Keeping The Nuclear Bomb Out Of Hitler’s Hands

During World War II, two French physicist’s assistants escape German occupation with a crucial nuclear weapon ingredient before the Nazis get to it first.

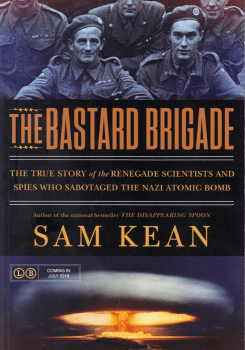

The following is excerpted from The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb by Sam Kean.

The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb

Editor’s note: Heavy water (D2O) is a form of water in which the hydrogen molecules are largely or entirely replaced by the isotope deuterium. It can be used to make nuclear weapons.

Several members of the German atomic bomb project considered heavy water every bit as vital to their ambitions as uranium. The French heavy water heist in March 1940 therefore left them fuming. But the invasion of Norway the very next month quickly bucked the Germans up. Oslo fell immediately, and although the feisty men and women of central Norway continued to fight for weeks, when the resistance there collapsed in May, the Third Reich seized the Vemork power plant. Adolf Hitler now commanded the only heavy water production facility in the world.

Meanwhile, German Panzers were steamrolling France as well, roaring past the Maginot Line and crushing every pocket of resistance they encountered. Although still at some remove from the front, the people of Paris panicked. Thousands fled, and once sober government officials began tossing whole cabinets of documents out their windows to the lawns below, to burn in gigantic bonfires. Anarchy reigned.

Although calmer than most, Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie received orders in mid-May to evacuate the heavy water in their possession. (Editor’s note: Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie were a physics Nobel Prize-winning couple who became members of the resistance.) Under no circumstances could the Nazis get their talons on it. So one night at 10 p.m., two of Joliot’s assistants grabbed a pistol, loaded the canisters into a Peugeot truck, and began rumbling south.

Jacques Allier, the banker-spy who’d pulled the airport heist, had made some calls and arranged for the assistants to deposit the canisters in a bank vault 250 miles away. Refusing to say what the material was, the assistants registered the heavy water as “Product Z.” It stayed there five days before the bank manager got itchy and demanded its removal. The assistants located a temporary home in a nearby women’s prison, then transferred it again to a maximum-security jail. Some of the inmates helped haul the canisters inside, placing them in a reinforced cell on death row normally reserved for violent offenders.

Joliot and Irène lingered in Paris as long as they could. (And meanwhile evacuated their children, Pierre and Hélène, to the family cottage in the fishing village of L’Arcouest, where young Irène had spent the beginning of World War I.) With the Germans just 50 miles away, the Joliot-Curies finally retreated on June 12. As they drove south, the smoke from burning oil refineries filled the sky. They carried with them some equipment from their lab, as well as Irène’s birthright—the 130-pound lead-lined case containing the gram of radium that the women of America had given Marie Curie.

Early on the 16th, the Joliot-Curies reached the prison town, where they hoped to set up a new lab with the heavy water. But while Joliot was taking a stroll that afternoon, scoping out the town, a car pulled up and Allier jumped out. The French army had crumbled even more quickly than expected, and they had to evacuate again. Allier ordered Joliot to send the heavy water to Bordeaux, in western France, and from there ship it to England for safekeeping. Although reluctant, Joliot agreed. Allier then went to the jail to retrieve the canisters—not without difficulty, since the jailor refused to relinquish them at first. He came around to Allier’s point of view when the banker shoved a pistol into his ribs. The doughty prisoners once again helped out by loading Product Z onto a truck.

Two other Joliot assistants escorted the D2O this time, leaving the prison at dawn on May 17 and winding their way through the hilly countryside between central France and Bordeaux. Exhausted, they arrived at 11 p.m. and checked with military officials about an evacuation ship. They were assigned to the Broompark, a Scottish coal steamer under the command of Charles Henry George Howard, the 20th Earl of Suffolk.

The next morning, the assistants wandered down to the dockyard to find the Broompark. What they found instead was bedlam. Half a million refugees had swamped Bordeaux, every last one of them desperate to flee. To make matters worse, the diabolical Germans had mined the harbor, and every so often a squadron of planes swept through to strafe. The day before, an aerial bomb had bull’s-eyed an ocean liner and killed 3,000 passengers.

The situation seemed even more hopeless when the assistants found the Broompark and met the captain. Although a peer of the realm—his family line predated the House of Windsor—the Earl of Suffolk was known to most people as Mad Jack. That day the assistants found him stripped naked to the waist on deck, whacking his thigh with a riding crop and showing off his myriad tattoos (a bizarre affectation then). He had a woman hanging on each arm, one blond and one brunette, and was cracking dirty jokes in an excruciating French accent. With his noticeable limp and full beard, he looked like an “unkempt pirate,” one witness recalled. Swallowing their misgivings, the assistants asked him if the Broompark planned to sail soon—they needed time to load the canisters. Never fear, said Mad Jack. The Broompark should have sailed already, but he’d taken the crew out the night before and gotten them stinking drunk, buying round after round until they’d collapsed. They were currently nursing the worst hangovers of their lives, and it would be at least a day before their stomachs were shipshape. So there’s plenty of time to load everything, he assured them. This was what passed for a plan in Mad Jack’s world.

That same day, May 18, the new prime minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, gave one of his most famous speeches, the “finest hour” talk. (“Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”)

Few people remember that he also warned against “a new dark age made more sinister… by the lights of perverted science.” Those unlucky few who understood the threat of atomic weapons must have swallowed hard.

The Broompark finally sailed at 6 a.m. on June 19 with 101 souls aboard, each one clutching the inner tube of a car tire as a life preserver. In addition to the heavy water canisters, Mad Jack had taken on two crates of diamonds from Amsterdam and Antwerp worth $15 million ($250 million today); they represented the bulk of the European diamond market. To protect this precious cargo, the earl had also scared up two 75mm guns and three machine guns. He hadn’t found any ammo yet, but he wasn’t worried. Bordeaux sat at the mouth of an inlet, 70 miles from open ocean, and he planned on stopping at a city along the coast for bullets and shells.

When they arrived at the coast, around noon, the tide was changing, and while Mad Jack limped off to ask about ammo, disaster nearly struck: A ship anchored next to the Broompark drifted into a mine and blew sky high. The scientists were actively trembling by this point, but when Mad Jack returned, he slapped them on the back and told them not to worry: He figured they had at least a fifty-fifty shot of reaching England alive. In fact, the explosion gave him an idea for a project. They would build an “ark” out of wood scraps to save the heavy water and diamonds in case the worst should happen. Work would take their minds off bombs and torpedoes anyway.

“You know, the story of two scientists fleeing for their lives from an implacable enemy and carrying the world’s supply of rare material which will enable them to master a new force of nature? It was preposterous, it was dime-novel stuff.”

Leading by example, Mad Jack stripped to the waist again and lit up two cigarettes, which he smoked simultaneously using a special filter. He then grabbed a hammer and began pounding nails for the ark. Others joined in. A born raconteur, perhaps he took advantage of the crowd to regale everyone with the story of his life. Craving more adventure than the family estate near Oxford could offer, he’d sailed for Australia in a merchant ship while still a teenager, and had begun acquiring tattoos on far-flung isles as souvenirs. After a few years bouncing back and forth between Australia and England (a period that included his dismissal from the Royal Navy for insubordination), he’d decided to study chemistry and pharmacology in Edinburgh. Lest anyone should think he’d become conventional, he married a notorious nightclub dancer from Chicago. A few years later, in June 1935, he fell ill with rheumatoid arthritis, which hobbled his legs and left him with a limp. When World War II broke out, the army wouldn’t take him, so he volunteered to work as a scientific spy in Paris. He quickly proved the most flamboyant secret agent in Europe, throwing champagne-soaked parties at the Ritz and showing off the twin .45 automatics he kept in shoulder holsters beneath his tuxedo jacket. He’d named them Oscar and Genevieve. (One of Joliot’s assistants recalled thinking, “All this was completely in keeping with the ideas of British aristocracy I had gathered from the works of P. G. Wodehouse.”)

But when his country needed him, Mad Jack proved himself worthy. The Broompark finally reached open ocean on the night of June 19. By that point most of the passengers—many of whom had to sleep on piles of coal belowdeck—were covered in black soot. They looked like chimneysweeps, albeit ones wearing suits and dresses. Even worse, several ships near the Broompark were bombed by German planes on the trip north. Yet despite the terror and discomfort, many passengers had the time of their lives. By sheer force of personality, Mad Jack made the whole voyage seem, as one passenger had it, like a “schoolboy adventure,” limping up and down the deck, cracking jokes, handing out mugs of champagne, which he insisted was the best cure for seasickness. Joliot’s assistant later remembered their situation in almost comic terms: “You know, the story of two scientists fleeing for their lives from an implacable enemy and carrying the world’s supply of rare material which will enable them to master a new force of nature? It was preposterous, it was dime-novel stuff.” And as in any novel worth its dime, the heroes survived their harrowing journey, landing unharmed in England on June 21.

The canisters of heavy water soon ended up in another jail, one with the Dickensian name of Wormwood Scrubs prison. After a few weeks in solitary there, they got a magnificent upgrade when the mad earl personally delivered them to Windsor Castle for safekeeping. Over the next few years these well-traveled cans of water would play a key role in experiments for the Allied atomic bomb project.

Sadly, Mad Jack blew himself up later in the war while engaged in a hobby of his—defusing unexploded German bombs that landed in England, an activity he liked to do while smoking. And despite his heroics on the Broompark, he did fail in one important aspect of his mission. In addition to the heavy water, he was supposed to seize another vital scientific asset in France. But Frédéric Joliot had eluded his grasp.

Joliot had arrived in Bordeaux a few days after his assistants. No matter how much the mad earl begged, though—at one point he seized Joliot’s arm and tried to drag him up the gangplank—Joliot refused to board the Broompark and sail for England. He had several reasons for this. He didn’t speak much English, and he knew he’d probably have to work under James Chadwick there, the man who’d beaten the Joliot-Curies to the discovery of the neutron. Even more important, Joliot was worried about his wife.

Irène had always been sickly, suffering from whooping cough and other ailments as a girl; her parents also had a bad habit of leaving lab coats covered in radioactive dust lying about, which further weakened her immune system. She’d grown even sicker after the birth of her daughter, developing both tuberculosis and anemia. (In an echo of her wedding day, Irène had worked all morning on her due date, taking only the afternoon off to give birth.) Ultimately the stress of the war broke her, and rather than accompany Joliot to Bordeaux, she’d checked herself into a sanatorium in western France to recover.

Even if he’d adored England, Joliot couldn’t leave his sick wife behind—especially not after he’d already abandoned her once to open his cyclotron lab. Moreover, he found her contempt for the Nazis inspiring. “She was convinced,” said her biographer, “that they would not dare lay a finger on a Curie,” no matter how bad things got. Joliot needed such strength, and was determined to stick by her.

Moreover, Joliot still felt a sense of duty to France. Echoing Werner Heisenberg, he told Mad Jack that France needed him and that he wanted to salvage what he could of French science during the German occupation. In fact, he planned to return to Paris as soon as he could. Little did he suspect that the head of the Uranium Club would be waiting there for him.

Excerpted from The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb. Copyright © 2019. Available from Little, Brown and Company, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Sam Kean is a science writer. He’s the author of The Bastard Brigade and Caesar’s Last Breath. He’s based in Washington, D.C.