Marine Habitats Are Protected—But Are They Effective?

4:50 minutes

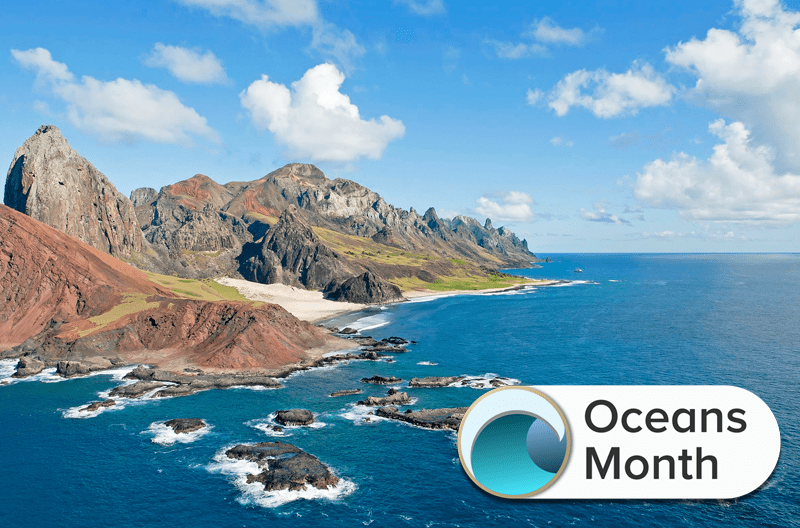

This is a part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

This is a part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

Earlier this year Brazil made headlines and received accolades from ocean conservation advocates for turning 900,000 square kilometers of ocean in its exclusive economic zone into a marine protected area. Brazil is just one of many countries who have made a commitment as part of the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity to protect 10 percent of the world’s oceans by 2020. That’s the good news. But the question remains: Does that 10 percent really need protecting? Natalie Ban, associate professor at the University of Victoria, joins Ira to explain how some countries are using ocean conservation to score political points and whether anything should be done about it.

Natalie Ban is an associate professor in the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

IRA FLATOW: Now, it’s time to play Good Thing, Bad Thing–

[MUSIC PLAYING]

–because every story has a flip side.

Now, you may remember earlier this year, when Brazil turned a 900,000 square kilometer-swath of open ocean into a marine protected area, and it’s not just Brazil. By the year 2020, nearly 10% of the world’s oceans should be protected thanks to a formal commitment made by many world governments to ocean conservation. That’s the good news.

The question is, are we protecting the wrong places? Here to tell us the good and the bad news of the new ocean conservation effort is Natalie Ban, associate professor in the School of Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. Dr. Ban, welcome to “Science Friday.”

NATALIE BAN: Thank you so much, and happy Oceans Day to you.

IRA FLATOW: Happy Oceans Day to you. So the governments signed on to protect 10% of the world’s oceans by 2020. How are they doing, in terms of meeting that goal so far?

NATALIE BAN: So so far, we’re not quite there yet. Globally, we have about just over 3% of the oceans protected, of which about 2% is highly protected. So we’re still a long ways off that 10%. But that target has really energized a lot of countries to try to meet the deadline by 2020 to protect that percentage of their oceans.

And there are some countries that have really gone a long, long way towards it, much more so than what would have been expected. So for example Palau, an island nation, has protected about 80% of its ocean estates, of its exclusive economic zone.

And earlier this year, there was a big announcement that the Seychelles, another island country, did a big debt-for-nature swap. So they protected a large portion of their marine area in return for getting some of their debt forgiven.

IRA FLATOW: Now that’s the good news. What is the bad news, besides the fact the US is not a member of this agreement?

NATALIE BAN: Well, the bad news is that this target by the Convention on Biological Diversity includes in it that 10% of the oceans should be protected. And it’s got a bunch of other stuff that’s actually really important like that those areas should be important to biodiversity, that they should be equitably managed, ecologically represented, and so on.

But what countries have latched onto is just that 10%. So you mentioned the example of Brazil. Brazil has protected, in total, about 26% of its ocean area, and you know that sounds fabulous. But the two places that it added are way offshore. Nobody goes there. They’re not currently actually threatened, and the problem is that some countries are playing this political game of trying to meet that target without actually protecting the places, especially near shore and near people that really need the protection.

IRA FLATOW: So how do you overcome this then?

NATALIE BAN: Well, in part, we need commitments to really protect the oceans from the threats that exist to them. So it means that we can’t just protect the large offshore areas, some of which are really important to protect. We just need to make sure that protecting those large offshore places doesn’t come at the expense of also doing conservation in places that are near shore, near people, and so on.

So it’s really important to look at these other aspects of this target, not just the percentage. But if we represented all of our marine ecosystems, so say, for example, coral reefs and rocky reefs and sandy areas and estuaries and ensured that 10% of all of those ecosystems and habitats were protected. Then just protecting that giant offshore area wouldn’t actually help meet the target as much as it does right now, when we’re only looking at the percentage target.

IRA FLATOW: So we have to do the hard work, too, where it’s hard to do, not just the easy stuff.

NATALIE BAN: Well, that’s exactly right. It can be politically expedient to protect places where nobody goes. And it’s kind of equivalent to on land, where there’s the phrase we just protect rock and ice. The high mountain tops with glaciers that are beautiful but don’t necessarily have all of those threats. That’s not the places that are being developed and in the ocean that are being fished or mined or have coastal development and so on.

And yes, I think it’s important to also protect those remote wilderness, if you will, places, but we can’t only do that. We need to also focus our efforts on the more threatened places, because that’s really where biodiversity is hurting. That’s where fish stocks are threatened, where mining is taking place and so on.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Ban, thank you very much for taking the time to be with us. Natalie Ban, the University of Victoria in British Columbia.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.