The Making Of The Octopus In ‘20,000 Leagues Under The Sea’

In the first major underwater film production, three key inventions helped create an iconic scene featuring an impossibly large cephalopod.

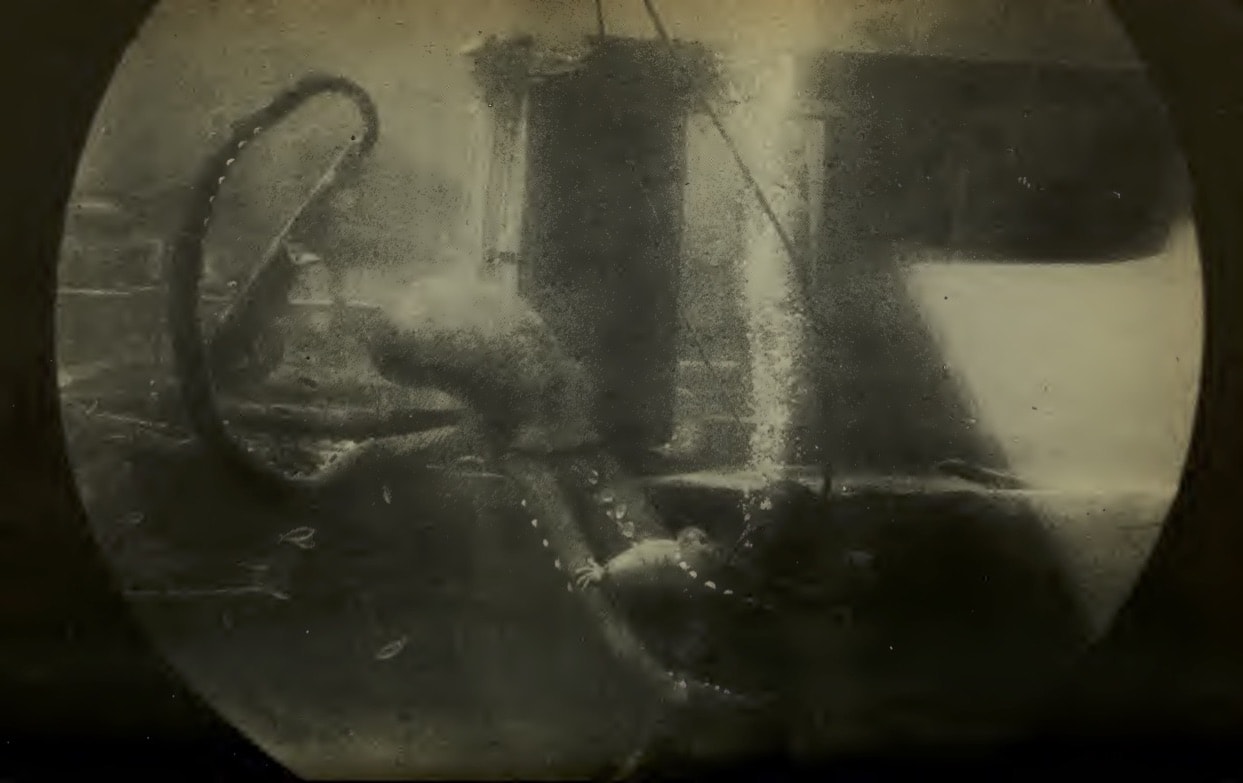

The scene begins innocently enough. An unsuspecting pearl fisher paddles through the water, going about his business. Waves gently buffet the diver as he nears a coral reef, and crabs scuttle into their holes. Then, a single sinewy arm of an octopus snakes through the water, closing in on the diver.

The scene from the 1916 film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was shocking to audiences. “Undersea filmmaking pioneer” John Ernest Williamson reflects on the scene that he helped create: “The [sight] of that great pulpy body, those great staring eyes, those snake-like sucker-armed tentacles [sic], sent a chill of horror down my spine,” he writes in his memoir 20 Years Under the Sea. “The giant cuttle-fish glided with sinuous motion from its lair. Loathsome, uncanny, monstrous, a very demon of the deep, the octopus was a thing to inspire terror in the stoutest hearts.” (While Jules Verne’s original novel often features a giant squid when translated into English, Williamson refers to his creation for the 1916 film as an octopus.)

Moviegoers were held rapt as Captain Nemo dove into the water and battled with the impossibly large cephalopod, eventually hacking off one of its writhing arms, freeing the pearl fisher, and fleeing in a cloud of the creature’s ink. They were sucked in not only by the terror it inspired but also by its technical innovations. The battle, and great octopus, was the centerpiece of the first major motion picture to be filmed underwater.

Had it been produced under normal circumstances of the time, writes underwater cinema scholar Jon Crylen, this iconic battle scene would have been filmed on a set against a backdrop of painted waves, or an aquarium may have sat in the foreground while actors played the scene behind it. But thanks to three inventions, Williamson could bring audiences face to face with a great “cephalopod” under the sea.

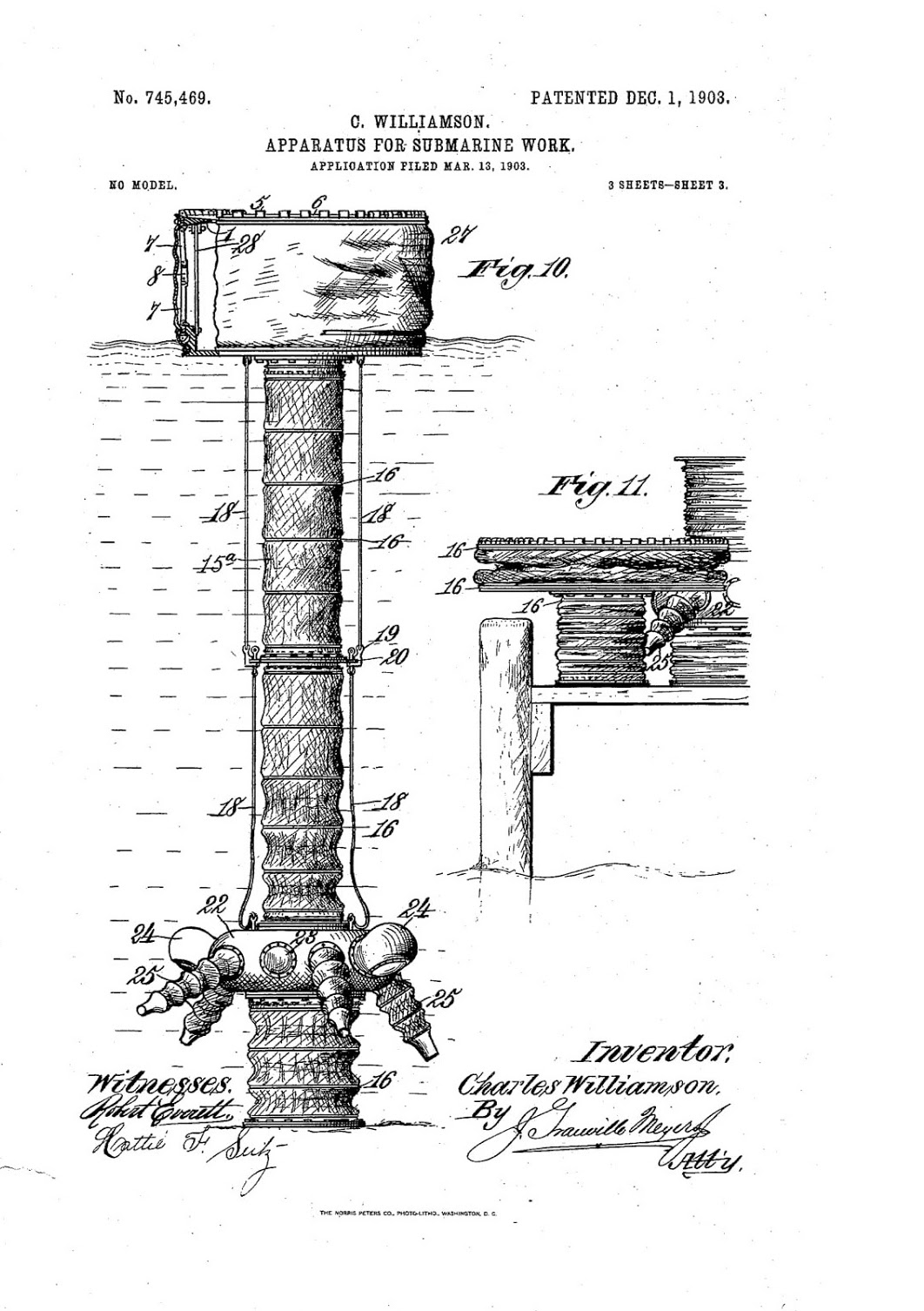

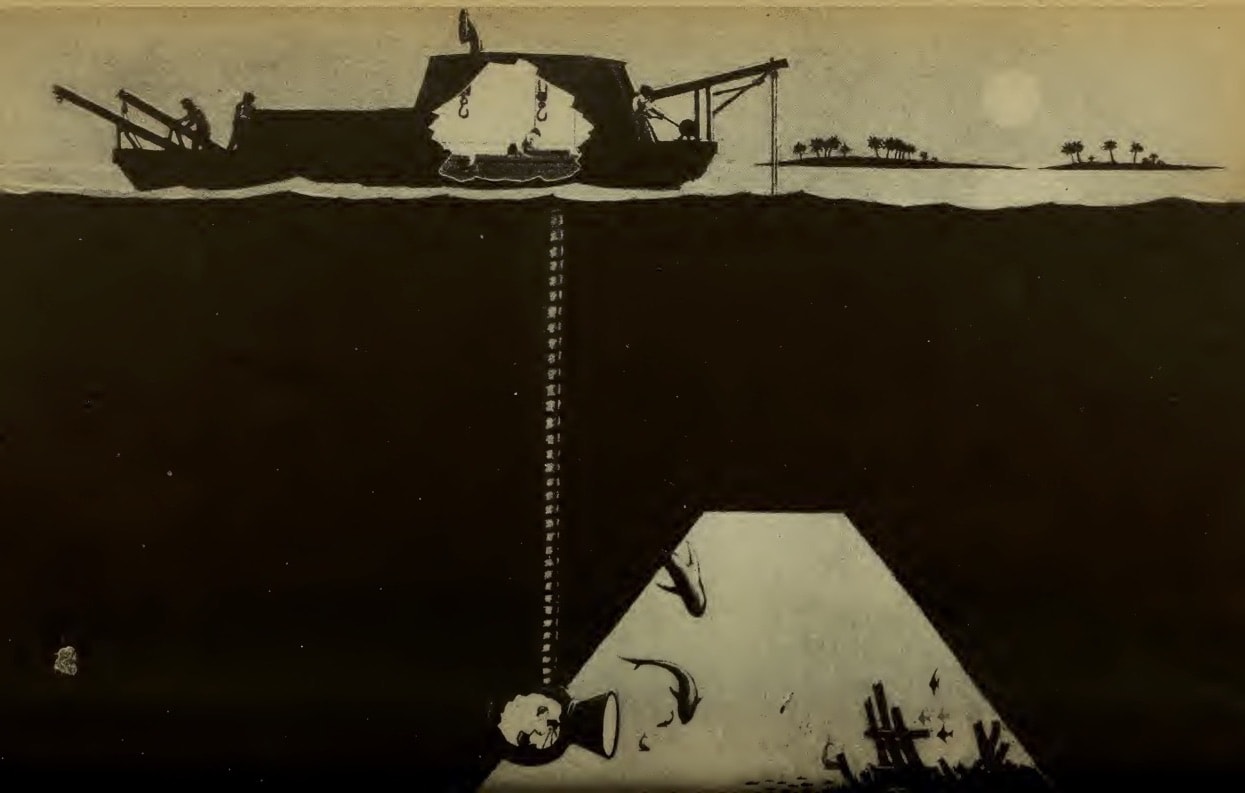

Williamson’s father, Charles, first envisioned what would come to be known as the submarine tube—but he wasn’t looking to make movies. A sea captain from Virginia, Charles wanted to ensure the tube was completely watertight for submarine engineering and salvaging shipwrecks, writes Crylen. His device consisted of a collapsible tube attached to a floating barge, ending in a in a helmet chamber with arm casings so operators could move underwater. But the device never took off in the world of engineering—it was considered too cumbersome—and it was cast aside until J.E. began to dabble in undersea filmmaking and repurposed the tube. “In lending me his invention I am sure he felt very much like a mother who gives over her only child for a dangerous surgical operation,” the younger Williamson writes of his father, “yet he agreed to let me go ahead.”

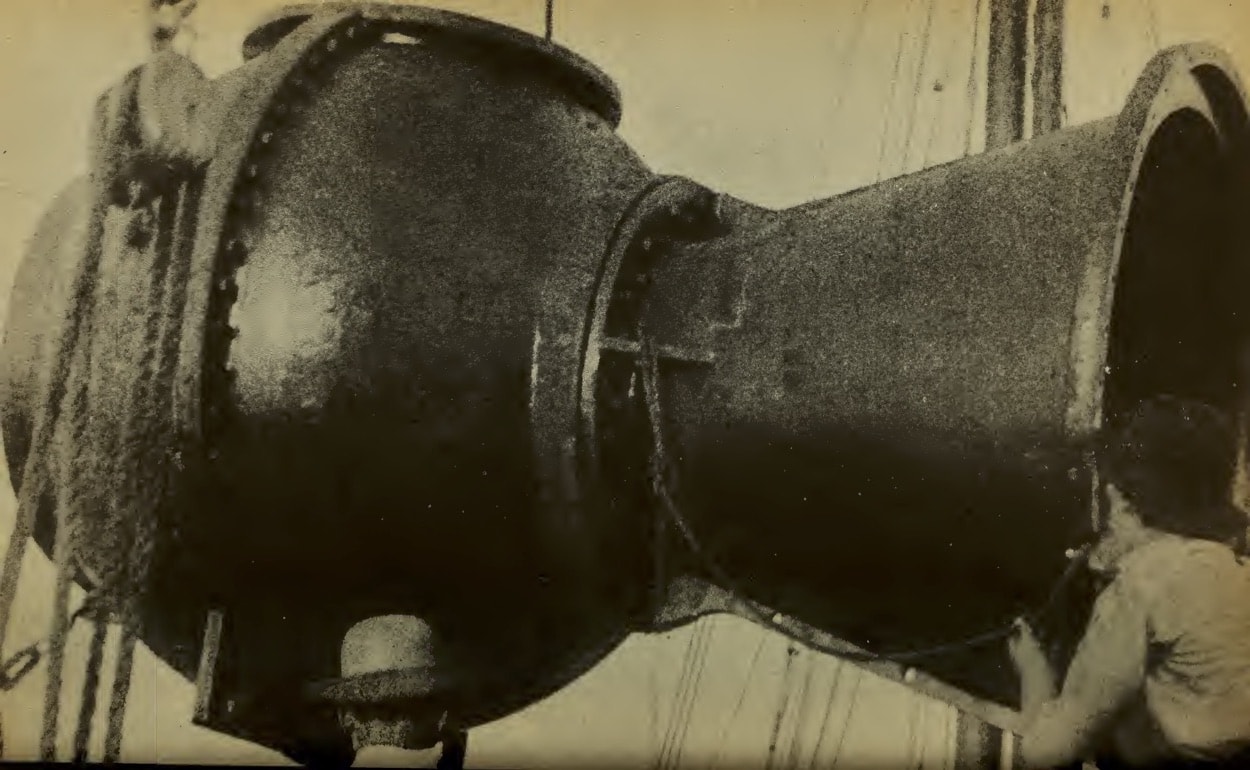

Now that he could dive deep, Williamson needed to find a way to bring his camera down as well. After sleepless nights spent stewing over the problem, he devised the “photosphere,” a 6×10-foot steel globe that weighed four tons. The photosphere included a conical viewing chamber that could safely house a camera. It attached to the submarine tube, allowing Williamson to direct scenes from the deck by shouting his orders down from the vessel, writes Crylen.

Over and over again, I focussed my camera and pressed the shutter, filled with tense excitement, nerves a-tingle. Would my experiment be a success?

When he tested the device for the first time, he was in awe: “All about my chamber, undisturbed by the strange invader of their realm, the fishes swam lazily through the green sea water or stopped to peer curiously into the glass of my window,” he writes. “Over and over again, I focussed my camera and pressed the shutter, filled with tense excitement, nerves a-tingle. Would my experiment be a success?”

Back on land and in the darkroom, Williamson anxiously watched as the lines in the photograph darkened and fishes and underwater plants slowly emerged. The use of the photosphere and submarine tube in tandem had worked—and they became key to Williamson’s films.

When Williamson decided to tackle the iconic Jules Verne novel for his next film, he knew he had one important piece missing: “The octopus was my brain-child,” he writes. “It was not spawned in the open sea, but in a tumultuous sea of production details.”

[One day, octopuses may be as ubiquitous in labs as mice.]

The filmmaker was initially determined to hunt down a live giant cephalopod—but he was also dead set that the octopus in the film would stretch to an unparalleled 30 feet. He’d heard of octopuses of roughly 20 feet, but a real cephalopod of that scale remained elusive and production time was closing in.

With a real 30-foot octopus out of the question, Williamson set to work creating his own. He modeled his creation after a specimen at the Brooklyn Museum, which was reproduced from measurements from a real cephalopod.

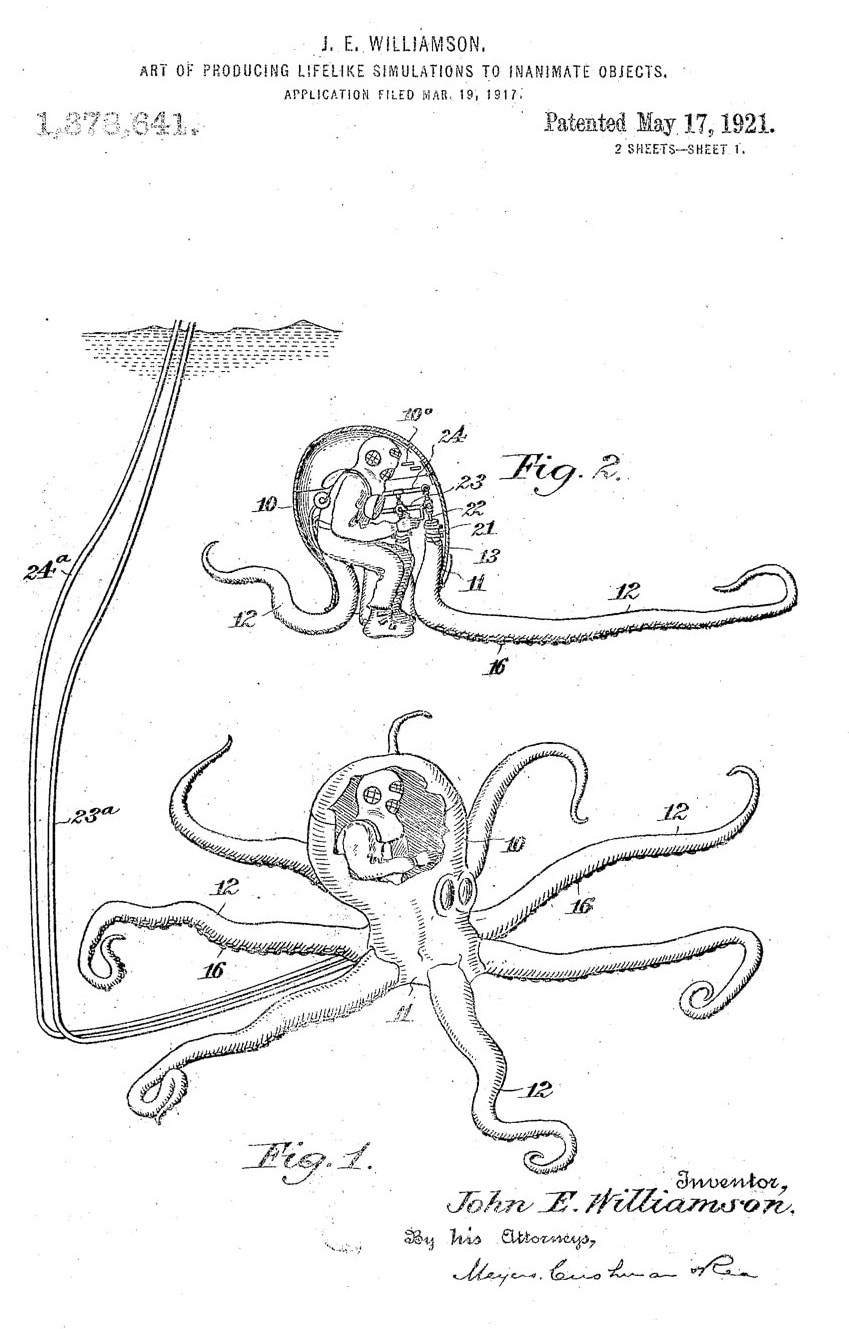

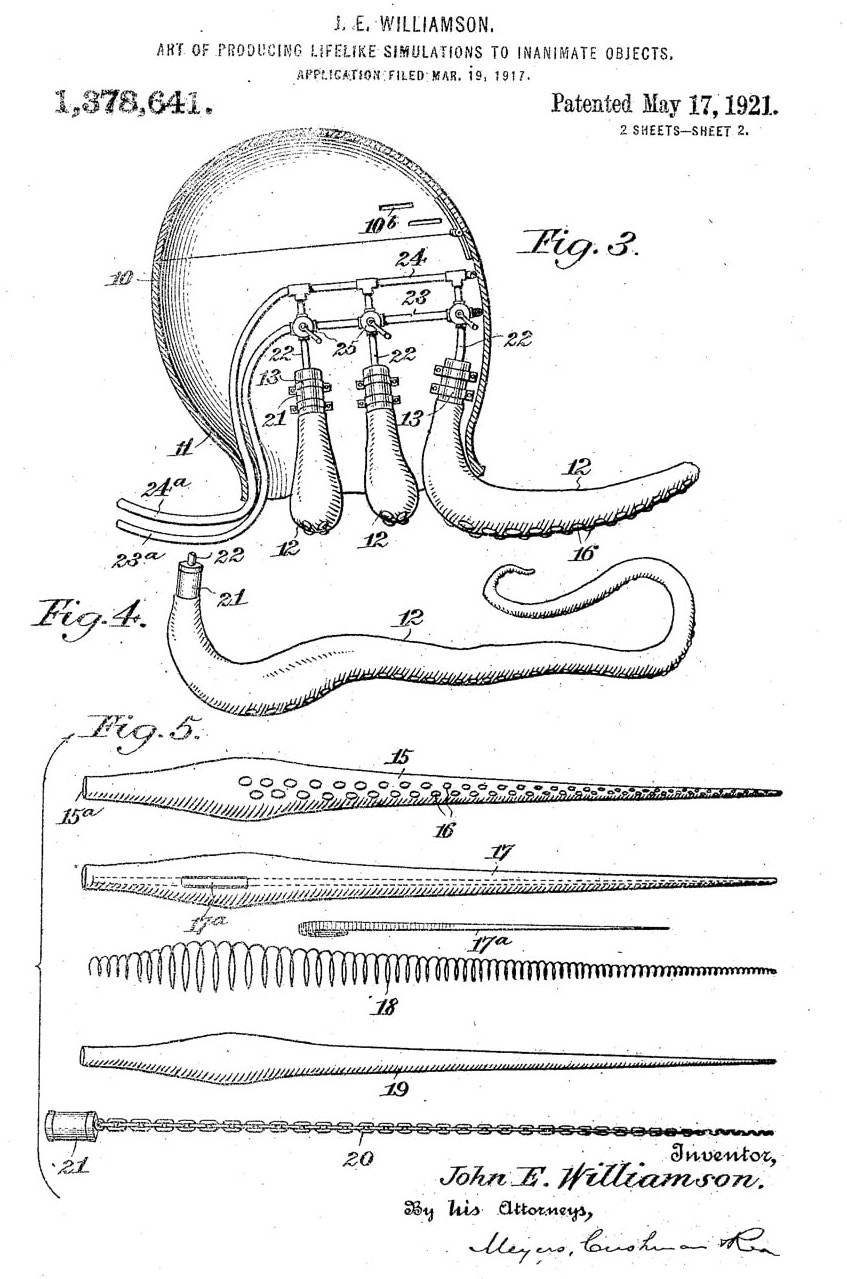

Williamson began with the octopus’ arm. He knew “it must writhe and squirm and reach out and take hold of objects, draw them in, coil round them like a python, to resemble in every detail the deadly arm of an octopus.” To recreate the writhing movements, he produced tapered springs that extended and recoiled, and covered them with a rubber tubes. When the operator—who crouched inside the creature’s head and operated the device via levers and controls—shot a burst of compressed air through the arm, it would straighten and then pull back, mimicking the movement of a real octopus. Using halved rubber balls as suckers would complete the illusion.

But one final question remained: How would the octopus execute its “most spectacular function,” the expulsion of its characteristic ink? Williamson first tested gallons of writing ink, but it was too dark to be realistic. One day, one of the divers working on the film dredged up some marl, or sediment often used as fertilizer, from a swamp. When the filmmaker dropped some of the marl into the ocean, he noticed that it dissolved into “a perfect sepia ink.” Williamson ordered a truck-full, and pumped it into the octopus.

[Bobtail squid + Bacteria + BFF]

“Finally I had it all tuned up to perfection,” Williamson writes. “My creature could now move bodily about, throw its cloud of death, and shoot out its terrifying tentacles [sic] at will—my will.”

Williamson and his engineering marvels cracked open a new world. He created a series of both narrative fiction and documentary films in the Bahamas over the course of nearly 20 years, and through these innovations, Williamson and his team conjured scenes of mermaids, sunken treasure, and other undersea wonders—but Jules Verne’s giant octopus was what first captivated moviegoers in 1916.

Perhaps these words from a 1917 edition of The Oakley Herald best describe these new undersea visions: The film “[flashed] before the eyes of the world the most enthralling scenes from the bed of the ocean, maritime marvels for countless thousands of years denied the sight of mankind. A stupendous, spectacular production… showing in actual use, inventions which have made possible the freedom of the ocean depths to human beings.”

Editor’s Note: This piece was updated to clarify the discrepancy between references to the giant cephalopod as a “squid” in English translations of Verne’s novel, and “octopus” in the 1916 film.

With every donation of $8 (for every day of Cephalopod Week), you can sponsor a different illustrated cephalopod. The cephalopod badge along with your first name and city will be a part of our Sea of Supporters!

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.