How Jumping Spiders Avoid Becoming A Tasty Snack

16:24 minutes

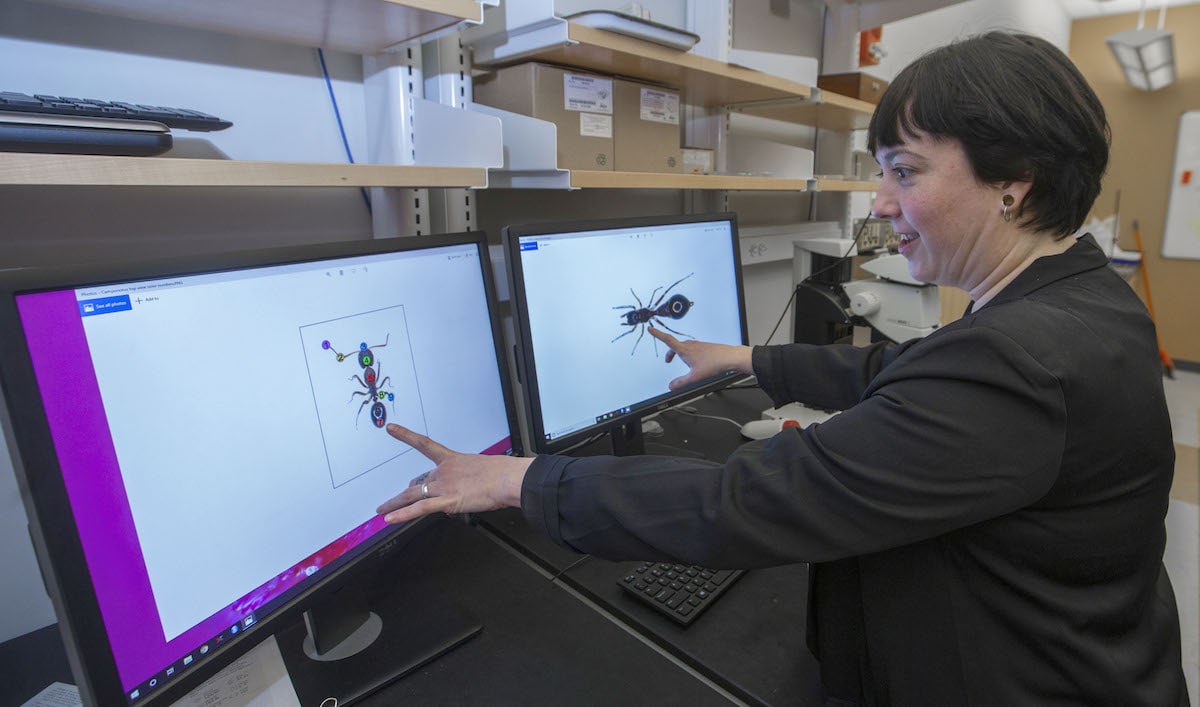

Jumping spiders are crafty hunters, but sometimes they need their own disguise to avoid their own predators. Biologist Alexis Dodson studies Synemosyna formica, a species of jumping spider that avoids detection by mimicking ants. They have even changed their characteristic way of movement: The species of jumping spider lost its ability to jump in order appear more ant-like.

Sometimes, predators can be your own mates—male jumping spiders becoming a female’s meal if their courtship displays don’t impress. Entomologist Lisa Taylor looks at how male jumping spiders use coloration to signal to females that they’re a promising mate rather than a tasty snack. Dodson and Taylor talk about what jumping spiders can tell us about tell us about the evolution of coloration and communication in the natural world.

View these jumping spiders and their tricky, vibrant predator-evading techniques below!

Alexis Dodson is a Ph.D. student in Biological Sciences at the University of Cincinnati in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dr Lisa Taylor is a behavioral ecologist in the Entomology and Nematology Department at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Why would a spider try to imitate an ant, I mean, contort its body, its antennae, slouch down, do its best to be something that it’s not? Well, that’s what certain types of jumping spiders do.

Here to answer that question is Alexis Dodson, PhD candidate in biological sciences at University of Cincinnati and Dr. Lisa Taylor, research scientist in entomology and nematology, University of Florida in Gainesville. Welcome to Science Friday.

ALEXIS DODSON: Hi. Thank you.

LISA TAYLOR: Thanks for having us

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Taylor, there are 6,000 species of jumping spiders? Obviously, they jump, but do they build webs? And what makes them a distinct group of spiders?

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah. So jumping spiders are really common. Like you said, there is more than 6,000 species. They’re found on every continent except Antarctica. So all of your listeners have these guys in their backyards.

They’re, yeah, they’re really interesting because they jump. And they’re also really interesting because they have these really big eyes that make them pretty adorable as well. They don’t build webs. They don’t build the typical orb web that most people are familiar with.

They do have silk, so they build. They use silk to build little retreats, a little nest that they lay their eggs in and that they hang out in at night. But, yeah, they’re everywhere. And they’re really interesting. And most people have them in their yards.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s get into how interesting they are. Alexis, you studied a jumping spider that is such a good mimic that it looks more like an ant than the actual ant does.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yes. So what we actually found is that the– so there are adults and juveniles of the species that we looked at– and we have found that the adults more closely resembled their model ant species, which is in Camponotus, then they did juveniles of their same spider species. And the same was true for the juveniles who mimic an ant in the genus Crematogaster. So it’s pretty crazy. They look more like ants than each other.

IRA FLATOW: OK. So why do they want to do that?

ALEXIS DODSON: Well, so myrmecomorphy, aside from being one of the more fun words to say in the English language, is a really widespread strategy. And the reason the animals do this, why they want to mimic ants, is that ants are– they’re not great to eat. They bite. They sting. They come in numbers, so they can swarm you.

And when it comes down to it, they’re quite small and not very nutritious, so it’s often not worth the effort. So it makes sense that an animal that’s small and maybe nutritious and not as formidable might want to mimic that to gain the protection from predation. Another reason could be that they want to eat ants themselves and maybe not reveal themselves to their prey.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Speaking of interesting stuff, our number, 844-724-8255. You can get in on the conversation about jumping spiders, 844-724-8255 or you can tweet us @scifri. They have also, Lisa, they have all sorts of predators. And sometimes the predators can be its own mate, as we just heard. Females eat males.

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah. Yeah. So jumping spiders have two challenges. So one is to avoid getting eaten by bigger things like birds and just other large animals. And then if you’re a male jumping spider, you have an additional challenge and that’s to not get eaten by the female who you’re trying to court. All jumping spiders are voracious predators.

And so if you’re a male jumping spider, you have to very carefully approach a female and put on a good show, impress the female. Let her know that you’re the right species and you’re willing to mate, and also that you’re not going to be a very appealing meal. So it’s a pretty big challenge that a lot of other animals don’t have to face when they’re courting.

IRA FLATOW: After their courting is finished, does the female eat the male?

LISA TAYLOR: So sometimes. So sometimes she’ll attack and eat the male before he’s done courting. Sometimes she’ll attack and eat the male after he’s already mated. It just kind of– yeah, things play out differently almost every time.

So one thing that I didn’t mention that’s really unique about jumping spiders is they have a lot of really bright colors. So they’re really interesting ant mimics like the ones that Alexis studies that look like ants. And then there are also a lot of other jumping spiders that look more like spiders except they have really elaborate colors that kind of rival the color patterns of some of the more elaborate birds.

So there are actually jumping spiders called peacock spiders that have really bright coloration on their abdomens. And they actually wave their abdomens around at females. And there’s a lot of, yeah, basically, males put a lot of effort into their courtship displays. Some of them, so they’re really colorful. Some of them also sing and dance, actually produce sounds that travel through the substrate for the female.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. I know, Lisa, because you study this, you study it very carefully, you actually dress up termites in different color coats to test this?

LISA TAYLOR: That’s true. Yeah. So one of the main hypotheses that we’re testing is this idea that perhaps maybe some of these colors that males put into their display– so one of the species we spend a lot of time studying, it’s very common for males to have really bright red faces. In other closely-related species, the males have black and white, these bold black and white stripes on their faces– so one of the ideas that we’re trying to test is that perhaps these colors have evolved on the males in order to avoid getting eaten by the females.

And so one way we can test this is we can ask females what kinds of things they like to eat. So that’s where the termites come in. So we’ve given females lots of choices between different termites that have been painted different colors, who have little capes with different patterns on them.

And so what we know, in general, from a bunch of different species is that, in general, the species that can see red don’t like to eat the color red. So they’ll choose a lot of other colors over red. And they’ll also choose a lot of other colors over black and white stripes. So that kind of lends some initial support to the idea that maybe these colors have evolved on male faces to help them avoid getting eaten by females.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. 844-724-8255. Let’s go to the phones to Kate in Owensboro, Kentucky. Hi, Kate.

AUDIENCE: Hey, how are you, guys?

IRA FLATOW: Hey, there.

AUDIENCE: So I have a question about jumping spider ownership. I was wondering if it was ethical or not? My daughter is really into spiders. She’s three. And so I was wanting to get her into spider husbandry and ethical spider ownership.

And we were thinking about maybe starting with a small native jumping spider that’s native to this part of Kentucky in case it gets out. Is it ethical? Would we be able to keep it in an enclosure? Or would it be better to catch and release?

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah. So I have a four-year-old also who loves watching jumping spiders. And I mean, so we have a lot of them in the lab that we observe and collect data on. But I think as just a normal citizen who’s maybe not doing research on them, I would say, to me, it seems ethical to take them into captivity for short periods of time as long as you’re taking good care of them and giving them all the resources that they would have in the wild.

So pay attention to, or learn a little bit about the species before you take it in and start taking care of it. Provide it with food. So they only like to eat live prey, so it’s a bit of a commitment then you have to go out and catch stuff to feed them. And you have to give the spider water occasionally.

And I think it’s probably a good idea to not keep them in captivity forever, but maybe just keep them, watch them a little while. Give them a little bit of extra food, maybe even more than they would get normally. And then send them on their way and they’ll go back out into your garden and help eat some of your pests. Did I leave anything out, Alexis, about things that spiders might need?

ALEXIS DODSON: Oh, no. I actually, absolutely agree with you. I would add to that that just the idea of doing the research to figure out what the animal needs and how to best take care of it is just a really great way to learn about their natural history and to get your child engaged in the ecology of these animals and what they do need, and what they hunt, and how they live. And so it’s a fun exercise in and of itself. But I think, absolutely short periods of time is great.

IRA FLATOW: Kate, do you think you’re going to do it? Kate, are you there? Oh, Kate’s gone.

AUDIENCE: I’m right here.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, are you going to go ahead and try this?

AUDIENCE: Yeah. I mean, we’re really into– I mean, she’s really into the Phidippus– I can’t remember what the second word was, but it’s like the royal jumping spider– the regal jumping spider.

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah.

AUDIENCE: The Phidippus regalis–

ALEXIS DODSON: Yeah. Phidippus regius.

AUDIENCE: –which is native to this area.

LISA TAYLOR: Regius.

AUDIENCE: And it’s a pretty decent size spider, so she’ll be able to see it better. So, yeah, I mean, we might– if we come across one in our garden this year, we might bring it in and spoil it for a little bit, and then–

LISA TAYLOR: Yes

AUDIENCE: –let her go.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yeah. I mean, back to the question of ethics, I think if you’re raising a 3-year-old to appreciate nature and appreciate that these are– and take a closer look at these little creatures, I think she’ll probably grow up to be an adult who cares about nature and science. So–

LISA TAYLOR: Absolutely.

ALEXIS DODSON: –so I’d say go for it.

LISA TAYLOR: I think you’re doing a good thing there.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Let me go to the phones to Rick and Charlotte from Bridgeport, Connecticut. Hi, Rick, Charlotte.

AUDIENCE: Hi, Ira. How you doing?

IRA FLATOW: Hey, there. Go ahead.

AUDIENCE: So I have Charlotte in the car with me, we’re driving home. And I really appreciate that last caller. I hadn’t even thought about that and I think we might do that, too. Of course, my daughter loves spiders.

And one of the questions that she always asks about whenever we talk about a new spider is, how much does the spider bite hurt humans? So in terms of jumping spiders, because I know that most spiders don’t bite, but if they did, how bad is the bite?

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Do they bite, Alexis? Yeah, Lisa?

ALEXIS DODSON: Yeah.

LISA TAYLOR: So they’re capable of biting, so they do have fangs. Most of them won’t bite you. I’ve never been bitten by a jumping spider and I’ve handled thousands of them. I mean, usually, they don’t bite you to go after you. They just might bite you if you squeeze one in your hand and it has nothing else to do but bite.

So I can’t comment on how much it actually hurts. But they don’t have a venom that interacts with our system in a negative way, so it wouldn’t be a big systemic effect or a lesion or anything. It probably would just feel like getting pinched by something pointy. I don’t know, Alexis, have you ever been bitten by a jumping spider?

ALEXIS DODSON: No. No. I’ve been working with spiders for over four years now and have not met anybody that I’ve worked with that’s been bitten by spiders, nor have I been bitten myself.

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah, same here.

ALEXIS DODSON: And, yeah, and I think the interesting thing about a lot of spider venom, and then this isn’t true for all spider venom, so you should do your research, but that a lot of it doesn’t impact vertebrates. So–

IRA FLATOW: Really?

ALEXIS DODSON: –it’s meant for invertebrates. Yeah. So there are some spiders that are dangerous to humans, the black widows and your brown recluse, and things like that. But many spiders, the puncture will probably hurt if they can break skin, but some of them can’t even do that.

IRA FLATOW: Is it surprising to you, we just had two callers on with kids who certainly don’t have arachnophobia? I mean, they are not scared of spiders.

ALEXIS DODSON: Not at all, that doesn’t surprise me a bit. Children are amazing in that way. They really enjoy the natural world and they haven’t yet– many of them haven’t yet learned some of those fears that we get of strange-looking animals or animals that might be spooky like spiders.

LISA TAYLOR: I told someone what I did sitting next to someone on an airplane and they said, oh, you study spiders all day? You’d get along really well with my son, he’s three. And I thought, yeah, actually, I probably would.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yeah. Yeah, we hear that a lot. Oh, my kid loves spiders. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go back to the ant-looking spider.

LISA TAYLOR: OK.

IRA FLATOW: I mean, how do the ant-looking jumping spiders communicate to the other spiders? Do they say, psst, I’m really a spider?

LISA TAYLOR: So yeah, they whisper. No. So these animals exist in these three-dimensional environments. And so we were actually trying to figure out, so if these guys are looking so much like ants, how are they then doing this essential thing, which is communicating to conspecifics that they’re there and they’re ready to mate?

And one of the things that we found when we were doing this morphological analysis of these animals– so they look a lot like ants from up above. But then when you look at them from the side perspective, so a lateral perspective, you find that the adults actually adopt a more spider-like profile and move away from that very ant-like profile.

This doesn’t happen for the juveniles. So what you’re seeing here is just sort of a change in the ratio of selective pressures where a lateral selective pressure is saying, I need to be recognized by conspecifics. And there are predators and they are going to try to eat me, but this is important, too, so I need to communicate in some way.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Talking about jumping spiders. Let’s go to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Gail, hi. You’re on Science Friday.

AUDIENCE: Hi. Hi, there. I lived in Costa Rica for many years. And one of the most amazing sights I ever saw, in terms of predator-prey observations, was when I was sitting with friends at about 6,000 feet elevation in a Rancho style open-sided restaurant, we were watching a beautiful morpho butterfly flying by, just admiring the gorgeous blue colors of the morpho.

And suddenly, it smashed to the ground. It just fell to the ground like a torpedo had hit it. And I ran over to see what had happened. And it was a jumping spider about the size of a large chocolate chip cookie that just landed on the spider. It came out of the rafters of the restaurant and attacked it and proceeded to eat the morpho.

LISA TAYLOR: I bet it did.

AUDIENCE: So it was really amazing.

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah, they’re amazing.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

LISA TAYLOR: They’re like cats in that way. They hunt, and they stalk, and they pounce.

IRA FLATOW: And you can find them anywhere. Anybody can find them in their backyard?

LISA TAYLOR: Yep. You can find them at the top of the Himalayas. They are everywhere.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yep. I find them in my office all the time just kind of like free range, not because they escaped from the lab, but just because they came in through the windows.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Lisa, you talk about the psychology of spiders. Do you mean in the same way we talk about it for humans? Do spiders plan, try to trick each other?

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah. Well, so they, in a sense, yes. So one of the things we’ve been thinking about a lot, in terms of trying to understand why males have all these really elaborate displays, is we think that what they’re actually trying to do is exploit the female psychology. So females are predators and so they are always searching for prey.

And so they’re like– their prey searching intersects with their mate searching– and so they’re kind of like always– basically, they’re always in predator mode. And so we think that males, maybe by putting some of these colors on their faces, are kind of taking advantage and tapping into that psychology and trying to deceive females a little bit.

Because if they know that females might hesitate a little bit before attacking something that’s red or striped, then it’s not necessarily that the male is trying to look like something that’s red and toxic, or something that’s striped and toxic, but it might just trick the female a little bit so she pauses a little more before attacking.

IRA FLATOW: It sounds to me like a spider is a lot smarter than– if it’s able–

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: –to be cunning and think of tricks– than we give it credit for.

LISA TAYLOR: Oh, yeah, definitely. So part of our research involves actually training spiders. So to test some of these ideas about how females respond to colors on males, we also have to train them to have particular preferences and aversions to color. And so we can actually train them in the lab.

We give them red food that tastes really great. And we give another group red food that tastes bad. We can actually train one group to prefer red and the other group to avoid red. And so we can actually kind of take advantage of their smarts to learn a little bit–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

LISA TAYLOR: –about why they do what they do.

IRA FLATOW: You know, we talk about cephalopods all the time and how smart they are. And then we think of the octopus as being really smart. But this is like the land-based octopus brain.

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah. Yeah, they are. They’re like tiny octopi. They have eight legs too.

ALEXIS DODSON: Eight legs and all, yep.

IRA FLATOW: I think we made a match.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yep.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I want to thank you both for taking time to be with us today. Alexis Dodson is a PhD candidate in biological sciences at the University of Cincinnati. Dr. Lisa Taylor is a research scientist in entomology and nematology.

LISA TAYLOR: Yes. Yeah, thanks for having us. It was fun.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

ALEXIS DODSON: Thank you so much. It was great.

IRA FLATOW: We learned a lot. We connected with a lot of people and their spiders. Dr. Taylor’s at the University of Florida in Gainesville. And you can see photos of these spiders. We have them there, the spiders we talked about. They’re up on our website at ScienceFriday.com/jumpingspider. Thank you. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

ALEXIS DODSON: Yeah, thanks

LISA TAYLOR: Yeah.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.