Peter A. Browne’s Hairy Obsession

17:02 minutes

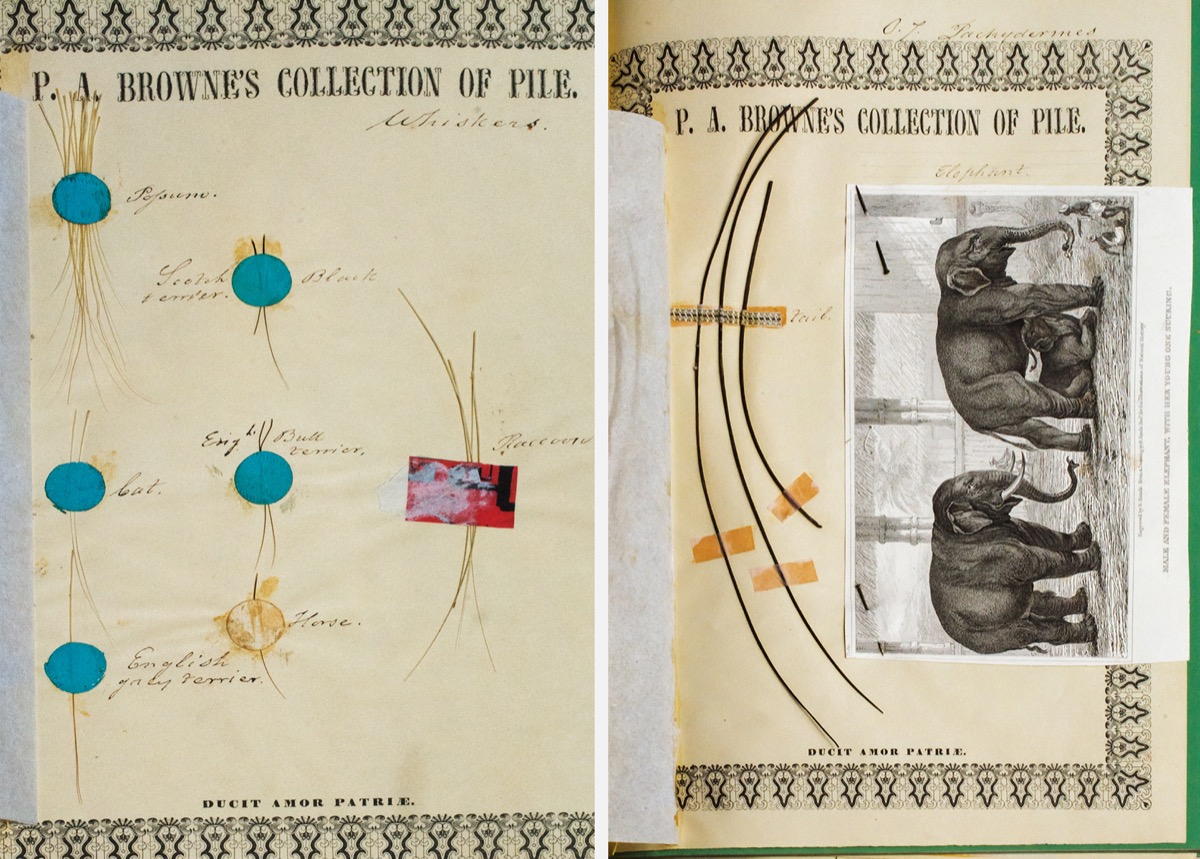

Some citizen scientists collect minerals or plants. But 19th-century lawyer Peter A. Browne collected hair—lots and lots of hair. His collection started innocently enough. Browne decided to make a scientific study of wool with the hope of jumpstarting American agriculture, but his collector’s impulse took over. By the time of his death, Browne’s hair collection had grown to include elephant chin hair, raccoon whiskers, hair from mummies, hair from humans from all around the world, hair from 13 of the first 14 U.S. presidents, and more.

Bob Peck, of Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences explains what Browne hoped to learn from all these tufts, and what his collection reveals about 19th century science.

[Millions of fossils can’t be wrong.]

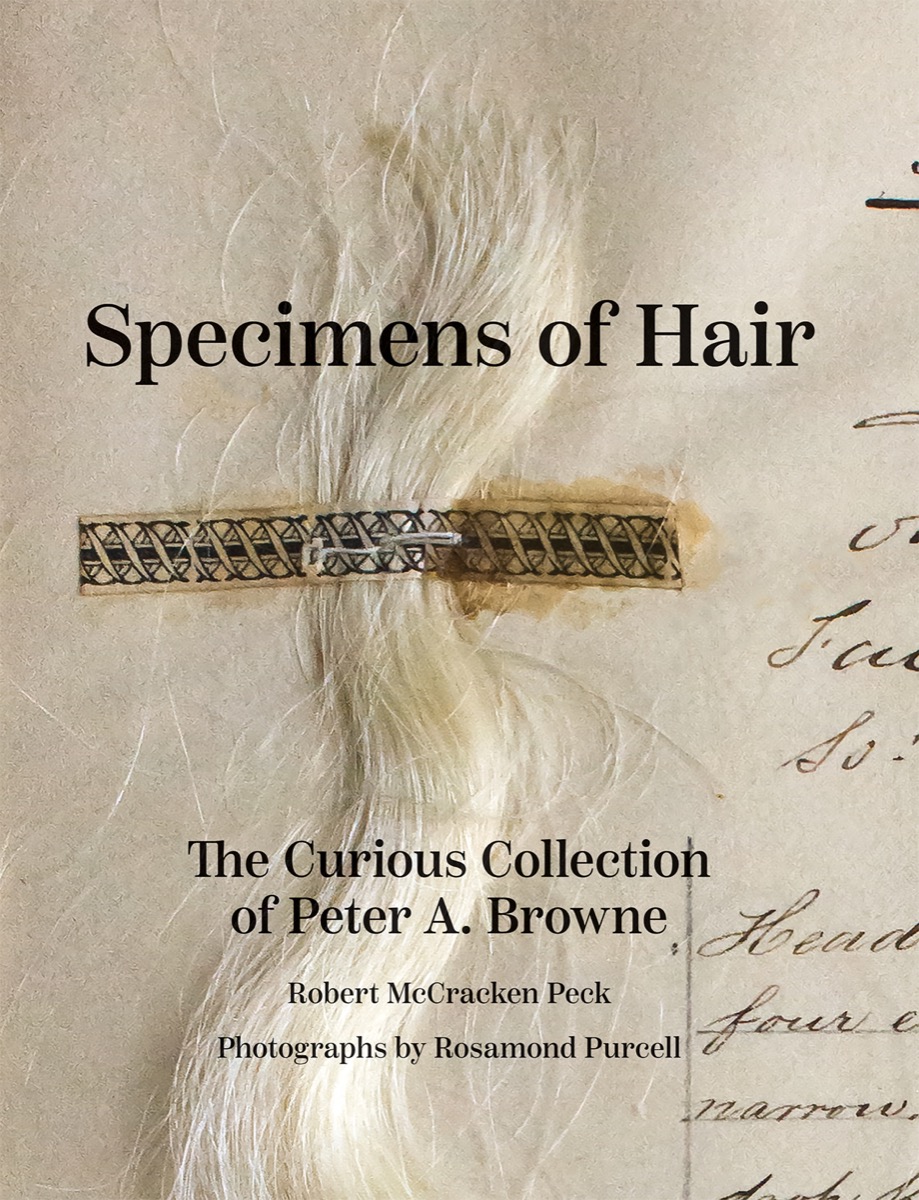

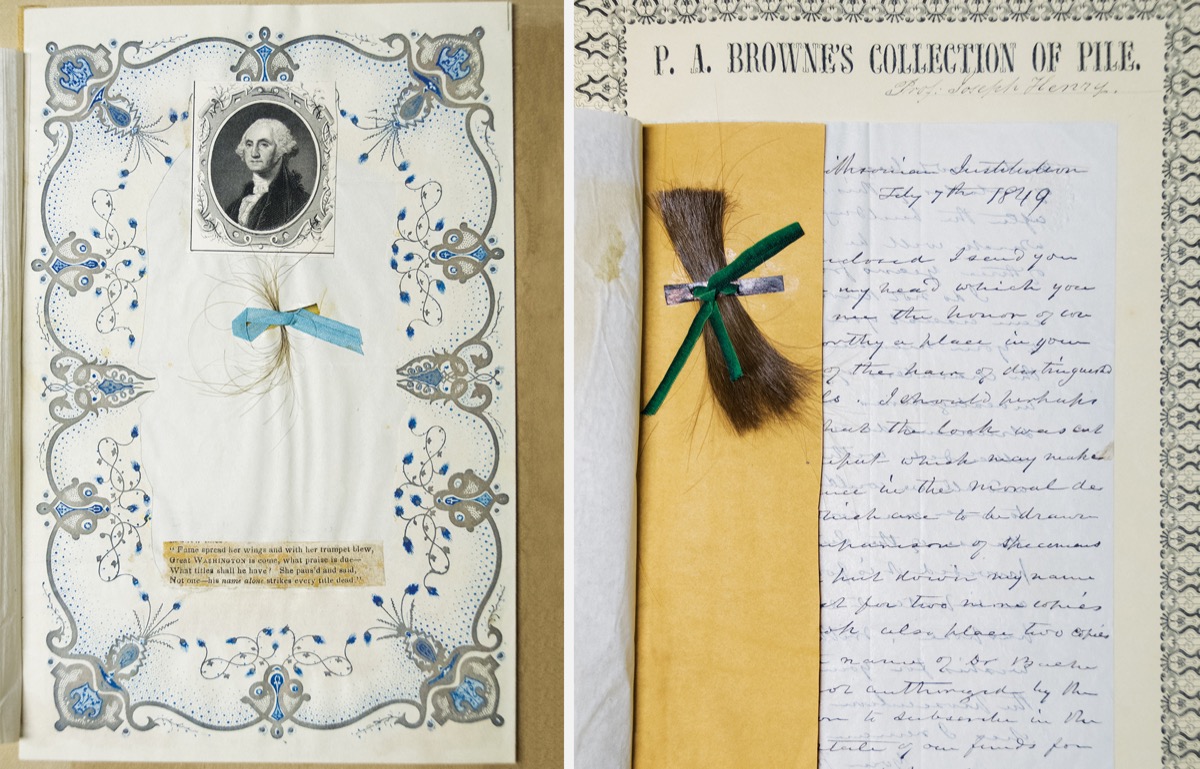

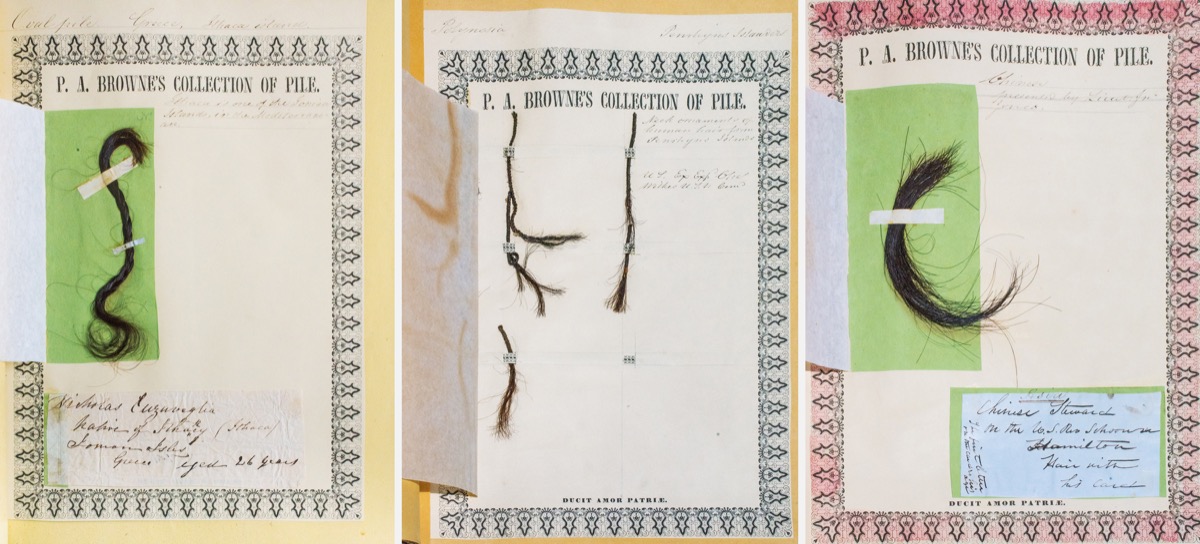

Bob Peck’s book about Browne’s collection, Specimens of Hair (Blast Books), features photographs by Rosamond Purcell of many of Browne’s prize specimens. Here are a few highlights:

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Bob Peck is the Curator of Art and Artefacts at Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky sitting in for Ira Flatow.

43 years ago, Bob Peck started a new job at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philly, the oldest natural history institution in the US. Just under a month into the job, he spotted some cool-looking metal boxes sitting in the Academy’s hallway destined for the trash. Thinking these boxes might make a cool end-table for his apartment, Bob, of course, snagged them. Only to find they weren’t empty boxes. Inside was a strange kind of collection– a collection of hair.

Inside these boxes were human hair, animal hair, hair from mummies, and hair from– get ready– from 13 US presidents. Bob had stumbled on the collection of Peter Browne, a citizen scientist whose collection of hair says as much about 19th century science as it does about the diversity of the stuff topping our heads. Today, Bob is the curator of art and artifacts at the Academy. And he’s written a book about Browne’s idiosyncratic collection. It’s called Specimens of Hair. And he joins me now to talk about it. Bob welcome to Science Friday.

BOB PECK: Thank you. Glad to be with you.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Maybe you can describe what you saw when you opened these metal boxes, some 43 years ago.

BOB PECK: Well, of course, at first I thought they were just empty boxes, since they were in the trash. But there, to my surprise, were some albums– dozens and dozens of albums, actually– beautifully leather-bound. And in each page were little tufts of hair. First few albums were sheep wool. And then we got into animal hair. And then, finally, human hair. Some of which was perfectly anonymous, but I began recognizing names on some of the other sheets that caught my attention.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I can imagine, and we’ll get to some of those names in a moment. Given what you found in there, why was the Academy throwing this stuff away?

BOB PECK: Well, we were in a process of moving from one place to another. There were lots of things that were being reviewed. And I think, the curators at the time felt that this was not something that really deserved scientific attention. They were mostly looking at the wool and some of the animal fur. And they thought, well, we’ve got full skins of animals elsewhere, why would we keep these scrapbooks, they’re just taking up a lot of space.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And they were probably wondering, what exactly can we do with hair? What does this have to do with our collection?

BOB PECK: Well, exactly. And remember, this was all in a pre-DNA era. DNA was only isolated in the 19th century, but identified in the 1950s. And then the complete human genome wasn’t sequenced until 2003. So all of this back in the 1970s was not recognized really for the value that it is today.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So this is the collection of Peter Browne. And this is a big part of the story. Who was Peter Browne?

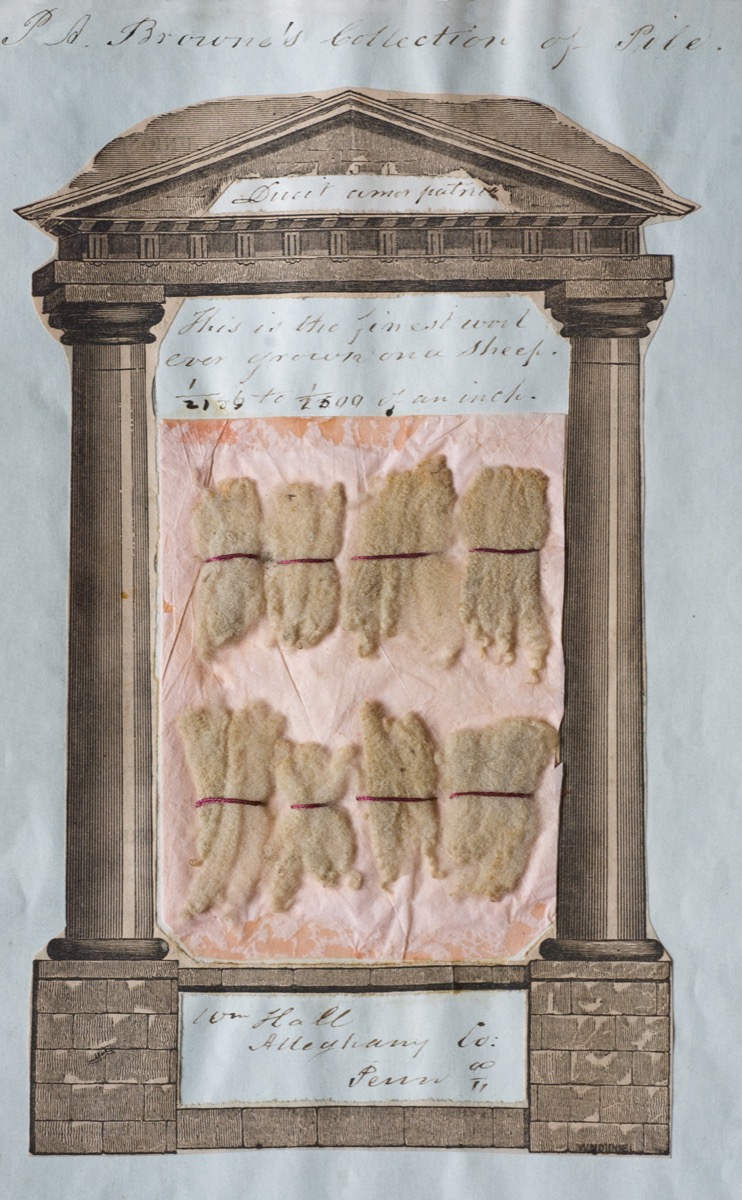

BOB PECK: Peter Browne was a lawyer in Philadelphia, but a very patriotic and philanthropic man. And he was trying at first to help advance the agricultural world in America. He was collecting sheep wool from all over the world, so that he could instruct the growers of sheep here which breeds would be best suited to which purposes. So this one might work well for a blanket or a sweater, this one might be good for a felt hat. And people hadn’t really paid much attention to that until he began to do so.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Go ahead, please continue.

BOB PECK: Then he went from one step to another. He thought, well, if we can do all this with sheep wool– and he was examining the wool very carefully. He had invented a little mechanism to test its strength and its size, called a trichometer. He was looking at it with microscope. He said, if I can study this much about sheep wool, maybe there are things in other animal wool and hair that could be useful to us.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But that’s what’s interesting–

BOB PECK: So he sent out letters asking.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I have to ask you, though– but that’s what’s so interesting about this, because it makes sense that you would find sheep wool interesting, because you can make things out of it. But elephant tail hair or raccoon whiskers– what possible use could this have to human industry?

[LAUGHTER]

BOB PECK: Well, that’s what we might say now in retrospect. But at the time, anything was possible. And in fact, some of the things he found did prove to have commercial value. And we still use cashmere, which is from goats. We use alpaca and llama fur, and various other things. In the 19th century, actually quite a bit more of it was being used. Not necessarily for blankets, but for putting in cushions and insulation. Sometimes even animal hair was used in wall plaster.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Now, when he collected all this animal hair, part of what he was trying to study was what he could learn about these different animals and how they might be related to one another. And this was all pre-Darwin. What was he learning about animals or at least thinking he was learning about animals through studying and collecting their hair?

BOB PECK: Well, I think, as you say, pre-Darwinian era, trying to figure out just what might be related to what. These great charts that we’re now used to in our science books that tell us how things are related didn’t exist then. And he was thinking that perhaps by looking under a microscope he could tell if this kind of shrew was related to that one, or a mouse, or a rabbit. Whether a giraffe was any relation to a wildebeest, and so on. And I think at that point he was just throwing the net as widely as he could to figure out what might come up out of it.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So then why does he start to collect human hair? What was he trying to learn there?

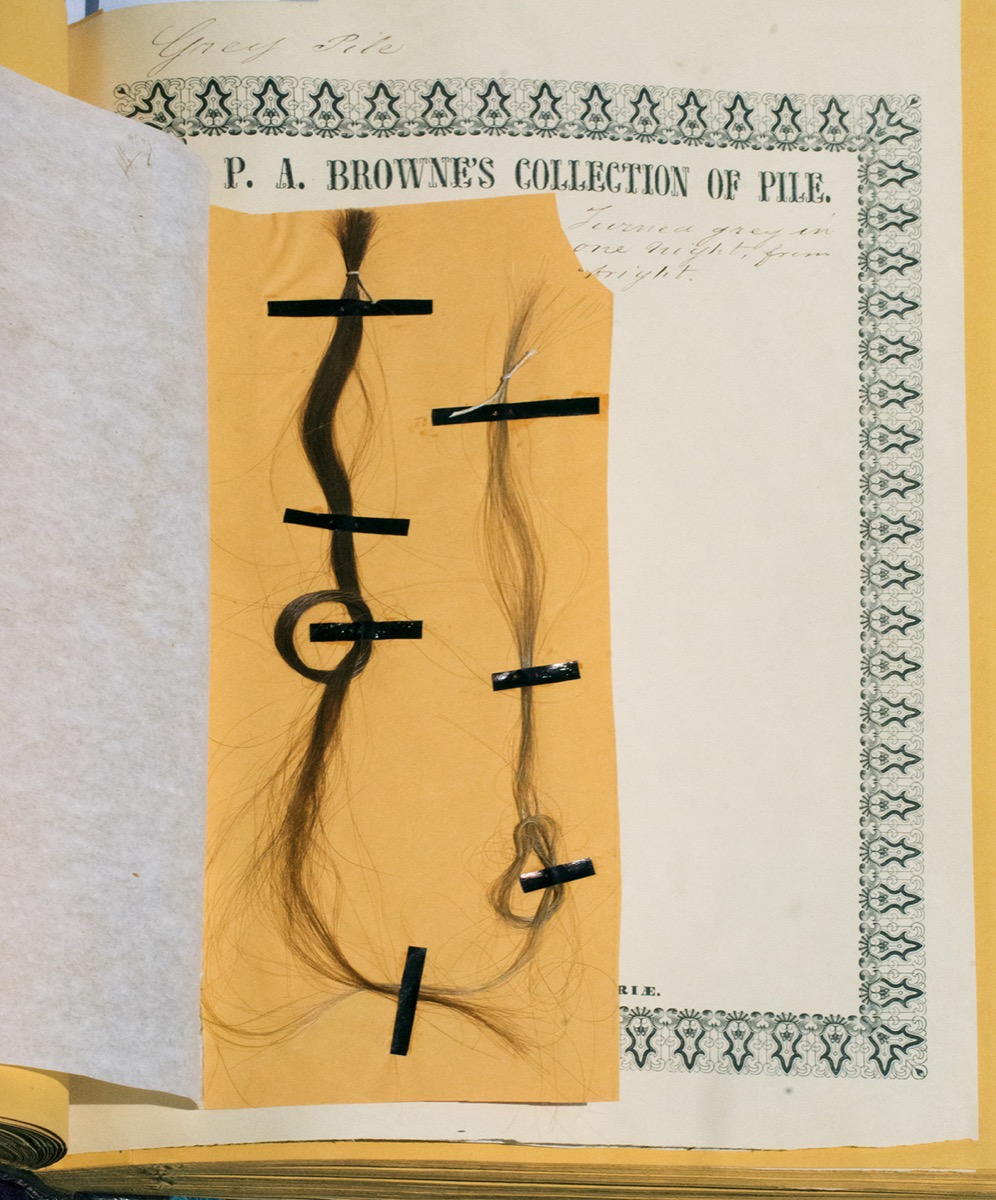

BOB PECK: And human hair– the same kind of thing. And remember, this was an era when phrenology was kind of a pseudoscience. People were thinking that the bumps in one’s skull might help tell something about their personality. He thought, well, maybe hair could tell us something, too. So he wanted the whole range of humanity. Everything from criminals to presidents of the United States, from writers, musicians, politicians, to the average person. He wanted young people, old people, and all sorts of ethnic groups.

And he put these very carefully into the albums. Each page was devoted to a single donor. A little Greek key motif around the edge, sometimes a portrait if the person was well enough known to have an engraving. And all the information that he could get about them written out carefully as sort of a label. He asked people to help him all over the world. Indian agents on the frontier, explorers who were traveling in the South Pacific and around the world, as well as his own friends and correspondents domestically.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So this is the part of the story where it turns maybe a little bit dark, because as you say, of the pseudoscience of phrenology and where science was at the time, some of the conclusions he was drawing seemed to suggest that different type of people had different type of hair, maybe even that there were different species of human. Or you could learn something about someone’s intelligence or capacity through their hair. Maybe you can talk about how he got this so very wrong at the time.

BOB PECK: Yes, well, it was a general area of discussion at the time is were people– if they appeared to be different, were they actually different? And the same was going on in other fields of science. So people would look at different birds and different colored feathers, or mammals with different fur, and thinking, well, if this one is different from this, perhaps it’s a different species.

When he looked at human hair, he divided it all into three different groups. They were either cylindrical– that is, round– which he found related to people from Asia, Central America, South America. Proving that American Indians, for example, had, in fact, come across the Bering Straits and were related to those from Asia. Second category was oval, and he found that was mostly people from Europe and England. And therefore, most of the white population in North America. And then eccentrically elliptical, which is the way he described African hair that he found.

So once he had broken these into the different classifications, then others took that information and tried to use it as proof that, in fact, there were different species of humans. We now know, of course, that that’s not true. But at the time, it was part of a general discussion.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And it really does tell us something about the state of science at the time. It’s not just this eccentric hair collector who is making these findings and trying to figure out about the human species through his discoveries. But this is the type of science that was going on at the time that he was alive.

BOB PECK: Yes, absolutely. And in every field, as I say, people were looking at insects and fish and plants, and trying to classify and organize them. And Browne was just simply part of that process. We were fortunate that he made the collections he did, not so much for his conclusions, but for the very fact that he preserved these things, because many of the people whose hair he arranged to be collected are now much more difficult to isolate genetically from a DNA point of view. But at the time he was collecting them, there were tribal groups and people living on islands in the South Pacific, and so on, who had not yet had contact with the Western world. And therefore, their hair samples are about as pure as one can get in this field.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, let’s get to the way in which he collected this human hair, because this sounds so incredibly unusual to us here. I was talking to our producer, Annie, about this. Hair kind of grosses me out. The idea of a big box of hair is not the most appealing thing in the world. And the idea that you would– I don’t know– send a letter to someone and say, hello, may I have a lock of your hair? Today, sounds so strange, but that’s actually something that was done back in the day.

BOB PECK: Yes, it was quite common in both 18th and 19th century. People, families, almost universally exchanged hair with one another. Kept hair in lockets, and brooches, and rings, and cufflinks, and so on. During the American Civil War, almost every soldier in the field would have had a locket of his wife, or his girlfriend, his mother. And at home, likewise, they would have been retaining lockets from him as he went off to war. It was a very intimate way to exchange a close relationship with someone else.

Interestingly, some celebrities were also considered fair game. And even George Washington, right in the midst of the American Revolution, received a letter at Valley Forge from a stranger saying, Dear General Washington, can I have some of your hair? And he very nicely obliged with a letter and a little snippet.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Right in the middle of Valley Forge. Things aren’t going all that well for him, but someone asks for a lock of his hair and he sends it along.

BOB PECK: He was quite flattered by it. And his wife Martha was actually sending out hair to all kinds of people, whether they asked for it or not.

[LAUGHTER]

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s like sending out a head shot today. So I have to ask you, how did he know that he actually had George Washington’s hair? I mean, he had the hair of 13 presidents all the way up to, but not including, Lincoln. How did he know that the hair he was collecting was actually the hair from those men?

BOB PECK: Well, with all of the living presidents of his time, he was able to write to them directly. And we have in these albums, their replies– the handwritten notes that they’d sent back saying, oh, I’m so sorry, I just had my hair cut, but if you wait for a month, I’ll send it. And then others– if the president was no longer living, he would write to their immediate family– daughter, granddaughter, whatnot– and say, could we have some of the hair.

And those families had all universally retained the locks of their ancestors for their own use and also with the intention of sharing them. When George Washington died, his secretary was asked to cut as much hair as he could from him before he was buried, because he knew that Martha would be besieged with requests from people who had known him during his lifetime.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m John Dankosky, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And we’re talking with Bob Peck about the fascinating book, Specimens of Hair, The Curious Collection of Peter A. Browne. You’ve kind of picked up this, as you’ve been a collector yourself, and you’ve asked former presidents for samples of their hair. What kind of responses did you get?

BOB PECK: Well, as you might guess, not much response from most of them. In fact, I’m probably in some file somewhere as someone to be avoided.

[LAUGHTER]

JOHN DANKOSKY: A no fly list. Yes, please.

BOB PECK: But I did get a very nice letter back from Jimmy Carter. I had invited him to come to Philadelphia in 2016, at the time of the Democratic Convention, to see an exhibit of the hair that we had on view. But I said, if you would like to donate some of your hair, we’d be happy to add it to the collection. And he wrote a very nice letter back saying, he wasn’t coming to Philadelphia and wouldn’t be able to see the show, but he’d be happy to donate if we really were interested. And so he did. And so he is the most recent president since Franklin Pierce to join the collection.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s amazing. Can we learn anything about the hair donors from their hair? I mean, as you say, obviously technology has come quite some way. Can we do DNA testing on George Washington’s hair and find out a little bit more about the environment where George Washington lived, or how he physically looked or was?

BOB PECK: We can very much so. And I think as technology advances in the years to come, we’ll be able to tell even more and more about this from these samples. But we can tell something about his diet and the atmosphere, and so on. Some of the studies that were made of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings and their relationship have been derived from hair samples from Jefferson and his descendants.

And recently in Europe, there was a study of Napoleon Bonaparte’s hair, because there had been concern that he might have been poisoned during his final months in St. Helena. And in fact they did find almost 100% more arsenic in the hair samples than his contemporaries.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So literally, through studying the collected hair of Napoleon, you’re able to find something about the end of his life that you just wouldn’t have known otherwise, that may have just been a story or a rumor.

BOB PECK: You can indeed. And I think as time goes on, we’ll be asking more and more questions that DNA will be able to tell us that we never could have dreamed of even a few years ago.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I have to ask you about the mummy hair. We’ve been talking a lot about people and some about animals, but where did Browne get it and why did he want mummy hair?

BOB PECK: Well, there was a very interesting guy named George Gliddon who was traveling around the US at the time. He had been our representative in Egypt. And he came to America with mummies, and went on a lecture tour with a huge diorama behind him that showed the Nile, and the pyramids, and so on. And he drew huge crowds. So 500 people or 800 people would come to hear him in a single night, and tens of thousands of people heard him over the course of a few years.

He inevitably was introduced to Peter Browne. And Peter Browne said, well, if you’re doing all this work on Egyptian mummies, could you save a little bit of the hair for me? I’m getting it from all over the world, but I also would like to have a kind of a time track on this. And we know how old some of these mummies are, perhaps that will shed some light– does hair change over time, do ethnic profiles alter and morph through the centuries? And so Gliddon very happily cooperated.

Now, Gliddon himself was a little bit of an unsavory fellow and he was sometimes stealing these things from graves and without permission taking them. But Browne, as long as he kept a certain distance from Gliddon himself, was happy to receive the specimens.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, we just have a few seconds left. Do people ask you for samples of this hair collection to test it in any way all the time?

BOB PECK: Well, we haven’t had the request yet. This hair collection has been pretty much in storage and out of sight for a while. But I think with the publication of Specimens of Hair– this new book– we’re going to be getting a lot more requests.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, it’s a fascinating book. Bob Peck is curator of art and artifacts at Drexel University’s Academy of Natural Sciences. His book about Peter Browne’s hair collection is Specimens of Hair. Thank you so much, Bob, I appreciate it.

BOB PECK: Thanks for the invitation.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And if you’re curious about what all this looks like, you can go to ScienceFriday.com/hairbook.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.