Grade Level

3 - 5

minutes

1- 2 hrs

subject

Physical Science

Activity Type:

classroom strategy, STEAM, science journals, science comics

Children can develop their own science story using a comic journal approach to record their investigations and findings. This will encourage children to ask deep and challenging questions of their science learning and to explore answers. This is a multi-day series of activities which can be used to build science illustration and reading skills around any topic. Oakham Primary School in Sandwell, West Midlands, England piloted this approach with multiple topic units–space, climate change, and ocean plastics–while learning about science illustration by analyzing the comics of children’s book author and illustrator Karen Romano Young (whose works are featured below).

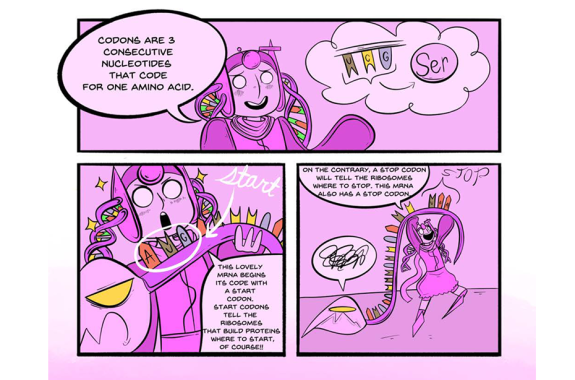

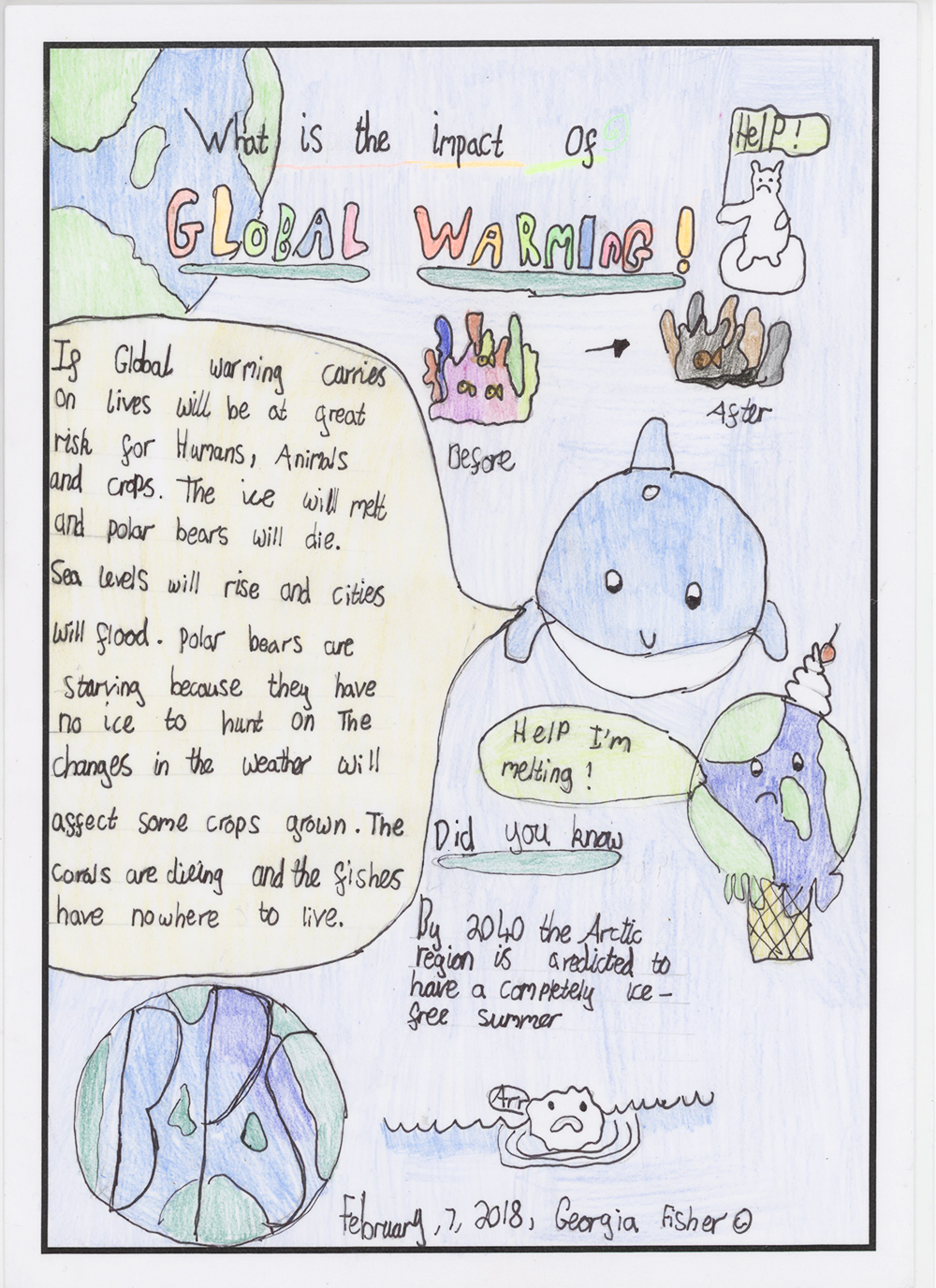

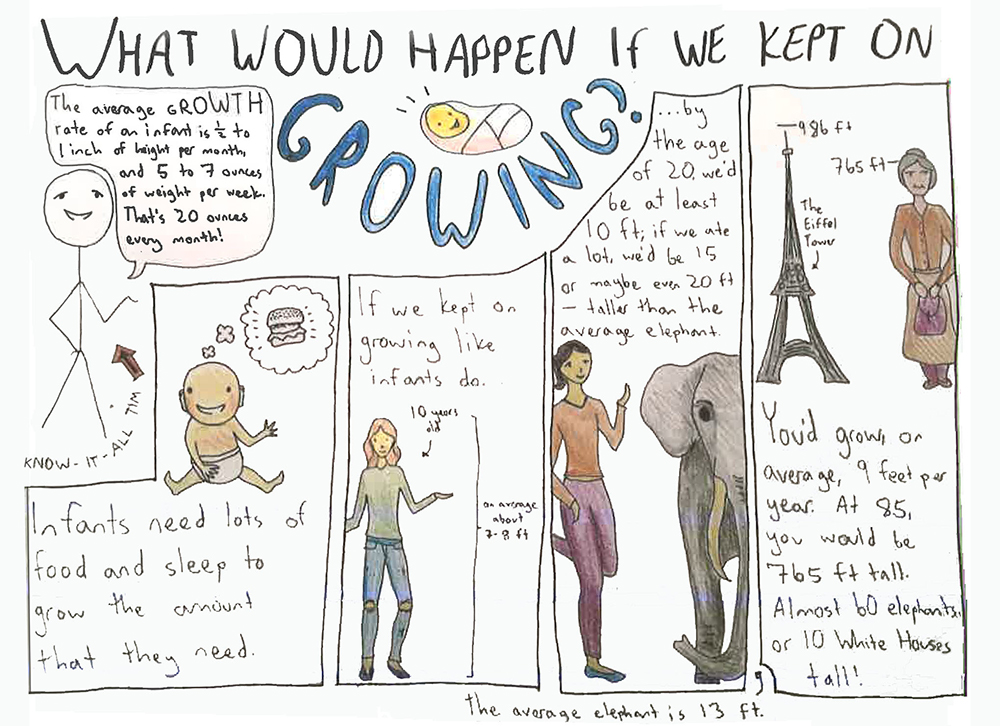

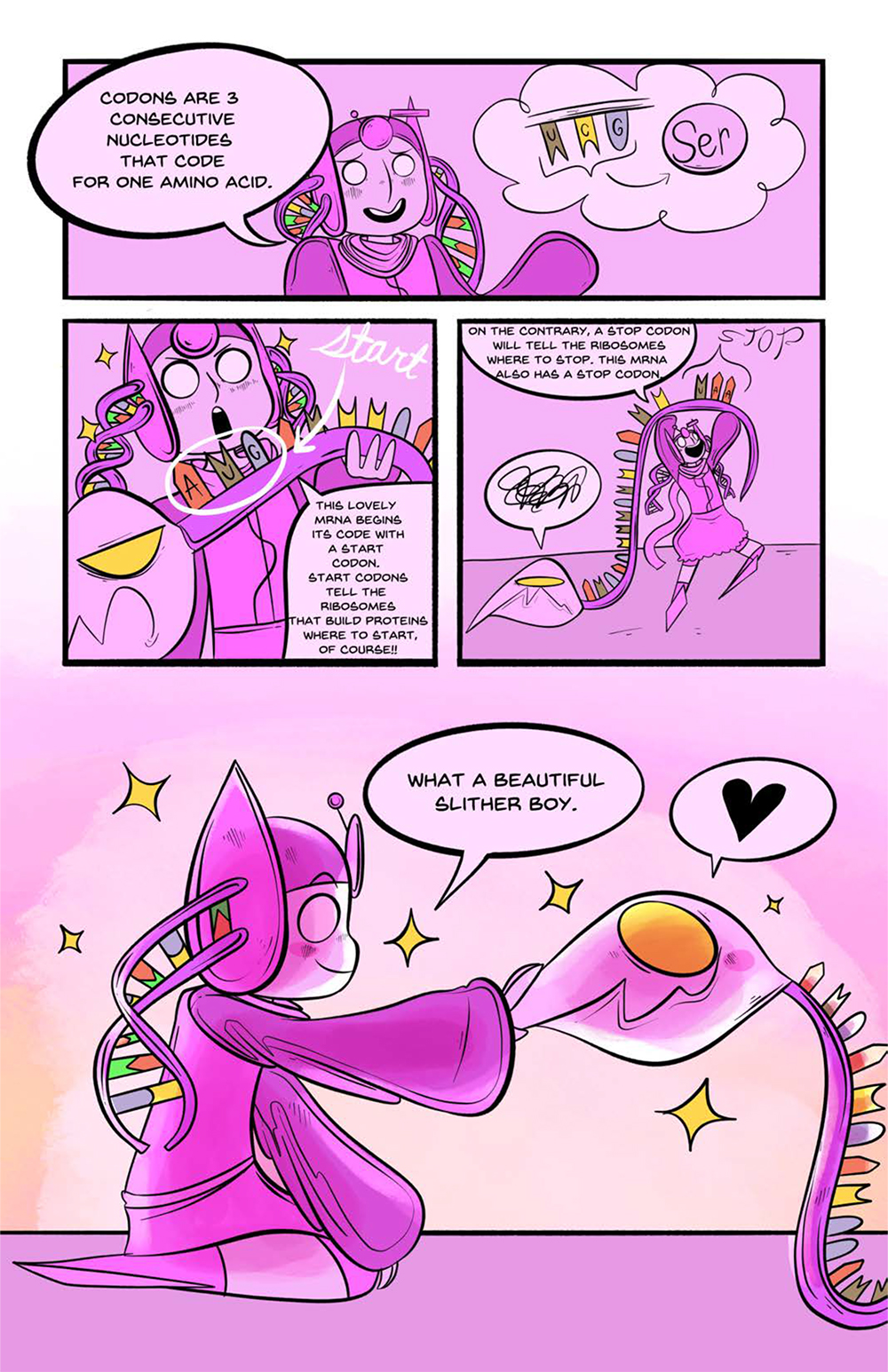

Science comics are packed with the personality and creativity of the students that create them, but also can be powerful tools for organizing new information and useful assessment indicators for teachers–check out these 2019 Science Communication Comic contest winners!

With this brief three-step approach, any STEM classroom can implement comics as a tool for learning the building blocks of effective science communication. First, students analyze comics in depth; next, students are guided through the comic design process; finally, classes discover examples of opportunities to use comic art and writing throughout the instructional experience.

Step 1: Analyze Science Comics

Break students into small groups of two to five, and choose a science comic series, graphic novel, or age-appropriate illustrated non-fiction book that relates to a relevant topic or unit in your classroom. Explore and discuss the following questions with students around the selected illustrations:

- – What questions do you have about the topic conveyed in the comic?

- – What questions do you have about how the comic was made?

- – What connections can you make between the illustration and other topics or ideas that have already been covered in class?

- – What specific information did the author need to have ready before illustrating and writing about this topic?

- – How could you use this type of illustration to document your own experiments, discoveries, and adventures?

- – What characters, personas (avatars), logos, or color schemes make the illustrations consistent within this science comic series, graphic novel, or book? How does this comic compare to other comics?

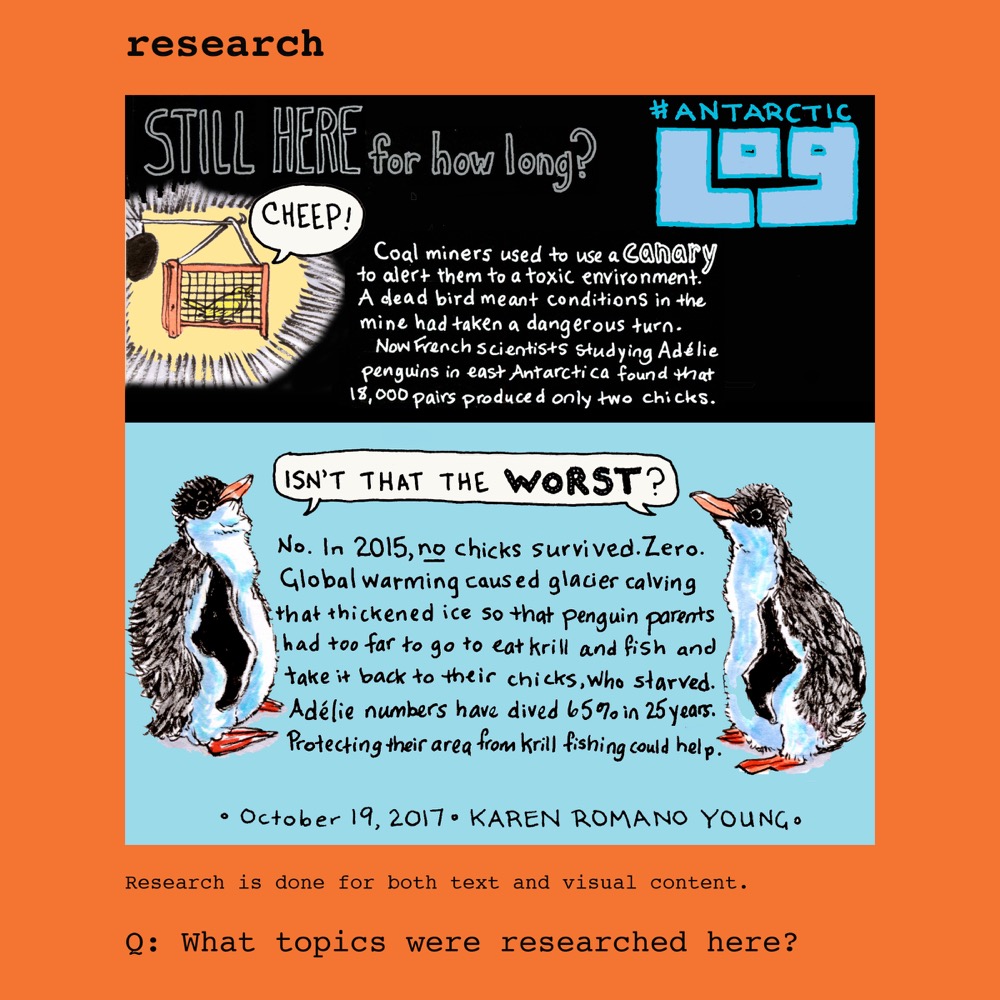

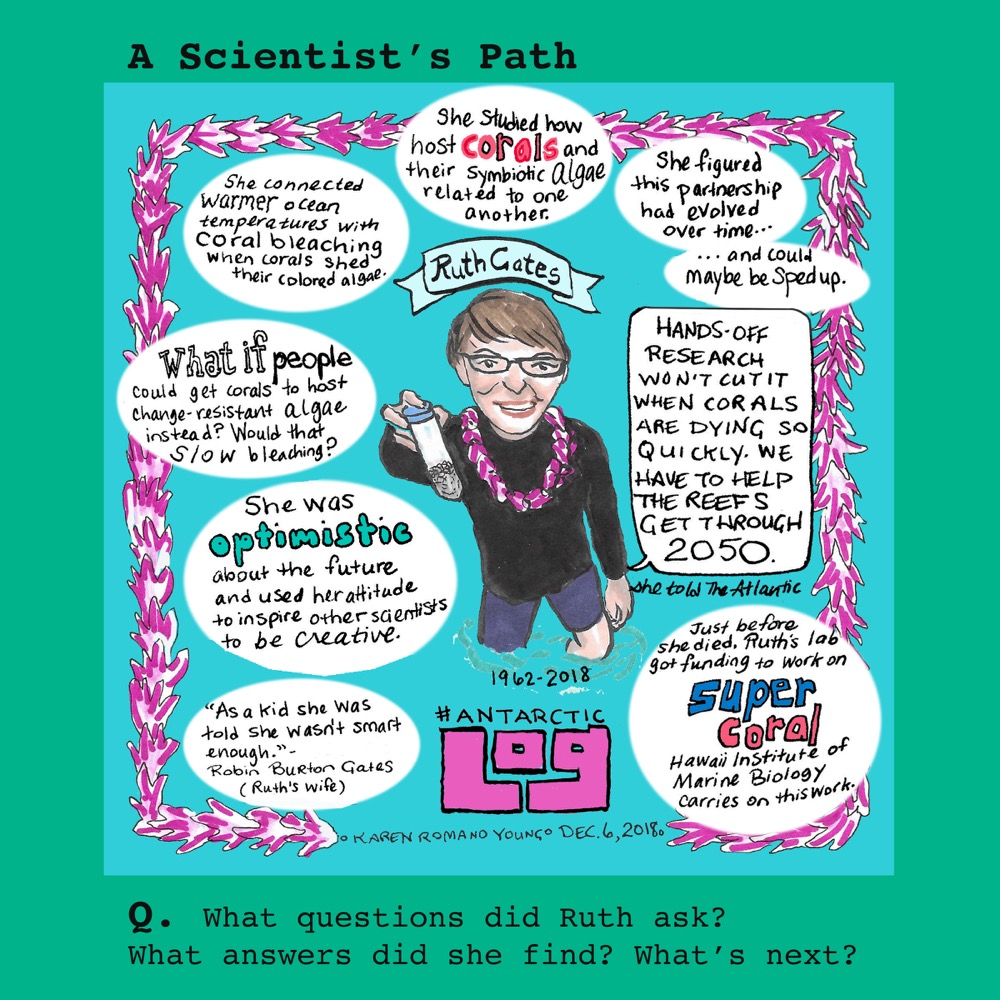

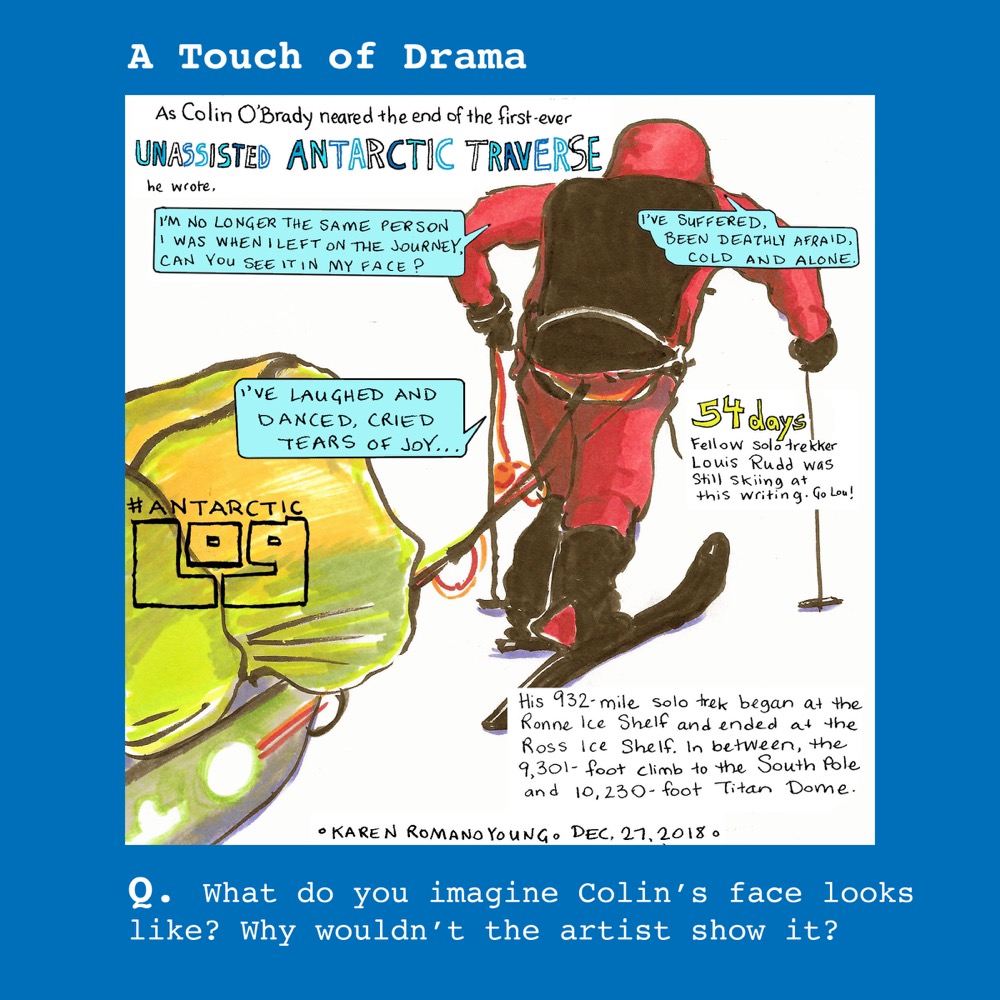

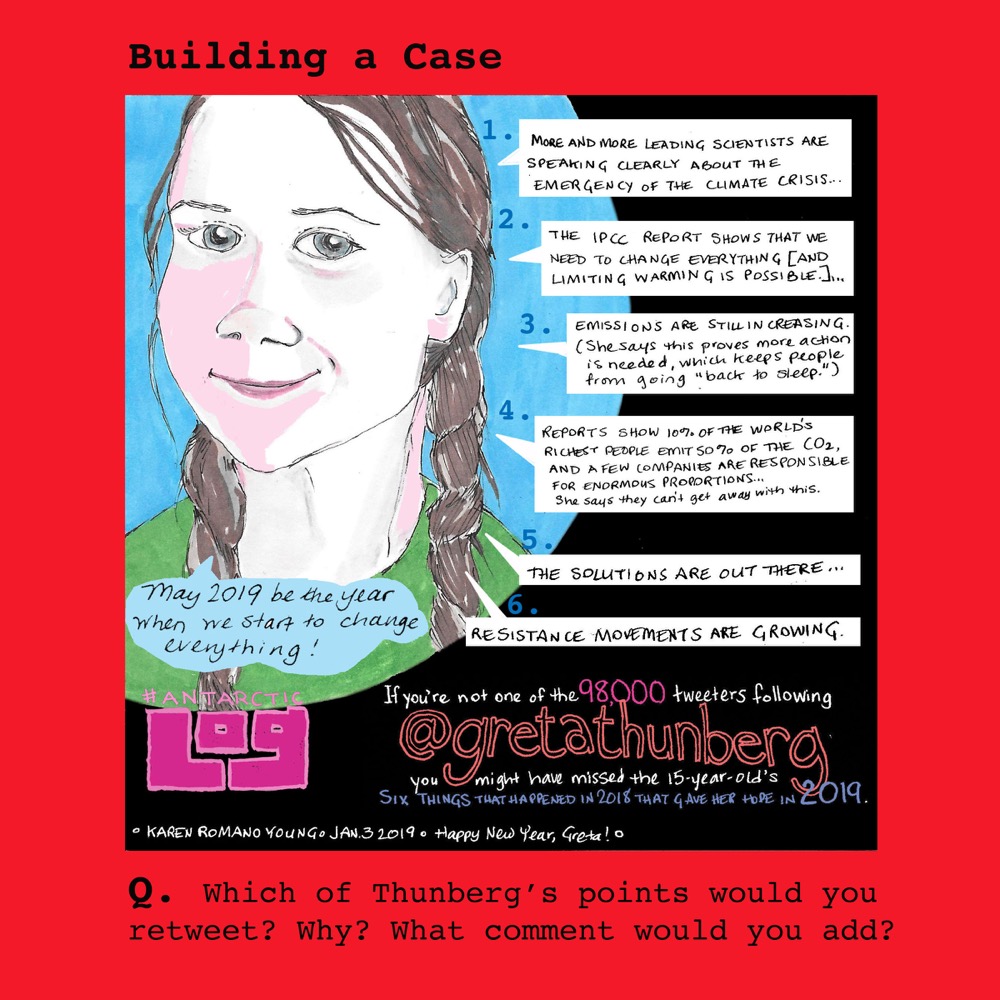

Take a peak at Young’s “Focus Log” which has annotations and discussion questions related to different features of her Antarctic Log comic series about Antarctic science.

Step 2: Design Science Comics

Creating graphic stories about science requires not only knowledge about the topic, but also a consistent style. Many illustrators and graphic artists stick to consistent color pallets, use the same font between comics, have a central character or “avatar” that represents the narrative voice, and even a logo–all of these elements help tie together the illustrations into a cohesive experience. Matching the comic style to the theme or topic of the comic is a great idea–perhaps a blue-water color scheme and a dolphin as an avatar for a marine science comic, or an orange-and-red color scheme and a thermometer as an avatar for a global warming comic!

Student Activity 1: Students will design a logo, avatar, font, and color scheme for their comic, working alone or as a group. Use this planning worksheet to design your comic and establish a comic style. Some tips as students begin designing:

- – Draw first with pencil, then with ink

- – Practice lettering, using different pens for titles or emphasis

- – Use color, but not too many colors at once, which can detract from the text

- – Think about a simple background that fills the white space but doesn’t distract from the text

- – Make sure that the logo is simple enough that it can be easily duplicated in future comics

Step 3: Experiment, Observe, Learn… And Illustrate!

Once students have established their comic book style, learning about the focus topic begins. Oakham Primary School integrates multimedia, comic books, powerpoint presentations, open discussions, and experiments in all their instructional units. Whether learning about the issues of climate change, ocean plastics, microbes, or space, unique student science comics can be used to capture and assess learning at multiple stages. For example:

- – Formative Assessment: Use comics to illustrate the perspectives of different experts during the research and learning phases.

- – Summative Assessment: Use a comic to explain a fundamental concept or idea

- – Claims-Evidence-Reasoning: Use comics to make a claim, and justify the claim with evidence.

- – Report Experimental Results: Illustrate the experimental setup, procedure, data, and data analysis, organizing the comic by phases in the research process.

Comics are inherently creative and fun for children. For educators, comics can be used to differentiate content and assessment for students at different levels of writing and reading. Explore the resources below for more examples of science comics as well as empirical evidence of the positive impact that comics can have on science learning.

Science Comics Further Reading

Comic Scholarship and Research

- – The Comics Grid, Journal of Comics Scholarship:

- – Cartoon Science, a blog and resources assembled by Matteo Farinella, Presidential Scholar in Society and Neuroscience at Columbia University and comic scholar

- – MIT’s Picturing to Learn Program

- – The Center for Cartoon Studies

- – Neil Cohn’s Visual Language Lab, Tufts University

- – Dunst, A., Laubrock, J., & Wildfeuer, J. (Eds.). (2018). Empirical Comics Research: Digital, Multimodal, and Cognitive Methods. Routledge

- – Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud

- – Making Comics, Scott McCloud

Articles and Publications

- – Why Comics Are More Important Than Ever, Huffington Post, 2014

- – Making Learning Visible: Doodling Helps Memories Stick, KQED, 2015

- – Comics in the Classroom, Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2017

- – Teaching with Science Comics, School Library Journal, 2017

- – Graphic Novels In The Classroom: A Teacher Roundtable, Cult of Pedagogy, 2016

Science Comics and Comic Artists

- – Comics creator Maris Wicks

- – Karen Romano Young

- – Maki Naro

- – Beatrice The Biologist

- – Bird And Moon

Common Core Standards

Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details; summarize the text.

Interpret information presented visually, orally, or quantitatively (e.g., in charts, graphs, diagrams, time lines, animations, or interactive elements on Web pages) and explain how the information contributes to an understanding of the text in which it appears.

This resource was developed by Joshua Kettle and Ashley Mills, teachers and science curriculum leads at Oakham Primary School, Tividale, England. Their aims have been to promote and improve science learning throughout the school and inspire the young scientists of the future.

Meet the Writers

About Karen Romano Young

@DoodlebugKRYKaren Romano Young is a writer, illustrator, polar explorer, and deep sea diver. She is the author of more than two dozen books.

About Oakham Primary School

@oakhamprimaryOakham Primary School is situated in Sandwell, West Midlands England. It is a two form entry school, with 482 children from a broad mix of socio-economic backgrounds.