Celebrating Apollo’s ‘Giant Leap’

33:03 minutes

This story is part of our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. View the rest of our special coverage here.

This story is part of our celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. View the rest of our special coverage here.

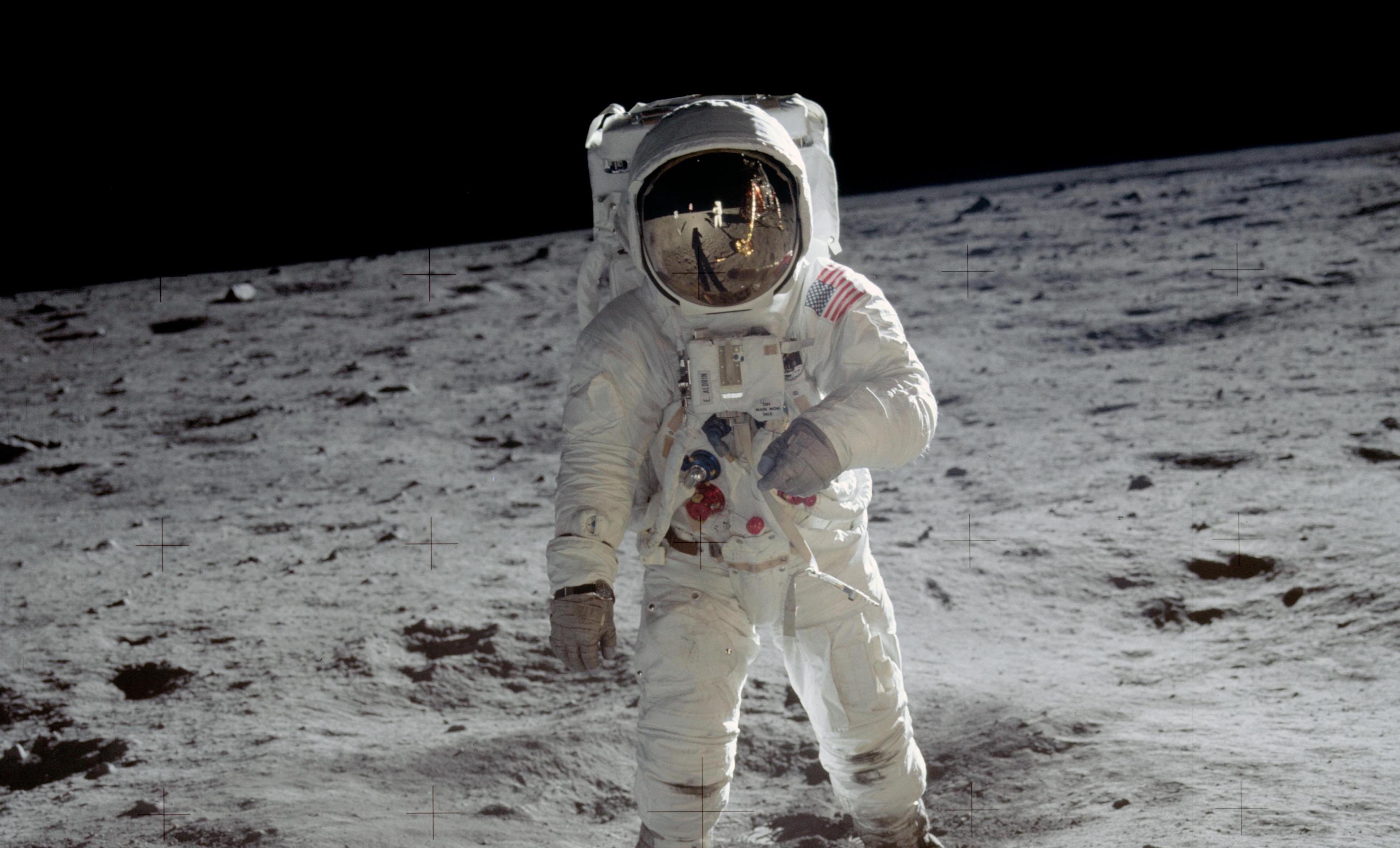

July 20, 1969 was a day that changed us forever—the first time humans left footprints on another world. In this segment, Ira Flatow and space historian Andy Chaikin celebrate that history and examine the legacy of the Apollo program.

Apollo ushered in a new age of scientific discovery, with lunar samples that unlocked the history of how the moon and the solar system formed. It accelerated the development of new technologies, like the integrated circuit. And most of all, says Chaikin, it taught us how to work together, to achieve seemingly impossible goals.

We’ve been collecting your thoughts on the legacy of Apollo on the SciFri VoxPop app all week. Here’s what you had to say, kicking off with Bill in Portland, Oregon.

Transcript: Bill: I believe the Apollo program inspired a nation and showed what we could accomplish. Linda: Without the things that were happening back in 1969, with the Vietnam War, that was a great, positive thing for the world and for people to look forward to. Rich: It helped, at least, spur the development of commercial computers. David: I am recording this on a device who existence is a direct result from NASA’s need for tiny electronics. Edna: Heightened curiosity about science. Tom: Freeze-dried foods. Ronnie: I think the Apollo program’s single biggest contribution to society was the photograph of Earth. Tom: That single picture let us know how fragile our planet is, how thin that little atmosphere that envelops the planet is. And what a huge universe we are existing in.

That was Linda in Wisconsin; Rich in BNA; David in Creedmore; Edna in Pennsylvania; Tom in Oakland; Ronnie in Pennsylvania; and Tom in Arkansas.

We’ll also take a look at what comes next for NASA’s historic launchpads. Science Friday producers Alexa Lim and Daniel Peterschmidt went to NASA Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida a few months ago. They got to see how the space agency is upgrading some of its storied launchpads—and leaving others behind.

NASA is currently updating the Apollo-era launchpad 39B, which has seen launches ranging from Apollo to the Space Shuttle. Now, they’re making sure its ready for the biggest rocket ever built: the Space Launch System, which NASA hopes will ferry humans to the moon and deep space beyond.

Meanwhile, less than 10 miles away is Launch Complex 34, the site of the Apollo 1 disaster. It’s officially abandoned—and it shows. The half-century old launchpad resembles a modern-day ruin. Rust is everywhere and large chunks of metal are missing. While it isn’t being physically restored, it is being digitally preserved, thanks to a team at University of South Florida led by Lori Collins. Using extremely precise 3D laser-scanning, they’re preserving the complex and many others like it for future generations.

You can listen to the trip below and read much more about how NASA is also protecting its active launchpads from rising sea levels.

Andrew Chaikin is a science journalist and space historian, and author of A Man on the Moon (Viking, 1994) and Voices From the Moon: Apollo Astronauts Describe Their Lunar Experiences.

Lori Collins is a Research Associate Professor and Co-Director of the University of South Florida Library’s Digital Heritage & Humanities Collections at the University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida.

Regina Spellman is a Senior Project Manager at NASA.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, we’re kicking off our summer book club with a celebration of bird brains. So stay tuned for the book announcement and how to play along.

But first, we’re commemorating the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 and that moment in July, 1969 that brought people all over the world together to witness one small step for a man and the end of one giant political race to the moon’s surface.

If you have a memory to share about Apollo 11 or thoughts on the legacy of the moon program– what was the Apollo program’s biggest achievement or maybe its biggest shortcoming? Give us a call, 844-724-8255, 844-724-8255. Or of course you can tweet us @SciFri.

And we’ve been collecting your thoughts on the new Sci Fri VoxPop app all week. You can find the Sci Fri VoxPop wherever you get your apps to join in. And here’s what you had to say about the legacy of Apollo, kicking off with Bill in Portland, Oregon.

BILL: I believe that the Apollo program inspired a nation and showed what we could accomplish.

LINDA: With all the things that were happening back in 1969 with the Vietnam War, that was a great positive thing for the world and for people to look forward to.

RICH: Helped at least spur the commercial development of computers.

DAVID: I am recording this on a device whose existence is a direct result from NASA’s need for tiny electronics.

EDNA: Heightened curiosity about science.

RONNIE: Freeze dried foods.

TOM: I think the Apollo program’s single biggest contribution to society was the photograph of Earth.

TOM: That single picture let us know how fragile our planet is, how thin that little atmosphere that envelops the planet is and what a huge universe. We are existing in.

Along with Bill, that was Linda in Wisconsin, Rich in Tennessee, David in North Carolina, Edna and Ronnie in Pennsylvania, Tom in Arkansas, and Tom in California sharing their thoughts on Science Friday VoxPop app. And you can go ahead and download it and share your thoughts, Sci Fri VoxPop with a V, Sci Fri VoxPop.

Let me introduce my guest for the hour, our guide to all things Apollo, Andy Chaikin. He’s a space historian who’s written extensively about the Apollo program, including the book, A Man on the Moon. He’s also a visiting instructor at NASA, teaching the human behavior elements of success in spaceflight. He joins us from Northeast Public Radio in Albany. Good to talk to you again, Andy. It’s been a while.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Yes, Ira. Nice to be back.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you back. What did you think of all those listener suggestions? Pretty good summary, huh?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: That was super. I really have been enjoying hearing people’s memories of that event. There were so many of us. I was 13 at the time. I was glued to the TV, as you can imagine.

But I had, even at age 13, the sense that this was something that was really stopping the world in its tracks to kind of come together for a moment at least and witness something that was absolutely spellbinding, just amazing.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: And I like the fact that people mentioned the view of the Earth, because that to me is one of the great legacies of Apollo. It’s not the reason we went to the moon. And it’s not even something that the people who got to go necessarily anticipated.

But that view looking back at the home planet from a quarter of a million miles away was a leap in awareness for the human race. And I think, even after all this time, it’s something that still can inspire us to recognize that we live on a very precious and beautiful planet, an oasis in space, as Jim Lovell called it on Apollo 8, and to really hammer home the fact that, hey, we’re all really one tribe living on this spaceship Earth. And we should really try to get along and do better at living and working together.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I know the astronauts were always exquisitely planned. Everything was planned. Was that shot, the Earthrise, was that a planned photo?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Well, that’s a personal question, because I was very invested in figuring out who took the picture. Frank Borman, the commander of Apollo 8, had claimed for years that he was the one who took it, and not only had he taken it, but that he’d had to grab the camera away from his rookie crewmate Bill Anders, who apparently was so invested in the photo plan that he didn’t want to take it.

And nothing could be further from the truth. The fact is that Bill Anders was the one who was looking out the window. And by surprise, you’re absolutely right, saw the Earth coming up. He was the one that took the picture.

It was not something that he anticipated. And as he told me when I interviewed him in 1987, even while he was still circling the moon, it began to dawn on him. We came all this way to study the moon. But it’s really the Earth that’s the most fascinating part of this flight.

IRA FLATOW: And Apollo was a great technology accelerator too. One of our listeners in the VoxPop mentioned the computer chips. We wouldn’t be having these little phones and things of if it were not for the space race.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Yeah, absolutely. It’s really amazing to go back and look at the effect of the space program on microelectronics, even the testing of microelectronics, because you had to make sure that these little transistors and resistors and things didn’t fail during the mission.

A tiny little component failing could derail the whole thing. So NASA and its industrial contractors actually advanced the state of the art in the testing of electronic components.

IRA FLATOW: Another comment that I recall very vividly, and a listener mentioned, is how Apollo united us. I think that 1968 was probably the worst year in the world after World War II. We had two assassinations. We had riots. We had all kinds of stuff going on.

And then we took time out both for that famous Christmas of ’68 and then the landing in ’69.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Absolutely. It would be a mistake to think that the entire American public was solidly behind Apollo throughout the 1960s. That was not the case. Public opinion polls show that public opinion was in fact divided.

But I think when it happened– there’s a famous story even about the day before the Apollo 11 launch. The reverend Ralph Abernathy led a group of protesters to the Space Center in Florida. And the NASA administrator Tom Paine came out to meet with them and said, I’m very sympathetic to your concerns about poor people in this country. And if I knew that I could help poor people in this country by saying, let’s not push the button tomorrow, I would do that. But that’s not the way it is.

And Ralph Abernathy in return said a word of thanks and that he was humbled to be there. And he actually got to see the launch. And I think, no matter what your politics was, that was a moment that just really got through the differences.

And the other thing I want to mention, and Mike Collins, the Apollo 11 astronaut has been talking about this. When they went on their world tour after the mission, instead of hearing from people that they encountered in all these different countries, instead of hearing something like, you Americans, you pulled it off. People that they encountered said, we did it. They all felt that they had somehow been part of this great adventure.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. The space race, as we used to call it, was really a political race between the Soviet Union and the US. But of course, there were some legitimate science issues going on there, were there not?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Well, when you say science issues, you mean the–

IRA FLATOW: The experiments and things that were tried and left on the moon.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Oh, absolutely. Science was not the driver for Apollo, the Cold War was. However, the scientists certainly realized that this was an incredible opportunity to study the moon in situ for the very first time.

And not only the experiments that we left behind, the seismometers and so forth on the several different missions– it wasn’t just Apollo 11. It was six different landings. But the photography of the moon from orbit, from the surface, and the samples. The lunar samples are another of the great legacies of Apollo, because they unlocked the door to deciphering the earliest history of the solar system.

IRA FLATOW: And aren’t they waiting to open up another sample that had not been opened?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: They are. There’s a core sample from one of the later missions that is going to be opened I think maybe this year, if I’m not mistaken. But NASA has done a very smart thing. They’ve kept a lot of the samples protected in vaults, stored in nitrogen to prevent any alteration, because they understood that the technology to study those samples was going to improve with time.

So yes, there’ve been pieces of the moon that have gone out to scientists for the past 50 years. But there’s a lot more that is waiting for better technology to be developed.

IRA FLATOW: There’s also been stuff in the news about the moon actually being seismically active. And they left those seismic sensors there, correct?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: They left them there. But now, you may remember this, Ira. They actually turned off the lunar science stations in 1977 to save money, if you can believe that.

IRA FLATOW: Don’t get me started.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: I know, I know. So the data set is limited. But I’ll tell you, one of the coolest things is that recently, in the last few years, scientists have used modern technology to go back and look at things like the seismology data, the data from the rather small network of seismometers. And they’ve actually figured out more details about the interior structure of the moon and the fact that there appear to be features called lobate scarps, which are seismically active.

We actually are seeing clusters of shallow moonquakes in these features, which basically represent two pieces of the lunar crust moving past one another, a little bit like what we think of with plate tectonics on the Earth. But of course, the moon has no plate tectonics. It has no crustal plates. So it’s nothing anywhere near that. But it’s still fascinating to think that, with these modern techniques, we can go back to old data, and we can put out new information.

IRA FLATOW: And for students and teachers out there, we actually put together a collection of the data collected by the Apollo mission seismometers. So you can use real data to decide for yourself if future lunar explorers need to worry about moonquakes. And you can check all that activity out in our Apollo special on our website at sciencefriday.com/apollo.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow talking with Andy Chaikin about the Apollo program and the Cape Canaveral launch pads for Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and the space shuttle. You know that they sit on the east coast of Florida, because it’s near the equator. And when you launch a rocket eastward from there, it gets a little boost from the rotation of the Earth. It’s great for getting into space, getting to the moon. And of course, if a rocket goes awry, it will crash into the ocean and away from populated areas.

But now, almost 60 years later, the ocean is the problem, corrosive sea air rusting at the beach-front rocketry. You have rising sea levels threatening to submerge historic sites and any possible future launch pads.

Our producer Alexa Lim went down to the original Apollo launch sites in Cape Canaveral to have a look around.

ALEXA LIM: Complex 34 was one of the sites where Apollo history was made. The tragic fire of Apollo 1 happened here, where the astronauts burned on the launch pad during a test run. Just one year later, Apollo 7 launched from this site.

SPEAKER 1: We still are a go at this time.

ALEXA LIM: Sending the first crew into space for the mission.

SPEAKER 2: Three, two, we have ignition. Commit liftoff. We have liftoff. This is launch control. We have cleared the tower.

ALEXA LIM: Today, the complex is quiet. And the only sounds I can hear are a few scrub jays calling out and the ocean waves in the distance. And standing in the middle of it, it’s hard to tell where I am. Brazilian pepper trees have taken over the area. And tree trunks poke out of tunnels that used to carry communication cables.

There’s a rusting launch table which once held a Saturn IB rocket. And crumbling buildings with doors pried open dot the perimeter.

LORI COLLINS: I always think of planet apes when I come out here. It’s like, what’s happening here.

ALEXA LIM: I’m with Lori Collins, who is an archaeologist with the University of South Florida in Tampa. She’s trekked through tropical jungles in Central America, uncovering 2000-year-old stone sculptures. And she’s surveyed medieval monasteries in Armenia.

Lori’s now focusing on sites that are a little more modern, the decommissioned NASA launch complexes on Cape Canaveral. They’re the ones used in the early days of spaceflight, during the Gemini and Apollo missions.

On Complex 34, most of the original structures are gone.

LORI COLLINS: These things weren’t necessarily meant to last. They weren’t thinking about that when they were designing these.

ALEXA LIM: Lori’s goal is to salvage what’s left, to build an archive of how the engineers originally built this place, and to create a resource that modern day engineers can use as they prepare for future missions.

LORI COLLINS: I like to say that it’s like an endangered species, that these are treasures that, once they’re gone, they’re gone.

ALEXA LIM: She starts by giving GPS points to the structures that are still here and makes estimates to the missing features. After her team lays out the pieces like a giant jigsaw puzzle, they start scanning.

LORI COLLINS: I did a position map from the last standing.

ALEXA LIM: They use lasers and 3D cameras to record the details of the launch pad down to the millimeter scale. And one of the elements she’s working on looks like two rusted steel skateboard ramps. The Saturn 1B created 1.6 million pounds of thrust at launch. That’s six times more than a 747 airplane. So they needed these steel ramps to deflect the huge flame and prevent it from incinerating everything and everyone nearby.

LORI COLLINS: It would’ve moved one of them in. And it would have come right up underneath the pedestal there to be able to deflect the blast, basically, from the launch vehicle.

ALEXA LIM: Lori’s creating a type of virtual museum of these artifacts.

Just across the Bay is the epicenter of modern spaceflight, Complex 39B. It’s home of the active launch pad for NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Regina Spellman is NASA’s senior project manager for the pad. She’s in charge of construction on 39B, where future spacecraft will roll in and get hooked up for launch.

REGINA SPELLMAN: We’re kind of like the RV park. When the RV shows up, we’re all the connections.

ALEXA LIM: Regina’s prepping the pad for NASA’s next moon mission called the Space Launch System, or SLS. She’s retrofitting the remnants of Apollo. If Lori Collins is like the archivist preserving the layouts of the historic launch pads, then Regina is the architect building on top of those blueprints.

REGINA SPELLMAN: It’s because of the history. It’s like building a brand new house versus remodeling an old Victorian home. Sometimes you don’t know what’s behind the wallpaper.

ALEXA LIM: I follow Regina to the big renovation project she’s working on now.

REGINA SPELLMAN: We’ll go over here, and you guys can see the flame trench.

ALEXA LIM: That’s right, the flame trench. It’s a 50-foot deep fire moat.

How hot is it going to get?

REGINA SPELLMAN: About 4,000 degrees.

ALEXA LIM: The SLS rocket will produce 8.4 million pounds of thrust, five times more than the Saturn 1B. So a wheeled-in flame deflector won’t do the job here. The upgrade involves pulling out the Apollo era bricks and lining the trench with 100,000 new fire-resistant ones.

Every past mission, from Apollo to the Shuttle program, is still here. And you can see it in the pipes, wires, and towers built into the complex.

REGINA SPELLMAN: That’s our new elevator. That’s brand new. Some of these platforms over here, the electrical platform, that was built under the Shuttle program. The one closest to us, the facility connections, that was Apollo.

You can see the three different generations all working seamlessly together. We’ve just continued to build on our historical past.

ALEXA LIM: Back at historic Complex 34, I take a walk along the beach with Lori Collins. There are huge, bleached out shells and what I think are pumice stone and driftwood. But when I take a closer look, I realize they’re chunks of concrete and rusted piping. They’re pieces of Complex 34 breaking apart and slowly making their way out to sea.

LORI COLLINS: See where the fence line is? Kind of right there, that area’s got a lot of features that you’ll see eroding.

ALEXA LIM: The rest of the Space Coast could look like this in the future, because sea levels in this area are predicted to rise 5 to 8 inches in the next three decades. Pair that with the hurricanes that hit and beaches that are washing away, this hub of activity for NASA, SpaceX, and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin sits at a vulnerable spot. And it’s something that Regina Spellman thinks about back on Complex 39B.

One of the projects on the complex is a 3-mile sand dune around the area. Don Dankert heads up that project for NASA.

DON DANKERT: Our number one concern is shoreline erosion. When we have a storm, we want to protect the inland infrastructure from those storm surges and from the potential for inland flooding.

ALEXA LIM: In this modern day space race, the players are different, but they all have to contend with the same existential question. How will the Space Coast battle a future with rising sea levels and climate change? For Science Friday, I’m Alexa Lim.

IRA FLATOW: Also with Alexa, digital producer Daniel Peterschmidt toward the launch sites. And you can see magnificent photos of their trip to these abandoned launch pads. And as a bonus, we have an interactive tour via Google Earth that will take you on a tour of these sights. It’s all up on our website at sciencefriday.com/apollo.

Still with us is Andy Chaikin, space historian and author of A Man on the Moon. Andy, is it sort of nostalgic to go down and see everything that’s just rusting away?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Yeah, yeah. It’s always mixed feelings. It’s a sense of sadness that these things are not going to last forever. They weren’t capable of it. But on the other hand, so inspiring, so amazing.

Go to one of the centers where you can see an actual moon rocket. There’s one in Houston. There’s one in Huntsville, Alabama. There’s one in Florida at the Space Center in Florida. Go stand next to that thing. And remember that it was all done with 1960s engineering.

And that, to me, is the other great legacy here is that human beings, all those years ago, figured out how to do this stuff. And it took 400,000 people working for the better part of a decade. And what I actually do now is I go into NASA and other places like the Missile Defense Agency, and I talk about, how did they do it from a human behavior standpoint.

It was almost like the country funded an experiment in how to do hard things with huge numbers of people. That’s a lesson of Apollo that will live on and is still valuable.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones. Lots of people would like to talk. Let’s go to Reno, Catherine. Hi. Welcome to Science Friday. Catherine, are you there? Catherine? No. Oh, that’s too bad.

She was telling us on the screen here, she visited her brother at the fire station. And the day before, a Basque shepherd had come to the fire station camp. This was during Apollo 11, because the shepherd had a radio of some kind and told the brother that we had landed on the moon, the brother speaking Castilian Spanish.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Amazing.

IRA FLATOW: A lot of people have really– I was watching photos the other day of Times Square. I’d forgotten. I was a teenager. We all were watching together. And here’s another memory. Let’s see if I could get a listener on the phone. Let’s go to Lee in Santa Cruz. Hi, Lee. Welcome to Science Friday.

[ELECTRONIC SOUNDS]

Oh, we’re having more trouble with the phones today.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: We can land a man on the moon, but–

IRA FLATOW: And that’s funny that you say that, because there are a lot of little sayings that came out of the space race.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Right.

IRA FLATOW: We can land a man on the moon, but we can’t get the phones to work. Also, what, the term moonshot?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Yes. Well, again, this boils down to the lessons that Apollo gave us. One of the things that you have to have is a goal that is clear and compelling. And my god, we had that with President Kennedy’s challenge.

But you also have to have sufficient resources to accomplish the goal. And that’s something that we don’t usually see.

IRA FLATOW: Here’s a tweet. Let’s go to the tweets, because they’re working. Alex tweets, “I remember my third grade weekly reader–” I remember weekly reader. “–an education magazine publishing and edition devoted to the future of the space program. It detailed a one, comparatively vast permanent space station on the moon by 1999, and two, a moon base by 2010.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: “We’re way behind that. Can we get back on track if we choose to?” What do you think?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Well, it’s a different reality, of course. Apollo was funded like a war, because it was, in fact, a proxy for a shooting war. It was a way of fighting a battle in the Cold War without actually dropping any bombs or launching any missiles.

Today, the challenge is a bit different. We have to figure out how to do human spaceflight in a way that’s sustainable and doesn’t break the bank. And that’s one of the reasons why I think the work by folks like Elon Musk with his SpaceX rockets and Jeff Bezos with Blue Origin, those things are very exciting, because they are trying to figure out how to do it differently in a way that is sustainable.

And I think that when we can remove the economic barrier to just getting into space and then going beyond Earth orbit, then I think we’re going to start to see a little closer to what we all watched in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 way back in 1968.

IRA FLATOW: I remember a quote. I thought it was by Arthur C Clarke, but I can’t really find it. But I remember it very distinctly. I think it was on the 25th anniversary of Apollo. And he was still alive. And he was asked, I think, what was the most amazing thing about the Apollo the launch system. And he said, the most amazing thing is that we could go to the moon and never go back.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Yeah. That’s exactly right.

IRA FLATOW: Did he say that? The most amazing thing.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: I actually have not heard that. That’s a great quote, which I have not heard before. But I agree with him.

Nobody at the time thought, least of all Arthur C Clarke, but certainly nobody at NASA thought that you and I will be talking about this 50 years later and have it be so long since not only the first landing on the moon but the last landing, which was in 1972.

But I’ll tell you a story just to hammer that home. NASA’s chief spacecraft designer was a brilliant engineer named Max Faget.

IRA FLATOW: Sure.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: And he told me a story. One day in the 1970s, he and his former boss, Bob Gilruth, were walking along the beach at Galveston. And there was a big, bright moon in the sky overhead. And they stood there looking at it.

And Bob Gilruth turned to him and said, Max, someday, people are going to try and go back to the moon. And they’re going to find out how hard it really is.

And I think that means all the stuff that you can’t put down on paper, that you can’t put in a NASA Experience Report about how they solved these daunting problems and how you make a team like that work. We have to go back and revisit Apollo to remember those lessons and take them forward.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I’m talking with Andy Chaikin, author of A Man on the Moon. And that lesson that you say about working together is one of the points made by people who say, if you let the space industry languish, we’re going to lose the talent that knows how to do these sorts of things.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: That’s absolutely right. The amount of corporate knowledge that we have loss is really regrettable. And so we’ve got to kind of pull ourselves up by our bootstraps.

But some of this is not about technical expertise. The technical stuff, as hard as it is, is not the stuff that really could trip you up. Your report on those launch pads mentioned the tragic fire that killed three astronauts in 1967 on the launch pad, the fire that swept through their capsule.

And it’s amazing to think that NASA was not able to perceive the danger. They were putting those three astronauts into with wires that were exposed and vulnerable to damage, flammable materials like Velcro and nylon netting. But most of all, a cabin atmosphere of pure oxygen at 16.7 pounds per square inch. And that danger just somehow, as Mike Collins said to me many years ago, we were blind to them.

And I think we have to recognize the limitations of ourselves as human beings. We’ve got to be what one of my buddies at JPL calls properly paranoid. We’ve got to be a little bit running scared. That recognizes that we’ll never know everything we need to know, and we’ve got to be on guard.

IRA FLATOW: One thing we keep getting asked all the time about, are the flags from the various Apollo missions still standing at them? Can we see them with a telescope?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Well of course, you can’t see them with a telescope, because no telescope, not even Hubble, is that powerful. But we can see the landing sites in amazing detail thanks to NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been circling the moon now for almost 10 years– or actually, excuse me, a little more than 10 years. It arrived in the summer of 2009.

The cameras on LRO are so good that if you look, for example, at the Apollo 11 landing site, you can see Neil Armstrong’s tracks as he ran back from the lunar module late in the moonwalk to take pictures of an 80-foot diameter crater that was about 200 feet behind the LEM.

But even on that image, the flag is just a dot. But we know from Buzz Aldrin’s description as he was looking out the window when they blasted off from the moon that the blast of the ascent rocket knocked the flag over. So at least that one is not still standing. Probably the other ones are. But they’ve been seriously degraded by the intense solar radiation and other forms of radiation.

IRA FLATOW: We know how sun bleaches the colors out of things if you leave them outside.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: And plastics and things like that are just degraded by things like that.

IRA FLATOW: So those flags are, if they’re still up, they’re not those kinds of flags anymore.

We’re going to take a break and come back and take lots more questions for Andy Chaikin, author of A Man on the Moon. He’s a visiting instructor at NASA and teaches human behavior elements of success in spaceflight. We’ll be right back after this break. Stay with us.

You’re listening to Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking with Andy Chaikin. He’s author of A Man on the Moon and taking your questions.

A bit of Apollo trivia for you, Andy. Was Neil Armstrong supposed to be the first person to step off that lander? He’s the captain. Isn’t he supposed to go second? I know there’s an interesting story behind that.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: There is an interesting story behind that. When I was writing my book, I was very interested in that question. And what I found out at that time was that the early versions of the checklist, which had been in the works even before Neil was assigned to that mission, showed that the co-pilot, or in this case the lunar module pilot, would be the first guy out. And the precedent for that was during the two-man Gemini missions, the co-pilot had been the one to do the spacewalks.

Now, Pete Conrad, another Apollo commander, pointed out to me that that was no longer a valid precedent, because once you landed on the moon, you were no longer in flight. And he, being a Navy guy, likened it to when you have a Navy ship that arrives in port, the captain is the first person down the gangplank.

IRA FLATOW: Aha.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Now, mixed in with all of that was the story that everybody had heard again and again which said that, oh, well, the hatch opened the wrong way. And the cabin was so small that it really didn’t make sense to have Buzz get out first. And that was even something that Neil seemed to agree with when I talked to him.

But in more recent years, a new story has come out from James Hansen who wrote Neil’s biography, his official biography. And according to the interviews that he did, some of the leaders of NASA, Bob Gilruth, who we just mentioned, Chris Kraft, who was the head of Mission Control and all the flight controllers, Deke Slayton, the chief astronaut, and George Lowe, who was the spacecraft program manager, got together in the months before Apollo 11.

And they said, look, the guy who is the first on the moon is going to be a historical figure right up there with Charles Lindbergh. And he’s going to have to have the temperament to handle that. And it was their feeling that Neil, by his temperament, was much better suited to that position. And so apparently, that’s how the call got made.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm, that’s interesting. And in the few minutes we have left to speak with you, how about another bit of trivia about Neil Armstrong and that famous line, one small step? There’s controversy that he said, this is not just one small step but a. Word a was in there, right?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Right. So the quote that he had intended to say was, that’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind. And when I interviewed him, he explained to me that in his mind, it was a small step but a significant step, and that’s how he came up with the quote.

I personally don’t hear the a when I listen to the recording. It’s just too small an increment of time. It’s a tiny fraction of a second between the word for and the word man.

In more recent years, someone did some sophisticated analysis of the audio waveform and said, no, no, it’s in there. It’s just that Neil was speaking in the pattern that and Ohio boy would do “for a man.”

I’m sorry. I still don’t hear it.

IRA FLATOW: Did he write it himself, do you think?

ANDREW CHAIKIN: He did.

IRA FLATOW: He did.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: And apparently, he had sort of zeroed in on that and maybe one other possibility before the flight but didn’t make the final decision until they were on the moon. I think in the heat of the moment, it just came out without the word a. But it’s a great quote anyway.

IRA FLATOW: It’s a a greet quote.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Wonderful thing.

IRA FLATOW: And it’s great to have you on to remember all of this with us, Andy.

ANDREW CHAIKIN: Thank you Ira. It’s always good to be with you.

IRA FLATOW: Great to have you back. Andy Chaikin, space historian, author of A Man on the Moon, terrific book. He’s also a visiting instructor at NASA, teaching the human behavior elements of success in spaceflight.

And you can check out all our Apollo coverage, including a behind the scenes tour of the Apollo launch pads all up there at sciencefriday.com/apollo.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.