The Origin Of The Word ‘Seaborgium’

For 20 years, it was known simply as “element 106.”

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

Science Diction is a bite-sized podcast about words—and the science stories behind them. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts, and sign up for our newsletter.

1953; Officially adopted 1997.

Seaborgium gets its namesake from—you guessed it—the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Glenn T. Seaborg. But both the name and the discovery of element 106 caused a major controversy.

In 1974, two teams of researchers—one at the University of California, Berkeley and the other in Dubna, Russia—hit the jackpot. Within three months of each other, the two teams had discovered the same element via different methods. For 20 years, neither was able to reproduce their findings, largely because the new element was incredibly short-lived, and decayed within seconds. Without reproducibility, the element could not be officially “discovered,” so for two decades it was known simply as “element 106.”

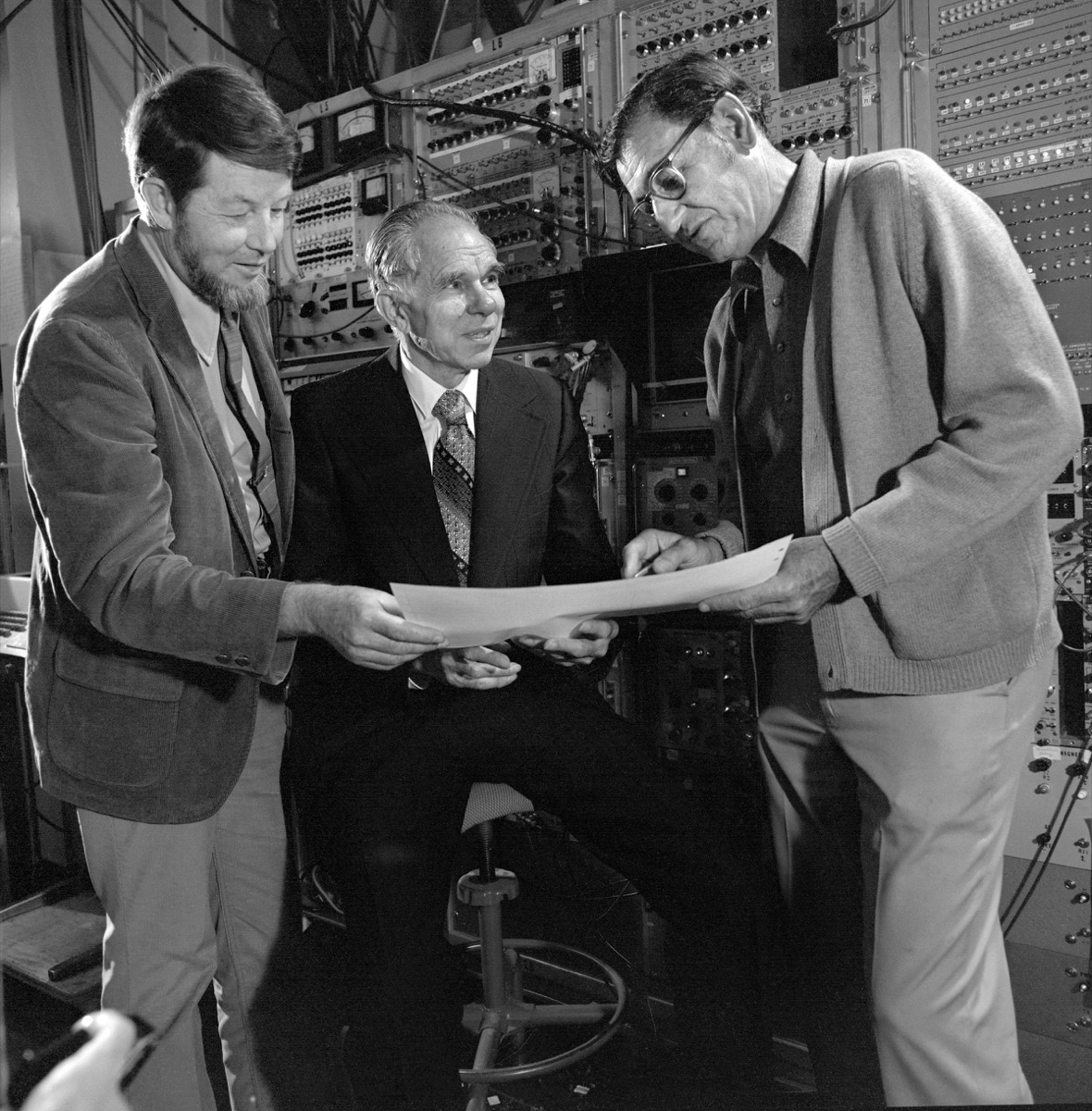

In 1993, the American team’s experiment was finally independently confirmed, and the team clinched naming rights. But no fewer than eight scientists were involved in the discovery on the team, and there were a lot of suggestions—from naming it after Isaac Newton to the nation of Finland. The suggestions flew back and forth until the physicist Albert Ghiorso awoke in the middle of the night with an idea.

After getting approval from the other members of the team, Ghiorso set up a meeting with his old friend and colleague, Glenn T. Seaborg. Seaborg wasn’t directly involved in the project, but was a Nobel Prize-winning physicist instrumental in the discovery of plutonium, and he was the associate director-at-large of the Berkeley team’s lab. When the meeting arrived, Ghiorso brought a folder called the “Element 106 Story,” handed it to his friend, and watched Seaborg open to the first page with the name of the proposed element.

“He was clearly astonished—and pleased too,” writes Ghiorso. “I felt that in the great panoply of names that had already been picked for the heavy element region, the name ‘seaborgium’ would be of equal worth to curium, einsteinium, fermium, mendelevium, lawrencium, rutherfordium, hahnium, nielsbohrium, and meitnerium.”

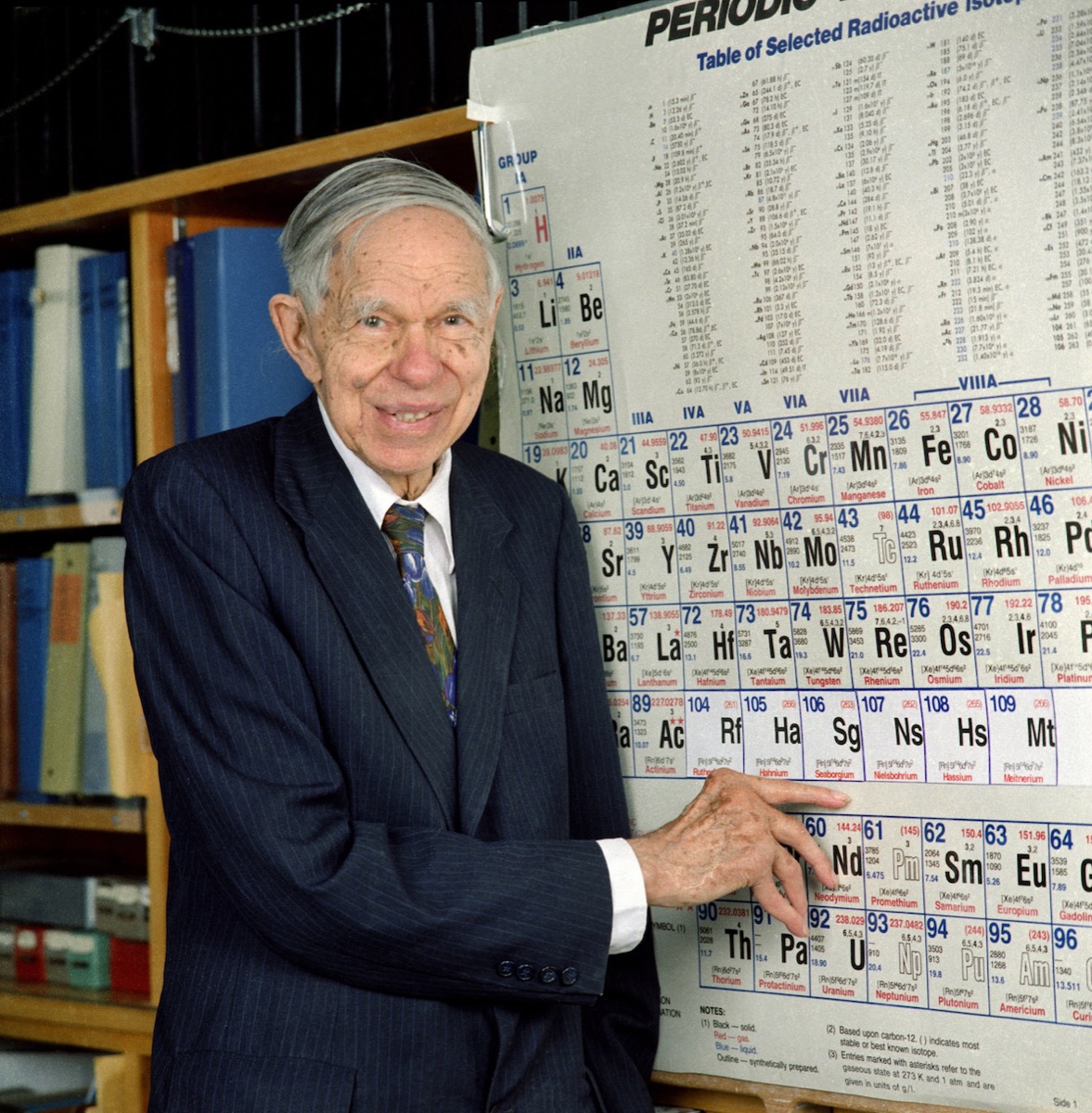

There had been rumblings since the 1950s to name heavy elements after Seaborg, to honor the role he played in the discovery of transuranian elements, or elements that fall after uranium on the periodic table. It had never amounted to more than suggestions before, but with element 106, Seaborg would be officially enshrined in the elemental hall of fame.

One problem: Seaborg was still alive. Per the tradition of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), which has final approval on terminology for everything from standardizing units of measurement to naming new elements, elements may be named after a mythological concept or characters, a mineral, geography, a property, of a scientist. But at the time of Ghiorso’s proposal, no element had been named after a scientist that was still alive. (Einsteinium and fermium, while proposed while their namesakes were still living, were classified at the time and the names were not made public until later.)

The IUPAC shot down the proposed name.

“He was blindsided, and a little hurt, by the controversy the proposal engendered,” writes Seaborg’s son Eric. “Naming an element for a living person was not quite as radical as some said—he and his team had proposed the names einsteinium and fermium while those eminent scientists were still alive. And frankly, he didn’t quite see how dying would make him that much of a better person.”

To top it all off, the seaborgium uproar found itself smack in the middle of a swirling international controversy around naming several elements. Over the course of two decades, researchers in the U.S., Germany, and Russia had created a slew of ultra-heavy elements—elements 104-109—using nuclear accelerators. And while the atoms created from these collisions diminished within seconds, the name of the element would last as long as the periodic table. And by the 1990s, the IUPAC was trying to keep everyone happy.

Thus ensued a dizzying series of naming switcheroos and proposed—and botched—compromises by the IUPAC. Try to keep up.

Have we lost you yet?

The back and forth went on for years, until a compromise was finally reached in 1997. In the end, rutherfordium was restored to element 104. Dubnium was here to stay, but ultimately assigned to element 105 instead. Neither Otto Hahn nor Frederic Joliot-Curie have gotten their day (yet).

And with element 106—after heated discussion and lobbying—seaborgium became the first element named after a living scientist.

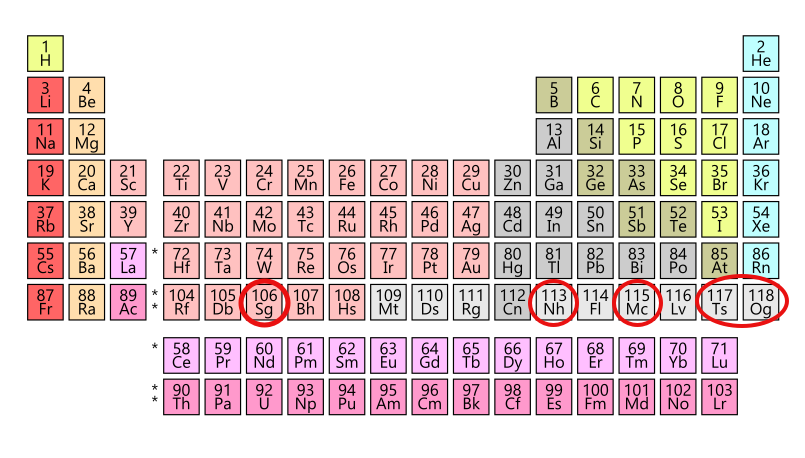

Let’s say you discover an element. How do you name it? After confirmation of discovery, researchers may suggest a name to the IUPAC Inorganic Chemistry Division. Part of that process is a five-month public review period. For example, in 2015, there were four elements confirmed: elements 113, 115, 117, and 118, rounding out the 7th row of the periodic table. And while the team who “discovered’ the element gets naming rights, the public are welcome to chime in, too.

Although merely invited to comment on the already-proposed names, that didn’t stop many people from suggesting their own names for elements 113, 115, 117, and 118 during the public review process in 2016. Suggestions ranged from renowned chemists in the past who don’t have an element to their name (an internet petition to name one of the elements “Levi,” after chemist and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi, amassed signatures from 3,000 professional scientists and supporters), to recently deceased musicians like David Bowie, and others “(semi) jokingly” proposed names like Tattooine and Taxpayeron. In addition, the IUPAC received essays from 75 students weighing in on what name should be bestowed upon the new elements.

After much discussion, in 2016 element 118 became the second-ever element to be named after a living scientist—and it just so happened to be named after Yuri T. Oganessian, who is now the scientific leader of the same Dubna lab that co-discovered seaborgium. The other three new elements also followed conventional naming standards: Moscovium (element 115) and tennessine (element 117) honor their respective regions where important research was conducted, and nihonium (element 113) is one way to say “Japan” in Japanese, and is the first element in history to be discovered in and named after an Asian country.

“International unions have to serve all the world for understandable names and principles, and the same goes for element names,” says Jan Reedijk, a retired professor of chemistry, and past president of the IUPAC division that dealt with naming. “The IUPAC community could overlook something…. it could be that some of these names have a bad meaning in a different language, for instance.”

Oganesson, moscovium, tennessine, and nihonium completed the 7th row of the periodic table. But are there any more elements to find? Probably. And Reedijk says discovering new ones is in the hands of physicists and chemists.

“The physicists have to have the equipment, and they make new elements by bombarding the certain specific isotope of one element on the surface of another element,” he says. “These isotopes that they bombard with are quite often highly unstable and need to be purified. And the purification of these bombarding particles has to be done, has always been done, and will always be done by chemists and chemical separations.”

And as for naming those future elements, Reedijk suggests keeping a database of the names proposed by the public. In the future, one just might fit.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.