Revisiting The Debunked Theory Of Spontaneous Generation

16:54 minutes

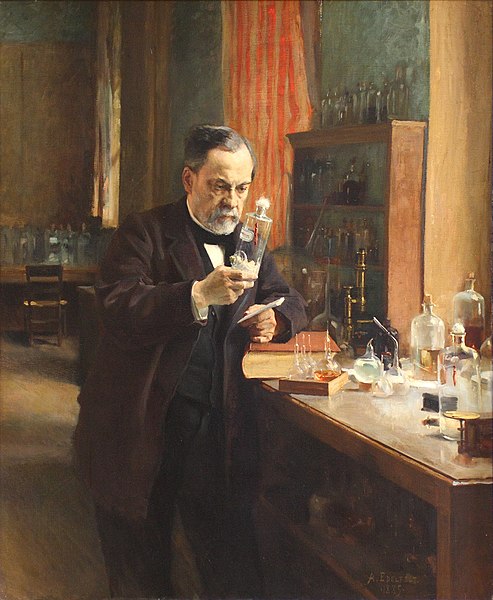

“Spontaneous generation” was the idea that living organisms can spring into existence from non-living matter. In the late 19th century, in a showdown between chemist Louis Pasteur and biologist Felix Pouchet put on by the French Academy of Sciences, Pasteur famously came up with an experiment that debunked the theory. He showed that when you boil an infusion to kill everything inside and don’t let any particles get into it, life will not spontaneously emerge inside. His experiments have been considered a win for science—but they weren’t without controversy.

In this interview, Undiscovered’s Elah Feder, Ira Flatow, and historian James Strick talk about what scientists of Pasteur’s day really thought of his experiment, the role the Catholic church played in shutting down “spontaneous generation,” and why even Darwin did his best to dodge the topic.

James Strick is a professor of Science, Technology and Society at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. And for the rest of the hour, we’re diving into the vaults of science history, because the hosts of our podcast Undiscovered are working on a new series. It’s all, on one of my favorite subjects, all about science history. And co-host Elah Feder is here to tell us about it. Hey, Elah.

ELAH FEDER: Hey, Ira. Yeah, me and my co-host Annie Minoff are really big science history buffs, like yourself. And recently, we got thinking about all of the scientific ideas that we used to think were true, that we’d had accepted as good, solid science until, one day, we didn’t believe them anymore. We’re thinking about old miracle cures or outdated beliefs about the universe, ideas that are often punchlines today. But we wanted to give them a closer look. Why did we believe in these ideas in the first place? What had us convinced? And then what did it take to change our minds? That’s what this upcoming series is all about.

IRA FLATOW: And today, we’re talking about spontaneous generation. It’s really fascinating.

ELAH FEDER: Yeah, so one of the basic ideas in biology is that every living thing comes from another living thing. A horse comes from horse parents. An oak tree comes from an oak tree’s acorn. An amoeba comes from another amoeba that has split in two. And if we work our way all the way back through evolution, all living things come from an original living thing. But for a long time, people believed that some living things didn’t have parents. They just spontaneously sprang into life. We called it spontaneous generation. You might have learned about this in high school.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

ELAH FEDER: So if you kept reading, you would have learned about how a scientist named Louis Pasteur disproved this idea. Science for the win. But it turns out that history is never that simple. Instead of a win for science, this might have been a win for religion. My guest is here to fill us in on the story behind the story. James Strick is a professor of science technology and society at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Welcome to the show, Jim.

JAMES STRICK: Thanks, it’s nice to be here.

ELAH FEDER: So you were a high school teacher for a while. So you know the textbook version of spontaneous generation pretty well. Can you give us the short version of it?

JAMES STRICK: Well, spontaneous generation really has been used most of the time to mean living things coming into being from non-living starting materials.

ELAH FEDER: But the upshot was that life was spontaneously coming into existence. It didn’t necessarily have living parents that brought it into being.

JAMES STRICK: That’s right.

ELAH FEDER: So today, we think of this as an idea that’s been thoroughly debunked. It’s very, very wrong, obviously wrong. But for over 2,000 years, a lot of very smart people believed in spontaneous generation, going all the way back to Aristotle.

JAMES STRICK: Yeah, Aristotle certainly the best biologist of his day in ancient Greece and a real astute observer of nature. When he saw things like eels, and frogs, and tiny fish emerging from muddy river banks in the spring, it seemed pretty clear to him that you had a case of living things coming into being without parents and that it was the influence of the strengthening sun, an element from the sun that he called “pneuma” that interacted with the mud of the river bank to make it capable of producing new life when otherwise it wouldn’t be.

IRA FLATOW: So he was only talking about small living creatures, not elephants and things like that?

JAMES STRICK: Nothing larger than frogs or eels, but to many people that already seems stunning enough in today’s context.

ELAH FEDER: So you see these creatures coming up out of nowhere, it seems like they are just spontaneously emerging. But the Catholic church was very against this idea. Why were they so against it?

JAMES STRICK: For most of the history of the Catholic church, it was not opposed to spontaneous generation. Saint Augustine, for example, in the early fifth century, one of the most important and influential church fathers who left a lot of writings, had no problem at all reconciling spontaneous generation with Catholic doctrine. He thought that God had put seed principles into certain kinds of matter at the beginning of creation and that meant that, over time, they would unfold and develop into living things. But it’s only in the late 17th century when there really comes to be a sharp conflict between the dominant Catholic doctrine and the doctrine of spontaneous generation.

Church is moving away from Aristotelian physics because of all the new discoveries of the scientific revolution. But there’s also new doctrines of preformation and pre-existence to explain where living things come from. They work with Genesis in a way, but not in a way that is compatible with spontaneous generation.

It conflicts with this doctrine that all generations of organisms were created at the beginning, serially in case, that Russian dolls within the eggs or the sperm of the very first member of that species. But also, as you get into the early 18th century, spontaneous generation is seen to potentially be an underpinning for philosophical materialism, the idea that matter alone contains everything necessary to generate life, mind, and that things like the soul and the afterlife are an illusion.

ELAH FEDER: So it kind of seems to cut God out of the equation. You can have life coming up from non-life. I could see why they would object to that. So in the 1800s, you get a showdown between two scientists. You have Louis Pasteur and, somewhat less famous today, Felix Pouchet, over this idea of spontaneous generation. What happened?

JAMES STRICK: Pouchet, in the same year that Darwin’s Origin of Species came out, 1859, Pouchet published a book-length report of many, many experiments that he had done that seemed to validate the possibility of spontaneous generation, at least for microorganisms, even if not for anything larger or more complex than that.

The French Academy of Sciences, the most prestigious body of scientific opinion in France at the time, responded to this by posing a competition. There was a prize of 500 francs for the winner. They said, we challenge every scientist in France to present experiments that can clarify the subject of spontaneous generation.

And, essentially, Pouchet’s book, he entered as his entrance into this competition, and the French Academy, I guess, was waiting to see whether somebody would come in on the other side of the story and claim to have experiments that disproved spontaneous generation, that torch was taken up by a young, at the time, relatively little-known chemist named Louis Pasteur.

ELAH FEDER: So Pouchet had claimed to demonstrate that spontaneous generation was real. What was Pasteur’s problem with Pouchet’s demonstration?

JAMES STRICK: Pouchet’s pushes main line of evidence was what are called “infusion experiments,” meaning you infuse or soak something in water, you boil it extensively to try to make sure that nothing that might have been previously alive could possibly still be alive in there. You boil it in a sealed container for an extended period of time. And then you let the infusion cool down in the sealed container.

And if, over time, the results in there become turbid, cloudy, then you judge that there’s a growth of microorganisms occurring. And in Pouchet’s case, you claim that that proves those microorganisms must have been produced by spontaneous generation. Pasteur did not think that Pouchet’s experiments were sufficiently precise, as he put it. He thought that Pouchet had not adequately sealed his containers to prevent the ability of microbes getting in from the outside.

And Pasteur believed that microbes are widely distributed through nature, riding around, for one thing, on dust particles everywhere. So Pasteur thought that if he could somehow duplicate Pouchet’s infusion experiments but find a way to make sure that dust was kept out, that he could show that in those infusions, you’d never see the result turned turbid. There’d never be the growth of microorganisms in there.

And he came up with a really bright idea. He created what were later called “swan-necked flasks.” He heated up the neck of the glass, flask that the infusion was in in a Bunsen burner flame while the infusion was boiling and drew the neck out into a long, curved shape, where it had a dip in the curve before finally opening with a small opening to the outside air.

And in those flasks, when Pasteur boiled them, never in any of his publicly reported experiments did he ever see any growth of microorganisms. So the French Academy of Sciences pronounced Pasteur’s experiments decisive and judged that Pasteur was right, that Pouchet had not prevented the admitting of dust particles carrying microorganisms because he hadn’t adequately sealed his flasks. And, therefore, Pasteur’s experiments proved that spontaneous generation was impossible.

IRA FLATOW: So it was a slam dunk, then?

JAMES STRICK: That is how it is described in most textbooks, and that is how it was described by the French Academy of Sciences at the time. The interesting thing is that scientists, at the time, split maybe close to 50/50 on whether they found this persuasive or not. An awful lot of scientists, not just Pouchet and his allies, but, for example, Richard Owen in Britain, one of the premier comparative anatomists of the day and, in some ways, an opponent of Darwin in many parts of the evolution debate. Owen said pointedly that, it’s really interesting.

Pasteur doesn’t seem to have proven anything other than that dust is a necessary ingredient for spontaneous generation, just as Pouchet claimed. And the French Academy is premature in declaring Pasteur’s experiments decisive. And Owen was not the only scientist in other countries who had that point of view.

ELAH FEDER: If it wasn’t a slam dunk and a lot of scientists objected, why did the Academy of Sciences declare this a case closed?

JAMES STRICK: This is a time of a politically very conservative government in France that came to power in 1850. And Louis Napoleon, the nephew of the famous Napoleon, declared himself emperor and was supported by most of the Conservative political forces in France, including the Catholic church. So the Pasteur-Pouchet controversy is taking place at a time of politically a very conservative government in France. The French Academy of Science is a government-appointed body and, therefore, under considerable government influence in terms of its point of view, had appointed a jury to judge the Pasteur-Pouchet competition.

And a couple of the people on the jury had publicly before stated that spontaneous generation is absolutely impossible and would be an outrage against all morality and Christian society if it were proven to be true. And yet, they were considered to be able to be objective judges on this commission. And they wanted to declare this case closed and settled, even when many scientists considered the experimental evidence, as we say, underdetermined.

ELAH FEDER: And it sounds like, at the time, a lot of people were capitulating to the church. You mentioned Darwin when we spoke.

JAMES STRICK: You know, his book had just come out two years earlier in 1859. And if you read Darwin’s book and are half awake, you have to realize by the time you get near the end of the book, you know what this guy is saying is the further back in time you go, the fewer and fewer common ancestors there are. And if you go back far enough, all living things must be descended from someone single, common ancestor or, at most, a tiny handful of original ones.

And so the book is kind of begging the question, where did that one come from? Many people perceive Darwin’s book to be a project about getting the supernatural out of the life sciences. This question is so loaded, and Darwin avoids it for almost the entire length of the book.

And then on page 484, almost to the very end, there’s one throwaway sentence on this subject. And what Darwin says, and I’m quoting is, “Therefore I should infer that probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form into which life was first breathed.”

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And that’s where scientists are now, right? Talking about that mystery chemical soup, that primordial soup on earth that could have led to life?

JAMES STRICK: That’s where modern origin of life research is right now. But imagine what an 1859 audience thought when it read that last expression. “Some one primordial form into which life was first breathed.” I mean, it’s clearly biblical language, and it was clearly not selected unintentionally by Darwin.

He’s trying to dodge the question. He knows he’s going to have quite enough difficulty already convincing a Christian audience to accept species change over time. He really doesn’t want to tie his doctrine inseparably, this is my argument in my first book, to the argument that you have to believe if Darwin is right, there is no creator god.

IRA FLATOW: I guess, in a sense, this is, as science history being just a subset of all history, usually, the historians who are the victors write the history.

JAMES STRICK: They sure do. And Pasteur was conclusively declared the victor in France. And a number of people in other countries took up the French Academy of Science’s pronouncement. Textbook writers don’t always follow the primary source literature that closely. They just listened to what the authoritative bodies of opinion say are the outcome of these debates. And so, for generations of biology textbooks written since the 1860s, it has been copied practically word for word from the French academies pronouncement that these experiments of Pasteur prove once and for all that life can never possibly come into being from non-life.

If you’re a modern origin of life researcher, obviously, that’s not right. You obviously believe that, under some circumstances and under the conditions that existed on the primitive earth, it must have been possible. Origin of life research in the 1870s, early 1880s, kind of went in the tank for an extended period of time as a result of the French Academy of Science’s pronouncements about the Pasteur-Pouchet debate.

IRA FLATOW: That’s about all time we have. I want to thank James Strick, professor of science technology and society at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania for joining us. And also, Ellah Feder, co-host of our Undiscovered podcast, who’s hard at work on a new series all about the failed ideas of science history, right? Thanks, Ellah.

ELAH FEDER: Thanks for having us.

IRA FLATOW: And we’ll be hitting the road again in August, this August coming to San Antonio. Yeah, join us Saturday, August 10 for Science Friday Live from the Lone Star State. We’re going to talk about science stories in the San Antonio area. And believe me, there are lots of them. Plus, can’t go to San Antonio without having live music, more, all kinds of fun. That’s Saturday, August 10th, not Friday night, Saturday night, August 10, info and tickets at sciencefriday.com/sanantonio.

And if you’re saying, hey, what about an event near me, you can visit the Events page. Want to know where we’re going to be near you? It’s on our Events page on our website. Sign up for our events there at the same time.

We have a special announcement. We have a new app you can use to add your voice to our shows. It’s a way for us to interact with you, to get you involved in our coverage. It’s available for iPhone and Android, so search for “sci-fri vox pop–” sci-fri vox pop. Wherever you get your apps, sci-fi vox pop, V-O-X P-O-P, and share your voice comments for our upcoming shows.

And we’re active all week on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, all social media. Of course, if you have a smart speaker, ask it to play Science Friday whenever you want to, sitting around, listening, lounging around– play it. And you can email us, yes– scifi@sciencefriday.com. Have a great weekend. I’m Ira Flatow in New York.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Elah Feder is the former senior producer for podcasts at Science Friday. She produced the Science Diction podcast, and co-hosted and produced the Undiscovered podcast.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.