How Climate Change Ruins Snowflakes

4:19 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story, by Clarisa Diaz, originally appeared on Gothamist and WNYC.

As another erratic winter draws to a close, it’s time to consider a lesser-known possible effect of climate change: misshapen snowflakes.

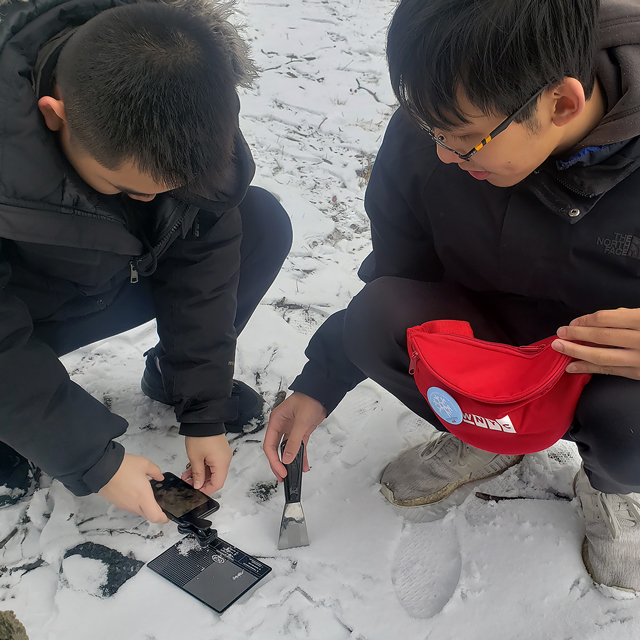

Last winter, WNYC first reported on the scientists at Columbia University’s Earth Institute who are studying how warmer winter air is changing the way snowflakes form, but rather than wallow in sadness and nostalgia, we spent the interim period developing a snowflake photography and snowpack measurement kit that anyone can use to help contribute to the research project. The scientists need way more data than they can conceivably collect on their own. That’s where you come in. Citizen scientists unite!

We partnered with two local high schools, Bronx Science and the New York Harbor School, to make sure our kit was, in fact, easy to use, and to offer the teachers a hands-on project to help students learn more about climate change.

“It works, it fits perfectly with what we’re talking about right now, and just how this might just be an indicator of some kind of climate shifting,” said Ed Wren, a science teacher at Bronx Science.

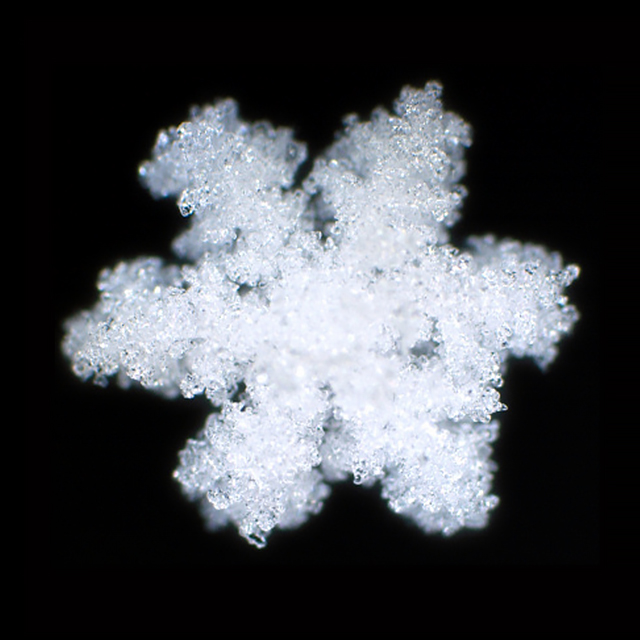

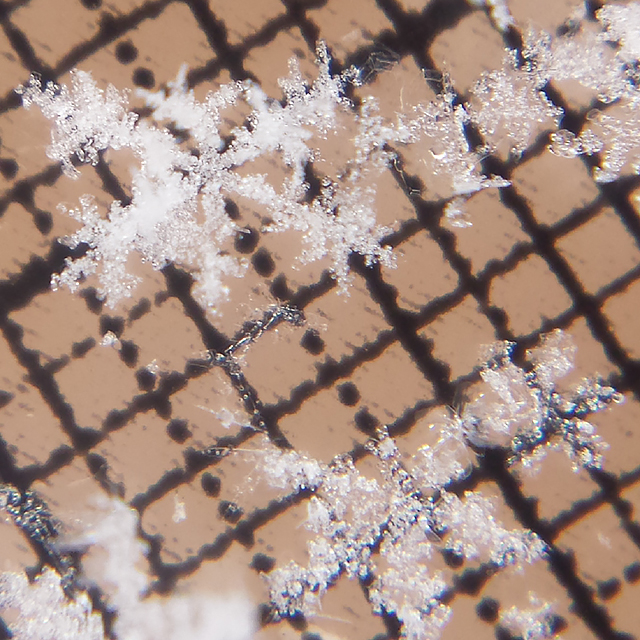

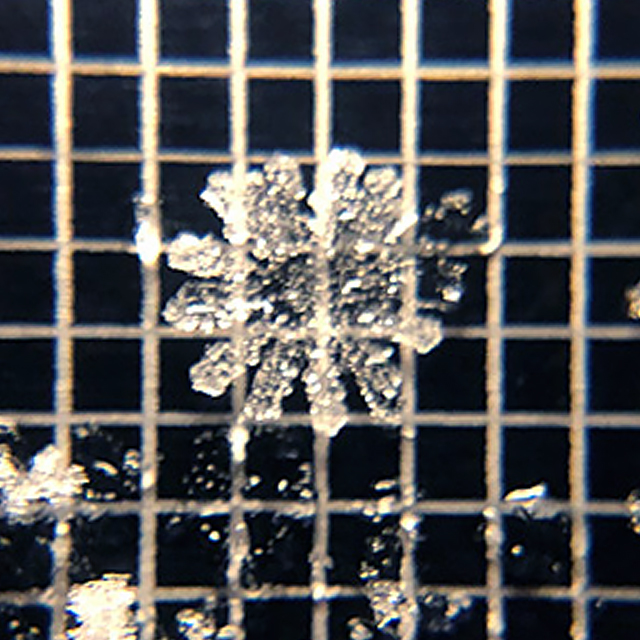

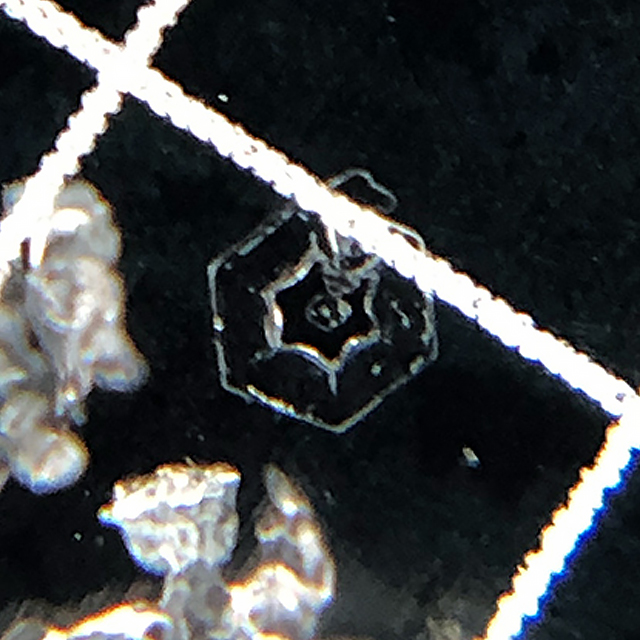

For those of you who missed the story last year, here’s the situation. As we can all attest, climate change is creating more fluctuating temperatures. Normally, snowflakes form high up in the atmosphere, and crystallize into their pretty structures as they pass through cold layers of air. But with warmer temperatures, snowflakes can partially melt on their way down. There’s more water in the air these days, and it acts like a glue that can glom onto the snowflakes, covering them with little ice pellets. Add in the wind and the snowflakes can smash together, turning into mega snowflakes. See for yourself:

To add insult to injury, after these snowflakes land they melt faster because they’re less able to reflect light. This has serious implications for flooding and hydrology as well as spring vegetation. When melting occurs normally, the nutrients in the snowpack are absorbed into the soil. Not so when it melts away really fast.

Our snowflake photography kit comes with everything you need to take your own pictures of snowflakes and measure the snowpack near you, including a microscope that attaches to your smartphone! (You also get a handsome red WNYC fanny pack!) Maybe you’ll be traveling to a frozen tundra soon? Maybe you’ll grab your kit now and practice photographing sugar crystals so you’ll be ready next winter? Heck, it may snow tomorrow. It’s hard to tell these days.

Despite the gravity of the situation, it’s actually really fun to photograph snowflakes.

“It’s pretty fun, because we are an environmental science course, it’s more interactive,” said Lucy Jin, a senior at Bronx Science. Lucy’s classmate Ellen Ren added, “It really makes you aware of your environment. And to see it before our eyes, it’s even better.”

According to Dr. Jared Entin, a manager for the Terrestrial Hydrology program at NASA, scientists use satellite footage and drones to get a high-level view of snow, but they also need data about what’s happening on the ground.

“We need people out there taking all sorts of different observations,” he said. “What NASA is doing at this point is trying to move beyond just ‘Is snow on the ground or not?’ and start to answer deeper questions like ‘How much water is actually stored in the snowpack?’”

WNYC worked with Dr. Marco Tedesco, a polar scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and his team to design the kits and the training materials. For the past couple of years the team has been involved in several field experiments to look at snow properties in the New York region.

“I think it’s very important for New Yorkers to understand the importance of snow not only for recreational purposes, but also for other purposes. Studying snow can tell you a lot about the history of the snowpack, can tell you a lot about where the snowflakes come from, what happened when they were falling,” Tedesco said.

We made a website with Columbia that includes how-to videos and instructions for contributing your photos and data to the project. You can purchase your kit here.

Now get out there and contribute to science!

For more on this project, listen to reporter Clarisa Diaz’s segment on WNYC:

Clarisa Diaz is a reporter and designer at WNYC in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is Kit Yari.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO

SPEAKER 3: Saint Lewis Public Radio

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News

IRA FLATOW: Local science stories of national significance. Well, it may feel like spring in some parts of the country but some scientists are still, well they still have snow on the brain. And it turns out that besides shaking up when and where it snows, climate change is also messing with the shapes of our snowflakes. And one local citizen’s science project is asking you to help document the process.

Here with more about why climate change makes for weird snowflakes, WNYC reporter in New York and designer, Clarisa Diaz. Hi, Clarisa.

CLARISA DIAZ: Hi, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about this. I get that climate change would affect when it snows and where. But we’re talking about the snowflakes themselves being misshapen.

CLARISA DIAZ: Yeah. So, I think as we can probably feel, climate change is creating these fluctuating temperatures. So we have cold weather followed by warm weather followed by cold weather. It’s basically like this yo-yo effect. But for a snowflake to form, it forms high up in the atmosphere. And ideally, it needs to pass through consistent layers of cold air in order to fully crystallize.

So if you have warmer layers of air in there, basically three things can happen to a snowflake. The first is that a snowflake can only partially form. And basically partially melts because of the warmer air. And this is actually known as rounding. And basically the structure, the intricacy, of that snowflake is less defined.

And the second thing that could happen is that because the air is warmer you actually have more liquid water in the air. So you get these droplets of water and those are called rime. And they will actually act like a glue and they’ll stick onto the snowflake. And if you get a covering of rime, or covering of these droplets, it’s known as graupel or soft hail.

IRA FLATOW: So why do these snowflakes need to be studied? What are you going to learn from that?

CLARISA DIAZ: Yeah. So one other thing that happens is they kind of smash together in the wind. So they’re less able to reflect light. And the important thing is not only what happens in the atmosphere but when it actually goes on the ground it creates this winter snowpack. And if the snowflakes are less able to reflect light then that means the snowpack is less able to reflect light too. So everything just melts faster.

And that actually can have implications for the hydrology of the region. The water that goes into streams and reservoirs, as well as the nutrients that that snowpack contains that’s absorbed, usually gradually from the soil, by the soil and produces nourishment for spring vegetation.

IRA FLATOW: So you want our listeners to pitch in on a project. Tell us about that.

CLARISA DIAZ: Yeah. We worked with Dr. Marco Tedesco at Columbia University’s Earth Institute and his team and we basically followed them to understand how they collect data. And we worked with them to create this snow kit that anybody can use to kind of take photographs of snow flakes and see how they’re changing. And also measure the depth of snow in their local area.

IRA FLATOW: Here’s Jared Entin, manager of terrestrial hydrology program at NASA talking about it.

JARED ENTIN: When you think about these models that we use they need a lot of what we call validation. So we need people out there taking all sorts of different observations. What NASA’s doing at this point is also trying to move beyond just is snow on the ground or not. And start to answer deeper questions like, how much water is actually stored in this snowpack.

IRA FLATOW: So you want our listeners to actually go out and do this?

CLARISA DIAZ: Yeah and we actually have the snow kit all designed.

IRA FLATOW: What is a snow kit? You get a kit?

CLARISA DIAZ: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And what do you do?

IRA FLATOW: You basically, it has a clip-on microscope that clips onto your smartphone and that allows you to take microscopic images of the snowflakes. It’s really cool to see that.

IRA FLATOW: And then you email them somewhere?

CLARISA DIAZ: Yeah. We have a website that we built with Columbia University where you can get all the resources that you need in order to use the kit as well as upload data for the scientists.

IRA FLATOW: That’s cool.

CLARISA DIAZ: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Get out there before the snow melts. Get out there while there’s still snow. There is actually more on our website. If you want to do this, it sounds cool. sciencefriday.com/flakes. sciencefriday.com/flakes. Clarisa, thank you.

CLARISA DIAZ: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Taking time to be with us today. Clarisa Diaz, a reporter and designer at WNYC.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.