The Cold Case Of The Triassic Phytosaurs

12:31 minutes

Mass extinctions are a window into past climate disasters. They give a glimpse of the chemical and atmospheric ingredients that spell out doom for the Earth’s biodiversity. Scientists have identified five big mass extinctions that have happened in the past. The end Triassic mass extinction—number four on the list—happened around 200 million years ago, when three-quarters of the Earth’s species went extinct. But the exact play-by-play is still a mystery.

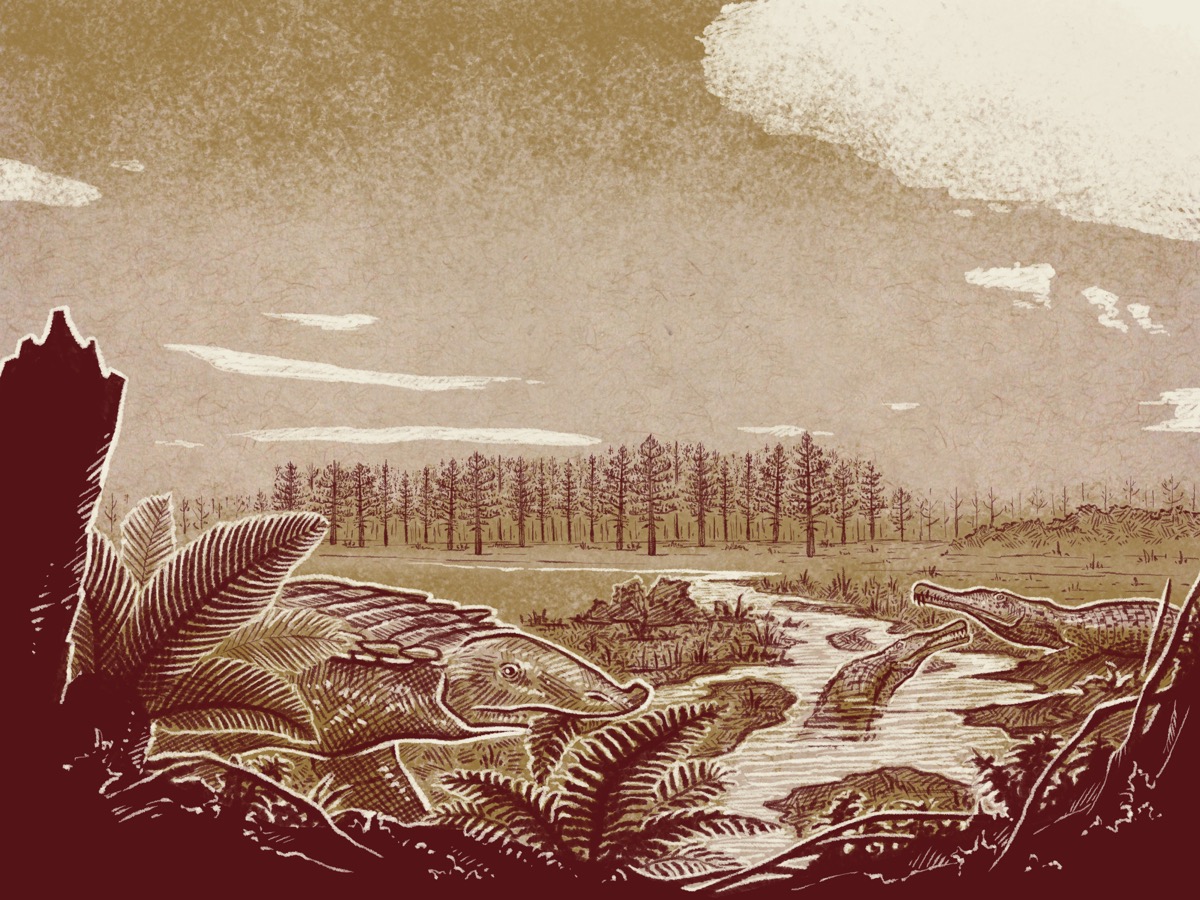

Paleontologist Randy Irmis at the Natural History Museum of Utah and his team are searching for phytosaur fossils—crocodile-like creatures that lived during the Triassic period. His teams wants to know why phytosaurs went extinct, but how dinosaurs survived and then thrived. Science Friday producer Katie Hiler and digital producer Lauren Young followed Irmis into the field, and tell us how they’re trying to piece together this climate puzzle.

Experience the trip for yourself, learn about the Big Five mass extinctions, and see what phytosaurs looked like in this piece at Methods, From Science Friday.

View a few scenes from the field below.

Have trouble remembering the “Big Five” mass extinctions? Don’t worry, we don’t blame you—Ordovician, Devonian, Permian, Triassic, and Cretaceous are a mouthful. We asked the members of the Science Friday STEM Educator Lounge to come up with some mnemonic devices to help you remember them. Here are some of our favorites.

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

IRA FLATOW: You’ve heard that there have been five mass extinctions– huge wipe-outs that have erased a whole lot of life millions of years ago. And being so far in the past, right, that makes studying these extinctions– how shall I put it? Well, quite a challenge. Paleontologist Randy Irmis and his team have been digging into the desert to piece together clues about one of those mass extinctions during the end of the Triassic. Producer Katie Hiler brings us this story from the field.

[ENGINE PULLING]

KATIE HILER: There’s nothing more annoying than having your tools break down in the middle of a job, especially when you’re standing on a Utah cliff just a few cuts away from securing one of the best fossil finds of your career.

[ENGINE PULLING]

RANDY IRMIS: The saw is backfiring.

KATIE HILER: Paleontologist Randy Irmis and his team have found a Triassic-era phytosaur skull here in Indian Creek. They’re chipping away at the rock around it, hoping not to crack the precious cargo inside.

RANDY IRMIS: We’re lucky if we find one skull a season. So if you think about a skeleton of any animal, there’s only one skull, but there’s many ribs, there’s many vertebrae, there’s two of each type of limb. So you don’t find a lot of skulls. So that’s always really exciting.

KATIE HILER: Back in the heyday of the Triassic period, 250 million years ago, phytosaurs were one of the top predators of southeastern Utah. They looked kind of like crocodiles, with long, narrow snouts studded with teeth. They even ate dinosaurs when they got the chance, though in Triassic Utah, dinosaurs were just small dog-sized meat eaters, side players, not the big Hollywood versions we think of today. But the fearsome phytosaurs weren’t built to last.

RANDY IRMIS: They went extinct at the end of the Triassic during this big mass extinction called the end Triassic mass extinction. They were super successful for 30 million years, and then they died out.

KATIE HILER: Mass extinctions are a window on past climate disasters, a glimpse of the chemical and atmospheric ingredients that spell doom for the planet’s biodiversity. You already know about the one that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. That was the fifth of the so-called big five mass extinctions that devastated the Earth. The end Triassic mass extinction, number four on that list, happened around 200 million years ago, when 3/4 of all species on Earth went extinct.

Randy’s phytosaurs didn’t make it out alive. But somehow, those small early dinosaurs did. No one knows exactly why.

STERLING NESBITT: I always think of it as kind of a black box. You have happy Triassic faunas with a few dinosaurs in there, then big question mark, and then lots of dinosaurs without all the classic Triassic reptiles.

KATIE HILER: Sterling Nesbitt is a paleontologist at Virginia Tech. He says dinosaurs didn’t just make it through the mass extinction, they thrived afterwards. And therein lies the mystery.

STERLING NESBITT: What makes a dinosaur? How are dinosaurs unique? We know they’re survivors. But is there actually something unique about dinosaurs that allowed them to take over the world?

KATIE HILER: To find out, it helps to go back to the beginning of the Triassic, to piece together a climate disaster that would decimate the Earth’s biodiversity and pave way for the dominion of the dinos. Back then, the seven continents were still united as one huge supercontinent, Pangea. But then, Pangaea began to violently break apart along the mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the Atlantic Ocean is today.

CELINA SUAREZ: So there was a whole lot of volcanic eruptions, CO2 is being emitted, methane was being emitted. And so you had global warming at that time period and big habitat changes happening.

KATIE HILER: Celina Suarez studies Earth’s early climate, and she says traces of that ancient atmosphere are trapped in rocks, like a geologic fingerprint, in the form of calcium carbonate. And those fingerprints reveal that temperatures increased between three and six degrees Celsius over the course of the end Triassic. If those rising temperatures contributed to the death of the phytosaurs, Randy would find fewer bones as he traveled through the late Triassic, and fewer species of phytosaurs, too.

But if climate change killed the phytosaurs and a lot of other species, why not the dinosaurs? Paleontologists aren’t in agreement about this, but it could have been that dinosaurs were better equipped to deal with the heat.

CELINA SUAREZ: One of the things that dinosaurs probably had going for them is that they were, to a certain extent, thermoregulating. And there’s some debate as to whether or not they were like warm-blooded like mammals are today. But dinosaurs most likely did regulate their temperature. And so that may have been one of the things that allowed them to thrive in these abandoned ecosystems.

KATIE HILER: The climate events of the late Triassic should feel pretty familiar– an increase in methane and carbon dioxide emission, global warming, ocean acidification. Celina says she is very aware of the parallel.

CELINA SUAREZ: We are always concerned about what’s going to happen in the future with modern rapid climate change. Well, that experiment has already been run in the past. So we just have to go back into the past and look at it, and evaluate it, and understand it.

KATIE HILER: Another parallel? Disappearing species. The causes and the players may be different, but the outcome could be the same. Some paleontologists have even started to call our current diversity crisis the sixth mass extinction.

SPENCER LUCAS: I think it’s fair to call it a sixth mass extinction. It hasn’t played itself out.

KATIE HILER: Spencer Lucas is a paleontologist at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History. He’s known in the field for being skeptical that the Big Five extinctions were the blockbuster wipe-outs they’re made out to be. Even so, he’s not shy about putting a label on the climate change we see today.

SPENCER LUCAS: What’s scary about it, to me, is it’s happening really fast. This is an extinction that’s only happening so far on the scale of perhaps a few hundred years or less.

KATIE HILER: Celina, on the other hand, isn’t willing to go that far, yet.

CELINA SUAREZ: Our time frame for defining mass extinction is on the order of thousands of years. So we have to be careful. However, the geology part of me that understands the long-term carbon cycle sees this as a major, major event. If you check back with me in 100,000 years, or a million years, I’d say probably, we’ll see this as a mass extinction.

KATIE HILER: So who will be the winners and the losers of this mass extinction, if indeed, we are going through one right now? The phytosaurs are gone, so are all the non-avian dinosaurs.

SPEAKER: Oh, how are you doing?

CELINA SUAREZ: Hi, everyone.

SPEAKER: We’re all a lot cleaner than last time we saw each other.

RANDY IRMIS: So, all right, are we ready to go? All right, well, welcome to our geology collections room.

KATIE HILER: Back in his lab at the Natural History Museum of Utah, Randy is examining the skull of one of the casualties of the end Triassic extinction– one of his phytosaurs.

RANDY IRMIS: And then, we can see right here, there’s two openings– the nostrils. And these are really critical because that’s one of the things that tells us that this animal is not related to crocodiles, even though it looks very similar.

KATIE HILER: There’s one more thing that sets the phytosaurs apart from the early crocs. The ancestors of today’s crocodiles made it out of the Triassic alive. Then, over 100 million years later, when all the dinosaurs disappeared from the land, it was again the mighty protocrocodiles– the ultimate survivors– who stuck it out.

RANDY IRMIS: There’s been a lot of debate about why it is crocodiles and alligators made it through living on land, whereas dinosaurs didn’t.

KATIE HILER: So I know people like to say that cephalopods, or maybe robots, will be the winners in a world altered by human-caused climate change. But if the past is any guide, I’m putting my money on the crocodiles. For Science Friday, I’m Katie Hiler.

IRA FLATOW: Great story. Katie Hiler is here to tell us more about that, along with digital producer, Lauren Young, who was also out on that trip. Welcome to the program.

LAUREN YOUNG: Hey, Ira.

KATIE HILER: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You still online putting your money on the crocodile?

KATIE HILER: I am. You know, the phytosaurs and the non-avian dinosaurs were both taken out by two different mass extinctions. But the crocodile ancestors, they held on through both of those. So they really know how to weather a climate crisis.

IRA FLATOW: That’s true. Lauren, this story is part of a sci-fi project called Methods. Tell us about Methods.

LAUREN YOUNG: Sure. We’re really excited about it. So, Methods is a project where we want to bring you into the field, but through the page. There’s an entire online piece that I wrote that goes along with Katie’s story. It takes you on the front lines of science and into the desert with Randy. So you can see videos of those paleontologists wielding that rock saw that you just heard, as well as illustrations of those prehistoric animals, hear more sounds. And we’ve got a handy interactive extinction timeline too, that if you have trouble remembering the big mass extinctions, it’ll help you out. It really all brings the story to life in a visual, beautiful way. So check it out on sciencefriday.com/methods.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk more about this story. The scientists you talked to said that climate change today looks similar to what was happening at the end of the Triassic during this big extinction, right?

KATIE HILER: Right. So, to be clear, the planet was a lot hotter back in the Triassic, about 140 degrees Fahrenheit. So it wouldn’t feel like it does today. But what’s similar is the way the climate is changing. CO2 is getting pumped into the atmosphere, causing all these different climate effects. Back then, it was volcanoes. Today, it’s humans. But the magnitude of the change is also similar. The earth was warming by 3 to 6 degrees Celsius at the end of the Triassic.

Today, scientists say if we don’t do anything about our current climate change, the Earth could warm by 3 degrees by the end of this century.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, Talking with Katie Hiler and Lauren Young– that’s pretty scary.

KATIE HILER: Yeah, it is. Yeah, we don’t want that to happen.

IRA FLATOW: So how do these phytosaurs help tell us about this climate story? Did they really suddenly drop out of the fossil record completely?

KATIE HILER: Yeah. What you see is phytosaurs all the way up to what’s known as the Triassic/Jurassic boundary. And then suddenly, once you get into the Jurassic, they’re gone. We know that they were the victims of this mass extinction caused by climate change, but we don’t have many details about how that happened. That’s why it’s this black box.

So what Randy is doing is digging up phytosaurs closer and closer to that extinction level to try and figure out what happened. Each skull he gets is sort of like a data point.

LAUREN YOUNG: Right. And so, Randy has actually found three Triassic phytosaur skulls in Indian Creek so far. So he needs to obviously search for a few more to fill out those data points. But if climate change causes extinction, Randy will see fewer individual phytosaurs, as well as fewer species as he travels further through the late Triassic rock. So that would mean there was a plunge in diversity caused by the climate stressing amounts, what they would see.

IRA FLATOW: Like Sherlock Holmes, yeah. Tell me about camping out. You both camped out overnight with Randy and his crew for this story. What’s it like to be on a dig with a paleontologist, Katie?

KATIE HILER: Ira, fossil hunting is no joke. There’s so much physical labor involved in this work. You’re hiking long distances in the hot desert. You’re lugging multiple gallons of water, so you don’t get dehydrated. There’s bags of plaster. There’s a rock saw. Randy is going to get mad at us for telling this story, but on our second day, he was working on another fossil buried in a large chunk of rock. But before he could recover that fossil from the rock, the saw broke again. So Randy just had to strap the huge rock with the fossil in it to his back. And he carries it out of the desert like that.

We were all convinced he was going to kill himself. But later on, I asked him, I was like, why do you go to such great lengths for this? And he’s like, you know, this is our data. And if we don’t have data, then we can’t do our work. I was really impressed.

LAUREN YOUNG: Yeah. I, like, completely have a new appreciation for paleontology. Like, spotting fossils in the field for the untrained eye, like me, it is so hard to do. One of the paleontologists, Andrew Milner, had asked us if we could see like a fossil that was in the site. It was a literally in a rock like right next to our feet. And I had no idea. But the paleontologists and the volunteers, they know how to read that colorful rock out there.

I couldn’t do it, but you know, they can see these, like, little pieces of bone and it could be a phytosaur skull.

IRA FLATOW: That’s why they do what they do, and you guys do what you do so very well. And I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us. This is a great series. Katie Hiler is a sci-fi radio producer. Lauren Young is one of our digital producers. And you can find the full package at sciencefriday.com/methods. Great work.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.