How Serena Williams Destroyed A Drone With A Tennis Ball

Tennis legend Serena Williams hits the court to face off with a drone in this excerpt from Randall Munroe’s “How To.”

The following is an excerpt of How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems by Randall Munroe.

A wedding-photography drone is buzzing around above you. You don’t know what it’s doing there and you want it to stop.

A wedding-photography drone is buzzing around above you. You don’t know what it’s doing there and you want it to stop.

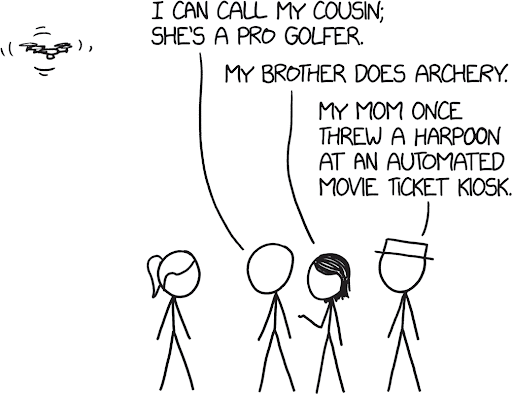

Let’s assume you don’t have any kind of sophisticated anti-drone equipment, like net launchers, shotguns, radio jammers, mist nets, counter-drone drones, or other such specialized gear.

If you do have a very well-trained bird of prey, you may think it’s a good idea to send it after the drone.

How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems

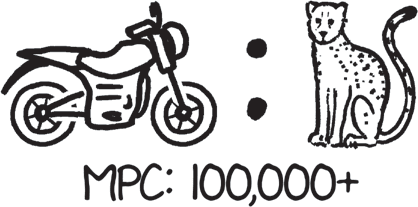

Every now and then, videos circulate around the internet showing trained birds of prey snatching drones out of the sky. This is a concept we find instinctively satisfying, but any plan that calls for countering rogue machines by training animals to hurl themselves at them is probably a bad one. We wouldn’t enforce speed limits by training cheetahs to leap onto motorcycles. It would be cruel and dangerous to the cheetahs, and besides, there are a lot more motorcycles than there are cheetahs. Earth’s motorcycle : cheetah ratio (MpC) has never been precisely calculated, but it’s probably several hundred thousand.

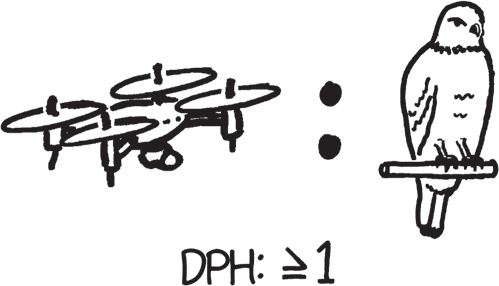

Similarly, there are certainly more drones in the world than birds of prey—and new drones are being produced a lot faster than new birds of prey. Earth’s drone : hawk ratio is harder to estimate than its MpC, but it’s almost certainly greater than 1.

If falcons are a bad idea, what else might you use?

Drones are up in the air, so you want to send an object flying through the air. Humans send objects flying through the air all the time in the world of sports—see chapter 10: How to Throw Things for instructions.

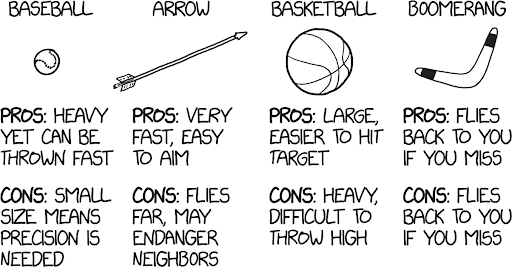

Let’s suppose you have a garage full of sports equipment—baseballs, tennis rackets, lawn darts,1 you name it. Which sport’s projectiles would work best for hitting a drone? And who would make the best anti-drone guard? A baseball pitcher? A basketball player? A tennis player? A golfer? Someone else?

There are a few factors to consider—accuracy, weight, range, and projectile size.

A lot of drones are pretty fragile, so let’s assume for the moment that as long as you can hit it, you’ll cause it to crash. (This has certainly been my experience.)

For the purpose of approximate comparisons, we’ll use a simple number to rate the accuracy of projectiles across different sports, representing the ratio of range to error. If you throw a ball at a target 10 feet away, and you miss by an average of 2 feet, then you have an accuracy ratio of 10 divided by 2, or 5.

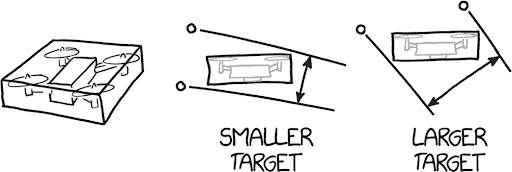

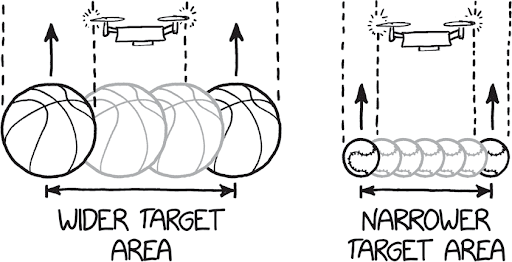

The body of a medium-size drone—like the DJI Mavic Pro—has a “target area” about a foot across, meaning we can miss the center of the drone by 6 inches in either direction. If it’s hovering 40 feet away, we’ll need an accuracy ratio of 80 to be likely to hit it—or somewhat less if the projectile is larger, since that gives us more room for error.

Shots in which the projectile travels in a high arc, like in basketball or golf, gain additional accuracy, since the drone’s wide and flat shape presents more of a target. And large projectiles, like footballs and basketballs, have more margin of error.

Here are some estimated accuracy ratios for various athletes, based on competition play, exhibitions, or scientific studies in which athletes tried to hit targets.

| Athlete | Estimated Accuracy Ratio | Attempts required to hit DJI Mavic Pro at 40 feet | Based on |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soccer Kicker | 21 | 13 | Study of 20 experienced Australian players |

| Placekicker | 23 | 15 | NFL Kickers in the late 2010s |

| Recreational hockey player | 24 | 35 | 25 recreational and university hockey players |

| Basketball (Shaquille O’Neal) | 36 | 4 | NBA free throw percentage |

| Golf drive/chip | 40 | 6 2 | PGA drive accuracy stats |

| Basketball (Steph Curry) | 63 | 2 | NBA free throw percentage |

| NHL All-Star | 50 | 9 | NHL accuracy shooting |

| NFL QB passing | 70 | 4 | Pro Bowl precision passing typical score3 |

| High school pitcher | 72 | 3 | Study of 8 Japanese high school pitchers |

| Professional pitcher | 100 | 2 | Study of 8 Japanese high school pitchers |

| Darts champion | 200-450 | 1 4 | PDC analysis of Michael van Gerwen |

| Olympic archer | 2,800 | 1 | 2016 Korean men’s archery team |

Clearly, archers are the best choice, if you can find one. Their combination of extreme precision and long range would make them ideal defenders. Pitchers would also be a great choice—and a baseball would probably do a lot of damage. Basketball players make up for their lower accuracy with a large projectile and efficient arcing shot. Hockey players, golfers, and kickers are all probably less than ideal choices.

I was curious to test this in the real world, and one sport I couldn’t find good data on was tennis. I found some studies of tennis pro accuracy, but they involved hitting targets marked on the court, rather than in the air.

So I reached out to Serena Williams.

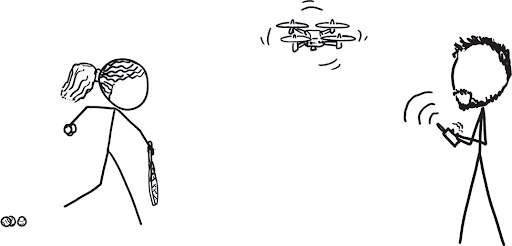

To my pleasant surprise, she was happy to help out. Her husband, Alexis, offered a sacrificial drone, a DJI Mavic Pro 2 with a broken camera. They headed out to her practice court to see how effective the world’s best tennis player would be at fending off a robot invasion.

The few studies I could find suggested tennis players would score relatively low compared to athletes who threw projectiles—more like kickers than pitchers. My tentative guess was that a champion player would have an accuracy ratio around 50 when serving, and take 5-7 tries to hit a drone from 40 feet. (Would a tennis ball even knock down a drone? Maybe it would just ricochet off and cause the drone to wobble! I had so many questions.)

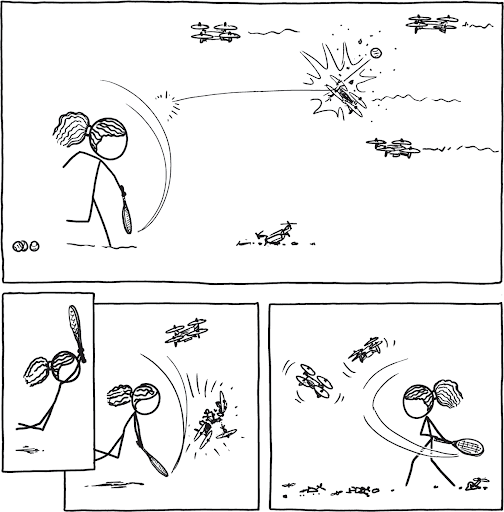

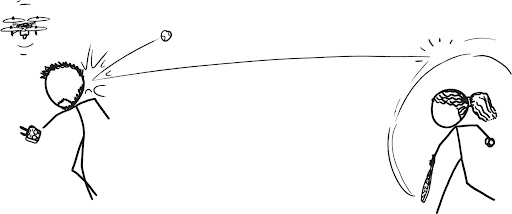

Alexis flew the drone over the net and hovered there, while Serena served from the baseline.

Her first serve went low. The second zipped past the drone to one side.

The third serve scored a direct hit on one of the propellers. The drone spun, momentarily seemed like it might stay in the air, then flipped over and smashed into the court. Serena started laughing as Alexis walked over to investigate the crash site, where the drone lay on the court near several propeller fragments.

I had expected a tennis pro would be able to hit the drone in five to seven tries; she got it in three.

Even though it’s just a machine, a drone lying on the ground seems oddly tragic.

“I felt really bad hurting him,” Serena said, after the pieces had been collected. “Poor little guy.”

I couldn’t help but wonder: Is it wrong to hit a drone with a tennis ball?

I decided to ask an expert. I contacted Dr. Kate Darling, robot ethicist at the MIT Media Lab, and asked her if it’s wrong to hit tennis balls at a drone for fun.

She said, “The drone won’t care, but other people might.” She pointed out that while our robots obviously don’t have feelings, we humans do. “We tend to treat robots like they’re alive, even though we know they’re just machines. So you might want to think twice about violence towards robots as their design gets more lifelike; it could start to make people uncomfortable.”

That made sense, but on the other hand, should we really be making ourselves so vulnerable?

“If you’re trying to punish the robot,” she said, “you’re barking up the wrong tree.”

She has a point. It’s not the robots we need to worry about, it’s the people controlling them.

If you want to bring down a drone, perhaps you should consider a different target.

1. For those who weren’t around in the 1980s, lawn darts were big heavy plastic darts with metal tips, similar to medieval weapons, which were sold to children as part of a game that involved throwing the darts high into the air. They were eventu- ally banned in the United States for reasons that seem pretty obvious in retrospect.

2. This is for a very accurate long drive. Accuracy for shorter-range chips may be higher.

3. Quarterback Drew Brees, on the show Sport Science, threw a football at an archery target 20 yards away, hitting the bulls-eye ten times out of ten. This suggests that under those circumstances, his accuracy ratio is somewhere above 700—better than a darts champion.

4. If they could keep their accuracy at that long range.

Excerpted from How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems by Randall Munroe. Copyright © 2019 by Randall Munroe. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Randall Munroe is a comic artist, creator of xkcd.com, and author of Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015) and What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014). He’s based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.