The Best Science Books Of 2019

29:03 minutes

This story is a part of Science Friday’s end of year celebrations. Explore the science news that defined the decade, staff stories of the year, geek out over a roundup of science board games, and join the festivities with us in person in New York City at our special event celebrating science news.

This story is a part of Science Friday’s end of year celebrations. Explore the science news that defined the decade, staff stories of the year, geek out over a roundup of science board games, and join the festivities with us in person in New York City at our special event celebrating science news.

In a year jam-packed with fast-moving science news and groundbreaking research, books can provide a more slower-paced, reflective look at the world around us—and a precious chance to dive deep on big ideas. But how do you decide which scientific page-turner to pick up first? Science Friday staff pawed through the piles all year long. Listen to Ira round up his top picks, along with Valerie Thompson, Science Magazine senior editor and book reviewer, and Deborah Blum, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and director of MIT’s Knight Science Journalism program. See a list of their 2019 science book selections. And we have been asking you for your favorite reads of the year. Find your recommendations below!

Plus, Science Diction correspondent Johanna Mayer reviews a lexicological classic, Isaac Asimov’s Words of Science.

Lisa in Plymouth, MN: “My favorite science book of 2019 was The Bastard Brigade by Sam Kean. I love anything by Sam Kean, his books are great. And this one was especially good and exciting. It mixed together World War II, the race to build the atomic bomb, spies, and baseball. What is not to love? It’s a great read.”

Lonetta in Modesto, CA: “I’ve just finished reading Crisis in the Red Zone by Richard Preston. It is the scariest book that I’ve ever read since his last book about Ebola. It will make you look twice at anybody that you encounter who’s sick.”

I really enjoyed Origins: How the Earth Shaped Human History by Lewis Dartnell. I love the interaction of human history and Earth processes in general, and this was such an overview of so many of these.

— Sadhbh Baxter (@DrSadhbh) December 2, 2019

Invisible Women: by Caroline Criado Perez; Deep Medicine: by Eric Topol; Crystal Mesh: by Alicia Mundy

— christymaginn (@christymaginn) November 26, 2019

American Eden, The Dinosaur Artist, and The Poison Squad. @VSJohnsonNYC @williams_paige @deborahblum

— Jeff Grant (@jeffgrant21) November 27, 2019

We have a few!

Our reporters picked some of their favorite science and health books back in September!

Here’s the full list: https://t.co/GCb560G7Lq

— KQED Science (@KQEDscience) December 2, 2019

Bottle of Lies

Bottle of LiesI’ve long thought of Katherine Eban as one of the best medical investigative journalists working today and this book—a fearless, compelling, horrifying look at corruption in the generic drug industry—shows her at her best. It’s partly a detective story, partly a narrative of some unlikely heroes, and wholly revealing in the ways in which corporate greed and regulatory failure put us all at risk.

Superior: The Return of Race Science

Superior: The Return of Race ScienceA deeply thoughtful look at the ways that a sense of white superiority was woven early into the fabric of biological research—and the ways that it continues today. Saini does a brilliant job of creating a connective historical linkage from the white male, Eurocentric biases of scientists like Darwin and Huxley to modern science. We’ve come far, is the message here, but far from far enough.

Midnight in Chernobyl

Midnight in ChernobylThis book reads like a crime thriller, moving so quickly and terrifyingly forward, that it’s only afterwards when you stop to marvel at the painstakingly detailed reporting that gives it such power. Higginbotham’s story of the 1986 meltdown of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant— and the Soviet response of secrecy—combines politics, science, and humanity with grace, style—and a real sense of warning for today.

Listen to a SciFri interview with Higginbotham and read an excerpt of the book.

The Ice at the End of the World

The Ice at the End of the WorldI can’t imagine a list of notable science books today that doesn’t include at least one referencing climate change. This book shines more as a scientific adventure story fraught with the perils of an ice-bound world and as an insightful look at our hard-won knowledge of climate history. But no one can write about ice without writing about its disappearance in a warming world—the book’s conclusion is both lyrical and alarming.

The Optimist’s Telescope

The Optimist’s TelescopeSo as not to be entirely depressing, I want to give this book a shout out. Venkataraman, who worked as a climate advisor in the Obama White House, would have every reason to be depressed herself. But the book is not a despairing appeal for long term thinking but something more positive: a lively and evidence-based look at the ways we can and do think ahead. And even be smart about it.

Lost Feast: Culinary Extinction and the Future of Food

Lost Feast: Culinary Extinction and the Future of Food For every million species on Earth, approximately one goes extinct each year. The species we eat, however, have an extinction rate roughly five times as high. In Lost Feast, culinary geographer Lenore Newman traces the history of “foods we have loved to death”—from the passenger pigeon to the Ansault pear—and offers possible paths towards a more sustainable global food system.

Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past

Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past The addition of aerial photography and satellite imaging to the archaeologist’s toolbelt has been a game-changer for the field. Thousands of previously unknown settlements, tombs and fortresses have been identified using these transformative techniques. In Archaeology from Space, Sarah Parcak takes readers from newly uncovered Viking settlements in Iceland to ancient amphitheaters in Italy, revealing the role of remote sensing technologies in uncovering important clues about our cultural heritage.

Read the full review on the Science Books blog. Listen to an interview with Sarah Parcak on Science Friday and read an excerpt of the book.

Fables and Futures: Biotechnology, Disability, and the Stories We Tell Ourselves

Fables and Futures: Biotechnology, Disability, and the Stories We Tell Ourselves Contrary to the messaging of many genetic tests marketed directly to pregnant women and their partners, happy families can include individuals with disabilities, argues George Estreich in Fables and Futures. As new prenatal screening tools enter the market and we begin to seriously grapple with the idea of human genome editing, we would do well to think deeply about the consequences of such technologies on the rights and welfare of individuals we consider disabled.

Read the full review on the Science Books blog.

The Women of the Moon: Tales of Science, Love, Sorrow and Courage

The Women of the Moon: Tales of Science, Love, Sorrow and Courage Of the 1586 craters on the Moon named after individuals, only 28 are named after women. The Women of the Moon, by Daniel Altschuler and Fernando Ballesteros offers vivid biographical sketches of these women that collectively highlight the often underappreciated contributions of women to early astronomical research.

Read the full review on the Science Books blog.

Superheavy: Making and Breaking the Periodic Table

Superheavy: Making and Breaking the Periodic Table Frustratingly hard to produce and notoriously unstable the so-called “superheavy” chemical elements—those with atomic numbers greater than 103, offer tantalizing hints about the properties of matter at its most extreme limits. In Superheavy, Kit Chapman weaves together historical hunts for these ephemeral elements with contemporary research.

Read the full review on the Science Books blog.

The End of Forgetting: Growing Up with Social Media

The End of Forgetting: Growing Up with Social MediaOnce a burden borne only by child stars, with the advent of social media, young people today are increasingly growing up in the public eye. In The End of Forgetting, Kate Eichhorn discusses the value of being able to leave childhood behind and the perils faced by those for whom youthful indiscretions and opinions are just a click away.

Listen to an interview with Kate Eichhorn on the Science Books blog.

The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb

The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic BombI have been following bits and pieces of this story for years. But have never been able to unite the pieces, until Sam Kean came along. This is a stranger-than-fiction tale of espionage.

Listen to a SciFri interview with author Sam Kean and read an excerpt of the book.

Volume Control: Hearing in a Deafening World

Volume Control: Hearing in a Deafening WorldAs someone who is hearing challenged, reading Owen’s take on hearing was music to my ears.

Listen to SciFri’s interview with Owen and read an excerpt from the book.

The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan’s Cherry Blossoms

The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan’s Cherry BlossomsA botany lesson as well as the story of one man’s passionate crusade. The book vividly evokes these beautiful trees and teaches a lesson about their biodiversity.

Listen to Naoko Abe on Science Friday and read an excerpt of the book.

We’ve all seen technology changing how we communicate and the words we use. But rather than bemoan, McCulloch investigates and teaches us the fascinating new rules.

Listen to Gretchen McCulloch on Science Friday and read an excerpt from the book.

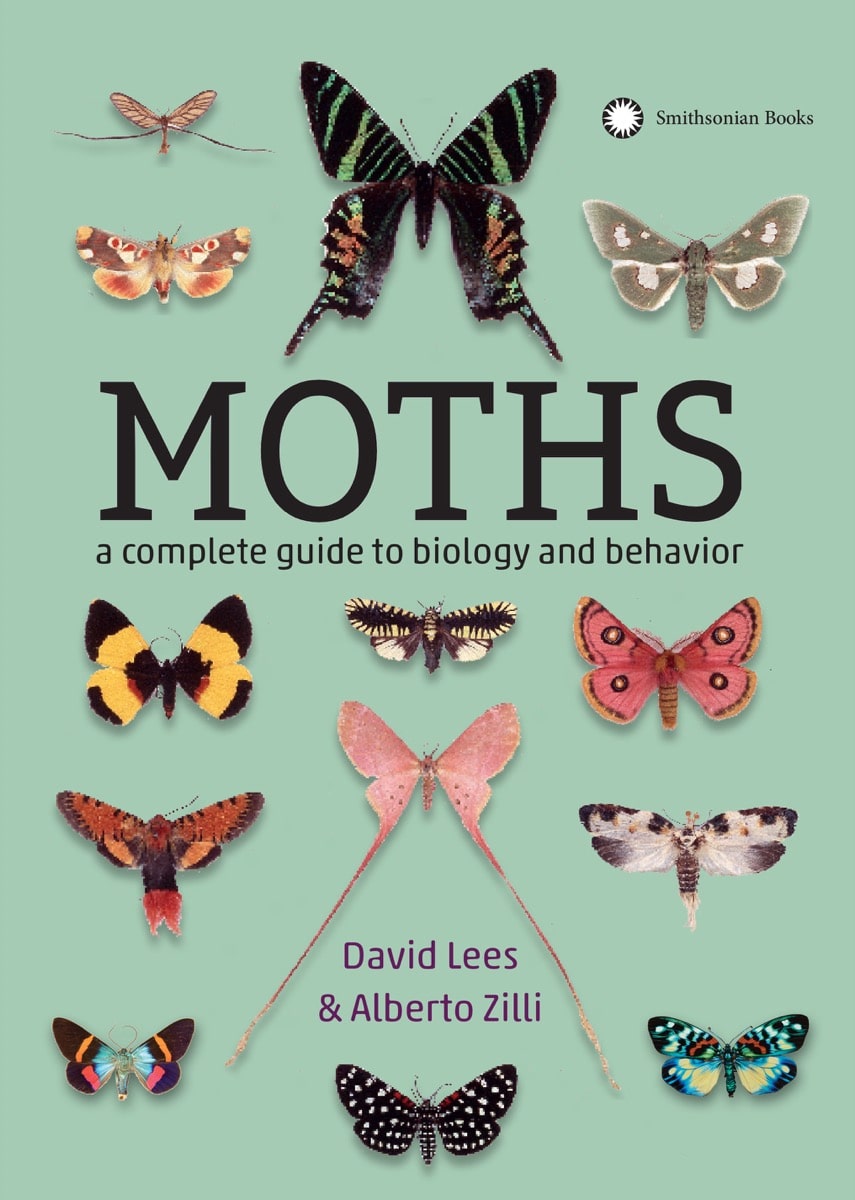

Moths: A Complete Guide to Biology and Behavior

Moths: A Complete Guide to Biology and BehaviorI had no idea how many moths there were or how closely related moths and butterflies were. A beautiful book, to boot.

Learn more about moths in a SciFri interview with one of the authors, Davis Lees and read an excerpt of the book.

Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again

Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human AgainEric Topol is on the cutting edge of medicine and advanced technology. Here he talks about how—counterintuitively—AI can bring doctors and patients closer together.

Listen to Eric Topol on Science Friday and read an excerpt from the book.

Science Friday is an Amazon affiliate; when you buy a book from one of the links above, we get a portion of the proceeds from whatever you buy.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Deborah Blum is a science journalist & author, the publisher of Undark magazine, and the director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Valerie Thompson is a Senior Editor at Science Magazine in Washington, D.C.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. It’s here. Can you feel it? Yeah, the time has come for lists, the lists, the roundups, the best-ofs, the gift guides, the top tens, the 20 must-haves, and beyond. Yes, the year is shutting down. The decade is wrapping up. And everyone is on the prowl for things to carry forward into 2020 whether for themselves or someone else. And here at Science Friday, what we have in abundance is books.

Boy, do we get books. We get, I mean, dozens of– I’d say over 100 books a month. And my producers and I are always thumbing through pages. We’re dog-earing away. So what better way to cap the year than to share with you some recommendations for the best science books of 2019?

And we’ve got some good ones– riveting histories, intrepid investigations, and stories that will give you a new perspective on climate change, modern medicine, and beyond. So grab your library card, put your local bookstore on speed dial, and pull out that pen and pencil. We’ve also been asking you to help us. You’ve come through with some great suggestions, like Leonetta in Modesto, California.

LEONETTA: I’ve just finished reading Crisis in the Red Zone by Richard Preston. It is the scariest book that I’ve ever read since his last book about Ebola. It will make you look twice at anybody that you encounter who’s sick.

IRA FLATOW: Hm, how about Lisa from Plymouth, Minnesota? She had this recommendation.

LISA: My favorite science book of 2019 was The Bastard Brigade by Sam Kean. I love anything by Sam Kean. His books are great. And this one was especially good and exciting. It mixed together World War II, the race to build the atomic bombs, spies, and baseball. What is not to love?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I kind of liked that one also. So we’re going to talk more about all of these books. But we want to know. What was your favorite science book that came out this year? Give us a call, our number, 844-724-8255. You make the call about the book, but only if you make the call– 844-724-8255. Or you can tweet us in this digital age, @SciFri, S-C-I-F-R-I.

Let me introduce my guest, fellow bookworms and readers of note, Deborah Blum, director of MIT’s Knight Science Journalism program, author of many books, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. Always welcome to have you back, Deborah.

DEBORAH BLUM: Thank you. It’s wonderful to be back.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. And Valerie Thompson, book reviewer and senior editor for Science magazine, a neuroscientist by training. And she’s in Washington, DC. Welcome to you too, Valerie.

VALERIE THOMPSON: Thanks so much, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: We had The Bastard Brigade pointed out by one of our listeners. And I thought that was really an incredible book, because I like history of science. I like the history of World War II. I like to learn about all the scientists and the behind-the-scenes stuff of what actually happened in trying to put the Nazi nuclear bomb people out of business.

And it was really, really fun. It was really, really interesting. And I learned a lot from that book. Either of you read that one? It really was a good book.

DEBORAH BLUM: I did. In fact, when I was drawing up my list, I painfully left it off.

[LAUGHTER]

I was like, oh, I’ve got so many good ones this year. I can’t do The Bastard Brigade, although Sam Kean is amazing. So actually, I already felt great when you brought it up.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And you had one of your own to suggest, a historical book, right?

DEBORAH BLUM: I did. And it’s Midnight in Chernobyl by Adam Higginbotham. It’s an amazing book. And I say that as someone who is not like an expert in nuclear power.

But it’s this wonderful story of the Chernobyl nuclear accident in which it’s both history. It’s science history. It’s these amazing descriptions of everything that went wrong and the people involved to the point that you start going, man, he got in there in the most incredibly close ways to some of these issues. And it reads like a thriller, this countdown to disaster and then the countdown to the recovery from disaster. And you’re almost always on the edge of your seat.

And finally, it has the most amazing details. I did not know until I read the book that the Soviet agency responsible for nuclear bombs and nuclear power was called the Department of Medium Machine Building. And I just love that. When reading the book, I’m reading about the Department of Medium Machine Building.

And I think, I must go write a sci-fi dystopian novel about something like that. So the detail of it, it’s a fabulous book. I couldn’t recommend it more.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, we covered that one on Science Friday. Valerie, you had a different kind of nuclear science. It was the 150th anniversary of the periodic table this year, right? And to celebrate, there was a book, of course?

VALERIE THOMPSON: Of course, yes. So I knew I had to choose a chemistry book for this list for that reason. But luckily, I would have recommended Kit Chapman’s Superheavy regardless.

So this book actually gets its name from the so-called superheavy elements. So those are the atomic numbers greater than 103, so dubnium and seaborgium and bohrium. And these are elements that are not found in any appreciable amount of nature, but they can be produced in a lab.

But even so, we can only produce these very tiny quantities. And they last for a few seconds or maybe a couple hours. And they don’t have any known uses. So the question is kind of like, why bother, you know? And so I think it’s a really interesting question because it hints at this larger tension that exists between basic and applied research.

And so advocates for this type of research want to see what happens at these extreme limits of matter. And they expect that these elements are going to exhibit unexpected chemical properties. But then there’s these other people who say, we should really be spending this research money on something more useful.

So the book doesn’t exactly wade into that debate. But his historical reconstructions of the early days of element hunting are just so thrilling. So he tells this example of these two Berkeley scientists who were nearly shot by a security guard because they were driving at breakneck speed across campus at midnight trying to get this sample from the cyclotron to the chemistry lab before it decayed completely. And you’re kind of just like– like I said, it’s so thrilling you’re just kind of left with this feeling that it’s kind of worth doing this work just to see, just because we can.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that’s quite interesting. Let’s go to the phones, because there are lots of people with suggestions. Let’s go to California, to Woodlands. Elizabeth, welcome to Science Friday. Are you there, Elizabeth?

ELIZABETH: Hello, thank you. Can you hear me?

IRA FLATOW: I can.

ELIZABETH: Yes, thank you very much. Love your show.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you.

ELIZABETH: The book that I loved this year– it came out in January– was American Eden about David Hosack, Botany and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic. I had never heard of him before, but he was the doctor to Alexander Hamilton at the duel. He taught at Harvard and Yale.

He collected plants. And he wanted to have a garden with all the plants in the United States in it. He ended up finally corresponding with Thomas Jefferson. He did Linnaeus. And I think the only plates we have from Linnaeus were from his collection.

Anyway, he gathered all these plants, put them in an arboretum. So he had the first arboretum in the US. And it just talks about how we use them for medicine. Some of his medical techniques are still used today.

He was friends with Benjamin Franklin, Jefferson, everyone in the new republic. I mean, it was just amazing how he touched everyone’s lives.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, in fact, the first– he had it right here in New York City. There is a plaque in Rockefeller Center right now.

ELIZABETH: Rockefeller Center, yes, that’s where his garden was. And when that was dismantled, he moved to what is now the Vanderbilt house in upstate New York in the Hudson River area. And the only thing left there are some of the big trees he planted and the roads. All the plants are gone. They even tore his house down to build the Vanderbilt house.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it’s a great book. I agree.

ELIZABETH: But still, he was an American man.

IRA FLATOW: It’s a great book. It’s a great read. And as I say, you can go to Rockefeller Center. And in between all the Christmas decorations now, there’s a little plaque there showing where his arboretum was, the original one. It’s just terrific.

History of science, so it seems that there are a lot of history of science books, Deb and Valerie, that are still yet to be read that a lot of people can read them. Were there any trends in books this year, things people were writing more about than usual, Deb?

DEBORAH BLUM: We’re in the era of accelerating climate change. So you see more and more of books kind of exploring the long-term implications of climate change, where it’s taking us. Is it now?

And the book I picked in that regard is The Ice at the End of the World by Jon Gertner, which is really just focused on Greenland. And I love it in part because it’s not entirely depressing. But so it has a lot of history of science.

And going back to what you said, I love history of science, the way that you can figure out how we got where we are through exploring that. But he looks at how we figured out what Greenland was and all these people who risked their life in insane ways to map it and understand the ice and slide all over this frozen landscape trying to figure out what it meant and figuring out that we have buried atmospheres from eons before in that ice. It’s just an incredible story almost of how hard it is to get these climate change facts. And then, of course, he leads us into the now where Greenland is melting away under everyone’s feet and the way that plays a role in where we’re going with climate change. So it’s a beautifully balanced book.

IRA FLATOW: We had– here are some recommendations coming in on Twitter. We have a book called Radical by Kate Pickert, the history of breast cancer, called excellent. Yeah, Cedric recommends Healing Earth, An Ecologist’s Journey of Innovation and Environmental Stewardship by John Todd. So there you go, another book about climate change. Valerie, do you have a pick that you’d like to throw up before the break here?

VALERIE THOMPSON: Yeah, sure. So I guess kind of on a similar theme, one of my picks this year is Lenore Newman’s Lost Feast. So I think this is something– listeners are probably aware that we’re in the midst of this. They’re calling it this mass extinction, the sixth mass extinction that’s happened on the Earth.

But what I didn’t appreciate before reading this book and what I learned is that the species that we eat historically have had an extinction rate that’s roughly five times as high as the background rate. So in this book, she kind of traces the so-called “foods we’ve loved to death.” And along the way, she critiques our current group global food system.

So for example, she talks about the passenger pigeon, which went from being the most abundant bird in North America to completely extinct within 100 years. And some of that was to be blamed on habitat destruction. But pigeon meat was, in many ways, the first fast food.

It was cheap. It was really easy to produce. And that’s what really did the bird in.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking about the best science books of 2019. And what better way to close out the year than by celebrating one of the most prolific science writers of the century. I’m talking about Isaac Asimov.

He wrote or edited over 500 books. Next month would have been his 100th birthday. And when I was a young reporter, I used to hang out with him at all the science conferences. And he was really an interesting guy to know.

Science Friday word nerd Johanna Mayer is the host of our forthcoming podcast called Science Diction. And she wants to recommend one of Asimov’s lesser-known books from 1959 called Words of Science, and the History Behind Them. It’s an oldie but definitely a goodie. And here is her review.

JOHANNA MAYER: I don’t know about you, but in high school, I remember staring at the vocabulary section of my chemistry textbook with basically full-on dread. Isomerization, hygroscopy, zwitterion, it all just felt so impenetrable. But in his book Words of Science, Isaac Asimov argues that pretty much the exact opposite is true– that those kinds of wonky words and phrases are actually the bridge that brings us into that kind of intimidating world, not the wall that keeps us out, because these words aren’t just conjured up out of thin air.

There’s usually a reason for them or a story behind them. So here’s how the book is set up. There’s a whopping 250 words and phrases starting with absolute zero and ending with zodiac and a pint-sized story or mini history lesson to accompany each of them with just a basic bit of etymology is sprinkled in there too. It’s super digestible. Each word history is just a page long.

Take the word helium. It turns out that the story behind that word stretches back to 1868, a year when there was a total solar eclipse. Scientists were super excited for this because they’d recently developed this new instrument that could observe the sun’s atmosphere. And it worked especially well during eclipses.

So the day of the eclipse finally arrives, and one scientist whips out his instrument. And he notices a super bright yellow line in the spectrum and that he hadn’t seen before. And he concluded that the bright line must be coming from some sort of elusive element that didn’t exist on Earth and was produced only by the sun.

So now, of course, we know that’s not true. But they called that mysterious element helium after the Greek word for sun, Helios. It’s a great story. But I got to be honest. Not every entry in the book lives up to helium.

Angiosperm, for example, did not delight. But when you come across a story like helium, it reminds us that science really is baked into our language. It can just be tough to see that if you don’t speak Latin or Greek or Arabic. The stories get kind of lost, swallowed up in a dusty old word that sounds obscure to our ears. Seems like a bummer.

But in his introduction to the book, Asimov had this really kind of nice thought. There’s a bright side to that. Because now, when we happen upon one of those words and the story just kind of unspools in front of you, it can feel like we’re seeing it for the very first time. You get this sense of wonder and discovery.

Yes, many of the words that we use to talk about science are chock-full of syllables and consonants and can seem maddeningly cryptic and mysterious. But then that’s precisely what makes these words so fun. We get to crack that mystery. Not a bad trade-off, if you ask me.

IRA FLATOW: And that was Johanna Mayer. She is the host of the forthcoming Science Diction podcast, which will dig into all sorts of word stories like the one you just heard about helium. And while we wait for the first episode to come out of the oven, why not sign up for the Science Diction newsletter and stay up to speed with all that wordy nerdy goodness at. sciencefriday.com/sciencediction.

Now, back to the best books of this year with my guest, Deborah Blum, director of the MIT Knight Science Journalism program, author of several books, and Valerie Thompson, book reviewer and senior editor for Science magazine. Our number, 844-724-8255, or you can tweet us @SciFri. Valerie, you had a book you wanted to talk about how we talk about kids with disabilities in the CRISPR age.

VALERIE THOMPSON: Yeah, so we talked a little bit earlier about trends that we’ve seen. And I’ve definitely seen an uptick in books about the intersection of human health and genetic technologies, which is great, because we’re starting to grapple with this idea of human genome editing.

But the book I recommended, George Estreich’s Fables and Futures, stood out to me this year because it does delve into CRISPR and synthetic biology. But it also kind of backs up a little bit and really drills down into this technology that a lot of us don’t even think twice about anymore, which is prenatal screenings. So these screenings are often marketed directly to potential consumers.

And the messaging is kind of upbeat and says, oh, take this test and be reassured that your baby is healthy. But there’s kind of this unspoken part that’s ultimately kind of sinister. And so Estreich kind of delves into that.

And the reference to fables in the title refers to the stories that these types of technologies perpetuate about what’s normal and how we think about the rights and welfare of those who we consider to be disabled. So I think this is really a fundamental question that we really need to grapple with before we move forward. And it’s something that we really need to think about before we start trying to see if we can develop these interventions for genetic disorders.

IRA FLATOW: When you mentioned that, you reminded me of a book I really enjoyed that is also on the cusp of science, technology, and humanity. And that is Eric Topol’s book called Deep Medicine, How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Health Care Human Again. And that really was the surprise of this book. I mean, we’ve been talking to Eric for years. You know of his work.

He’s on the cutting edge of medicine and high technology. And what’s interesting about this book is that, counter-intuitively, he says that high tech can actually bring doctors and patients closer together whereas you might think that high tech is going to take the place of the doctor. And he says, no, the doctor will have more time to talk to you because the AI will do the boring but important stuff.

VALERIE THOMPSON: Yeah, I think that’s kind of the dream. And that’s what people have been talking about for a long time in this area. And I think maybe now with the advances that we’re seeing in AI, maybe that’s more likely to become a reality. So yeah, I think definitely it was a great book.

IRA FLATOW: All right, Deb, hit it.

DEBORAH BLUM: [INAUDIBLE] my life.

IRA FLATOW: Hit it. Hit us up with your next book, Deb.

DEBORAH BLUM: Well, my book is not nearly as positive as to what you’re talking about.

IRA FLATOW: Is it about poison?

DEBORAH BLUM: Poison is always positive, to me, Ira.

[LAUGHTER]

But in a way, so I want to give a shout out to Katherine Eban’s book Bottle of Lies, which is an investigation on corruption and into the corruption of the generic drug industry, and in fact, does deal with the way that some generic drugs– and we saw this year, in fact, with contamination of Zantac– have become poisonous or dangerous. But it’s really an amazing book that focuses on– and it has history, the start of the generic drug industry in India, which was really fostered by Gandhi, which I had not realized till I read the book, who was looking for cheaper medicines for people who couldn’t afford the expensive brand name versions. And he helped and encouraged the setup of an industry where they would reverse engineer the labeled drugs and then make what we now call generic versions.

And then she follows it to the complete corruption– complete is probably a strong word– but massive corruption of that particular industry so that they are not– they can reverse engineer the drug. But they don’t necessarily make that reverse-engineered drug because it’s too expensive. And they slide in different ingredients.

And it’s a narrative story because she’s following this very heroic young Indian whistleblower who’s trying to call this out. And it’s a portrait both of an institution that has become sort of unbalanced by how profitable it is and the failure of the American regulatory industry to the point. There’s a point where she goes– and people who really know this do their best never to get drugs that are made in Southeast Asia.

And I thought, well, that’s not fair. I don’t know where my drugs are made, right? So give me– so we have to hope that this book, which is really a wonderful story if kind of terrifying, will lead us to change. I am a big fan.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and it’s a good time to talk about that too. Let’s go to the phones to San Antonio. Angela, welcome to Science Friday. Go ahead.

ANGELA: Well, I called in for one book and realized that it was from last year. But the one that I appreciated this year was called Dementia Reimagined. And it’s by Tia Powell. And I’ve lost one parent to Lewy body dementia, which is a form of Parkinson’s disease. And then my mother now has Alzheimer’s.

And she chronicles through what’s been happening with Alzheimer’s and dementia as an aging population, what’s happening and what’s going to happen to us, and puts it in into perspective. Which is, there is no treatment. You’re not going to get better. It is terminal. Just like being born, you’re born, and you’re going to die.

But she kind of gives you what to expect. And it almost– in one point, it kind of made me feel like, well, yeah, I did all the right things for my dad. I didn’t put in a feeding tube. I didn’t prolong his life. I made him comfortable and happy.

And then the last chapter is reimagining your own death and basically knowing that if this is in your family what will you do and then preparing for it. And that, to me, was hopeful. Because it was like, you know, this is going to happen. But this is what you can do.

And she was a psychiatrist and became a bioethicist. And I think with this disease, it has to be what’s ethical, because you can do a lot of really stupid things and make that last bit of seeing your parents when they don’t know you very unhappy.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Well, I’m glad it brought you some comfort and gave you some hope for the future. Short time left in our book segment, let me ask both Deb and Valerie. First, Valerie, what do you look for in a book about science? What makes it a good science book? I’ll ask you first.

VALERIE THOMPSON: Well, I think one of the big things I look for, of course, is a good story, like anyone looks for. So there has to be a really good narrative in the book. And then our audience, the readers of Science magazine, are from all fields of science. And so I’m always trying to make sure that we have a good representation from different fields and different types of authors from different types of places.

So it’s really hard to say, to give kind of broad strokes. But it’s kind of one of those things you know when you see it.

IRA FLATOW: Right. And Deb?

DEBORAH BLUM: Yeah, I agree with Valerie that a book that has a compelling narrative that moves sometimes very complicated science forward, like some of the ones we’ve discussed here, is usually a really good book. But I also like books that make me– either surprise me or in some way make me think about science in a different way, add a kind and thoughtful perspective to the way it works. Because– and this I think is true of all really good science books– science is a human enterprise. And we’re looking at something where people are making decisions, sometimes in thoughtful ways, sometimes in ways that are driven by perhaps less noble ideas. And so good science books, to me, at some level, bring the humanity of science to life.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I have a few minutes left. Maybe we can have a lightning round.

[LAUGHTER]

We could go quickly through some of your books, Valerie. I know you have more to recommend. Give me a couple.

VALERIE THOMPSON: OK, sure. The first one I’ll recommend is called Archeology from Space. This is by archaeologist Sarah Parcak. So this is looking at how archaeologists are incorporating remote-sensing technology, so aerial photography and satellite imaging, into their tool kit and how this is kind of helping us uncover thousands of previously unknown settlements and tombs and fortresses.

IRA FLATOW: I think we did that one. Deborah, give me one from you.

DEBORAH BLUM: So I really liked Angela Saini’s book Superior, which is about the history of science, race science, but also the reemergence of it. And I love it partly because its tone is so calm, right? Even when she’s writing about things that you go, oh, that’s so outrageous, she never raises her voice. And she allows everyone throughout this sort of landscape to be heard fairly. It’s a really good book.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. Do you have any? This is an era of the internet and language and also the era of– we covered books on Science Friday of beautiful, how shall I call them, coffee table books. I mean, we always have some wonderful coffee table books. And they’re also very educational. You learn lots of things.

And we had a book about moths that was really, really cool, A Complete Guide to Biology and Behavior by David Lees and Alberto Zilli And I had no idea how closely moths were related to butterflies, this one tiny little difference that they were, and actually, how beautiful the moths were. And this is a great little book. I think it’s a great gift book also. All your books are great gift books, but–

VALERIE THOMPSON: Ira, I was actually looking at this book yesterday. And I was delighted to discover that there’s a subfamily of moths that lives on sloths.

IRA FLATOW: Moths on sloths.

VALERIE THOMPSON: The moths, they help the algae grow on the sloth. And then they lay their eggs in the sloth’s poop or something. But it’s just like moths on a sloth. It’s like the next children’s book. It’s such a great idea. That’s a free idea for anyone listening.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have anything coming up in 2020 we should look forward to?

DEBORAH BLUM: Well, I am excited about Mara Hvistendahl, who was a Pulitzer finalist for her last book, has a book called coming up called The Scientist and the Spy, which is about Chinese espionage of American agricultural products. And I know that sounds really corn. But it is really a fascinating book, at least the early look I had of it.

And Emily Anthes has a book called The Great Indoors. And I’m a big fan of the great indoors, which makes me sound really exciting, I know. [LAUGHS] So I can’t wait to read it.

IRA FLATOW: Valerie, you got any books looking ahead? Are you reading any that you’ll be reviewing?

VALERIE THOMPSON: We’re definitely covering The Scientist and the Spy. But what I was thinking about more for 2020 is that as was mentioned in the segment earlier, it’s the 100 anniversary of the birth of Isaac Asimov this year. It’s also the 100th anniversary of the birth of Ray Bradbury. And these are just these two prolific science fiction authors who have arguably had impacts on the field of science. And so I’m actually– I don’t know of any specific books yet, but I’m really looking forward to seeing what people are going to write about that in 2020.

IRA FLATOW: Start reading The Martian Chronicles and Ray Bradbury stuff too. It’s great stuff.

VALERIE THOMPSON: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you both for taking time to be with us today. And happy reading.

VALERIE THOMPSON: Thanks, Ira.

DEBORAH BLUM: Thanks so much for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: Valerie Thompson, a book reviewer and senior editor for Science magazine, Deborah Blum, director of MIT’s Knight Science Journalism program, author of all kinds of books, especially about poison. [LAUGHS] And you can see all of our book recommendations up on the Sci Fri website. That’s sciencefriday.com/bestbooks.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.