How The Fashion Industry Is Responding To Climate Change

34:06 minutes

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

This story is part of Degrees Of Change, a series that explores the problem of climate change and how we as a planet are adapting to it. Tell us how you or your community are responding to climate change here.

Recently it seems like the whole world’s been talking about climate change.

All week you’ve been hearing from us and our partners in the media report on climate change as part of the journalism initiative Covering Climate Now. And on Friday, students around the world are skipping school to voice their support for taking action against climate change as part of the Global Youth Climate Strike.

It seems like right now, climate change is trending.

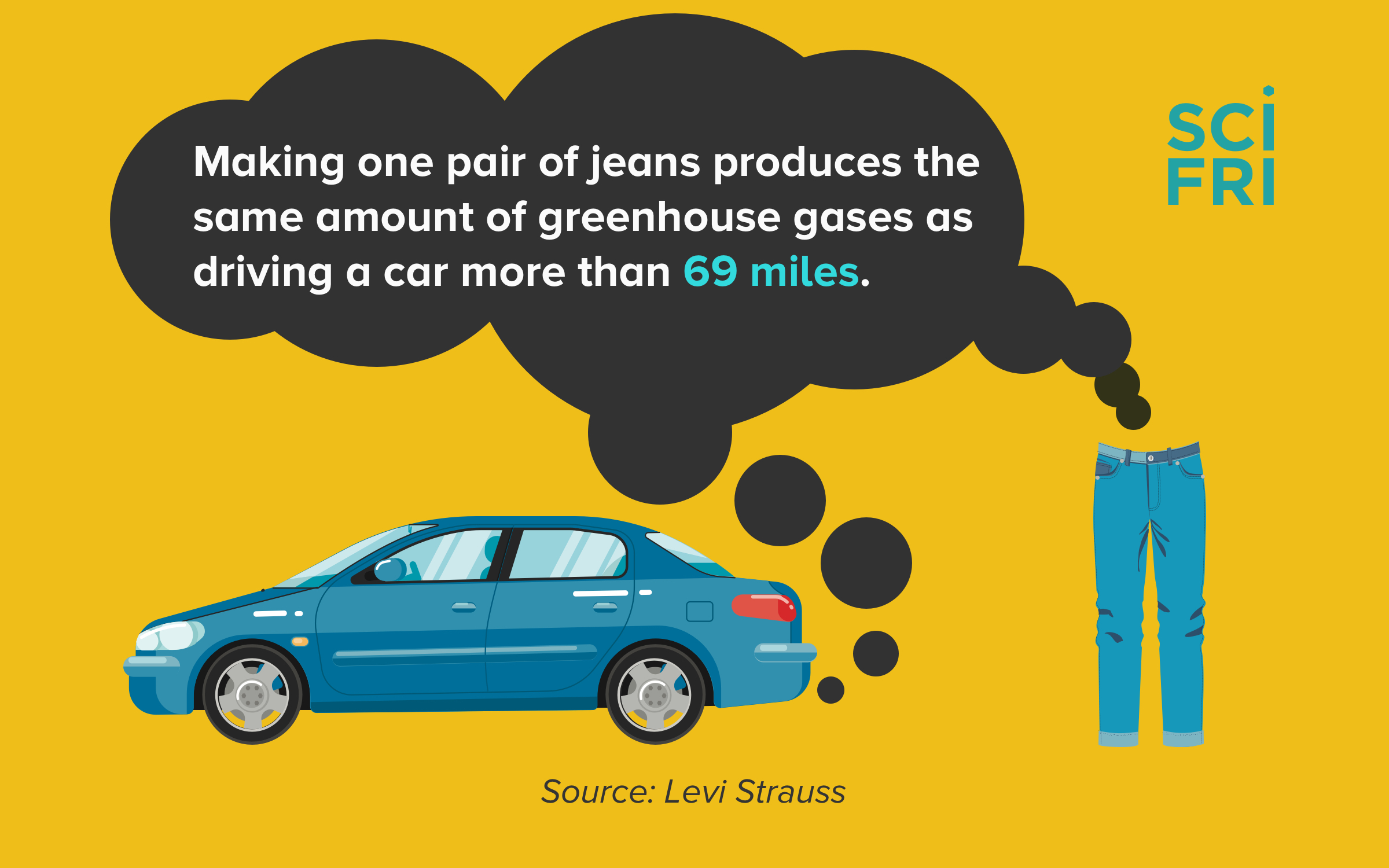

And if there’s one industry out there that knows something about trends, it’s the fashion industry. Long known for churning out cheap garments and burning through resources, some fashion labels like fast fashion giant H&M are now embracing sustainable fashion trends. But can this industry—which is responsible for 8% of global carbon emissions—really shed its wasteful business model in favor of one with a lower carbon footprint? Marc Bain, a fashion reporter at Quartz, Maxine Bédat from the New Standard Institute, and Linda Greer, global policy fellow with the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs talk with Ira about the industry’s effort to reduce its climate impact.

Richard from Madison: I try and buy at least half of my clothing secondhand from places like St. Vincent de Paul or Goodwill… Lara from Venice: When I buy clothing I try to make sure that it’s of a natural fiber, that it’s made locally, sometimes even fair trade or organic… David from North Carolina: One thing that I’m looking for is a few good pieces that I can wear over and over instead of hundreds of pieces in my closet… Tamara from Colorado: I consider the environmental impact of my personal clothing extremely conscientiously when I’m picking out clothes. I choose to visit thrift stores. My professional clothes, they’re work pants, they’re heavy-duty pants—I can’t factor in the environmental thoughts for that one, unfortunately.

Rethink how you shop for clothing. Instead of hitting the mall, buy used clothing. And if your local thrift shop isn’t cutting it, try an online used clothing retailer, like thredUP, The RealReal, Swap.com, or many others. Have a kiddo that seems to grow out of their clothes every two weeks? There are even online options for used baby and children’s clothing, like Owl Tree Kids.

And when you’re finished with your clothes, extend their lifetime by tossing them into the donate pile, or selling them on an app like Poshmark or Depop. Some brands, like Eileen Fisher, even have buy-back programs for lightly worn clothing.

Marc Bain is a fashion reporter for Quartz.

Maxine Bédat is the founder and executive director of the New Standard Institute.

Linda Greer is a senior global fellow at the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs in Beijing, China.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[CLOCK TICKING]

Continuing our coverage about the changing climate and the Degrees of Change series, it appears now– if you just heard our last segment– it seems like the whole world has suddenly been talking about climate change. All week you’ve been hearing our partners in the media report about climate change as part of the journalism initiative Covering Climate Now. And of course, today, students and people around the world are skipping school in support of taking action against climate change as part of the Global Youth climate strike.

Yes, it seems– right now you could say climate change is trending, as they say in the business. And if there’s one business out there that knows something about trends, it’s the fashion industry. Long known for marketing inexpensive garments, some fashion labels, like fast-fashion giant H&M, are now embracing sustainable fashion trends. Nike is reportedly grinding up old and surplus shoes to make running surfaces.

But can the fashion industry, which is responsible for 8% of global carbon emissions, can it retool to lower its carbon footprint? And whose responsibility is it to ensure clothing is sustainable? The clothing brands, the textile manufacturers, or you the consumer? Well, we posed that question to you on the Science Friday VoxPop app, and here’s some of what you had to say.

SPEAKER 1: It is absolutely the consumer’s responsibility to ensure that clothing is sustainable. The supplier’s motive lies in profit, and it is not always the most profitable to make sustainable clothing.

SPEAKER 2: Number one I think are the textile manufacturers, as they sort of lead the way, because if they are making the textiles that clothing brands are ordering, they should be sure that whatever they’re making won’t be harmful to our environment in any way.

SPEAKER 3: I think the ultimate responsibility for sustainable clothing rests with the clothing brands themselves. Tremendous profits are made simply by placing a designer label on any article of clothing. Brand companies should be required to reinvest a portion of these profits into developing products which can be easily recycled or repurposed by consumers.

IRA FLATOW: That was Anna from Las Vegas, Rachel from New York, and Kim from Pennsylvania. And that’s the topic we’ll be addressing today in the latest chapter of our Degrees of Change series. And here to talk about it with us is Marc Bain, fashion reporter for Quartz. Welcome to Science Friday.

MARC BAIN: Hi, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And Maxine Bédat, executive director of the New Standard. Thank you.

MAXINE BÉDAT: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: That’s the New Standard Institute.

MAXINE BÉDAT: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: Maxine, let me start with you. Where does the fashion industry get this reputation for wastefulness and environmental pollution?

MAXINE BÉDAT: Well, it gets this reputation from the facts, which is, as you had mentioned at the outset, that the apparel industry is responsible for 8% of the total global carbon footprint. And it is just projected to increase from there if we’re not changing anything. So the reputation is coming from the facts, and the facts are driven by several things. One is the fast-fashion players that you mentioned. We are wearing our clothing more. We’re buying clothes faster than we ever have before and getting rid of them just as fast. And so we have a system that’s really on overdrive producing in countries that have very low regulatory environments. So it’s combining, creating a real catastrophic mess for the environment.

IRA FLATOW: And Marc, I said in the intro that climate change is trendy. As a fashion reporter, do you see evidence of brands and following a trend responding to this?

MARC BAIN: Yeah, absolutely. I think it’s something that over the past several years, I’ve noticed, just become a bigger and bigger focus, among brands and also consumers. I do wonder just how much awareness there is out there among the average fashion consumer. But certainly, when you’re talking to brands, they’re saying that from what they hear from their consumers, that they’re concerned about sustainability and climate change. And brands are taking steps. You can debate whether they’re enough, but they are taking some steps to mitigate their impact.

IRA FLATOW: Let me just remind our listeners, you can give us a call, 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us at @SciFri. Are they are they voluntarily making these changes? And give me an idea of some of the changes that you were talking about.

MARC BAIN: Yeah, I think they are voluntarily making the changes just because there’s no greater authority telling them they have to do it.

IRA FLATOW: Consumers want this? Do they want this and that’s why they’re changing?

MARC BAIN: Yeah, I mean, arguably. I think there’s still some debate about whether consumers are willing to actually pay more for more sustainable products. There is some evidence that they will. I think brands, though, especially fashion brands are taking it upon themselves to get ahead of the backlash before it really happens. And you see that with some companies like H&M.

You see all sorts of climate pacts. Recently at the G7, carrying the luxury group that owns companies like Gucci and Saint Laurent, brought together all these different companies, like, major fashion and footwear companies to join this environmental pact and that sort of thing. That was all voluntary. It was at the behest of France’s president that they did it. But there’s no punishment if they don’t.

IRA FLATOW: Maxine, do you agree? Because what we’ve seen, and listening to people who are really in the forefront of the change and the marches today, there’s so many young people. I mean, people below the age of 25 who were out there. And these would seem to be the prime audience, the prime consumers that the fashion people would be looking at.

MAXINE BÉDAT: I think it’s a little tricky with the fashion space when you say that sustainability is trending. Because one could paint that as, isn’t it great the fashion companies are jumping on board and they are looking to reduce their carbon footprint? But we’re not necessarily seeing that.

I’ve seen on presentations, and I’m sure these are presentations from fashion companies all around where it’s polka dot is in, leopard print is in, and oh, sustainability is in. What is that sustainable product we can push out there so that people are buying more? That is, of course, antithetical to really what is a major problem and driver of the challenge and of the carbon footprint, which is just how much is being produced.

So, yeah, I think we’re seeing, as more and more people are finding out about what the problem is with regard to fashion, more consumers and the young generation are interested. But it’s whether these pacts, and promises, and quote, commitments that brands are making, whether they are actually scientifically leading to any change.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s get into the science of consumerism and recycling here. Where does the great waste come in the production of fast fashion or any fashion?

MAXINE BÉDAT: Yeah, so I think the thing for listeners to keep in mind– and we’re not so aware of, I think especially in the United States, because while we still see farms we don’t see much manufacturing. And today less than 2% of our clothing is actually produced in the United States. So we don’t really see these factories. And it isn’t so visceral the way it was in the ’60s when clothing was manufactured here.

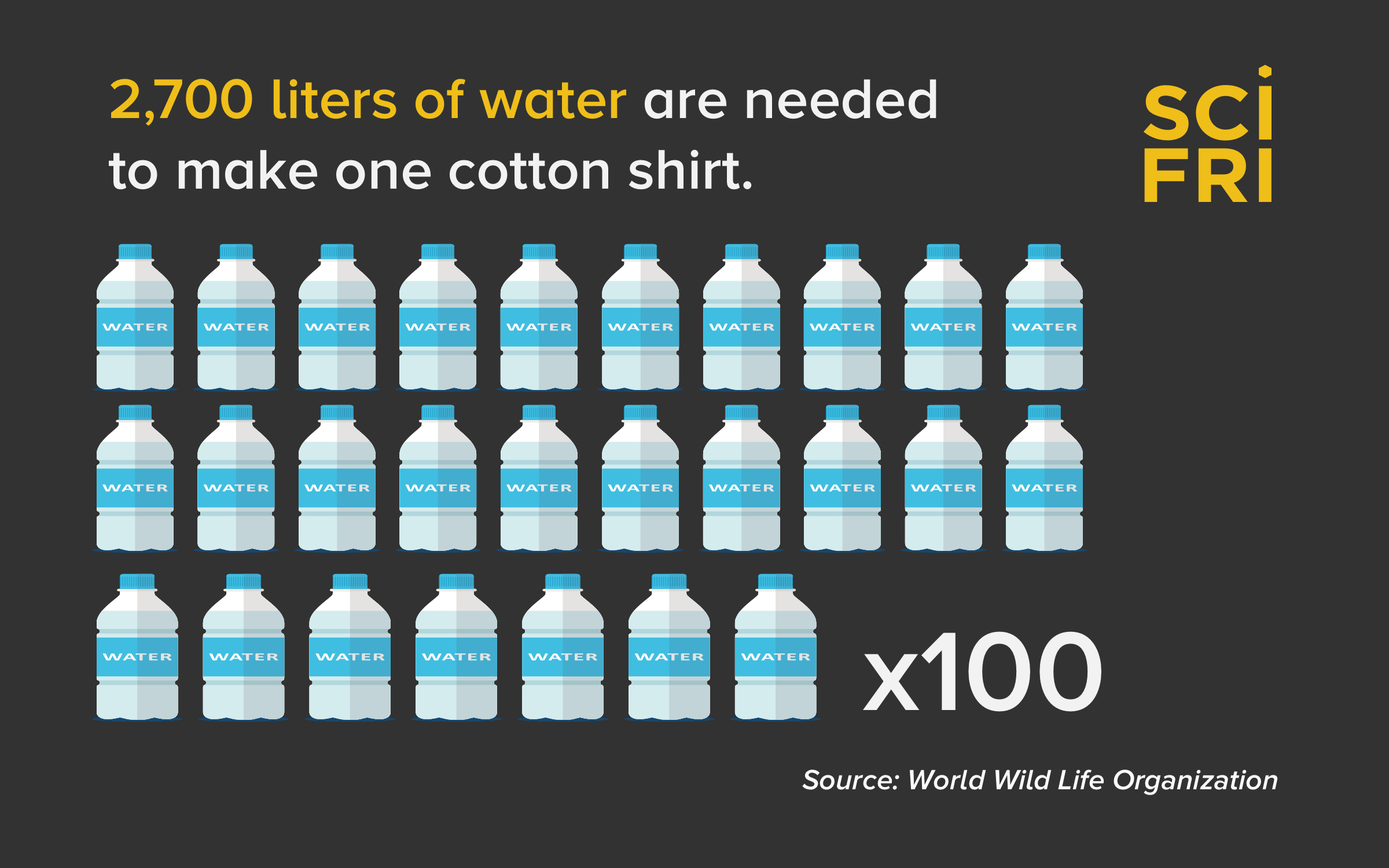

But if we think about just how clothing is produced, you either are starting with an oil rig or a farm. You’re having to actually create the fibers. Those fibers are then shipped probably halfway around the world. Those fibers have to be spun. They have to be woven. Then they’re shipped probably into another country to then be cut and sewn. And within that are hundreds of steps.

And it’s not that a cotton ball magically becomes the shirt that you’re wearing today. That is an incredibly energy-intensive process that requires a lot of hot water. And to create a lot of hot water requires a lot of heat. And so the bulk of your environmental footprint is actually in that textile creation process.

IRA FLATOW: Is there some way to figure out which clothing label is more environmentally aware than any other? Is there a way to figure that out?

MAXINE BÉDAT: There is, it’s called an LCA life cycle assessment, which is a tool that has been used in other industries as well. And should be used more, I would argue, in this industry. And that is a way to actually understand, what is the carbon footprint from the very beginning to the very end of the cycle when it ends up in a landfill.

IRA FLATOW: And we spoke with Shona Quinn, sustainability leader for women’s clothing brand Eileen Fisher, about what they found when they looked at their carbon impact.

SHONA QUINN(ON PHONE): There aren’t a lot of quick fixes when it comes to sustainability in the apparel sector or the fashion sector. And because, as simple as a t-shirt seems, the supply chain is quite complex. And it passes through a lot of different hands, many times a lot of different countries.

So more recently for us, we did a carbon footprint assessment. And we looked at it from the raw material all the way up to our distribution center. And within the supply chain, what we found was a little bit over a third of the impact is happening at the raw materials stage.

Another over-a-third of it is happening at the industrial processing level. So that’s the cutting and the sewing, the weaving, the knitting, the dyeing, the spinning. And then the last piece, for us, of about 25% is around the shipping. And the air versus sea and getting the products from the farm all the way to the distribution center.

IRA FLATOW: Marc, can’t brands use the power of the purse then to put pressure on these manufacturers?

MARC BAIN: Yes, they can. It’s a bit complicated, though, because the situation that’s been created, the whole system that’s set up is arguably a result of the brands and the pressures that they’ve created to produce more stuff at cheaper prices. And in part, the brands are doing that because the more volume they sell, the more money they make. And so you have this inherent tension between selling more clothing, which is going to give you more profits, and your footprint, which the more you sell the bigger that footprint’s going to become.

Brands can use their leverage to push on the textile factories and their suppliers and that sort of thing. But do they? Probably not enough, at least not from what I’ve seen.

IRA FLATOW: I want to bring on another guest into the discussion. Linda Greer is a senior global fellow at the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, a leading Chinese environmental nonprofit. Welcome to Science Friday.

LINDA GREER: Hi, Ira. How are you?

IRA FLATOW: Fine, thank you for joining us.

LINDA GREER: Sure.

IRA FLATOW: What is the relationship between the clothing brand and the textile manufacturers in China? Are they owned by the brands or are they separate?

LINDA GREER: Yeah, for the most part they’re separate. So the brands shop around for suppliers that will give them the best price and the quality that they’re looking for. And there’s usually a tense relationship between the brand and the manufacturers. The manufacturers feel like although they hear from the brands that they are interested in sustainability they don’t really get more business for it, that the people from the brands talking to them about the need to reduce their carbon footprint are not the same people from the brands that are placing the orders. And so there’s quite a bit of frustration that there is no business return so to speak, for good behavior with regards to reducing their footprint.

IRA FLATOW: So are the textile manufacturers in China open to making the necessary improvements?

LINDA GREER: Well, their hand is being forced at the moment, actually. Because the Chinese government has begun a serious crackdown, both on their pollution and on their carbon through the way that they get their electricity, et cetera. As I’m sure all the listeners know, the pollution problems in China are so egregious that the central government has had to take radical action to try to reduce the footprint there. And as a result, the factories are feeling quite a bit of pressure from inspections and enforcement by the Chinese government, which is something that is very, very new to them, only a few years old.

And something which has also caught the attention of the brands, because they definitely want a secure and risk-free supply chain. So they don’t want to see factories being closed suddenly as a result of any reason, including their environmental performance. So times are changing in China quite a bit with regards to pollution.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. I’m Ira Flatow, this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking about the fashion industry and global warming, climate change. Let’s see if we have– we have a couple of interesting tweets coming. Can you talk about whether the new online resale markets like ThreadUp and Poshmark are helping the cause or driving the buy-sell fast market further?

MAXINE BÉDAT: So I’m quite excited by the resale market, which is growing remarkably. Poshmark came out that the resale market is going growing at 21 times the rate of traditional retail. I think that is something, just as a paradigm shift, is really exciting to see that even from when I was younger, buying used clothes maybe was looked down upon. And now it’s something that is really just very readily accepted.

And I think it’s kind of those paradigm shifts that we really need to think about, that used clothes and wearing your clothes more is something to be excited and celebrated. So I see that as something positive, something we should look into with the data, certainly. But in terms of user behavior, something that’s really exciting.

IRA FLATOW: I want to ask you, before we go to the break, the same question that we posed to our listeners earlier. Who’s responsibility is it to make sure fashion is sustainable? Is it the brands, the consumer, or the textile manufacturers? Linda, let me begin with you.

LINDA GREER: I feel strongly that the responsibility lies with the brands. And here’s the way that I see it. Do drug companies say to us they’re going to wait to hear from their customers before they make a drug that’s safe and effective? No, they just know as a responsible company that’s what they’re supposed to do. And I think it’s a basic business responsibility for a company to take control of their environmental footprint given the urgency of the situation that we have.

So I lay the responsibility fully on the brands. They also conveniently happen to be the party with the leverage to make it happen. Because if they did prefer factories who were lowering their footprint with more business then we would have it going on. But they’re really the rate limiting step at the moment.

IRA FLATOW: Maxine?

MAXINE BÉDAT: Yeah, I mean, I would agree with Linda on that point. What I would add is, brands are certainly directly most responsible and most able to do it. But it’s the consumer that’s going to drive the brand to do that. And so it’s us, the consumers who have to demand change and demand that shift so there is that pressure on the companies to make those transitions.

IRA FLATOW: What do you say, Marc?

MARC BAIN: I agree with all those points. I think the brands are really the ones who are kind of driving the system. So I think the bulk of the responsibility does lie with them. You can argue that everyone has their own little piece of that responsibility. But I think the brands are really the ones with most of it. I would also add that you can argue that government should be involved and should be helping to regulate this stuff. There’s a reason that drug companies are regulated. And you could argue it’s a similar sort of point.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, the environment is getting to be life-threatening now. We’re going to take a break and come back and talk lots more about the fashion industry and climate change with Marc Bain, Maxine Bedat, and Linda Greer. Our number is 844-724-8255, you can also tweet us at @SciFri. Stay with us, we’ll be right back. This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We’re going to continue talking this hour about the fashion industry’s carbon footprint and how brands are responding to consumer pressure to be more sustainable. Let’s turn now to some of the new technologies that are trying to change the fashion industry’s supply chain. So instead of garments made from fresh cotton and polyester fibers, your new clothes, so to speak, can now be made from the recycled fibers of old clothes. Here’s what I’m talking about, Stacy Flynn is the founder and CEO of Evrnu, one of these new technology companies recycling old clothes. And this is how she describes the process.

STACY FLYNN(ON PHONE): Evrnu is is a technology R&D company. We have six different technologies in development right now. And the first technology we have breaks down cotton garment waste. So basically we take post-consumer cotton garment waste and we take it from a solid, we liquefy it, and then once it’s in its liquid form we can convert it back into a solid form kind of like when you make pasta. You can make pasta once you have a dough, you can push it through a pasta maker and you can make linguine, or Angel hair, or lasagna, whatever you want once it’s in that form.

Our research is all done on post-consumer garment waste. These are the things that we wear, that we are donating potentially, or throwing in the garbage. Back in 2012, US consumers are throwing away 80% of their textiles directly into the garbage can every year. And at that time, the number was probably 12 million tons of garment waste in the US.

Today US consumers are still disposing of 80% of their textiles directly into the garbage. But the number has gone up to closer to 21, 22 million tons of garment waste per year. One of the things that we’ve been studying is by preventing textiles from entering landfills, because if a garment enters a landfill it creates methane. Methane is over 20 times more powerful than CO2. So if we are designing products that never have to enter a landfill, then we’ve got a massive changing of the tides.

IRA FLATOW: That’s Stacy Flynn, founder and CEO of Evrnu. I’d like to bring in my guests to get their thoughts on this. Still with me are Marc Bain fashion, reporter for Quartz, Maxine Bedat, executive director of the New Standard Institute, Linda Greer senior global fellow at the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs based in Beijing. Let’s talk about what we just heard. Marc, you covered companies like Evrnu in your reporting. What makes recycling textiles such a popular idea now?

MARC BAIN: Well, the volume of waste that she talked about. Imagine if you could take that waste, instead of putting it into a landfill, chop it down back into raw material and turn it back into new clothing you could sell. That’s a really powerful idea. However, we are very far from any point where that’s an actual scalable commercial technology. So it’s a really important idea with a lot of potential. It’s great that we’re researching this. But you can’t, at this point, really buy clothing made out of recycled clothing yet.

IRA FLATOW: And there’s no place to recycle it, if you just want to recycle the clothing, right? Unless you bring it to Goodwill or somebody else wearing.

MARC BAIN: There are all sorts of reasons why we’re still far from scalable textile recycling, and that’s just one of the reasons. We don’t have the infrastructure set up to collect everything. There are also issues with fiber blends, which is something that Evrnu is working on. Most of the recycling we can do right now, it’s either got to be pure polyester or pure cotton. The methods we have are not great for turning that stuff back into new clothing, if you have a blend of polyester and cotton which is a great deal of clothing today is. Again, we can’t really do that much with it at this point.

MAXINE BÉDAT: And I would just add to the conversation, there’s so many misconceptions about what happens to our clothing when we get rid of it. And often it is just said, well, donate it and kind of leave it at that. But there’s a whole underworld of that donation, which runs very parallel and similar to what happens when you bring your clothing back with the exception of Eileen Fisher, but when you are giving your clothing back to these give back programs of brands. And that is a big percentage of them are being sorted, shipped, and sold in the developing world.

And I was just in Ghana in July visiting one of these secondhand markets where our donated clothes that don’t end up getting sold end up. And I followed the clothing there, which about half of that never actually gets bought and is just going into landfill in Ghana. So we end up actually just exporting the clothing that we don’t want anymore to the developing world. When I was in Ghana visiting the landfills where the clothing was ending up, it was actually on fire because the landfill was so over-flooded with clothing that the measures in place to protect it were not there.

And so I was speaking to one of the sellers at the second-hand market and he said, I just don’t understand you Americans. You drive around, in his perception, in all electric cars but then you’re wearing all these clothing that end up here and we end up burning them. So I don’t understand the math. To

Which I said, well we don’t know that part of the story. And I think it’s important for people to realize that we need to invest in these big technology solutions. But we also just need to be aware of what happens to our clothing. And I think that will help us all think about that next purchase.

IRA FLATOW: Linda, you’ve expressed doubts about this concept of what’s called circular fashion, haven’t you?

LINDA GREER: Yes, I have. And I have to say, I mean, I’m a fan of Evrnu. I’ve followed them pretty closely. And I think they are in some ways unique in that they really are trying to do the lifecycle assessment that we talked about earlier and sort of follow the pounds around, which many, many innovations are not doing. So from the glass being half-full, I would say that’s a technology well worth following.

On the other hand, I agree both with Marc that what we really have here is a problem of volume of sales and that these technologies are not going to come into being fast enough to rescue us from that. I think listeners ought to take stock that although it’s true that recycled fiber would save the impact of growing the fiber or the crude oil that went into making the synthetic fiber all the rest of the impacts going into making your clothing, which are considerable in terms of scouring the fabric, and bleaching it, and then dyeing it, and then adding softening chemicals, and all of this happening in very hot and high-pressure environments in a factory, all of those processes will still go on with a circular economy.

Because the fiber itself will not be a virgin fiber, which is a plus. But the rest of it is still there for us. And the environmental impacts of that manufacturing, of those industrial processes, are larger than other pieces of the puzzle. So they’re really something that we have to keep in mind. So, you know, I don’t have an objection to it. I just object to seeing it as a silver bullet.

IRA FLATOW: I’m going to take a phone call. A lot of people are calling in, 844-724-8255. Let’s go to Stockton, California with Tyler. Hi, Tyler.

TYLER: Hi, how we doing today?

IRA FLATOW: Hi, go ahead, please.

TYLER: I was wondering about a lot of these, like, fashion as a service companies that are popping up. I know Nordstrom has partnered with one of them, where you essentially rent clothing and then return it. But I’m wondering, is that a net positive or a net negative given that there’s probably shipping and other infrastructure in between those steps?

IRA FLATOW: Linda, Maxine?

LINDA GREER: Yeah, I think it’s a net positive. I mean, going back over what Maxine said earlier, which I strongly agree with, it’s on a parallel track in my mind with buying vintage. The less throughput we can have in this industry, the better. Because all of these innovations are just chipping away at what is an enormous carbon and pollution footprint. And so anything multiplied by a million pieces is a large number. So if we could reduce the number of pieces that are being manufactured by people either renting or buying vintage, I think that’s the single most promising immediate step we can take to lower the footprint of this industry.

IRA FLATOW: Maxine?

MAXINE BÉDAT: Yeah, I would agree with Linda. I would add that for these companies that are growing these rental companies or rental initiatives that are growing and receiving so much interest, I think all of that is great. I think what the companies could do, we keep mentioning this term lifecycle assessment, is do the LCA work so that they can really prove just how beneficial it is. I think that if we could all be armed with that type of data we could not just know intuitively that it’s right, but statistically that it’s right too.

IRA FLATOW: You know, our clothing labels come with washing, material, and instructions, and drying, and whatever. Could we make clothing that rates how environmentally big a footprint this thing you bought is?

MARC BAIN: In theory you could. You would have to have somebody actually assessing . That The way things are at this point, you would probably be relying on the brands to tell you how sustainable they are and not an independent third party that’s going to be brutally honest. And so there’s also all sorts of factors that go into it. It would be extraordinarily difficult to do that.

Unfortunately, one of the things that I feel like we keep coming back to is, there really are no great silver bullet solutions. One thing you see a lot from brands is they launch new sustainable collections. That’s great, but what about their main collection and all the other stuff they’re producing? When we talk about how to solve the problem, the solution over and over is to actually just produce less. And nobody seems willing, at this point, to really commit to that, with a few exceptions.

IRA FLATOW: But if you could make it a competition among companies, competitive that you get to be known as a more sustainable corporation, people might want to buy your product more would? Would they not, Maxine?

MAXINE BÉDAT: Yeah, I think absolutely. And the work that we’re doing at the New Standard institute is trying to ask the brands and get consumers to ask brands to disclose what is their carbon footprint, to set targets for what they’re going to do to achieve reductions. And ultimately to scientifically know that we are moving in the right direction, not as Marc said just producing yet another, quote, sustainable collection.

I think going back to that idea of having a label, it’s not impossible. We could put the LCA scores. I think goes back, Marc, to what you were mentioning earlier, which is having regulations. I think if we really just take a step back and look at where we are in the clothing industry with where we were in the food industry maybe two decades ago, that’s where the clothing industry is.

We know there’s this issue. Consumers are just beginning to see that this is a problem. So I am hopeful that with more citizen consumer engagement with this issue that we really can start to put the right type of pressures on brands. And then ultimately, hopefully that this is something that is just regulated in the rules of the game. And then–

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking about environmentally responsible clothing and fashion. Let me get a tweet in here, because we get this tweet, not from the same person, all the time wherever we talk about sustainability. And it goes like, let’s hope hemp is discussed. It’s one of the most environmentally friendly fabrics along with regenerative wool, plus all kinds of things. He goes on. But what about hemp? Linda or Maxine, does it offer a solution to this problem? Or I’ll ask Marc, what do you think? Who wants to jump in?

LINDA GREER: Hemp is a good fiber. It is easier to grow than cotton and it can be grown in places that have less problems with water scarcity. So I don’t think there’s any big problem with hemp. Is hemp a big solution? I don’t think, really. And that is, again, because first of all, we can’t ignore the majority of the footprint, which is from the industrial processing, shipping, and other things.

And also just because, again, getting it up to scale around the world would be challenging. But it’s definitely another little chink that we could put into the system that would reduce the use of cotton, which is itself a very thirsty and pesticide-intensive crop to grow.

IRA FLATOW: I want to go back to one more clip from our listeners, if they think about this sustainability when they make their clothing purchases. And this is what you had to say.

RICHARD: I try and buy at least half of my clothing second-hand from places like St. Vincent de Paul or Goodwill.

LARA: When I buy clothing I try to make sure that it’s of a natural fiber, that it’s made locally, sometimes even fair trade or organic.

DAVID: One thing I’m looking for is a few good pieces that I can wear over and over instead of hundreds of pieces in my closet.

TAMARA: I consider the environmental impact of my personal clothing extremely conscientiously when I’m picking out clothes. I choose to visit thrift stores. My professional clothes, they’re work pants. They’re heavy duty pants, I can’t factor in the environmental thoughts for that one, unfortunately.

IRA FLATOW: That was Richard from Madison, Lara from Venice, and David from North Carolina, Tamara from Colorado. It seems to be on the minds of people.

MAXINE BÉDAT: Yeah, it’s good to hear.

IRA FLATOW: So that is a hopeful note, Maxine.

MAXINE BÉDAT: Definitely. I came at this as a lawyer in the beginning of things. And I consumed a lot of fast fashion and loved it. And it was only from discovering just what was happening behind the scenes in the industry that I changed. So I have to assume I’m just like a regular person. And that as people are being exposed to what is happening behind the scenes that the natural reaction is to say, whoa, what can I do?

And I think that’s also something that is, when we talk about the climate conversation, fashion is often dismissed. And I wonder why. Often I wonder, is it because it’s driven by a lot of women and that can get dismissed? Is it that it’s an industry that is far away and so we don’t think about carbon flows and global carbon flows? We just think about the solar panels that we can put on our house. And so yeah, I’m hopeful.

IRA FLATOW: You’re hoping we’re talking about it more.

MAXINE BÉDAT: Exactly, people are talking about it more. We’re talking about it today.

IRA FLATOW: We are.

MAXINE BÉDAT: And I think that that’s a very exciting progress. And people are beginning to see. And it’s a sector that is driven by consumers. And so I think that’s an exciting area for change within the climate conversation.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’re excited to start this conversation with Marc Bain, fashion reporter for Quartz, Maxine Bedat. Executive director of the New Standard Institute, Linda Greer, senior global fellow at the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs based in Beijing. Thank you all for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Andrea Corona is a science writer and Science Friday’s fall 2019 digital intern. Her favorite conversations to have are about tiny houses, earth-ships, and the microbiome.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.