They say that beauty is in the eye of the beholder—but for squid, it’s in the lens.

“A squid lens is infinitely more elegant than our eye,” says Alison Sweeney, associate professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. “The resolution of their eyes is approaching that of humans, their retinas are much more sensitive than ours are to light, and if you dig into the nitty-gritty of how nature figured it out, I’m forever blown away at the level of nuance to get it to work.”

Sweeney studies the evolution of novel materials in nature like wood, muscles, bones, and more. She looks at these things as materials, much like an engineer, and tries to figure out how they came to be. She’s looking at squid eyes due to their large numbers, or as she put it, “if you were a Martian who swooped down and scooped up exactly one animal off of Earth, you are more likely than not to get something transparent and bioluminescent that came from 400 meters in the ocean, because that’s where 99% of the space is.”

Mid-ocean squid live in a world very different than our own. Unlike visually stimulating forests, cities, or reefs that other creatures live in, the world 400 meters below the surface of the ocean is gloomy and featureless. There’s nothing around for miles, and it’s about as bright at noon as a night with a full moon. But “if you’re a squid that’s been evolving for 400 million years to live at that depth,” says Sweeney, “you can see great.”

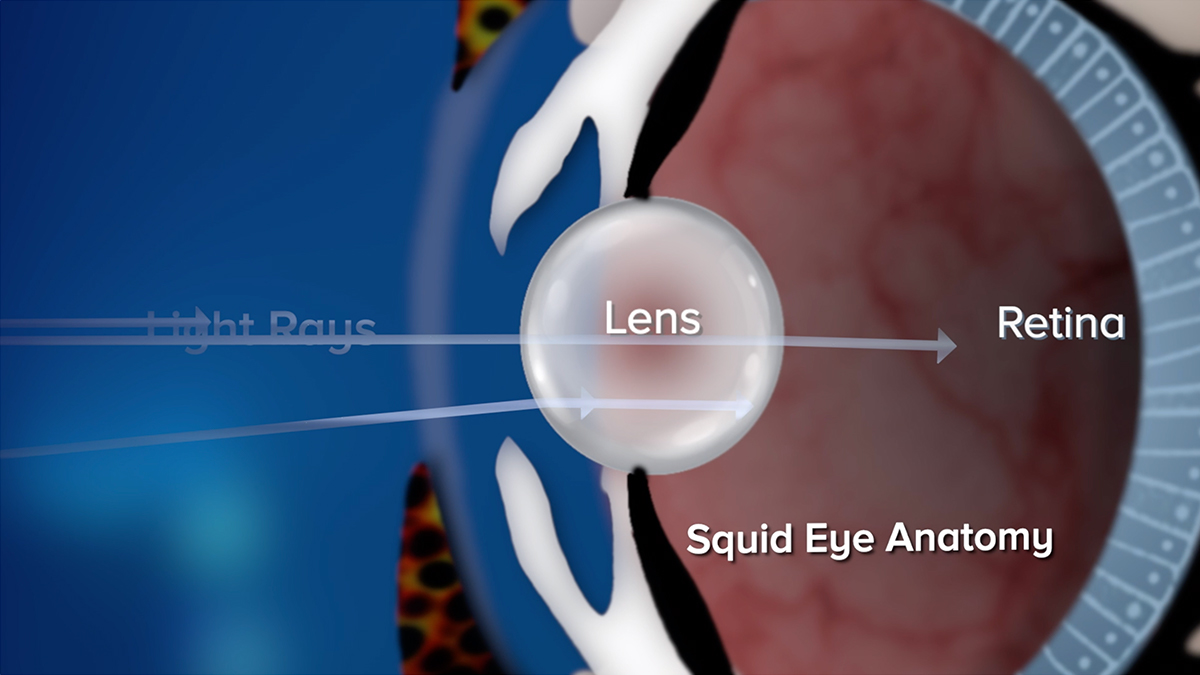

That’s because squid eyes have specially-designed lenses in their eyes that are tailor-made for their environment. For many creatures, including land-loving humans, your retinas determine how sensitive your eyes are to light—the rounder and bendier the retina, the quicker your eye can absorb light. But that comes at a trade-off: “You don’t get a very crisp image out of a spherical lens,” Sweeney says.

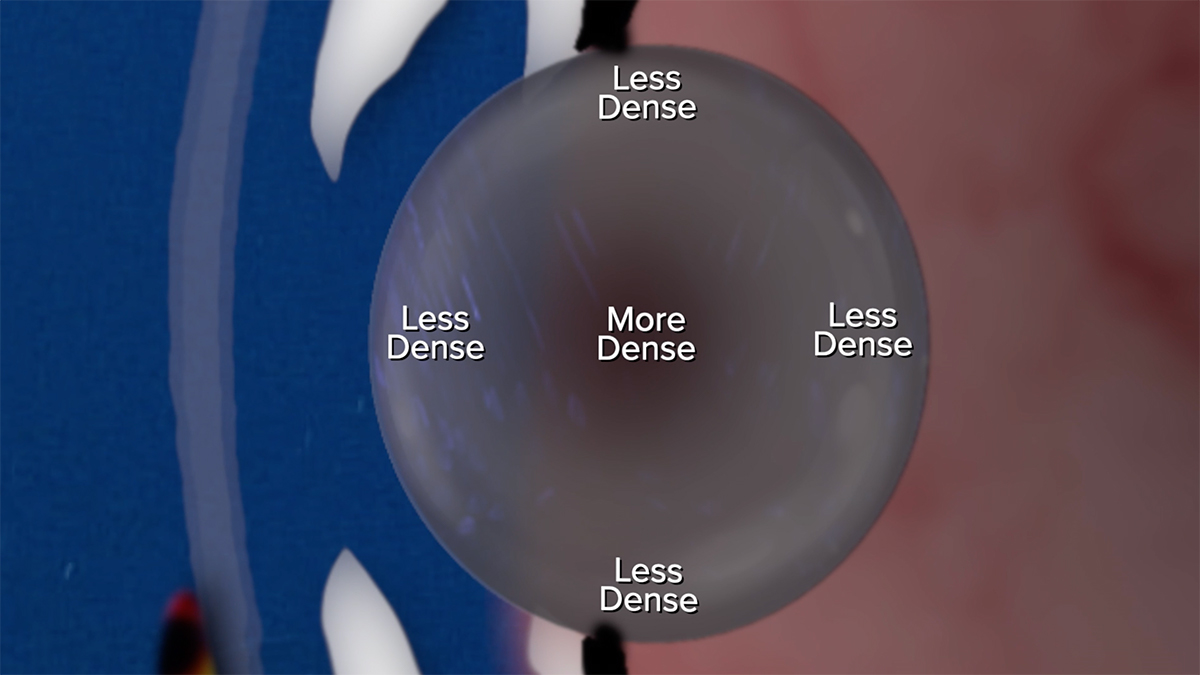

Squid lenses are filled with S-crystallin protein, which were thought to just float in solution. But squid have a trick up their sleeve. In order to get around the sphere-shaped lens problem, squid have evolved to put denser proteins at the center of the lens and less dense proteins at the edges, producing a crisp image every time.

“It’s really sort of a neat trick to find a way to put proteins together in a whole bunch of different densities, such that none of them are going to require any energy to maintain that structure,” says Sweeney.

To see the structure of the squid’s special S-crystallin proteins, the team shot an X-ray through the lens—and they discovered something fascinating.

“What we saw was: A squid lens genuinely self-assembles into this really cool, higher order complex optical structure,” says Sweeney. Imagine you want to build a LEGO castle, she says, and that you “had a bunch of little bricks, put it into a bag, and shake the bag, the castle will just come out again. That’s essentially what the squid lens proteins do.”

Sweeney hopes that researching squid eyes can be beneficial to humans, too.

“We can leverage 400 million years of iterative learning to show us how to make shortcuts at the engineering bench,” she says.

And that is nothing to blow water at.

Credits

Produced by Luke Groskin

Music by Audio Network.com

Additional Footage and Stills Provided by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration & Research, MBARI, Shutterstock and Alison Sweeney

Join Science Friday’s Sea Of Support

With every donation of $8 (for every day of Cephalopod Week), you can sponsor a different illustrated cephalopod. The cephalopod badge along with your first name and city will be a part of our Sea of Supporters!

Meet the Producers and Host

About Luke Groskin

@lgroskinLuke Groskin is Science Friday’s video producer. He’s on a mission to make you love spiders and other odd creatures.

About Brandon Echter

@bechterBrandon Echter was Science Friday’s digital managing editor. He loves space, sloths, and cephalopods, and his aesthetic is “cultivated schlub.”