Read ‘A Brief History of Time’ With The SciFri Book Club!

16:49 minutes

This story is part of our summer Book Club conversation about Stephen Hawking’s 1988 book ‘A Brief History of Time.’ Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or call our special voicemail at 567-243-2456.

This story is part of our summer Book Club conversation about Stephen Hawking’s 1988 book ‘A Brief History of Time.’ Want to participate? Sign up for our newsletter or call our special voicemail at 567-243-2456.

Calling all time travelers!

Calling all time travelers!We hope you’ll join us at a Time Traveler Cocktail Party on August 21 in NYC! The Science Friday Book Club invites you to an interactive evening of games, cocktails, and activities that will expand your conception of time, space, and reality. Learn more and buy tickets here.

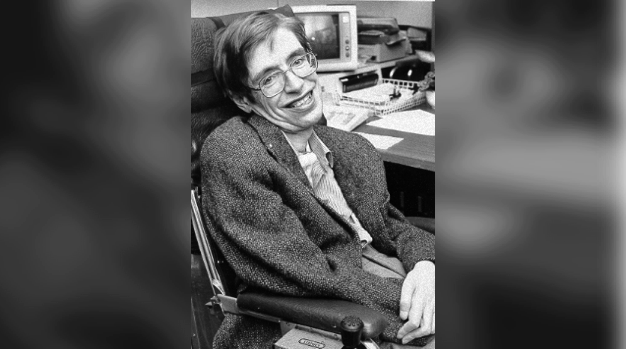

In 1988, physicist Stephen Hawking’s wildly popular A Brief History of Time introduced general audience readers around the world to scientists’ questions about the Big Bang, black holes, and relativity. Many of those questions remain unanswered, though the science has advanced in the 30 years since the book was first published. Hawking, who passed away this spring, was known not just for this book, but for his enthusiastic and persistent communication with the public about science. And this summer, the Science Friday Book Club celebrates his legacy on the page, and off.

Join Ira and the team at Science Friday as we read A Brief History of Time and ponder the deep questions about matter, space, and time. We’ll read the book and discuss until late August. And we want to hear from you! Read how you can participate below. (Your comments may be read or played on the air.)

If you’d like to brush up on your physics while you wait for your copy of the book, check out these classic SciFri segments and other resources:

Questions about the Club? Post ‘em in the comments below or email bookclub@sciencefriday.com. Happy reading!

Priyamvada Natarajan is a theoretical astrophysicist and author of Mapping the Heavens: The Radical Scientific Ideas The Reveal The Cosmos (Yale University Press, 2016). She’s a professor in the departments of physics and astronomy at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Clifford Johnson is author of The Dialogues: Conversations about the Nature of the Universe (2017, The MIT Press), a professor of Physics, and Co-Director of the Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, California.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. This spring, physicist Stephen Hawking passed away. And of course, he’s remembered for many things, including his poetic descriptions of the often technical work of physicists and other scientists. Here he is on Science Friday back in 2013, when I asked him if he thought there were any questions we might never answer.

STEPHEN HAWKING: I believe there are no questions that science can’t answer about the physical universe. Although we don’t yet have a full understanding of the laws of nature, I think we will eventually find a complete unified theory. Some people would claim that things like love, joy, and beauty belong to a different category from science and can’t be described in scientific terms. But I think they can all be explained by the theory of evolution.

IRA FLATOW: That was Stephen Hawking back on Science Friday in 2013. And in his honor, what better book for your summertime reading list than A Brief History of Time, Hawking’s groundbreaking work of cosmological communication? It is our choice for our book club. Science Friday producer and book nerd in chief Christie Taylor is here to tell you more and explain how you can participate, plus introduce you to our guests. Welcome, Christie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Hey there, Ira. So to get you excited about A Brief History of Time, this is actually something our readers from our last book club, which you may remember was Frankenstein– our readers from that last book club weighed in on what they thought we should read next. And it was A Brief History of Time, to celebrate the life of Stephen Hawking.

But also it’s the 30th anniversary of its publication in 1988. It was cutting-edge at the time. It asked all these big questions that sparked people’s imaginations. How was the universe began? How does time seem to flow in one direction, even though maybe there are some reasons why it should not? And are there other dimensions? Things like that– it was a real groundbreaking work.

And we want you to read it with us. So the first thing that I want people to know is that you can get a copy for free on our website at sciencefriday.com/bookclub. Jump in, sign up. We will pick 20 lucky winners. And then if you don’t win, you can get a discounted copy from Powell’s Books, because they are generously donating such things to us, as always.

And start reading with us. We will talk about it today. We will read for six weeks, and then jump back into the conversation with our guest readers at the end of August. And those readers are here today.

IRA FLATOW: And they are?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: They are– great question, Ira. They are two people who both think deeply about the universe as it is now and are also science communicators to some degree as well. So we have Priya Natarajan, who is a professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University and the author of Mapping the Heavens, which is all about some of those big ticket cosmological questions. And she joins us today. Hi, Priya.

PRIYA NATARAJAN: Yeah, hi, Christie. Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Hi there.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: And then we also have Clifford Johnson, who is another fantastic professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Southern California. He’s the author of that great comic book about cosmological questions, The Dialogues, which sort of breaks it down into really cool and accessible visual representations. And he also joins us today. Hey, Clifford.

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Hi, Ira and Christie. Pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for coming.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So we’re just going to dive into a little bit of why we should be excited to talk about this book right now. Priya, when did you first read A Brief History of Time?

PRIYA NATARAJAN: So I grew up in India, but I was in college at MIT when the book actually came out. And I was actually back home in Delhi that summer. And you know, I had to resist getting a pirated copy in paperback, because I hadn’t bought the hardback.

So I promptly came back from India, back to Boston, and bought my first copy. And it was deeply, deeply influential, especially, I think, the chapter on black holes, as you can imagine, right? It set me on a journey of falling in love with black holes and has really shaped my scientific interest over all these years.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: And Clifford, you reread the book for us just this week. How has it aged since graduate school?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: I think it’s aged pretty well. I think it’s still extremely striking as a book that, like nothing before it, I think, put a huge amount of what are considered very esoteric and mathematical sorts of concerns alongside concerns that we can all get to grips with– you know, how does time work, and how does the universe work, what have you. Put them together in this really great way. There are some things in there that are a little bit dated, but I think the core of the book is still very sort of sparkling with freshness.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Ira, we asked our Twitter listeners if any of them had read the book before today. And some 40%– so about 250 people responded, and only about 40% had read it. There’s this joke that A Brief History of Time is one of the most purchased, never read books of all time. It sold, like, millions of copies in the ’90s. Ira, had you read this before?

IRA FLATOW: You know, I read parts of it, but not the whole thing. You’re right. It was said that it was the greatest coffee table book ever written. No one wanted to admit that they didn’t read it, but they had it in their home. And in rereading it and reading parts for the first time, I’m just struck by two things.

One is what a great communicator Stephen Hawking was. I mean, how he could break down stuff into complex material, but make it sound very simple– big ideas and very simple. And two, I’ve been reading now these books for 30, 40 years, but forgetting how he laid the groundwork with the terminology, with the basis for what we now read in books later to come. Even some of the drawings were in there, in the first book. So it’s still fascinating now.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Tell me about those drawings, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: I mean, there was this light cone one. You know, it looks like– right? It looks like an hour glass when you look at it. I’ve seen it in current books, not realizing that Stephen had put it in that book 30 years ago. You know?

So it’s– and then also about when we talk about quantum, they give numbers, spin numbers to it. But I never really understood what the spin number actually meant. And he gives a very simple explanation about what the spin means. It’s just beautiful stuff.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah. I was going to say, I really like his sense of humor here and there. I mean, he introduces the book with, I think it’s a now-famous analogy, about turtles all the way down, which I don’t know, Priya, if you can sort of connect that to how we talk about physics.

PRIYA NATARAJAN: Yeah, no. I think that there’s a way in which he came up with analogies to give a sense for these cosmologically large numbers, to kind of make them tractable, and also talk about the concepts, the really complex concepts that we really didn’t have a scientific explanation for.

So for causation, for example, when people talked about– he talks about how when we think about the origin of the universe. Right? So we don’t yet have a fully scientific explanation. We are still working. And he had this analogy of how we could kind of keep reducing it and say, well, it’s turtles kind all the way down, right, holding things together.

And I think that coming back to the point about him being– you know, his stature as an international ambassador for science, I agree with Ira that he was sort of the original. He was the first guy. He believed so strongly in the need to communicate. And I think it’s his legacy now that there’s so many of us who realized how important it is to bring science to the public.

I happened to be at his service of thanksgiving in his memory, which was held at Westminster Abbey last month, of where his mortal remains were interred between the graves of Newton and Darwin. And it was a really, really moving occasion. And I think the– you know, his stature and how he touched people was just incredible. Right?

So there were a thousand members of the public who were going to be invited to the ceremony. And the Hawking Foundation said that there was a lottery by which they were selected. And 27,000 people from around the world had applied–

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Wow.

PRIYA NATARAJAN: –to be there.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah. And– oh, sorry, go ahead, Priya.

PRIYA NATARAJAN: No, I just think he was– you know, he is definitely one of the most influential communicators of science, and you know, really firm believer that it’s really important to share the awe, the curiosity about the cosmos, with the general public.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah. Clifford, when Hawking passed away in March, it very much felt to me like more people knew him as this famous person, this scientist who was famous. He was on The Simpsons. He was on Star Trek. He gave all these lectures. He had written these books. But what about his actual research? Do you think people really know what he contributed to science?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Well, I think most people don’t. And I think one of the things that makes him quite singular– well, at the time– was while there were massively popular people like Carl Sagan as well, I think they were very much perceived as maybe, rightly or wrongly, having stepped aside from research to do their popularization. Whereas he– I think people understood that he was still helping drive the field at various points. But that doesn’t mean that they knew exactly what he did.

One of the very striking things is that I, and many, many researches like me, are writing equations in our notebooks right now– in fact, I’m looking at one of my notebooks. And there are things in there that go directly back to his amazing work in the late ’60s and early ’70s on the quantum nature of black holes and things like that.

And he really sort of helped change the entire language of the field, and point up some crucial things. And that really is a legacy that will be there, whether or not he ever had written this book. And so that’s quite striking.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I mean, Priya what do we know about black holes, thanks to Stephen Hawking?

PRIYA NATARAJAN: Yeah. I think one of the most significant contributions that he made was that although we know of black holes as these monsters from which even light can’t escape, he realized that black holes actually give off thermal radiation. So this is not stuff that’s coming from inside the black hole, but stuff that’s coming from right around the periphery, from the event horizon.

And this radiation is referred to as Hawking radiation. It’s at very, very low temperatures for the black holes that we have evidence for, like the stellar-mass black holes that were recently detected by LIGO, the collision of these black holes and the gravitational waves, or the kind of supermassive black holes at the center of our galaxy and others, that people like me work on.

So the significance of this work was not so much the effect itself that the radiation was coming out, but the fact that he was able to provide a rather clear-cut physical sort of implication that brings together these two major theories in physics– the general relativity and quantum mechanics, and this sort of marriage that includes deeper notions from thermodynamics.

So this idea of black hole evaporation, although it’s not particularly relevant in terms of how long it takes– it takes an eternity for the kinds of black holes that we love and know and have observed so far. But this sort of attempt to bring this theory of the larger-scaled general relativity, combine it with the theory for the smallest-scaled, in this one instance around black holes, it was phenomenal.

And you know, sort of this deeper connection and a more overarching theory is something people are still sort of searching for. But this was an illustration of one setting where these two theories could really be powerfully combined.

I mean, I think this work on black holes, for me– look, this book is just absolutely wonderful. It’s exhilarating to read, still, right? But I think it’s the chapter on black holes– and I keep saying, chapter 7– I mean, that did it for me, and I think a lot of people of my generation. Right? He really debuted black holes for the public with this book.

And for me personally, sort of my reaction when I read this, especially chapter 7, I immediately went back to MIT, took a graduate course in general relativity that was taught, incidentally, by one of his former students, Nick Warner, using his notes.

So you know, I think it’s been deeply influential to share his work, both for people pursuing science and academic science professionally, but definitely for the public. His descriptions, as Ira mentioned, those lovely diagrams, simple as they were, not complicated, fancy graphics like we have today, but they conveyed a lot of the ideas and the conceptions.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: And we have to wrap this up in the next few minutes. But Clifford, in our last segment, we were talking about the recent neutrino discovery, which traced high-energy neutrino right back to this black hole called a blazar. This is exactly the kind of discovery Stephen would find exciting if he were still alive, right?

CLIFFORD JOHNSON: Yes. You know, it marks the coming together of many different kinds of physics, which also, I think, is an earmark of Stephen’s work. This is part of what people are now calling– and maybe that was mentioned in the previous segment– multimessenger astronomy, where we’re seeing different ways of looking at the sky– not just optical telescopes, but looking with neutrinos, and as Priya mentioned, looking with gravitational waves.

We’re seeing those different things come together in concert with other ways, like telescopes, to really change how much we can learn about the universe, possibly in a very revolutionary way. So being able to tag neutrinos and associate them with particular astronomical events in the sky is the beginning of a whole new lever we can pull to understand how the universe works. This is completely what Stephen would be excited about.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Great. Well, thank you both so much. Ira, I hope this has whetted your appetite to finish reading the book.

IRA FLATOW: Absolutely.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Great. So in order to encourage everyone else to participate, again, we are giving away 20 free books, thanks to the generous donation by Powell’s Books. And everything that you need to know about participating will be on our website, sciencefriday.com/bookclub.

Enter the giveaway. That will close by Sunday night. We will also have a link where you can buy a discounted copy from Powell’s Books, all book club long.

And then there’s a whole bunch of other stuff there. You can sign up for our newsletter, which will come out every Tuesday with extra resources for listening or for participating and learning and reading. We have a special call out to artists. We are commissioning art based on some of Stephen’s really fantastic analogies. We will pay you. Also again–

IRA FLATOW: Real money?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah, real money, not just science dollars, which I don’t know what those are– not neutrinos. And so we are calling out to artists to help us visualize these great words. We are having an event in New York City at the end of August, a time traveler cocktail party, in honor of Stephen Hawking having thrown one himself a long time ago. We are sending out the invitations in advance, unlike Stephen.

And then we also have a voicemail line. So that’s 567-243-2456, where you can call with your questions, your comments, your reactions, anything that crosses your mind as you’re reading. And of course, we are always on Twitter, #SciFriBookClub.

IRA FLATOW: How long is this going on?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: This is going on till the end of August– six weeks. August 24 is our wrap-up conversation with Priya and Clifford. We’ll have more of the same great discussion you just heard.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you both. Thanks to all three of you for taking time to be with us today. Priya Natarajan is a professor of physics and astrophysics at Yale University, and Clifford Johnson, professor of physics and astrophysics at the University of Southern California, also author of a great book, The Dialogue. And Priya has written Mapping the Heavens– couple of great books to add to this reading list also.

As we’re saying, we’re reading Stephen Hawking’s Brief History of Time. And joining us back on the air August 14 to discuss in depth, back with our panel to talk about the book when it’s all over.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.