The Seamstress And The Secrets Of The Argonaut Shell

Known since Aristotle, no one understood the argonaut octopus—until a 19th-century seamstress turned naturalist took it upon herself to solve its mysteries.

A greater argonaut (Argonauta argo) photographed in the Sea of Japan. Credit: Julian Finn, Museums Victoria

The ancient Greeks were masters of creating legends of the sea. In the epic quest, Jason and the Argonauts, a band of heroes aboard the Argo sailed the seas searching for the Golden Fleece that would grant Jason the authority of kingship. But these intrepid sailors aren’t the only nautical argonauts of Greek mythology.

The ancient Greeks were masters of creating legends of the sea. In the epic quest, Jason and the Argonauts, a band of heroes aboard the Argo sailed the seas searching for the Golden Fleece that would grant Jason the authority of kingship. But these intrepid sailors aren’t the only nautical argonauts of Greek mythology.

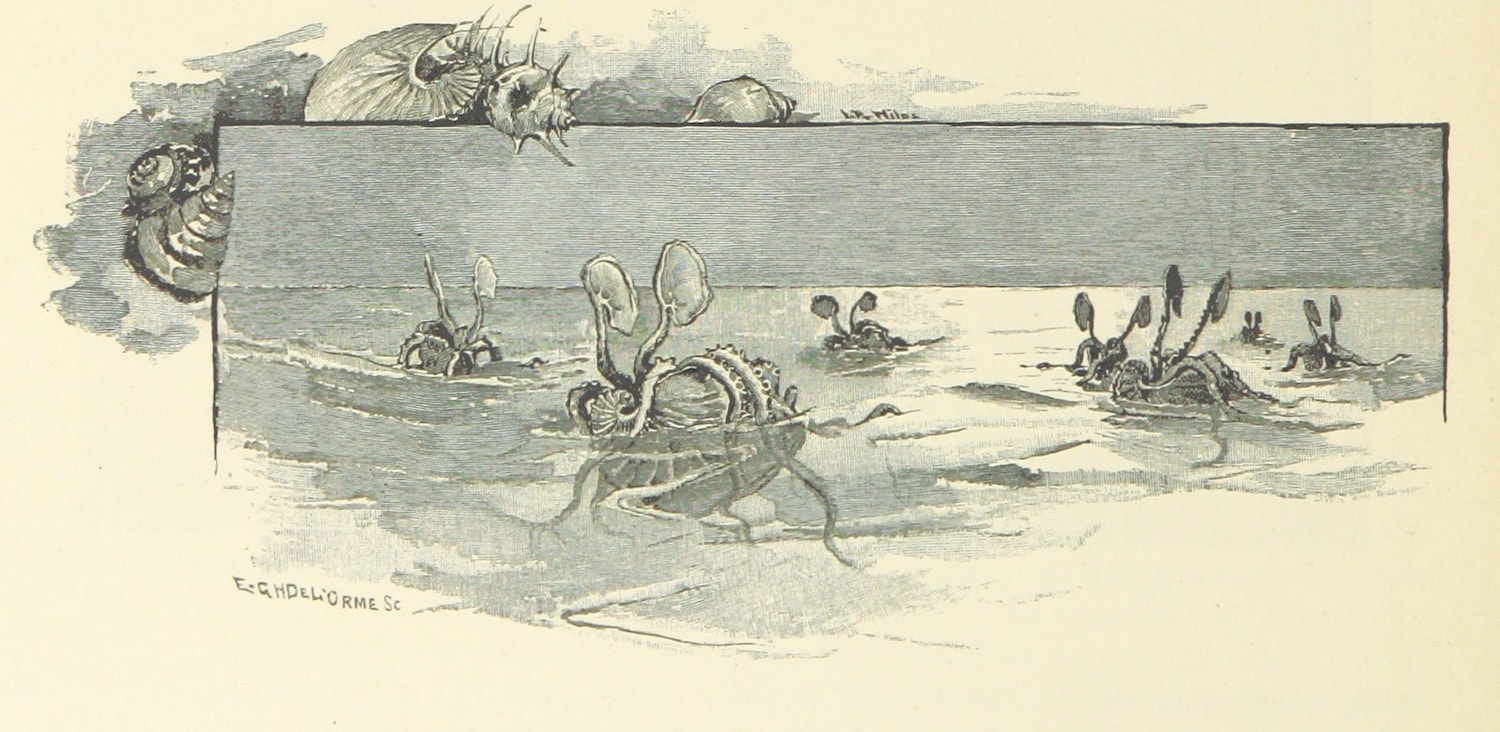

The argonaut octopus, of the family Argonautidae, belongs to a group of pale pink-spotted octopuses. Unlike the heroes that sailed the Argo, these octopuses are known for traversing the open ocean by way of a delicate, curved, creamy white vessel—an external casing, often referred to as a “shell,” that gave them their common nickname, the “paper nautilus.” These creatures baffled naturalists and philosophers for two millennia, even fooling Aristotle, who believed that they used their large pair of webbed dorsal arms as “a sail” to catch the briny breeze and floated across the ocean’s surface like paper boats. These myths carried weight for centuries, even among naturalists in the 19th century.

“This octopus was a problem because the descriptions were a little funny with the scientists describing it often with old, antique description—sketching it as a sailing octopus,” says Josquin Debaz, a science historian at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in France.

For about a decade, Villepreux-Power closely studied these “suspicious” yet “graceful” creatures. She became intimately acquainted with them, examining, experimenting, and describing everything from their feeding behaviors, movements, growth, and development. Unlike her predecessors, Villepreux-Power did not turn to dead specimens preserved in jars or “shells” washed up on the shore. She was determined to find a way to bring live specimens to the lab—and in the process, became one of the leading figures in a nascent aquarium boom. In fact, 19th-century English biologist and founder of the Natural History Museum of London Richard Owen referred to her as the “Mother of Aquariophily.”

“In her era, it was extremely unusual for a woman to get that opportunity at all, but it’s really nice to see that even then she could seize that opportunity and just be really good at it and be equal,” says Louise Allcock, an evolutionary biologist and cephalopod researcher at the National University of Ireland in Galway who wrote a paper cataloging Villepreux-Power’s work.

The four known living species of paper nautilus reside in tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters around the world. They feed on small crustaceans, mollusks, and jellyfish, using poison to immobilize their prey. Although they are rarely seen by humans in the wild, their “shells” have been collected in large numbers on beaches across the globe, sticking up from the sand like little cream-colored cornucopias. The abundance of shells washed up on shores after storms have led some to speculate that the argonauts may actually be quite common in the ocean.

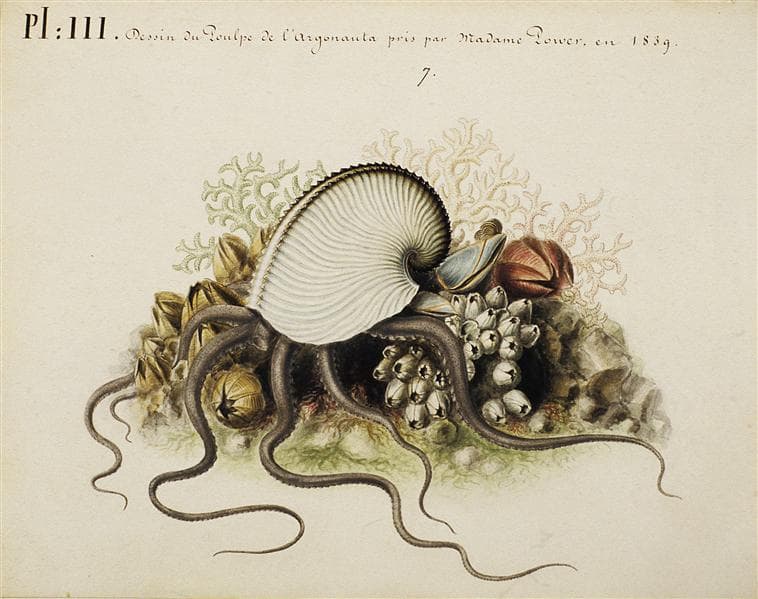

But the “shell” of a paper nautilus isn’t a shell at all. And confusingly, the paper nautilus is only distantly related to the chambered nautilus, the only living cephalopod with a true external shell, explains Allcock. Instead, the female paper nautilus carries a calcite egg case that protects and holds its eggs, because unlike bottom living octopuses, they dwell in the open ocean.

The female argonauts must have a way of brooding eggs in a structure that isn’t a cave or a den, says Julian Finn, senior curator of marine invertebrates at the Museum of Victoria in Melbourne. And they could be carrying a hefty load of precious cargo: Females can produce up to a million eggs in a lifetime, with individuals in some species found holding over 170,000 eggs at a time. “So the shell allows her to protect those eggs as they develop until they hatch,” Finn says.

Female argonaut (Argonauta argo), floating close to the sea surface in Okidomari Harbor, Sea of Japan. Credit: Julian Finn, Museums Victoria

In addition to holding eggs, the case helps the females stay buoyant in the open ocean. On dives, Finn has witnessed and described how the argonaut “gulps” and traps air in the egg case, allowing it to float, not on the surface as folklore depicted, but in the water column at neutral buoyancy. It’s more like Alexander the Great’s bathysphere than Aristotle’s sailing boat, Finn writes in Australian Science.

This thin, nearly translucent egg case plays an essential role in a female argonaut’s life cycle. But one big mystery divided scientists for centuries: Where did the shell come from?

In the 1800s, most scientists believed that the shell was made by another animal—that argonauts lived in them the same way that a hermit crab will go find a snail shell or a mollusk shell to live in, Finn says. Once the octopus grew too large for the shell, it would abandon the shelter and either search, steal, or kill the original inhabitant for a larger shell.

But, Jeanne Villepreux-Power sided with the opposite side of the debate: The argonauts were the builders of their cases.

“Everybody had their different opinions, but she took sort of an experimental approach and she broke it down and looked at it,” Finn says.

Villepreux-Power grew up nowhere near the ocean. Born on September 25, 1794 in the rural countryside of Juillac in central France, she came from a poor family and never received any formal education, explains Josquin Debaz. Eventually becoming a skilled seamstress and embroiderer in Paris, she worked on a wedding gown for a royal marriage where she met her husband, an Irish merchant James Power.

In 1816, Villepreux-Power moved to the Sicilian city of Messina. She drank up Sicily’s natural history and “she went all around the island and developed a good collection of minerals, plants, and animals,” Debaz explains.

Living near the seaside, Villepreux-Power wrote how the sea was as transparent and smooth as glass—it was so serene that she could see the smallest objects and most minute movements deep beneath the surface. Messina’s enclosed, sheltered bay provided ideal conditions for Villepreux-Power to make accurate observations on marine life. She wrote extensively on various species of marine mollusks and animals—including the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris). But Villepreux-Power was continuously drawn back to her “favorite the Polpo dell Argonauta.”

“When the air is calm, the sea calm, and it thinks itself unobserved, it is then that the Argonauta adorns [itself] with [its] beauties… Those [argonauts] who were used to seeing me for feedings showed me their beauties as peacocks do. It is at this moment that one can observe their movements and some of their habits.”

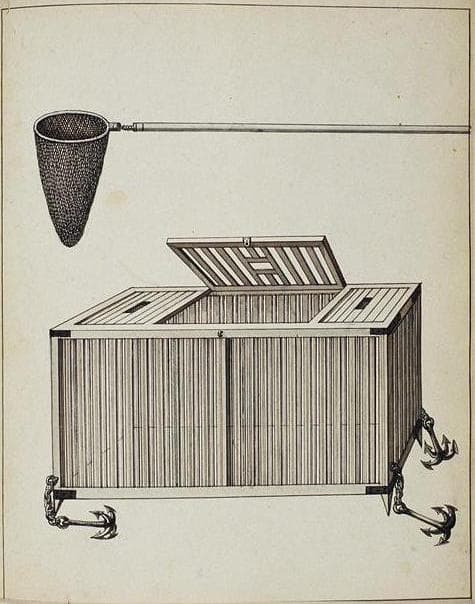

She set out to conduct a series of experiments on live argonauts—but in order to do that she needed aquariums, so she built her own.

Villepreux-Power started to build her aquariums in 1832. She worked with local sailors and fishermen who would bring her buckets of seawater filled with live argonauts. At first, Villepreux-Power filled her seaside home with glass tanks to try and keep the creatures, but unfortunately the animals didn’t survive in the enclosed conditions. Instead, she switched to designing several wooden observation cages—approximately four meters long, two meters high, and a meter wide—stationed in the clear, calm bay of Messina. Being closer to the natural habitat and residing in the circulating flow of the bay helped maintain the argonauts for longer periods of time. The creation of these tanks and crate stations placed her among the first pioneers to design early aquariums for research and observation of marine life.

“She devised a whole series of techniques that are quite practical responses, for example, she had to renew the water, she had to feed the animals,” says Jennifer Coston-Guarini, a researcher of marine historical ecology at the University of Western Brittany in France. “She’s basically working almost like a field ecologist or field zoologist and she’s quite methodical in her approach, which is in contrast to other people’s work [at the time].”

The 19th century was a pivotal time in modern biology. The field began moving away from ideas of the Enlightenment—classifying organisms, forming systematics, curating cabinets of curiosities—to thinking more about how organisms lived, Coston-Guarini explains. But this was a particular challenge for those who studied marine animals.

“You can’t go where they are. You have to bring it to you in some way to keep it alive,” Coston-Guarini says. With her observation stations on the bay, Villepreux-Power “could go out and observe the living organism and this idea is quite at the frontier of biological sciences at that time.”

A “shell” or egg case of a paper nautilus. When the shells are found dried out on the beach, they turn solid white and brittle. Credit: Nico.cec via Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

To unlock the mysteries of the argonaut’s egg case, Villepreux-Power conducted multiple experiments before coming up with the idea to damage the shell and observe the octopuses’ behavior. She punctured pieces of the shell of an individual and placed fragments from other argonaut shells into the cage. She watched for three to six hour increments, patience wearing thin, until right before her eyes she saw one argonaut repair its shell with the special membranes on its front two arms—the ones rumored to be used as sail. It was proof that the paper nautilus did create the egg case itself.

She noted how the membranes on the two dorsal arms, which secrete the calcite, moved over the opaque case with gentle craftsmanship. “Nobody before me… has seen how the Argonauta appears with its membranes extended on its shell,” she wrote. Close studies on the tissue of the thin, membranous webs have shown that they have calcium inclusions that are not found anywhere else on the female argonauts.

While they are not bound to the shell like some mollusks, the females start building the case as soon as they’re born and choose to stay in it for as long as they live. When the case is damaged, they can repair it with their specialized arms, as Villepreux-Power demonstrated. Each shell has variations in the folds, ripples, thickness, shape, and coloration that are unique to that individual. In fact, ongoing research by Julian Finn suggests that some specimens that have been classified as separate species based on differences in the sculpture of the shells may be more closely related than previously thought.

Villepreux-Power was also able to show that the shell was in fact an egg case by observing the octopuses during the fertilization and breeding season. From August to December, the argonauts increase their shells three times in size to provide enough space to hold their young.

Argonauts display an extreme form of sexual dimorphism. Females can be up to 12 times larger than males—the females grow to about a foot in length, while males remain about one centimeter long, just about as small as your fingernail. They are so small that while the females have been known since ancient times, the males have only been recognized for the last 165 years. The males fertilize the females by detaching a specialized arm—known as a hectocotylus—which carries the sperm.

While Villepreux-Power was never able to directly study male argonauts, she observed hectocotyli during her experiments. She believed that these wriggling appendages were part of the argonaut reproductive process, but she was rebuffed by the (mostly male) naturalists of her day who held that they were parasitic worms.

Villepreux-Power reported her results in a few publications and even presented at several institutions and academies throughout the 1830s. She belonged to at least 16 scientific societies and was the first female elected member of Italy’s Catania Academy of Natural Sciences. She wrote and published in Italian, French, and English and her work was translated into German, explains Debaz. “The reproduction in publication was proof at this time that she was a real success in publication,” he says.

Her work was widely received throughout Europe, and revered by Richard Owen and other prominent figures in science at the time. And while Villepreux-Power didn’t invent the aquarium, “she was one of the people leading the way at the time,” Coston-Guarini says. “If ‘the aquarium’ is the idea of keeping aquatic animals alive in some kind of container, then she’s one of the first people to have really put that idea into practice.”

“She found this path and she just continued and continued and she wasn’t deterred despite all this sort of controversy, and a lot of people who tried to discourage her along the way.”

However, there were others that were not as receptive of her argonaut research. One review in an 1839 issue of Magazine of Natural History stated that her reports were sometimes “evidently inaccurate,” which could be “a consequence resulting from her want of physiological knowledge, and partly from a very natural wish on her part not to appear ignorant of things which she supposed every body knew [sic].” In 1837, French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville claimed at the Paris Academy that her results and conclusions were erroneous, still strongly supporting that the argonaut merely inhabited but did not produce the egg case shell, while others asked that she repeat and demonstrate portions of her experiment, says Debaz. Villepreux-Power also wrote of an instance where French malacologist Sander Rang presented one of her papers as his own, Debaz says.

Still, the challenges didn’t dissuade Villepreux-Power’s persistence or scientific pursuits.

“She found this path and she just continued and continued and she wasn’t deterred despite all this sort of controversy, and a lot of people who tried to discourage her along the way,” Coston-Guarini says.

Villepreux-Power continued to do research well into the 1840s, including publishing a guide to Sicily’s natural history in 1842 and her paper on Octopus vulgaris in 1860. However, she and her husband unexpectedly left Messina to move to London, and she had to suspend her work on the argonaut in 1843. That same year, a ship transporting much of her books, writings, and collections sunk, causing history to lose trace of her scientific findings on the argonaut. She died at the age of 77 in 1871 in her hometown Juillac, France.

“If I trace back the idea at that time that argonauts could repair the shell and therefore were the animal that made the shell, that came from Jeanne Villepreux-Power’s work,” Julian Finn says. “I don’t think anybody else has spent more than 10 years looking at argonauts. She had a lot of insights and probably a lot of insight that didn’t go into the publications that came out.”

But despite the years of research forgotten and lost to the sea, Villepreux-Power’s studies on the argonaut live on. Her practices and work completed centuries ago are reflected both in the glass tanks of modern-day aquariums and research stations that bring a little bit of the sea’s splendor to the surface, and in the scientists who go out and observe wildlife in their natural environments.

“Essentially, she works the same way I like to work,” he says. “You look at the animal and let it explain itself to you.”

Special thanks to Annie Nero and Natalia Stricker for their assistance with translating French texts.

With every donation of $8 (for every day of Cephalopod Week), you can sponsor a different illustrated cephalopod. The cephalopod badge along with your first name and city will be a part of our Sea of Supporters!

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.