A Tantalum Bullet For Asteroid Research

6:46 minutes

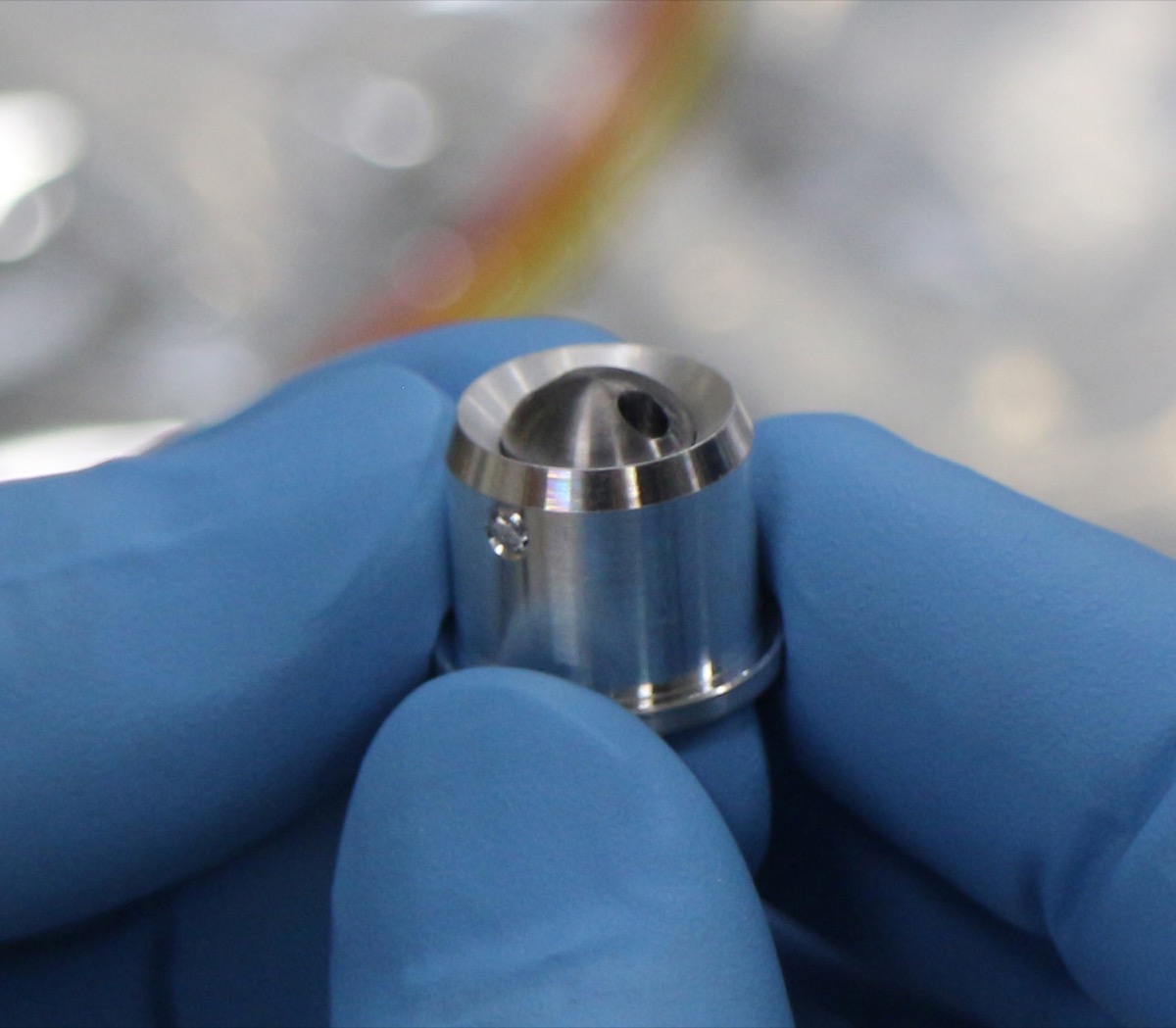

This week, Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft made contact with the asteroid Ryugu. Plans call for the lander to fire a bullet made of tantalum into the asteroid’s gravelly surface, in hopes of blasting off dust and fragments that could be collected in a sample container for a later return to Earth. Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer at Gizmodo, joins Ira to talk about the mission to Ryugu and what the team hopes to learn.

They’ll also chat about new information in the question of what led to the demise of the dinosaurs, the sequencing of the great white shark genome, and a warning from the FDA not to seek a fountain of youth in transfusions of young blood, in this week’s News Roundup.

Ryan Mandelbaum is a science writer and birder based in Brooklyn, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, coming to you today from the studios of KQED in San Francisco. Later in the hour we’ll be talking about art acne, these little dimples that are all over Georgia O’Keeffe’s famous paintings.

But first, last night, Japan’s Hayabusa 2 spacecraft made contact with the asteroid Ryugu, part of a plan to collect material from the asteroid’s gravelly surface, and eventually return it to the Earth. Ryan Mandelbaum, science writer at Gizmodo is here to talk about the mission, and other short subjects in science. Welcome back, Ryan.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Hey Ira, how you doing?

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about this mission. What’s the goal here?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah, so they want to sample material from this asteroid Ryugu and bring it back to Earth. So it’s an exciting mission. It’s really hard to land on an asteroid.

IRA FLATOW: So give us an idea of the sequence that’s going on.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Right. So just last night– so last night, right– they were orbiting this asteroid. And then they came in close. They shot a bullet made of the element tantalum at the surface hoping to kick up some of the gravel, and then capture it in a little sampling horn. If they were able to actually get any of that sample, then they’re going to fly it back to Earth and drop it off for us to go pick up.

IRA FLATOW: This has been kind of frustrating until now, right? They had a first mission that didn’t go so well?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. So this is Hayabusa 2. The first one had a couple of mishaps before dropping off a capsule with some dust in it. And then this time around they actually arrived at Ryugu. And the surface was the wrong texture. They thought that it was going to be powdery, and it was more gravelly. So they had to go back to the drawing board and test this tantalum bullet on a new mixture to see if they could still pick up some of the stuff.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. So did it look like, as you say, it did knock up some dust from the asteroid? What’s the timeline now for bringing it back?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah, so it worked in the first round of experiments. We won’t know how much they picked up until it drops off the capsule, which should be in late 2020.

IRA FLATOW: Ah, so we’ll have to wait.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: We’ve gotta wait.

IRA FLATOW: That’s exciting.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It’s exciting, yeah. It’s going to be awesome.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move back in time now. There’s news this week about what may have led to the demise of the dinosaur. You know, it wasn’t just the asteroid. The asteroid, the idea is sort of getting modified lately, isn’t it?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. Yeah, in India there’s this enormous deposit of solidified lava called the Deccan Traps. And people think that the Deccan Traps might have been formed by a 66-million-year-old volcanic eruption. A volcanic eruption that big probably would have sent gases into the atmosphere that could have partially led to the demise of the dinosaurs.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. So what’s the mechanism by which the eruption would have killed off the dinos?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Right. So it would have deposited gases like CO2 and sulfur, and then it could have disrupted the food chain– perhaps caused plants to photosynthesize less.

But the real thing here is that it’s actually two teams, one of which is detecting this huge pulse of lava right before the impact happened. And the other is detecting that maybe a quarter of the lava came out before the impact, and then most came out after. So there’s just disagreement of just how much this volcanism leading to atmospheric change might have actually contributed.

IRA FLATOW: So the timing is important, plus you also have people who are not so on board with this idea to begin with.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah, that’s right. Timing is everything here, and I think that a lot of the folks– some of the folks, at least, who I spoke to, did say, well, I’m going to think it’s the asteroid until I have absolutely concrete evidence. So it’s still going to be some more measurements until we have a yes or a no for sure. And we’ll never know.

[LAUGHING]

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s the thing. There are some scientists who love the idea. They love the chase more than actually figuring out the details.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. And something that happened 66 million years ago, I mean, we’re really piecing together a puzzle with a lot of the pieces missing.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. And there’s a story this week about shark genomes.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. I–

IRA FLATOW: Shark genomes.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah, it’s pretty cool. Well, I mean, we all love the great white sharks, right? And one thing that people– one, I guess it’s a urban legend. I don’t know where this came from. But people think that sharks are resistant to cancer. And no, that’s not true. But sharks actually do have this amazing genome that they sequence.

IRA FLATOW: Where’s Lauren?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: It’s 50% bigger than the human genome. And a lot of these genes help it heal quickly. They repair cell damage. And they seem to be genes that help prevent cells from growing out of control.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm and what else is weird about this shark’s gene?

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Well, I think that the weirdest thing here is just simply the fact that it’s A, so big, and B, just has all of these weird properties that make it so resistant to disease, and to, well, sort of to cancer, things like that.

IRA FLATOW: So we could probably make use of for people.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Well, that’s the hope. Yeah, if you study something like this long enough, maybe we’ll come up with some wild new way to cure cancer. We don’t know for sure yet, because this is just step one is sequencing the genome. But from here more research ensues, right?

IRA FLATOW: Right. And finally in other health news is the FDA has a warning for us.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. Don’t inject yourself with young blood.

[LAUGHING]

IRA FLATOW: Now, this is a thing, right? This is a thing that people do.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah, it is a thing. There is preliminary research in mice that shows that the blood of younger mice is different from the blood of older mice in that it did seem to help the health of these older mice if they injected the younger blood– if they infused the younger blood into the older mice. But that doesn’t say very much about us as people.

It hasn’t gone through rigorous clinical trials. And there’s no proven benefits yet. And so you have people who– it’s shady. People are like, well, come join my secret clinical trial, and we’ll inject young blood into you, and you’ll live forever. And everybody’s like, yeah that sounds great. But don’t do that.

IRA FLATOW: And the FDA has a warning for companies that are trying to sell this idea.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: That’s right. People are seizing on the sort of the nascent but inconclusive science right now. So they’re basically saying, don’t fall for this yet.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well. Thank you, Ryan, for keeping us up to date, and further warning.

RYAN MANDELBAUM: Yeah, of course. Thanks for having me again, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome Ryan Mandelbaum, a science writer at Gizmodo.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.