Science Put On Pause Under The Government Shutdown

22:38 minutes

The partial shutdown of the U.S. government is approaching its third week, and it has caused a backlog for scientists employed or funded by the government. Scientists have had to leave data collection and experiments in limbo. The Food and Drug Administration has had to suspend domestic food inspections of vegetables, seafood, and other foods that are at high risk for contamination.

Journalist Lauren Morello, Americas bureau chief for Nature, puts the current shutdown in context to previous government stoppages. Morello also tells us how agencies and scientists are coping during this time and what we might see if the shutdown continues. And Science Friday producer Katie Feather reports back from the American Astronomical Society conference about how the shutdown has affected the meeting and the work of scientists.

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Lauren Morello is the Americas Bureau Chief at Nature in Washington, D.C.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. As of Saturday, the government shutdown will be the longest one on record, and the shutdown is government wide. We all know that. But we wanted to focus at the details. Look at the details of how this shutdown is affecting science, because the shutdown is trickling down into places you may not have imagined.

For example, the big meeting this week of the American Astronomical Society that happened in Seattle, about 15% of the scientists and the presenters who had planned to go couldn’t. Because well, they work for the government. Our producer Katie Feather was there, and she’s here with us now to tell us how that meeting was impacted by this shutdown. Welcome, Kate.

KATIE FEATHER: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Could the scientists not go because their travel budgets were cut?

KATIE FEATHER: No, so actually the flights were already paid for, their hotel rooms were booked, people registered for this conference months ago. The reason why they couldn’t get was because federal scientists are not able to do any work while the government is shutdown, and attending this conference would be considered part of that. They’re not allowed to represent the government in any sort of official public capacity.

IRA FLATOW: Huh. That is quite a shame, because this is really a pretty big conference, isn’t it?

KATIE FEATHER: Yeah. This is the biggest conference of the year for astronomers and astrophysicists. Usually about 3,000 people attend, but this year because of the shutdown, nobody from NASA or the National Science Foundation could go. And this was a huge loss because NASA especially is one of the biggest players at this conference. Organizers said that probably close to 400 people had to cancel their plans because of the shutdown. And that’s likely a conservative estimate.

IRA FLATOW: And the conference itself had to bend some of its own rule.

KATIE FEATHER: Right. The conference organizers did the best they could, given the situation. They allowed coauthors to give presentations or talks if a lead author was unable to make it. They streamed their big plenary sessions online so people who had to cancel could still watch from home. I sat in on one talk where they had a presenter from NSF give his talk over a web conference.

It wasn’t exactly successful, but I appreciated the effort. Really, though, the that saved the conference from being torpedoed by the shut down was university scientists and NASA contractors who are not affected by the shutdown stepping in for their public sector colleagues in a really big way.

IRA FLATOW: Now I know you talk to some of the attendees there about their thoughts on the shutdown.

KATIE FEATHER: Yes, so I mentioned NASA contractors, because of how they’re funded, were still able to attend the conference. And I talked to a couple of scientists with the university’s Space Research Association, who are in charge of a space research telescope that gets flown on a Boeing 747. It usually flies three to four times a week, they said. But the plane is operated by NASA employees, so even the plane’s security guards can’t work. So the shutdown has grounded this telescope.

SPEAKER 1: There are several observations that were supposed to do in coming months that are time-critical observations.

SPEAKER 2: Yeah, we also have got comets.

SPEAKER 1: They’re fleeting observations, like comets.

SPEAKER 2: And as a time goes up, we can’t make up that time. So they just lose their science.

KATIE FEATHER: I also talked to John O’Meara, chief scientist at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, who said forget the science for a second. This is having a real human impact on my NASA colleagues.

JOHN O’MEARA: I can call them up and ask how their day is going. But I can’t call them up and even ask them to think about a science thing, because that’s work. And they’re not allowed to. And I start to worry about some of the people, especially the junior people in the field, who they pay rent. And now they don’t have money to pay for food.

IRA FLATOW: That’s something we don’t really think about when we talk about scientists, is that the shutdown seems to be having effects that we don’t think about.

KATIE FEATHER: Yeah. And another important thing, Ira, about this conference is that this is where a lot of the business of science starts. Aerospace contractors, like Ball, Lockheed Martin, Boeing, they send folks, to this conference to show off their latest engineering tech, and hopefully strike up some business with NASA. But NASA wasn’t there.

So it’s not like this is the only chance these companies have to make a government deal this year, but it’s an important networking event for them. And it’s been lost because of the shutdown.

IRA FLATOW: Great reporting, Katie. Thanks for joining us.

KATIE FEATHER: Thanks, Ira.

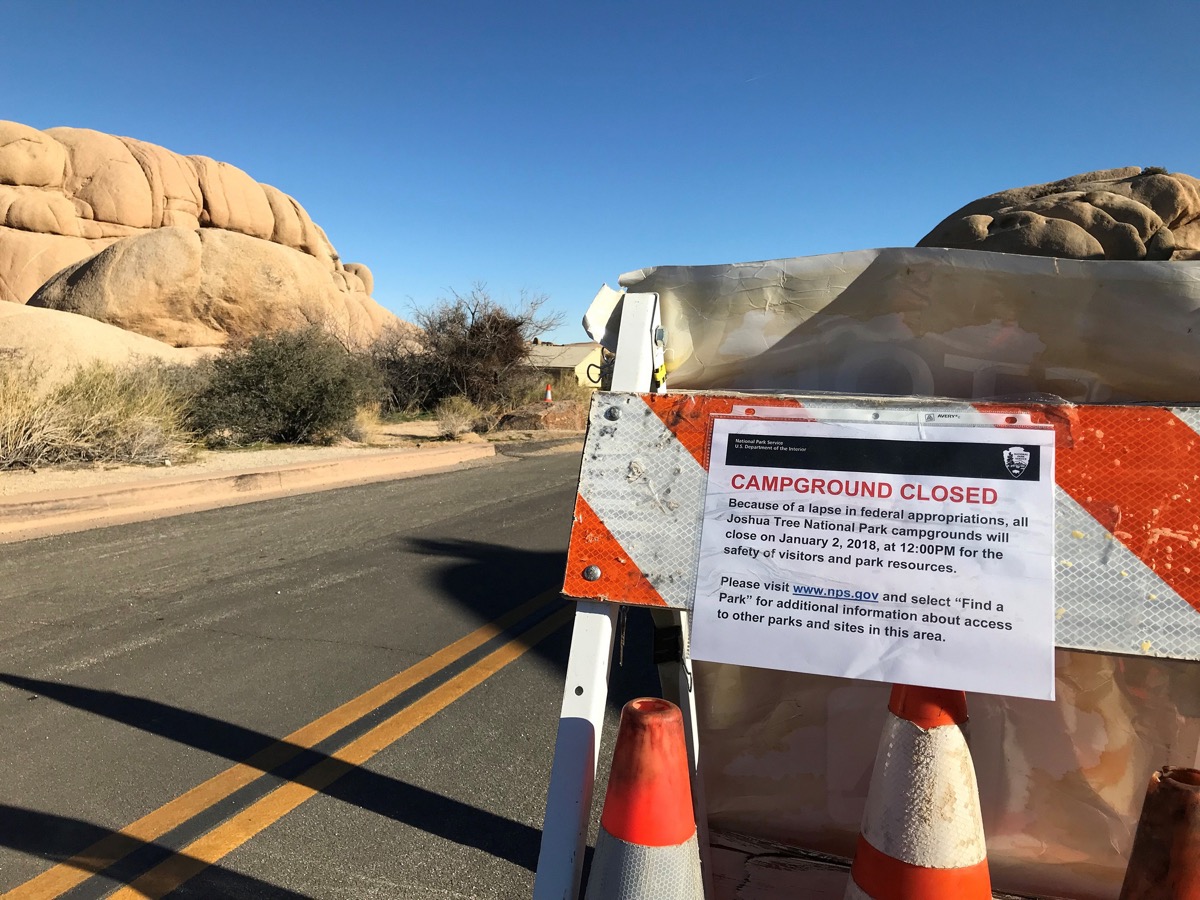

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for going there. Producer Katie Feather. You’ve heard that non-essential employees are being asked to stay at home. Parks are open, but they’re understaffed. Agencies like the FDA have cut back on food inspections. So the shutdown is also reaching into issues like health and safety, and also in ways you may not have imagined.

The devil is in the details, and my next guest has compiled the list of those details, as well, as what might happen if the shutdown continues indefinitely. Lauren Morello is the America’s bureau chief for Nature. She’s here with the details. And I want to shout out to everybody who’s listening.

If you’re a scientist or in a science related industry that has been affected by the shutdown, we want to hear from you. Our number is 844-724-8255. 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us, @scifri. Lauren, welcome to Science Friday.

LAUREN MORELLO: Hey, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Now, these shutdowns have happened, the last one that happened was in 2013. Can you put this one in context of the bigger shutdown picture?

LAUREN MORELLO: Sure. So there are two main differences between that shutdown and this one. The 2013 shutdown hit a wider array of agencies. The National Institutes of Health, which does biomedical research, and the Energy Department, which operates national labs like Los Alamos, were affected by the 2013 shutdown. This time they’ve escaped. But this shutdown has gone on for 25%, longer or a week longer than the 2013 shutdown did.

IRA FLATOW: And you hear that nonessential employees are being furloughed. And in terms of science, who is essential and who is nonessential?

LAUREN MORELLO: You know, agencies have a bit of leeway to decide that. There’s a really wonky early named government law, the Anti-Deficiency Act that lays out what happens during a shutdown. And the general guideline for who gets to be considered essential is your essential if you’re necessary to protect life, or property, or both.

And for example, at the US weather agency, NOAA, that means that about 5,000 weather forecasters are staying on the job. But at the National Science Foundation, which has a very small staff, and basically hands out grants to researchers and universities, they’re only keeping 60 of 2,000 people working during the shutdown.

IRA FLATOW: And the EPA?

LAUREN MORELLO: The EPA is an interesting one they did some interesting accounting they used what’s called no-year money, or multi-year money, these are horrible wonky names, to keep the agency going for a couple of days after everything else started shutting down. They went about six days and then they ran out of that money, and they had to wind down so there. So there are about 14,000 people at EPA who are on furlough, or enforced leave, and something like 750 who are allowed to keep working right now.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. And what’s ironic is that after two years, we finally have a science adviser, but he’s shut down too, is he not?

LAUREN MORELLO: Yeah it’s, you know, Trump has gone– President Trump has gone longer than any other first-term president since at least Eisenhower in getting a science adviser into office, and he was confirmed by the Senate last week. And when we talked to him, he said I’m talking with the White House counsel to determine whether I can go in and start work. Because I don’t know if my job is considered essential.

IRA FLATOW: And you also talk to some scientists who had to cancel their field seasons.

LAUREN MORELLO: Yeah, it’s– you know, they’re really heartbreaking stories. Just yesterday, we put out a story. There’s been a study going on for 60 years in a little island in Lake Superior in Michigan. It’s a study of predators and prey. It’s the longest-running study. Scientists have been tracking how wolves and moose on this island have been faring, and they can’t get to the island this year because the National Park Service manages it, and they’re not letting anybody on.

So these researchers are university researchers. They have $100,000 in GPS-enabled moose collars that they were going to go put on animals while they tracked them. And if this goes on much longer, they won’t be able to collect data this year, because the way they track the wolves and the moose is primarily by looking for their paw prints or hoof prints in the snow.

IRA FLATOW: And that’ll be gone. On the line, we have Lupita Montoya, who is a research associate in civil environmental at an architectural engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She has a project working with bringing new heating technology to communities in the Navajo Nation, and it has been put on hold due to the shutdown. Hi, Dr. Montoya.

LUPITA MONTOYA: Hello everybody, and thank you for having us here.

IRA FLATOW: Well, tell us how you’ve been impacted.

LUPITA MONTOYA: Well, this project that we’ve been working on for over here, about six years now, it’s been working closely with the US EPA, the Navajo EPA, and Dine College, which is one of the tribal colleges, specifically to identify appropriate heating technologies for this community. First study, which started a while back, was published already, and was an analysis where we looked at perception, culture, and technical assessment to look at what was appropriate for this community, in terms of bringing them to cleaner technologies for heating.

And our recommendation was that they needed a new technology, basically a hybrid stove that could burn both wood and coal. Such technology did not exist. And working with the US EPA, and our colleagues at the reservation, we were able to find a company in the Northeast that designed such a stove with the input from the Navajo Nation. Some of my own students were in the summers when I worked there.

And now that technology is USC-certified, and it’s been brought into the community. The people are accepting it as part of a stove exchange program that is being paid by a settlement agreement. And so that study of course, can only occur during the wintertime, when the heating season happens. So our study specifically looked at how to document the air quality and the respiratory health improvements associated with the use of this new technologies, which is a first of its kind in this country.

IRA FLATOW: So, now that’s been shut down. That

LUPITA MONTOYA: That has been shut down, I mean, in multiple ways we’ve been affected. For example, we have weekly meetings that we have held for multiple years. Now, our US EPA colleagues cannot attend those meetings. They are not allowed to work in any way. Legally, they’re prohibited from some doing that. Also, our funding, which was approved by the US EPA.

Funding paperwork arrived at the University of Colorado, notifying them the money’s coming. But it did not come. The shutdown came before the money. So now we don’t have that. I have a student who’s funded through that, and so myself, we don’t have that funding.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Dr. Montoya, I’m sorry to hear that. And we hope this is over soon for your sake, and for a lot of other people’s sake. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

LAUREN MORELLO: Thank you. I wanted to just mention one last thing, that this research has been done by minority faculty, and minority researchers, like myself members of the Society for the Announcement of Chicanos and Native Americans, directly impact communities of color. And these communities rely on our the few of us who are out there, to do our work.

IRA FLATOW: OK. I got can see that–

LUPITA MONTOYA: Yeah, it goes beyond the science. It goes into the affects in our communities as well. And a lot of people forget that scientists are people. And they help people too.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Dr. Montoya. Our number, 844-724-8255. Also talking with Lauren Morello. Boy, what a story that was, Lauren.

LAUREN MORELLO: Yeah, that was awful. I mean, there are so many stories like that that we’ve been hearing, and it’s really horrible. We talked to a computational biologist at the University of Rhode Island. So, he’s finished graduate school but doesn’t have a faculty job yet. He’s got funding from the National Science Foundation to do research.

But because NSF is shut down, he’s not being paid. NSF doesn’t consider him an employee. They consider him a contractor, , and the university that he’s at doesn’t consider him an employee. So he’s not eligible for unemployment, and his wife is working. It’s not enough to pay the bills. They’ve got a two-year-old little boy, and he told us he doesn’t know how he’s going to make his housing payments, or his car payments, or feed his son after the end of the month.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking with Lauren Morello of Nature who did a really great roundup of how this is being affected. And I asked for people to phone us and tweet in. We have lots of tweets that came in. Let me read a few of them.

Here’s one, Dear Sci-fi, the US patent and Trademark Office is operating from a rainy day fund from user fees. When the fund is depleted, it may shut down. That will take about a month, I think. A tweet from KRF says, “I work for a mid-sized company where 50% of our work is funded by multi-fed contracts. We’re all concerned, if this goes on much longer, our jobs and the health of our company will be in jeopardy. Contractors will not receive back pay. Our salary is based on Fed pay grade.”

And that’s a question to ask you, Lauren. How much of these scientists– can they get retroactive pay?

LAUREN MORELLO: So no federal employee is guaranteed retroactive pay after the government reopens. For that to happen, Congress has to specifically write that into law, pass that.

And they’ve done that in every previous shutdown, so I think people feel like that’s going to happen. But federal contractors don’t get backpay. So they’re really suffering, and contractors include, I think, people like that postdoc that I was telling you about.

And even for people who are certain that they’re going to get backpay when the shutdown is over, the problem is just that this one has gone on so long. You mentioned at the top of the show that if it goes on until tomorrow, it’ll be the longest one in US history. And it’ll be– they’re going for their second pay period without a paycheck.

IRA FLATOW: Uncharted territory. Let’s go to the phones before the birth the break to Patty in New Jersey. Hi, Patty.

PATTY: Hi. Just wanted to mention that there is a well-known X-ray crystallography beam line, so this is a very complicated piece of machinery that has to be funded. I’m not going to mention which one. They are waiting for their funding from National Institutes of Health, because they do basic biomedical research that could help with treating Alzheimer’s, not a small problem in our country.

And not only do these people not know if that beam line will ever be reactivated, and there are people coming, postdocs mentioned, people coming from all over the world to do research at that beam line. So these people don’t even know if their research will ever see the light of the day. This is a vital loss. And not only that, they’re not even worried about their back pay.

They’re actually worried about whether this beam line will ever reopen, and whether they will ever have a job. These are people doing some of the most smart things– these are some of the smartest guys on the planet. And they’re just worried about can they ever work again?

IRA FLATOW: All right. Interesting. Thank you for calling. Interesting perspective on that. There are lots of medical, clinical trials, probably, Lauren, that are not going to be happening with new medicines.

LAUREN MORELLO: Actually, in this shutdown, the biomedical research and clinical trials are doing OK so far. Because the NIH, the National Institutes of Health, is not affected by the shutdown.

IRA FLATOW: That’s good news.

LAUREN MORELLO: There’s one little part of NIH that does Superfund toxics research with EPA that shut down. But that’s it. And the FDA has been able to keep about 60% of its employees working in part because they collect user fees. When people apply to get new drugs, or medical devices approved, they have to pay a fee. And so FDA has been using that money to keep the kind of medical side of the work it does going.

IRA FLATOW: We are going to take a break and come back and talk more with Lauren Morello, and talk with you on the phone. Our number 844-724-8255. Can also tweet us @SciFri talking about how the shutdown is affecting you as a scientist, or someone who works in the science and technology industries. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about the partial government shutdown, and its effects on science. My guest is Lauren Morello, the Americas bureau chief of Nature journal. 844-724-8255. Let’s go for one last call to the phones in this segment. Let’s go to Washington University in St. Louis, Dr. Adie Wilson Poe, is that your name?

ADIE WILSON POE: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: Welcome to Science Friday.

ADIE WILSON POE: Thank you so much for having me, Ira. It’s a pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

ADIE WILSON POE: So I am a neuroscientist who studies how cannabis can alleviate the opioid overdose epidemic, and I use rodent models. So, I very routinely inject drugs like THC and morphine into animals to study how we can reduce the negative impact of opioids. I’m at a really critical transition point in my career.

I’m trying to jump from mentor trainee, like a post-doctoral junior faculty, to a full-blown, you know, assistant professor position. And I’m working on the very last experiment that I need to make that jump. Unfortunately, the last time I put in an order for THC to inject into my animals we were told that it was indefinitely back ordered, because the DEA is not there to verify that our Schedule I license to possess this drug is indeed invalid.

So although my grant, which is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, although that’s all operational, I’m still at a point where I’m going to need to sacrifice all of these animals because they’ll be too old to use by the time the DEA approves our drug order.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Sorry to hear that.

ADIE WILSON POE: Yeah, I mean it’s really unfortunate. I’ve been listening in and hearing all the talk of all the personnel impacts. And of course, all of that is extremely important. But animal welfare in this country is also extremely important. I take that very seriously. And for these animals to have no purpose is also quite tragic.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Thank you, Dr. Poe for calling in. Good luck with your work. So Lauren Morello of Nature, as this drags on, is it going to seep down even further into places?

LAUREN MORELLO: I think so, because you know, the rules and the policies that govern how science agencies and other agencies operate during a shutdown seem to kind of implicitly assume that these things are going to be short. And we’re in record territory now. We’ve talked to a number of groups that run big science facilities like NSF Telescopes, as government contractors.

And they generally get paid in like one month chunks. And so we’re coming, we’re closing in on that one month mark. And they’re talking to the folks left at NSF to see what they can do. The Smithsonian runs the Chandra X-ray Observatory for NASA, which is a spacecraft that looks at things like black holes and quasars.

And they’ve got emergency funding that they want to use to keep the spacecraft going. But they’ve got to get approval from NASA to keep using those emergency funds beyond a certain point. NASA’s got to probably say we need to keep this spacecraft going. And the reason that they might be able to justify that is the spacecraft is 20 years old, and there’s some worry that if they put it into sleep, essentially what they call safe mode, it might be really hard to wake it up.

IRA FLATOW: Right. We received a tweet from a fellow at the FDA, who asked to remain anonymous, and he said I’m a postdoc fellow at FDA. Luckily, we are not furloughed. But we are not allowed to work on our government-funded projects. This is a big deal, not only because we are not able to do our scientific work. But also because our work significantly influences the safety and efficacy of drugs.

Delays as long as several weeks cause delays in approvals, and even analysis of consumer complaints samples. Eventually, there will be an impact on the health and safety of Americans who rely on prescription drugs for their health and well-being, overall, the shutdown is risking the lives of people as it is prolonged. Lauren that–

LAUREN MORELLO: Yeah, I think actually–

IRA FLATOW: From the inside.

LAUREN MORELLO: Yeah. There’s another concern with the FDA, which is that they’ve pretty much stopped inspecting food. Like, they do dairy, and vegetables, and seafood. Meat is done by USDA, and I think they’re still going. But the FDA director, Scott Gottlieb, has been talking about trying to find a way to inspect at least the most high-risk foods starting next week, to put at least some of the FDA food inspectors back on the job. Because especially with things like seafood, like you can imagine with shellfish, it’s really not great to not have government inspectors making sure that those fish are safe to eat.

IRA FLATOW: All right. We’ve run out of time. You know, we have so many calls, so many tweets, we could go on forever. And we just hope this doesn’t go on forever, and we’re here next week talking about it. Lauren Morello, thank you very much for joining us.

LAUREN MORELLO: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: She is the America’s bureau chief for Nature.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.