Looking Back At The Pale Blue Dot

45:56 minutes

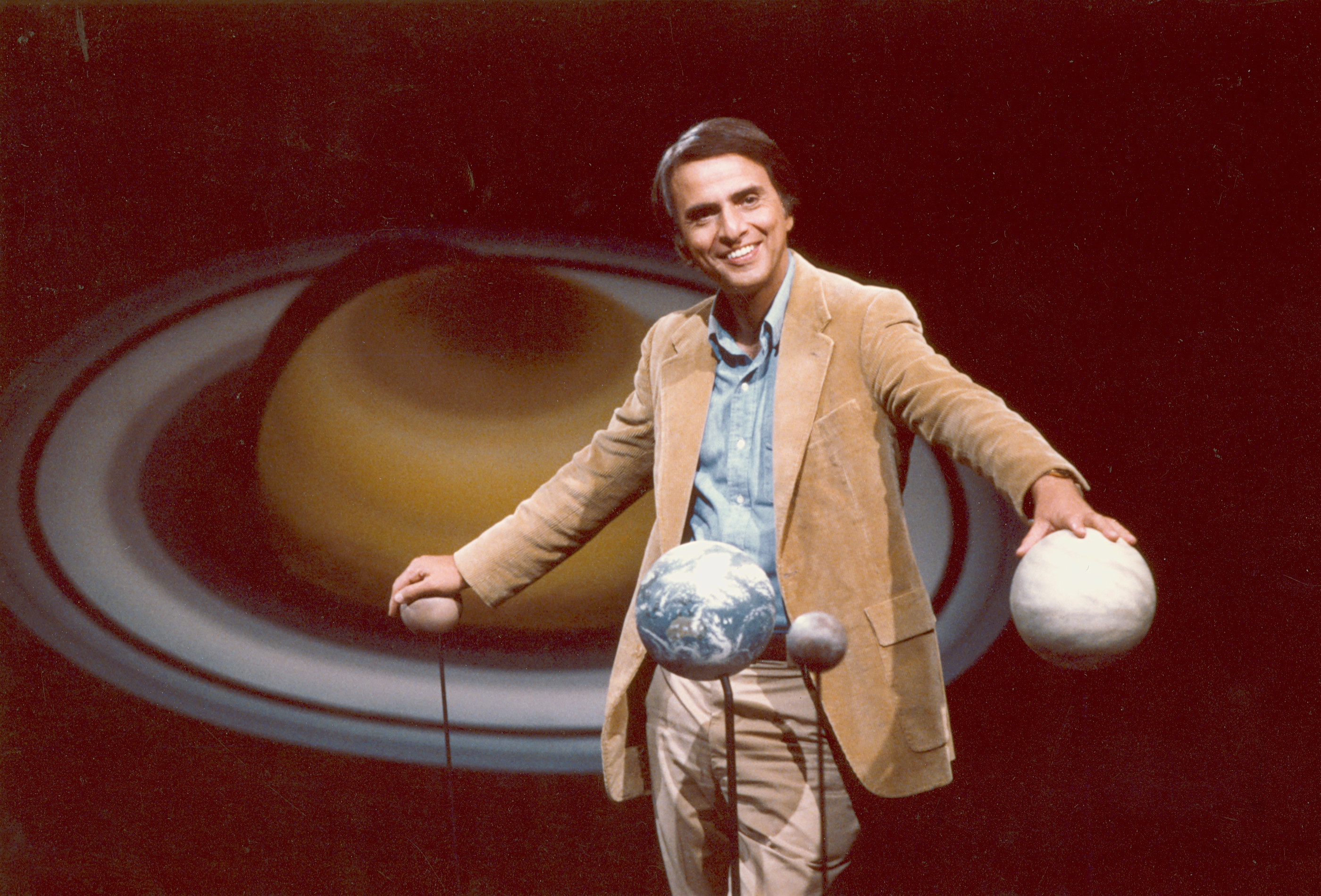

As we make our way towards the end of the year, many people like to step back and take a look at the Big Picture. Few people could put the cosmos in perspective better than astronomer Carl Sagan. And that’s why we’re taking this opportunity to take another listen to this classic conversation with Sagan, recorded December 16, 1994, twenty-five years ago this month.

His book Pale Blue Dot had just been published, and the movie Contact was still in the planning stages. Ira and Sagan talk about U.S. space policy, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, the place of humans in the universe, and humanity’s need to explore.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Carl Sagan authored The Demon-Haunted World (Random House, 1995), among other books, and was the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. As we make our way towards the end of the year, it’s a good time to step back and take a look at the big picture, and I mean really big.

Few people could put the cosmos in perspective better than the late astronomer Carl Sagan. And that’s why we’re taking this opportunity to take another listen to this classic conversation with Sagan, recorded 25 years ago this month. His famous book Pale Blue Dot had just been published. And as you’ll hear, the development of a movie called Contact was still just in the planning stages. We talk about US space policy, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, and the place of humans in the universe. Here’s Carl Sagan on Science Friday recorded December 16, 1994.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We’d all like to think that we’re pretty much the center of attention, the center of the universe. But in the words of Carl Sagan, “We live on a routine planet near a humdrum star, stuck away in an obscure corner of an unexceptional galaxy which is just one of 100 billion galaxies in the universe.”

And if you think that sounds depressing, consider this. There is no guarantee that our boring little rocky planet will be around forever. If we don’t destroy it, maybe a stray asteroid will. And so where does that leave us? Astronomer Carl Sagan might say it brings us back to our roots as explorers and may drive us to become interplanetary, even intergalactic wanderers.

Now, let me welcome my guest. Dr. Carl Sagan is the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Science and the Director of the Laboratory of Planetary Studies at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He is Co-founder and President of the Planetary Society and author of the new book, Pale Blue Dot, published by Random House. And it’s my pleasure to welcome Dr. Sagan. Welcome to the program.

CARL SAGAN: Thanks very much.

IRA FLATOW: Pale Blue Dot. That’s always the first question that every interviewer asks an author. Why the title?

CARL SAGAN: Well, I was an experimenter on the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. And after they swept by the Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune systems, it was possible to do something I had wanted to do from the beginning. And that is to turn the cameras on one of these spacecraft back to photograph the planet from which it had come.

And clearly, there would not be much scientific data from this because we were so far away that the Earth was just a point, a pale blue dot. But when we took the picture, there was something about it that seemed to me so poignant, vulnerable, tiny. And if we had photographed it from a much further distance, it would have been gone, lost against the backdrop of distant stars.

And to me, it– I thought there, that’s us. That’s our world. That’s all of us. Everybody you know, everybody you love, everybody you ever heard of lived out their lives there on a mote of dust in a sunbeam.

And it spoke to me about the need for us to care for one another and also to preserve the pale blue dot, which is the only home we’ve ever known. And it underscored the tininess, the comparative insignificance of our world and ourselves, as you said in your opening remarks.

IRA FLATOW: You know, back when men were walking on the Moon, there was that famous photo of the Earthrise over the Moon, and the, I guess you might call it the bright blue marble compared to your pale blue dot. That sort of led to movements like the environmental movement when people could see us as a united planet without the political boundaries.

CARL SAGAN: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Can we use the pale blue dot as an analogy to that or something that’s even further looking?

CARL SAGAN: That’s it. It’s a set of steps outward. And that Apollo 17 picture, I think, raised many people to an environmental consciousness. And the pale blue dot, at least for me, is– represents the last moment in spacecraft leaving the Earth in which you can see the Earth at all. And the idea that we are at the center of the universe, much less the reason that there is a universe, is strongly, powerfully counterindicated by the smallness of our world.

IRA FLATOW: Why? Whatever happened to the Man In Space program? I don’t have to tell you how popular it was. It was the talk of the ’60s. We all grew up with it.

There was excitement, there was fervor, there was the exploration. Everybody was behind it. A countless amount of money was going into it. Now it just lies fallow and languishing.

CARL SAGAN: You’re absolutely right. I think the first thing to say is that was a historic, a mythic achievement. And 1,000 years from now when nobody will have any idea what GAT is or what the– who the Speaker of the House was in the late ’90s of the 20th century, people will remember Apollo because that was the time that humans first set foot on another world.

But Apollo was not about science. It was not about exploration. Apollo was about the nuclear arms race. It was about intimidating other nations. It was about beat the Russians.

And when we did beat the Russians, then the program was ended. And the clearest indication of that is the fact that the last astronaut to step on the Moon was the first scientist. As soon as the scientists got there, the program was over. People said, why are we wasting our money on science?

Now, lately– I mean in the ’70s, and ’80s, and ’90s– NASA has been very– for the man program, the human program– I hate to use the word “man” because it’s– there are women astronauts. In the human program, we’re shuttle-oriented.

What Shuttle typically does is puts five, or six, or seven people in a tin can 200 miles up in the air. And they launch a communications satellite or something that could just as well have been launched by an unmanned booster. And then the newts are doing fine, or the tomato plants didn’t grow.

Or now, with the next one, they’re going to see how soft drinks taste in low Earth orbit, for heaven’s sake. And then they come back down again. And they say, oh, we’ve had another exploration. That’s not exploration. That’s like driving a bus over the same highway 200 miles.

IRA FLATOW: That’s Cola wars.

CARL SAGAN: The Cola wars. Whereas if NASA had gone on to send humans to near-Earth asteroids or to land on Mars, the enthusiasm would have been maintained at a very high level.

Now, I don’t say that it’s NASA’s fault. NASA cannot make that decision on its own. It has to be made at a much higher level. But that decision was not made. NASA was left to its own devices.

And that’s why we have a falling off of interest in the space program for excellent reasons. People aren’t stupid. They understand we’re not going anywhere.

IRA FLATOW: You make a case for colonizing space different than most people do in this book. Your tack in this book is that you argue, let’s not go out in space for things you could argue for– science, exploration, education. You argue that we have to colonize space because that’s the only way we might survive in the future.

CARL SAGAN: That’s right. I’m a big fan of robotic space exploration. I have been involved with it for 35 years.

If you want to do science, that’s the way to go. It’s cheaper. It doesn’t risk lives. You can go to more dangerous places and so on.

But as for Apollo, as with Apollo, the only justifications that will work in the real world are, one– for human spaceflight– are ones that involve some much broader political or historical agenda. And I believe there are three. One is emotional.

And a lot of people feel it. I know a lot of people don’t. And that is we come from wanderers, from hunter gatherers. 99.9% of our tenure on Earth was in that condition, no fixed abode. It was long before we had villages and cities.

And now the Earth is all explored. We’re in some sedentary hiatus. And I think a lot of people long for some exploration. You don’t have to do it yourself because of virtual reality. A few people exploring can communicate it to many. On the other hand, if your child is hungry, the appeal of this argument is not very high.

IRA FLATOW: Yet when– parenthetically, when Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 smashed into Jupiter, it was front page news.

CARL SAGAN: Yes. And that–

IRA FLATOW: People were transfixed by this.

CARL SAGAN: And that brings me to the– of course, absolutely. And that brings me to the second and third points, which are much more immediate and practical. While I do not for a moment suggest that the Earth is a disposable planet, and I think we have to make the most heroic efforts to preserve the environment, it is a fact that our technology has reached formidable, maybe even awesome proportions. The environment that sustains us is very vulnerable. The thickness of the atmosphere that we breathe is compared to the size of the Earth about the thickness of the coat of shellac on a schoolroom globe.

And that being the case, there is a chance that we will do ourselves in. We’re certainly a danger to ourselves. I would like to see self-sustaining human communities on other worlds in the long run– it’s no big hurry– so that we hedge our bets or diversify our portfolio. Clearly, our chances are much greater if we do that.

And the third point is there is a specific danger that we are now able to identify. And that’s connected with what you just said about Shoemaker-Levy 9 slamming into Jupiter last July. The Earth lives in a bad neighborhood in space. We orbit the sun amid a swarm of an enormous number of asteroids and comets.

And you just take one look at the distribution of these orbits. And it’s clear that the Earth has to run into them or they into us. Most of them are little, burn up in the atmosphere, don’t do much harm. But the longer you wait, the more likely it is that a big one will hit.

The ones that hit Jupiter last July were the biggest ones. They were about a kilometer across. They produced a blotch in the clouds of Jupiter that was about Earth-sized. And a kilometer across object is the size, which would cause enormous environmental damage to the Earth. A 10-kilometer object that hit the Earth 65 million years ago wiped out the dinosaurs and 75% of the species of life on Earth.

Now, to deal with this, first of all, we have to inventory these near-Earth objects. Surely we should be busy finding out if there is any danger from any particular object. We’re not even doing that yet.

And secondly, we ought to develop the technique to deal with an errant asteroid or comet if it’s found to be on Earth impact trajectory. And without going into– we can if you want– the techniques for doing that, there’s no way to do that unless we’re out there. So this is, I claim, a very practical reason why in the long term, humans have to be out in the inner solar system at least.

IRA FLATOW: We need to take a break, but we’ll be right back with more of our December 1994 conversation with astronomer and author Carl Sagan in just a minute. Stay with us.

I’m Ira Flatow. Welcome back. If you’re just joining us, we’re stepping into the Science Friday Wayback Machine and turning the dial back to 1994, 25 years ago, to revisit a conversation with the late astronomer Carl Sagan following the publication of his book Pale Blue Dot.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

You mentioned in your book that as far back, or as close I guess I should say, as July of 1989, President Bush, “on the 20th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing on the Moon, announced a long-term–” I’m reading from the page in your book, “a long-term direction for the U.S. Space program called the Space Exploration Initiative. It proposed a sequence of goals including a space station, a return to human– of humans to the Moon, and the first landing of humans on Mars.” And, “In a later statement, Mr. Bush set 2019 as the target date.”

Do you know anybody who talks about this program anymore? Whatever–

CARL SAGAN: No.

IRA FLATOW: Whatever happened to it?

CARL SAGAN: What happened to it is it died in the process of being born, because the Republican administration was not willing to commit any political capital to get it done. It’s very easy to say, we’ll do something by 2019. That’s whatever it is, 3 and 1/2 presidencies in the future. And who knows who will be president then? You can’t commit your successors.

The thing about President Kennedy’s Apollo program was that he made his historic speech in 1961, which said that we would use rocket boosters not yet conceived, alloys not yet invented, rendezvous and docking techniques not even conceived to go to a moon that no one had ever been to. And we would do this by the end of the decade.

And this was announced at a time when no American had even achieved Earth orbit. But the time scale was politically within reach. And the amazing thing is that we did it.

IRA FLATOW: Scope out for us, what sequence of events would you foresee for us to go out and colonize? And where would we start? Where would be a good spot to look to live?

CARL SAGAN: Well, I think there’s a set of steps, the first of which is better scientific exploration of other worlds, so we know the lay of the land, and the development of the technology for a safe survival of humans in space for long periods of time. That ought to be the principal focus of the International Space Station that the United States– project United States is leading. It’s not quite. I think it will probably be, but it isn’t yet.

And there’s a few connected things with that. You would like to test out our ability to hide from solar flares, energetic events from the sun. You don’t want to fry your astronauts. That happens not all that often.

And then eventually, there’s a set of objects which are accessible near-Earth asteroids, the very culprits we are worried about. Some of them are much easier to get to even than the Moon and much easier to get back from than the Moon. Some of them are really strange-looking, as if it’s two worlds glued together, suggesting that we have here in microcosm part of the process that led to the origin of planets. We might be able to learn about our own origins there. And because of the low gravity, we can do all sorts of engineering work there and so on.

But the real test, the real focus ought to be Mars, the nearest Earth-like planet. It has an atmosphere, polar caps, winds, two moons of its own, enormous volcanoes. But most important, it has clear evidence that 4 billion years ago, it was a warm and wet world unlike today.

Four billion years ago is also the time that life arose on Earth. And is it possible that two very similar nearby worlds, life arises on one and not the other? Or did life arise on Mars 4 billion years ago? Might it be, despite the negative Viking results, hanging on in some refugia, subsurface, some oases.

Or maybe it became extinct. And the fossils, chemical and morphological, are waiting for the explorers from Earth. Mars is a very exciting place. And I would say those are the obvious objectives.

IRA FLATOW: Why don’t we go to the phones to Robert in Virginia Beach? Hi, Robert.

ROBERT: Hey, Dr. Sagan, let me first say it’s an honor to speak with you today.

CARL SAGAN: Thank you.

ROBERT: You’re welcome. I have a question. I guess you’ve answered it in part, but I’ll fire it anyway.

Seems to me that we’re doing a lot of things to the environment that may be not irrevocable, but would have an unsatisfying result for us. They always say that nature gets– changes things and compensates, but we may not like what it does. So I’m wondering, with respect to colonization, where would we go?

Where are the likely places we would go? What’s the timetable to get there? And what are the basic steps for us to take before we can get there?

IRA FLATOW: Let me take it a step further and say, let’s say we were to go to Mars. Let’s say we do the intermediary steps and go to Mars. Do we have to– are we going to, as they show in science fiction movies, try to change the atmosphere of Mars and create giant colonies? Are we going to live in shelters there?

CARL SAGAN: Well, see the timescale I’m talking about is not the next few years. We would start in the next few decades. And we would really get going in the next few centuries. That’s the appropriate timescale for the technology.

So first, there would be the first human landing on Mars, an international crew very likely carrying environments in spacesuits and returning to the spaceship overnight. That would be followed by rudimentary habitats, closed ecological systems in which you could live inside a bubble, maybe something like a Biosphere 2 in Arizona. You would grow into a set of these. You can think of them as villages.

But the long-term, the grand possibility– and we don’t know if it’s possible– is to convert the environment, the surface environment of Mars, into something much more benign, much more Earth-like, something that science fiction writers have called terraforming, transforming into something like the Earth. And while this is extremely difficult to do for, let’s say, Venus, it doesn’t look all that impossible for Mars, at least part of the way.

The key point is that Mars is too cold. And the atmosphere doesn’t have an ozone layer. So deadly ultraviolet light from the Sun is striking the surface. Both of those mean put more atmosphere into Mars. And because it’s cold, there is a lot of gases frozen away in the soil, chemically bound to the soil, or there is permafrost, the polar caps.

And there might very well be ways to release the frozen and chemically bound gases already on the surface of Mars into the atmosphere, warm the place up, and shield the surface from the ultraviolet light. We don’t know that. We obviously have to do some more work there.

By the way, one key thing about going to Mars, which looks as if we can pull it off it’ll be much cheaper than otherwise, is to use Martian resources to generate fuel and oxidizer for the return journey. If you don’t have to take your fuel and oxidizer to get back, if you only have to have enough to get to Mars and then there generate the stuff to get back, your– the weight you have to carry to Mars is much less. And the cost of the mission is much less.

IRA FLATOW: How would you do that? What– take it out of the soil?

CARL SAGAN: One most interesting possibility, due to Robert Zubrin of Martin Marietta in Denver, is you carry compressed methane. You combine it with the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. You generate molecular oxygen and combine it with the methane. You generate the molecular oxygen from the CO2. And now you have your fuel and oxidizer.

And for long-term human stays on Mars, the molecular oxygen is used for breathing, the water is used for drinking and bathing. And as much as you can use the local resources, there’s an enormous multiplier factor in how much you save in getting there. There are a set of clever ideas that have not at all been exploited. And it might turn out to be much less grand in terms of fiscal drain and activity than people have imagined.

Now, on the question that you raised at the very top of the show about isn’t this terribly expensive, and don’t we have other enormously pressing needs, of course we have other pressing needs. And that does take money. But look how the arithmetic works out. If we’re not in a hurry, if we’re talking about a few decades, and if the United States were to join with the other spacefaring nations on the planet, this could readily be done without any increase in the existing budgets. If we focused on the proper objectives, we could do this without breaking any banks at all.

IRA FLATOW: And you point out an interesting point, that most people think that the NASA space budget is as big as our defense budget is, when it’s in fact only 5%.

CARL SAGAN: Yeah, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: And I think that’s true. People think, oh, we’re spending all this money in space. When you look at the budget, we’re really hardly spending anything.

CARL SAGAN: It’s true. Just parenthetically, when we think of all those pressing social, and other, and environmental and other needs, and we wonder where to get the money from, the Department of Defense spending, including hidden costs over $300 billion a year in a Post-Cold War era, is a very good place to take a close and hard look.

IRA FLATOW: Talking this hour about exploring our universe with my guest, Dr. Carl Sagan, author of Cosmos. You all know him by that name. And now a new book called Pale Blue Dot.

Dr. Sagan, any new TV stuff or movie stuff? I understand you’re working on a film. Is that correct?

CARL SAGAN: Yes. I wrote a novel in the middle ’80s called Contact about the first receipt of a radio message from an advanced civilization in the depths of space. And now Warner Brothers is making it into a major feature film, as they say.

My wife, Ann Druyan, and I are co-producing and co-writing. George Miller, the Australian director, is directing. And Jodie Foster will be the lead.

IRA FLATOW: Big name!

CARL SAGAN: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Whoa!

CARL SAGAN: Just delighted. So summer of ’96, if all goes well, it should be released.

IRA FLATOW: Well, since you’re helping and producing the film, I guess it would be true to the text then. A lot of movies do not go along with the book version. Can we expect that to happen here?

CARL SAGAN: I would say it’s a little too early to be sure. For one thing, the movies have a different idiom and requirement than books and especially than novels. I could spend a lot of time in a novel telling what’s inside the head of a character. In the movie, you’ve got to show it.

It’s a very interesting discipline, the difference between writing books and writing movies. And we’ve been greatly helped by Lynda Obst, the executive producer, and George Miller in learning this. But so far at least, it is true to the book, although changes to make it a filmic idiom so that it really works in cinema, of course, are being made.

IRA FLATOW: Whatever happened to the SETI project, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence? Is that moot, dead, defunct? Is it–

CARL SAGAN: Well, it’s very interesting. Let me spend just a couple of minutes on that. There are a number of SETI projects. You use large radio telescopes to see if anyone is sending an intelligible message.

Let me say a few words about one such study called Project META, and then I’ll go on to the NASA one, which I suspect is what you’re talking about. META is a program sponsored by a private membership organization, $5 and $10 contributions of members, non-profit organization called the Planetary Society, which you mentioned at the top of the show that I’m president of. After five years of study and two years of follow up, Paul Horowitz, who’s the project director– he’s a physics professor at Harvard– and I published a paper last year in The Astrophysical Journal.

And what we found is this. To discriminate genuine extraterrestrial intelligence signals from other sources of radio waves in space and from a huge radio frequency interference problem down here on Earth, we used a set of discriminants or filters, narrowband transmission. It has to not rotate with the Earth. It has to be stronger than the occasional statistical noise that all electronic systems have and so on.

After we did that, we found there was a handful of events that passed through all the filters. And the five strongest of them, the five most intense putative signals, all came from the plane of the Milky Way Galaxy. Now, that’s where the stars are. And you would not expect that a glitch in the electronics would only go on when you’re looking at the plane of the Milky Way. And so that’s enough to make the heart start palpitating a little bit and goose bumps break out.

But there’s something extremely odd about it. And other search programs have found the same thing. When you go back and look at these places two minutes later, it’s not there, a day later, a month later, seven years later. And we’ve done all that. We never see it again. And in science, a non-reproducible result is almost worthless. You have to be able to go back and check and have other observers who are skeptical or make different assumptions than you check it out.

So we don’t know what that is. Certainly those places in the sky deserve further examination. And we are moving on to a much bigger project called BETA, Billion-channel Extraterrestrial Assay, which Paul Horowitz has almost ready.

Now, at the same time, a still more sophisticated program was supported by NASA. It went on the air in October 1992, funded by Congress, and was ignominiously turned off by Congress just one year later. The argument presented by Senator Bryan of Nevada was that we didn’t really know that there could be extraterrestrial life out there, and also it was too expensive.

Well, of course we don’t know whether there could be. The whole point is to find out. If we knew beforehand, we wouldn’t have to look. And the consequences of success are enormous. I mean, they’re transforming. It’s hard to think of a more important discovery. And as far as cost goes, the NASA SETI program was costing about one attack helicopter a year.

Now, there’s a very nice coda to this story. And that is that while NASA is not supporting it, a number of captains of the electronics industry have made contributions totaling something around $7 million dollars so that the project is going to go back on the air in Australia sometime early next year. And that’s something really great.

The search program is so important, and the technology is now sufficiently inexpensive, that this can go on even without government support. But it sure would be great if the government would change its mind on this.

IRA FLATOW: We need to take a break, but we’ll be right back with more of our December 1994 conversation with astronomer and author Carl Sagan in just a minute. Stay with us.

I’m Ira Flatow. We’re revisiting an archival interview from 1994 with late astronomer Carl Sagan about humanity’s place in the cosmos. It was recorded 25 years ago after the publication of his famous book, Pale Blue Dot.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

All right. Let’s go to Sean in Kansas City, Mo. Hi, Sean.

SEAN: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Hi.

SEAN: I just had a comment, and I’ll take the comment off the air. What I wanted to ask Dr. Sagan was it seems to me that the way to increase space exploration is to show commercial industry that it would be profitable to do so, because I think as soon as you show business that there’s money to be made in space, you’ll have to fight to keep them on the ground. And I just wanted his comments on that.

IRA FLATOW: OK, thank you.

CARL SAGAN: Thanks. I think you’re absolutely right. If there was money to be made, you’d have to fight to keep them off.

IRA FLATOW: You mentioned some– one of the reasons you might go into space is that there might be diamonds.

CARL SAGAN: Wait. Let me– before we get to that, which is essentially a science fiction theme, why is it that industry is not elbowing each other to get into space? And the reason is that there is no commercially viable project that anyone has come up with, except of course for the aerospace manufacturers who have something to do by building the means to get up there. But no crystals, no pharmaceuticals, no ball bearings, no alloys of admissible metals, nothing like that.

The criterion ought to be this– to make your technology in space is going to cost x dollars. Can you produce a cheaper or better alternative product down on Earth for x dollars? And the answer always seems to be yes. When the answer is no, then we’ll have industrialization. But it’s possible the answer will never be that it’s cheaper to do it up there.

Now, there are some exotic possibilities. And Ira just mentioned one, which is there is a single paper in the Japanese scientific literature suggesting that diamonds might be naturally made on Mars more readily than on Earth. And OK, so maybe.

IRA FLATOW: Now we’ve got your attention.

CARL SAGAN: In that case, we can have General Electric and De Beers finance the space program. But you can’t be sure of that. In any case, we have to go to Mars to find out.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. To come full circle on this, so you’re making the argument that the reason we have to go into space is not for commercial reasons but for solely survival, practical survival reasons, is that the odds are better. And you said it, and I can’t remember where. The odds are better of a asteroid or comet smashing into our planet and destroying us, or dying in such a collision, than they are from dying in an airplane crash.

CARL SAGAN: It’s like this. As far as we can tell from the present statistics of near-Earth asteroids, we can ask what is the chance that the Earth will be hit in the next century by an asteroid or comet that will destroy the global civilization? I mean, that’s the right question. And the present answer is 1 chance in 2,000.

Now, you can decide whether that’s a large number or a small number. But by comparison, the chance of dying in a single randomly selected commercial scheduled airline flight is 1 in 2 million. And now, a lot of people worry, especially these days, about flying in airplanes. And they take out insurance policies. All I’m saying is here, also, with the odds 1,000 times higher, we should take out insurance policies.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s take out a policy. Michael, hi. Age 10. Michael, hi. How are you?

MICHAEL: I’m fine. My question is now, if you could get to the center of the galaxy, the Milky Way, what would it look like? Could you colonize it? And how would you get there, by what type of ship, what type of engine?

CARL SAGAN: Really good questions, Michael. And I’m so glad at age 10, you’re that far along. By age 20, I hope you will be making significant contributions to the subject.

The center of the galaxy is about 25,000 light years away. If we could travel almost at the speed of light– we can’t travel at the speed of light– but if we could travel almost at the speed of light, then on board the ship, it could take us very brief periods of time to get there. But as measured from the Earth, it would be 25,000 years for us to get there. So if you went there and fiddled around a little bit and came back, it would be 50,000 years later, and all your friends would be gone.

So that is a requirement imposed on us by special relativity. It’s a law of nature. And it looks very hard to get around that except for an enormously advanced civilization, much more powers than we have. And I talk about that in that novel, Contact, we were talking about before.

What it would look like. Well, see, it’s really– we live out in the boondocks of the galaxy. And it’s dark because the stars are so far apart. At the center of the galaxy, the stars are much closer together. And it is gorgeous. Multi-colored stars, I wouldn’t say touching but very much closer together than they are here.

The idea of making human communities at the center of the galaxy may be, but that’s a dangerous place, the center of the galaxy. It blows up every now and then, and it looks as if there is a giant black hole at the center of the galaxy. I think we ought to stay for a while out here in our remote spiral arm where things are a lot safer.

IRA FLATOW: OK, Michael?

MICHAEL: OK.

IRA FLATOW: You want to be an astronaut or an astronomer when you grow up?

MICHAEL: Scientific engineer.

IRA FLATOW: Scientific engineer. OK. Good luck to you.

MICHAEL: Bye.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for calling. Bye.

CARL SAGAN: That was great.

IRA FLATOW: We got a lot of young callers on Science Friday.

CARL SAGAN: That’s wonderful.

IRA FLATOW: And we’re very happy to invite them to call. I guess sometimes they’re home early on Friday from school or wherever. I don’t care if they’re playing hooky and listening to our program. That’s just fine.

One of the most interesting parts of the book, and you have it right at the beginning toward the front, is most of us, when we think about where would we like to find the origins of life in our solar system that would be similar to the way it evolved on Earth, we’d say, let’s go to one of the planets. Go to Mars, go to Venus.

But you, because you have studied this for a long time, say let’s go to a moon of Saturn called Titan. That’s where we may find those primordial building blocks of life. Why Titan? What’s going on there?

CARL SAGAN: Yeah, it’s such a great finding. And it’s so unexpected. Who would have figured? Well, just as you say, you would have figured Mars or nearby.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

CARL SAGAN: Titan is the big moon of Saturn. And it’s covered with an orange haze layer and clouds. That’s really weird for a moon to have clouds and an atmosphere.

Not just that. The atmospheric pressure is the closest of any world in the solar system to what it is here. And the atmosphere is made mainly of nitrogen, N2, just as the atmosphere of the Earth is.

Now what is that orange stuff? We know now quite reliably– I think we can really be almost confident about it– that it is complex organic matter, including if you drop it in water the amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, and the nucleotide bases, the building blocks of the nucleic acids, the very stuff of life here on Earth. And it’s dropping from the skies like manna from heaven–

IRA FLATOW: But it’s cold. It’s not like–

CARL SAGAN: –onto the surface.

IRA FLATOW: It’s not like–

CARL SAGAN: Absolutely right. So the sum of the building blocks, key building blocks, are being made and are being preserved, you would think, because of the very low temperatures. So they don’t decay. They’re waiting for us. Let’s go find them.

But it’s even better than that. The Saturn system is, of course, much further from the Sun, 10 times further from the Sun than the Earth is. So it has to be very cold. Its 94 Kelvin or something like that on average at the surface of Titan.

And so you would say, look, this is the place where it misses out being an analogy with the Earth because we have liquid water here that’s central for life. They don’t have it there. But we know that the solid surface of Titan contains ice. And when a comet slams into Titan, it produces a temporary pool and slurry of liquid water.

So now we can ask, over the whole history of Titan, what– and for an average place on the surface, how long did it see liquid water? And the answer seems to be something like 1,000 years, 1,000 years in which the organics that fell from the sky are mixed in with liquid water at reasonable temperatures. Is that enough to make a significant further step towards the origin of life? We don’t know.

But Titan is sitting there waiting for us. And we’re going because in three years, a joint NASA ESA, European Space Agency, mission called Cassini is to be launched to arrive in the Saturn system in the year 2004. And an entry probe capable of examining organic chemistry is going to enter into the atmosphere of Titan, sampling as it descends. And if we’re lucky, it will survive the landing and see what’s down there. It’s a very interesting fact that if you want to understand about the origin of life on Earth–

IRA FLATOW: Amazing.

CARL SAGAN: –the best place to go may be Titan.

IRA FLATOW: Amazing. And, of course, a lot of this came out of the Voyager, mostly all of it. The modern stuff that we know came out of the Voyager missions.

CARL SAGAN: Quite right. And the Titan stuff I’ve just been describing is fundamentally based on Voyager data. You, see there is a spacecraft, two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2.

Product of American industry, run by the government via the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of NASA and Caltech, that came in on time, under budget, and vastly exceeded the expectations of its designers. It is responsible for almost all we know about most of the solar system, the Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune systems. And now those two spacecraft, still working splendidly, are on their way to the stars.

IRA FLATOW: Looking back at that pale blue dot. Let’s go to Jane in Eugene, Oregon. Hi, Jane.

JANE: Hi! Thanks for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

JANE: I’m wondering, Mr. Sagan, if you are assuming that we will not trash any new environment that we may create out in space. And if so, what do you base this assumption on?

CARL SAGAN: This wildly optimistic assumption. Of course we are a lot more slovenly than we ought to be. And we are not doing well with our own planet.

JANE: Right.

CARL SAGAN: And you might very well argue, let’s hold off messing up other worlds until we can demonstrate we know what to do with our own. Let’s make the Earth an Earth-like planet before we talk about making other worlds an Earth-like planet.

I would be very concerned along these lines if there were life on some other planet. Then I would say, that planet belongs, whatever the word belong means, to the beings on that planet. And we have a real responsibility to exercise the most extreme care there. But as far as we know, there is no life in the entire solar system except on the third planet from the Sun, the Earth.

IRA FLATOW: Is our society ready for news about life on another planet? If we were to conclusively say we have discovered life someplace else, can we handle that?

CARL SAGAN: If it’s microbial, I think nobody is going to worry about it at all. But if we get a message from another civilization in the depths of space, that’s very different. And I try to imagine what the various reactions of various human constituencies will be in my novel, Contact. I think many people would look at it with an enormous sense of wonder.

You see, if we got a message it would have to be from somebody much smarter than us because anybody dumber than us is too dumb to send a message. We’ve just invented radio. So really smart guys telling us what they know. That means that every branch of human knowledge is now up for reconsideration.

Some people, of course– and not just human knowledge but things like social organization and religion. Some people, of course, will be defensive about it and worry, what have they assumed that isn’t true? And even in science, did we get something wrong in fundamental astronomy? Did we make a mistake in mathematics somewhere? You can see people being really nervous. But the chance to tap in to such knowledge, it’s like going to school for the first time.

IRA FLATOW: I’m running out of time. I have just two minutes left. But while I have you here, I can’t– I have to ask you a couple of science questions.

CARL SAGAN: Please.

IRA FLATOW: One, what is your take on the problem that we’ve just been listening about, the news that the solar– the universe may be younger than some of the galaxies?

CARL SAGAN: It’s fantastic, isn’t it? It’s like someone telling you that their children are older than they are. You know something is wrong. But we’re just talking about factors of two. Either our method of dating the stars is wrong or our method of dating the universe is wrong. Those are the only two possibilities.

I think the most likely case is that we have the age of the stars right, and we’ll find out that there’s something wrong with our dating of the universe. But tune in. It’s a great question.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And the other great question is, what is all the missing dark matter? And do we have any idea? It gets worse all the time, the more we keep hearing more about it.

CARL SAGAN: Well, yeah, there are plenty of ideas and all mutually exclusive. It’s dark matter is just stuff that we know it’s there from its gravitational influence but we can’t see. Well, you, Ira, and I are sources of matter that don’t radiate much into space. And yet, we have some mass.

It might be snowballs. It might be neutrinos with rest mass. It might be black holes. It might be a kind of elementary particle that no one on Earth has detected yet.

We don’t know. It ranges from the prosaic to the extremely exotic. And there, too, we’re going to find out the answer.

IRA FLATOW: It’s very sobering that we could be sitting in objects that 95% of the universe is made of, and we have no idea what it is. That is really a sobering thought about–

CARL SAGAN: I mean, in that way, it’s depressing. But the other way is, look, we’ve discovered that they’re there. And now let’s find out what it is. And we are on an upward trajectory towards learning. And hats off to science for figuring that out.

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you very much for joining me today.

CARL SAGAN: Pleasure.

IRA FLATOW: It’s been a pleasure having you today. Dr. Carl Sagan is Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York and author of the new book Pale Blue Dot published by Random House. And I highly recommend it. Astronomer Carl Sagan recorded on Science Friday, December 16, 1994.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.