an early warning for other deeper parts of the broader High Plains aquifer.

Kirk said private well users need to test their water regularly or put the health of their families at risk.

“We do that for municipal water supplies. But for rural well owners, it’s entirely up to them,” he said. “They don’t have to have their water tested unless they want to.”

Because there’s no reporting requirement, there’s also no statewide record of groundwater quality. And even if collecting that kind of data helped officials understand the bigger picture, the movement of water underground is complex. Just because one well is contaminated doesn’t mean the next well over is too.

The National Ground Water Association recommends private well owners do a basic quality test for bacteria and nitrates once a year.

“(But) some people tend to overlook it,” said Brian Snelten, the NGWA president-elect. “It’s one of those things you can forget about. It’s like changing your car oil.”

While a basic test is going to be fine in most cases, there are other chemicals some people need to worry about.

The water in Randi Williams’ house now comes from the city of Wichita. But until a few years ago, she got her water from a private well.

“The lady that sold us the house had us taste the water and hold it up to the light,” Williams said. “And then we had it tested on our own. Since it tested fine, no problems.”

It wasn’t fine.

A toxic plume of dry cleaning chemicals had made its way to their well. It had likely been there for years.

Why didn’t she discover it when she bought the house? Because the toxic chemicals from the dry cleaning plume are odorless and tasteless, and basic tests for bacteria don’t expose it.

She wished she would have been more informed about the potential dangers near her well, such as dry cleaners and underground gas storage tanks.

“Had we known, we probably would have done more testing because, of course, we want to be healthy,” she said.

Databases of some of that information exist, but there’s no system to alert people with water wells nearby. Even if someone did know where to find the information, the average homeowner isn’t likely to understand what they’re looking at.

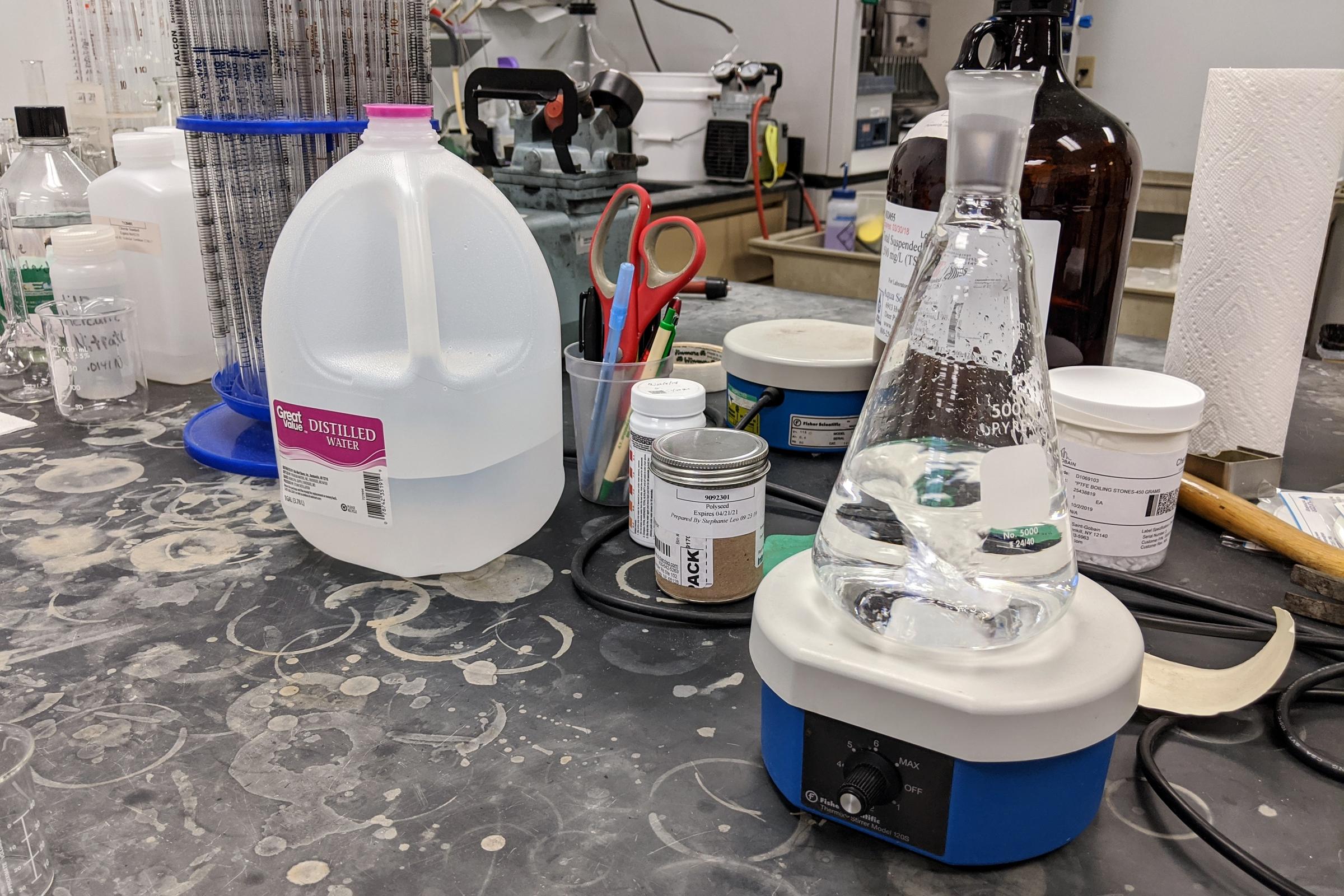

Meridian Labs in Wichita is one of a few places that offers comprehensive residential water testing in Kansas. Their tests range anywhere from $20 for a simple bacteria test, to $150 for a more comprehensive report.

“A lot of times, I will take them through their report step-by-step,” Jessica Jensen, the lab’s technical director, said. “Some people just need that peace of mind.”

Even when well owners discover there’s a problem, the cost of solving it can vary wildly. A sophisticated home filtration system could run several thousand dollars. While cleaning up a large plume, which involves the city or state, can cost several hundred thousand, even millions of dollars.

Elizabeth Ablah researches population health at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Wichita. She said that knowledge gap is a big part of the problem. Without some kind of standardized statewide regulations, it’s too much to expect regular people to fully grasp complex water quality issues.

“We need to be starting to address these issues in a more systematic way rather than this piecemeal patchwork sort of intervention that we’ve been doing,” she said.

She and her colleague, Jack Brown, worked with state agencies, local public health officials and engineering and drilling firms to develop 18 recommendations for improving and protecting well water quality.

The recommendations range from changes in code that would standardize the definition of a nonpublic household water well to defining trigger events for when the state would require well testing.

But they were released a year ago, and so far, nothing has changed.

Ablah’s worried that without some kind of change, the Kansans with private water wells will have to continue relying largely on faith that their water is safe to drink.

“Really there’s no entity that is currently focusing on water quality for non-public water well users,” she said. “And that is a problem.”

Brian Grimmett reports on the environment, energy and natural resources for KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter @briangrimmett or email him at grimmett (at) kmuw (dot) org. The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Brian Grimmett reports on the environment and energy for KMUW in Wichita and the Kansas News Service, a collaboration of KMUW, Kansas Public Radio, KCUR and High Plains Public Radio covering health, education and politics.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERN

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO.

SPEAKER 3: Saint Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. In Kansas, major municipalities are provided with public water which is monitored by the state for harmful contaminants. But in more rural areas of Kansas, many people still use private wells to access groundwater and responsibility for testing is left to the well owner. And as many residents are finding out, testing well water for possible contaminants– all kinds of stuff like VOCs, coliform, nitrates, radon– is not required by their localities. Here to tell us more about this story is Brian Grimmett, energy and environment reporter with KMUW, Kansas State News in Wichita. Welcome back, Brian.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Hey, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Where are these people with the private wells getting the water from, and why isn’t it getting tested?

BRIAN GRIMMETT: So it really depends on– and this is one of the complicating factors– it depends on where you are. So they’re getting their water from underground aquifers, and there are a couple of big ones here in this state, and they pump it up in their private well. And I don’t think Kansas is alone in this. There’s just not really regulations requiring that to be tested. It’s just one of those things where it’s left up to the individual owners, and a lot of people like it that way, honestly.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because I know a lot of people with wells, and it’s up to you to test your own water. I mean, is there no way to set standards then for what happens or to help people pay for the testing? Because I know it costs $100 or more to do that.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Yeah. There has been talk in the past about doing that, and some municipalities and counties have provided some of that help in the past. But over time, some of that budget money just went away and it just wasn’t enough of a priority. And so certainly there are mechanisms to do that for public water system. So if you live in a larger city, that gets tested all the time. And so there are federal standards declared out there for what makes safe drinking water.

IRA FLATOW: Because there’s some nasty stuff in well water, couldn’t there be?

BRIAN GRIMMETT: There could be. So one of the big issues in Kansas is nitrates. And that is as a result of some of the fertilizer that gets put out on the agricultural fields, and depending on how high the groundwater is in your area, nitrates can leach pretty easily into the groundwater where you’re pumping your water from.

IRA FLATOW: Are there some researchers that are recommending that the state require testing of private wells?

BRIAN GRIMMETT: So it gets a little complicated when it comes to that. There are some public health researchers who spent a year, they talked to a lot of stakeholders and they came up with these 18 recommendations. They didn’t go as far as saying that it should be required, but they did come up with a bunch of other ideas, including one of the big problems here is letting residents know when their water might be contaminated.

We’ve got a good idea of where some of these hotspots are, or maybe you live close to a underground gas storage tank, but it’s hard to make that connection between we know that there’s an underground gas storage tank there and letting nearby homeowners know, well, maybe you should be checking your well more frequently than you are.

IRA FLATOW: It’s just simple telling people to do this would go a long way.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Yeah, I mean it’s one of those things– the recommendations. And I talk a lot of people. They know that they should test their well on an annual basis, but it’s like changing the oil in your car or getting your air conditioning unit checked out. Just ’cause you know you should do it doesn’t mean you do it.

IRA FLATOW: Been there, done that, Brian. Thank you for taking time to be with us today. Brian Grimmett, energy and environment reporter with the KMUW and Kansas State News in Wichita. Thanks again.

BRIAN GRIMMETT: Thank you.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the host and executive producer of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.