Welcome To The Bone Room

Biologist and functional morphologist Steve Huskey has nothing to hide, despite the hundreds of skeletons in his closet.

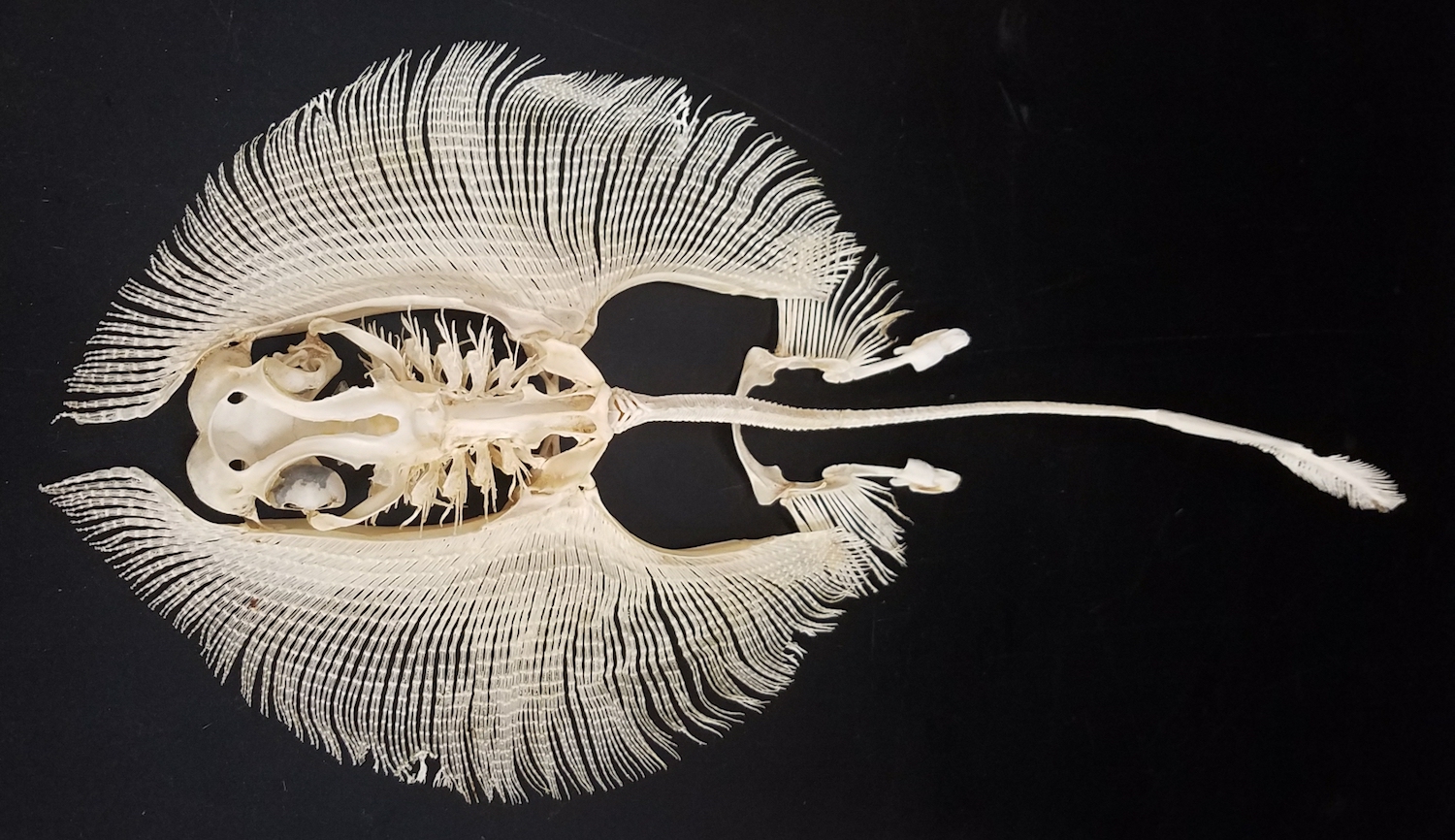

This 16-inch-long yellow stingray (Urobatis jamaicensis) would lie flat on the ocean floor, blending in with the sand. But be careful—you wouldn't want to step on one. Credit: Steve Huskey

Even before its death, this yellow stingray was like a ghost. The ocean dweller haunting the waters of North Carolina down to Florida and the Bahamas and Caribbean, would glide across the seafloor or vanish into the sand with its mottled tan skin—sneaking up on nearby prey.

But its disappearing act also works on humans. When a swimmer wading in shallow waters accidentally steps on a hidden yellow stingray, the creature defensively swings a venomous barb, or spine, on the top of its tail and stings the leg. It’s an intricate movement—one that Steve Huskey goes all the way to the bone to understand.

“Only by digesting the animals down to their cartilaginous skeleton could we see exactly what was going on in this tail to allow this spine to stab into stuff,” says Huskey, a biologist and associate professor of functional morphology at Western Kentucky University. Huskey and his team found that not only does the tail get skinnier, but the cartilaginous bands the creature uses for swimming become gapped near the barb, giving the stingray’s tail the flexibility for a painful (but rarely lethal) stab.

“It’s hard to fold steel, but if you put some perforations in it, now all of a sudden you can bend it at that spot no problem,” Huskey says. “That’s exactly what this tail is like. It’s real stiff, until those perforations are added, then it gets real flexible…. We couldn’t see that until we got down to the cartilage.”

The yellow stingray is just one of the many skeletons in Huskey’s closet—literally. In fact, you might call him an animal undertaker.

Huskey collects and constructs the remains of these deceased animals to get a closer look at how certain skeletal structures allow actions and movement—as well as preparing specimens for their final resting place in museums, aquariums, and research labs. His lab has a few hundred skeletons at any given time—from alligators to rattlesnakes to piranhas to armadillos—and thousands of photos of past specimens. There’s a lot of information that can be learned from the exterior of the animal, Huskey says, but sometimes bones can tell deeper stories about what an animal can do. And the stories Huskey is often interested in tend to lean on the fatal.

“How do venom delivery systems work? How do spines work and all kinds of stuff that’s either used for killing or trying to keep from getting killed?” says Huskey.

Preparing a skeleton takes Huskey, on average, weeks to complete. After he receives what he calls “dead goodies”—often mailed in styrofoam containers from places like zoos, aquariums, and pet stores—he thaws, skins or descales, and guts the specimen. But the real credit goes to the tiny “unsung heroes” of the process: Dermestes maculatus, a species of flesh-eating beetles.

It may sound odd to use flesh-eating beetles, but other processes that reduce animals to the bone, such as boiling and maceration, often involve submerging the specimen in water or an aqueous solution. This can make it difficult for structure to dry and stay together, Huskey explains. “The beetles are the least destructive, and I would also argue the most efficient,” Huskey says, who was in the middle of preparing a spectacled cobra to be “cobra jerky” for the beetles when he spoke to SciFri over the phone. “Nothing gets missed. If it’s edible, they eat it.”

Don’t worry, they’d rather eat flesh that’s already dead and dried.

Huskey will remove some of the flesh to ensure his colony of beetles will all get to the bone around the same time, so they don’t gnaw at the skeleton. Then, he carefully positions and dries the carcass in a pose before placing it in the plastic box of beetles—letting the hundreds of thousands of ravenous insects devour the remaining meat. If the lab is quiet enough, you can even hear the sound of the thousands of tiny mouths at work.

“It literally sounds exactly like a giant bowl of Rice Krispies with milk poured on it,” Huskey describes. “Just snap, crackle, pop.”

When the beetles finish their meal, what is left is barren bone.

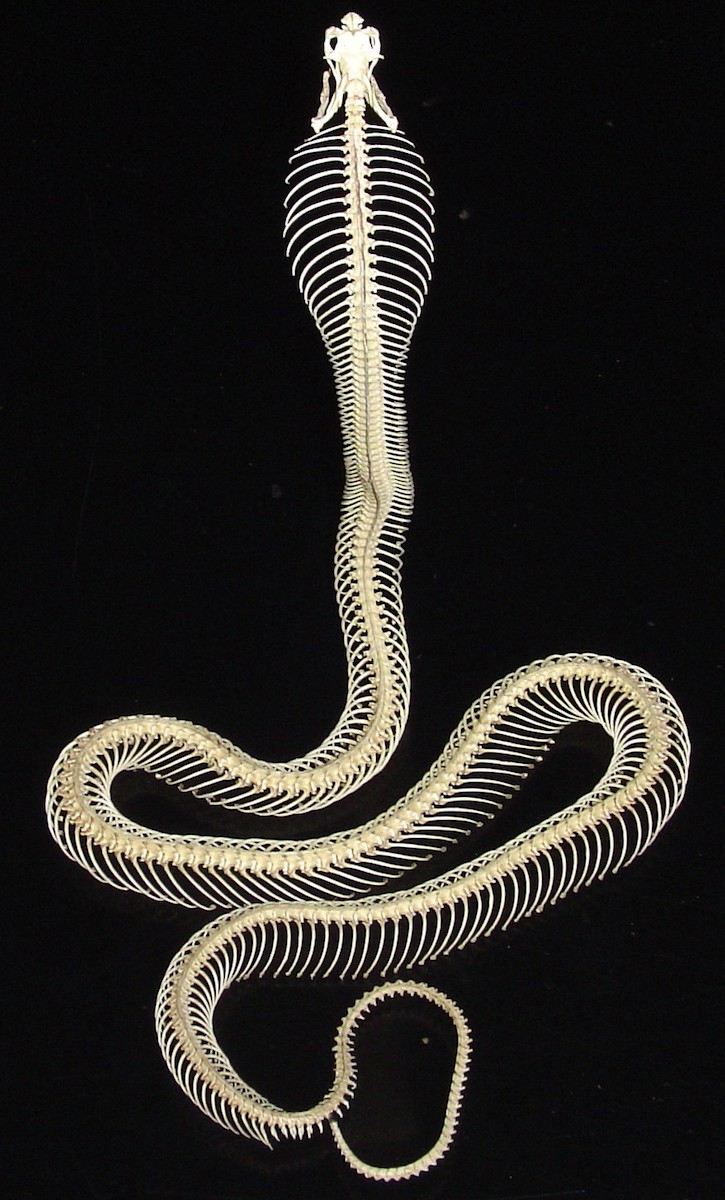

While no longer breathing, Huskey brings some life back into the dead. He arranges the skeletons to set as if they are about to bite, leap, crawl, or fly. “If I show you one of my cobra skeletons, anybody that knows a cobra will see [the prepared] animal standing two feet tall with a flared hood and go that’s got to be a cobra skeleton, so it helps with the recognition,” Huskey says. “And from my perspective and hopefully my students, if the bones are in a proper lifelike position, it gives you a better appreciation for the mechanism involved.”

The result: Creatures forever immortalized as ghosts of their former selves.

“It can be breathtaking,” he says. “When you couple the image with the sound and the smell it’s not for the weak of heart. But, having said that, almost everybody walks in there and goes, ‘this is freaking disgusting,’ and within five minutes they’re also saying, ‘but this is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen.’”

Explore more from Huskey’s bone room below.

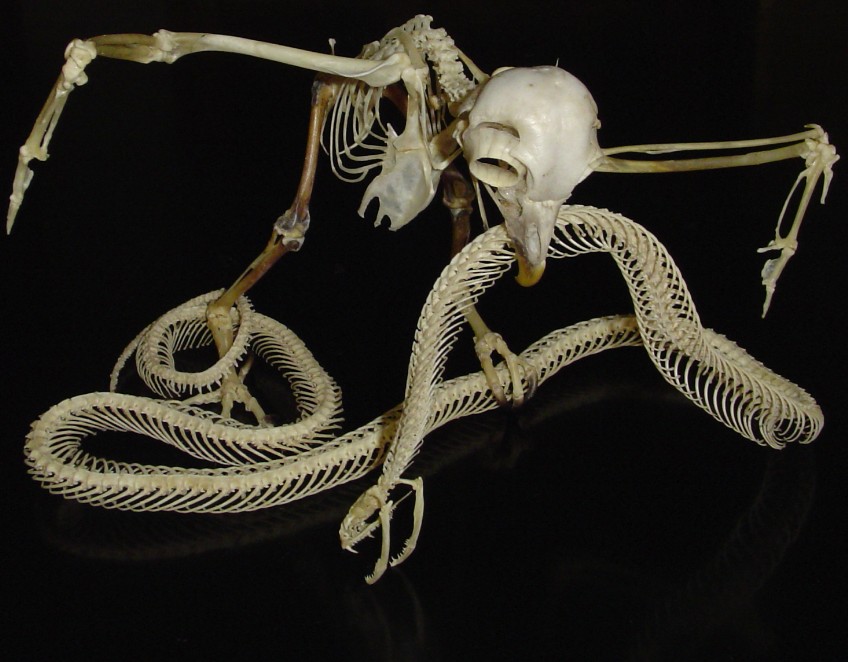

The remnants of an owl and cobra are frozen in the middle of a battle. Credit: Steve Huskey

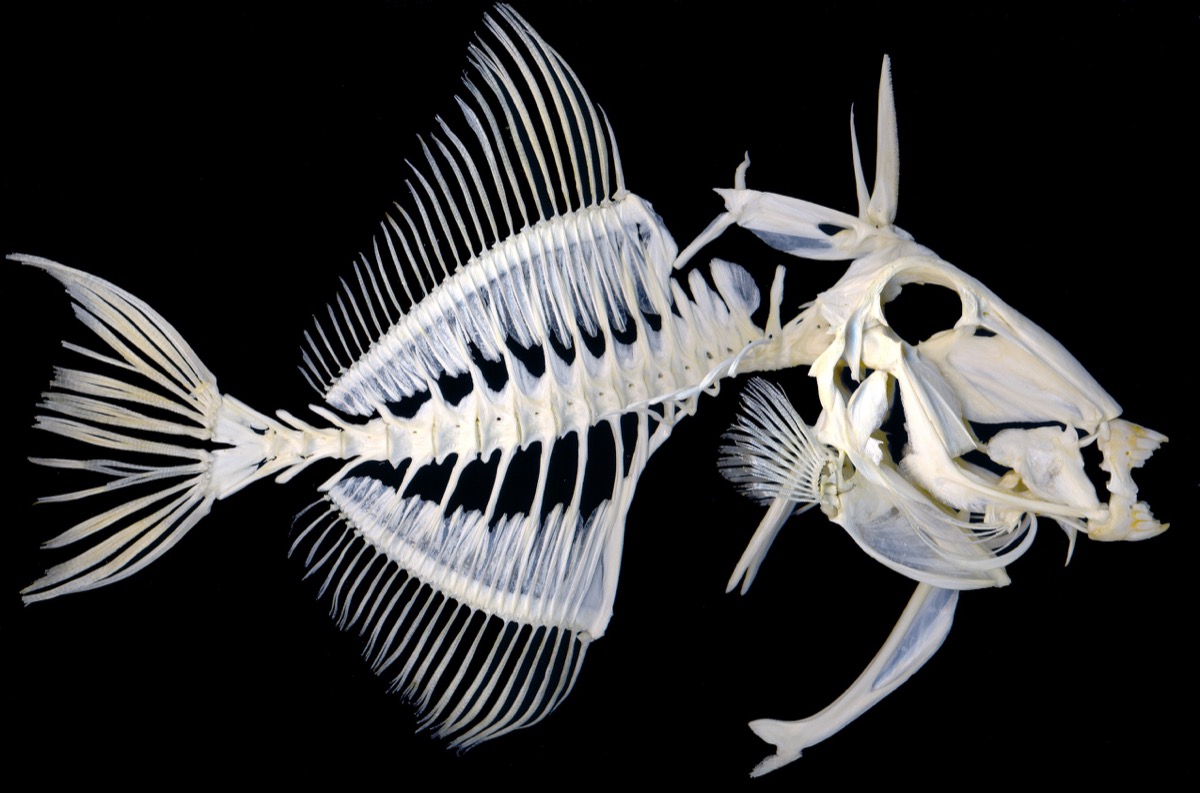

While he finds it difficult to pick one, the animal that most fascinates Huskey is the triggerfish, named after their protective spines on their backs. “Mechanistically, they have some the strongest bites pound per pound in the oceans,” he says. “And behaviorally, the biggest ones are about the size of your computer monitor, but they think they're absolute monsters. They get protective over a reef, and they are recognized now for biting ears on divers.” Credit: Steve Huskey

This is what it looks like in nature when an Eastern diamondback snake digests a squirrel, explains Huskey. Credit: Steve Huskey.

Huskey collaborated with National Geographic to study the bite force of piranhas in the Amazon, and how their jaws contribute to their incredible feeding behavior. Credit: Steve Huskey

In this scene, Huskey positions an otter and a cottonmouth snake. Credit: Steve Huskey

Barracuda. Credit: Steve Huskey

In a 2013 study, Huskey and his team looked at the skeleton of an Eastern mole to better understand how these animals create the digging force with their the limbs. “Without the skeleton we have no way of determining how their enormous muscles translate digging forces to the earth as they burrow,” he says. Credit: Steve Huskey

Veiled chameleon. Credit: Steve Huskey

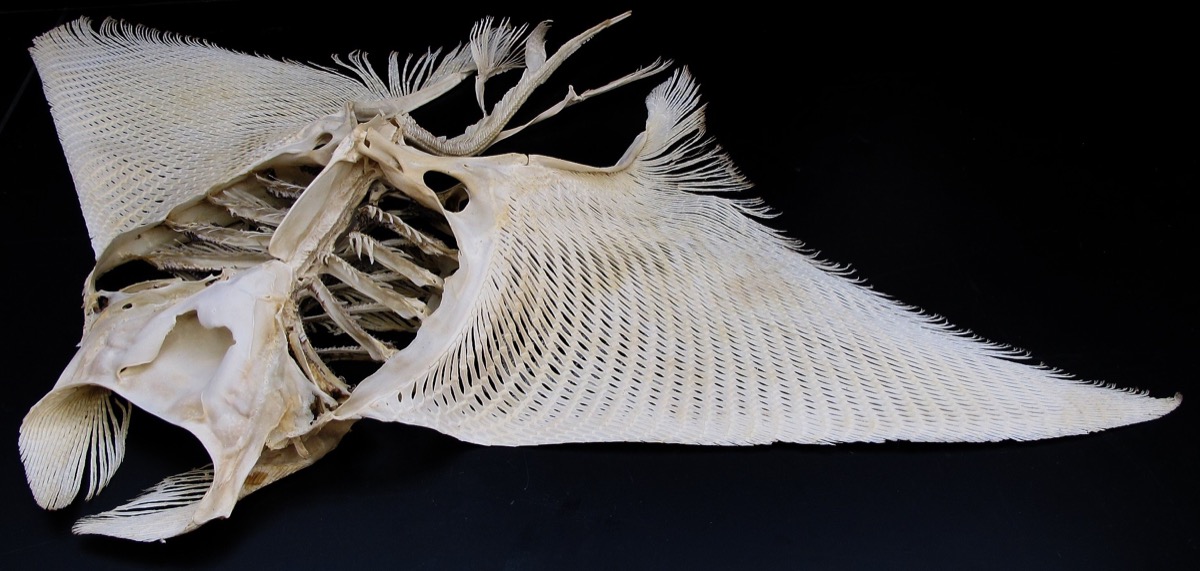

Lesser devil ray (Mobula hypostoma). Credit: Steve Huskey

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.