Forget Weather, These Bots Make Good Conversation

12:29 minutes

Should autonomy be the holy grail of artificial intelligence? Computer scientist Justine Cassell has been working for decades on interdependence instead—AI that can hold conversations with us, teach us, and otherwise develop good rapport with us. She joined Ira live on stage at the Carnegie Library of Homestead Music Hall in Pittsburgh to introduce us to SARA, a virtual assistant that helped world leaders navigate the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland last year. Cassell discusses the value of studying relationships in building a new generation of more trustworthy AI.

[Science Friday is hitting the road to Chicago!]

Credit: courtesy Justine Cassell

Justine Cassell is Associate Dean in the School of Computer Science and the former director of the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow coming to you from the Carnegie Library Music Hall in Pittsburgh.

[APPLAUSE]

Yeah. You know, bit by bit, artificial intelligence is working its way into our lives. And it’s not just self-driving cars. Look at AI assistants that live in our smartphones, like Siri, or the ones that we’ve added to our homes like Alexa. Someday, maybe soon, AI may be making phone calls to schedule your doctor’s appointments, or even helping your children in the classroom with social skills or creativity.

But for AI to be most helpful to us, we have to trust it– trust it enough to share our personal secrets. And that’s where my first guest comes in. She spent her career studying how we build trust with each other, and then with virtual personalities. And the key, she says, isn’t necessarily building knowledge, but rather asking questions, making small talk, and opening up to one another.

Justine Cassell is associate dean of the School of Computer Science, and former director of the Human Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University. Welcome, Justine.

JUSTINE CASSELL: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: It’s great to have you.

[APPLAUSE]

Now, I know your work focuses on artificial intelligence that has a visual component, like an animated face. When not go straight to making physical robots with bodies on them?

JUSTINE CASSELL: Well, it’s true. My work is more like cartoons on a screen. And that’s because we can still do more realistic kinds of movements with a cartoon than we can with a robot.

IRA FLATOW: We have a video that actually demonstrates one of your projects called SARA, the Socially Aware Robotic Assistance. Before we look at it, tell us a bit about.

JUSTINE CASSELL: So SARA, Socially Aware Robotic Assistant, is a personal assistant. We were asked to create this for the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos in 2017. And so more than 300 world leaders interacted with SARA. And SARA helped them meet other people at the same level of importance as they are, and helped them find sessions to attend that match their interests.

Doing that required them to disclose information about themselves. And in fact, it turns out that self-disclosure is one of the ways we build rapport with other people. So she had to get them to self-disclose. And she did that by asking questions about them, but also by self-disclose about herself. Like, gee, this is my first time here. It’s pretty awe-inspiring. I’m kind of freaked out. Are you freaked out at all?

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s go take a look. Let’s go watch the video and take a look at how that happened.

SARA: Hi. I’m SARA. It’s such a pleasure to meet you. Might I ask your name?

SPEAKER: Hey, SARA. My name is [INAUDIBLE].

SARA: Nice of you to take the time to stop by. So how are things?

SPEAKER: It’s going pretty good. It’s going pretty good.

SARA: Great. Well, let me introduce myself. I’ve been asked to play matchmaker by helping attendees find sessions to attend and people to meet based on their interests. All you need to do is tell me a little bit about yourself and what you want to do while you’re here.

SPEAKER: So I am a master’s student at Carnegie Mellon University in the computer science department. And my research focuses on artificial intelligence and natural language processing. And I’m mainly here just to network, meet people in the tech scene, and maybe go to some interesting sessions.

SARA: I’ve never met someone like you before. It’s refreshing. Let’s see if we can find some interesting people to meet. Just one minute while I look this up. There are details on the screen about Justine Cassell. I feel you share some interests.

SPEAKER: Yeah, Justine Cassell. I’ve heard of her. It would be nice to meet her, though.

SARA: I can either send a message on your behalf suggesting a meeting, or I can give you the information and you can set up the meeting yourself. Would you like me to send the message?

SPEAKER: Yeah, please do.

SARA: Oh, good. You’ll see a message from me in your TopLink private message inbox introducing you two.

SPEAKER: Awesome.

IRA FLATOW: Awesome. Awesome. Yeah, that was a great, great video.

[APPLAUSE]

You know, it would seem to me from looking at the video is she wasn’t just talking. She was doing a lot of things at the same time.

JUSTINE CASSELL: Right.

IRA FLATOW: There was not a real script that she was reading from.

JUSTINE CASSELL: No, she’s actually adapting her behavior to the behavior of the person she’s interacting with. And what we saw was that she’s automatically sensing what conversational strategy that people are using. Are they self disclosing? Are they praising her? Are they teasing her? Violating social norms in some way? And then she adopts what she says in order to raise rapport. And you could see rapport rising.

And what’s interesting about SARA is that it’s the first project that considers both what’s going on in the human and what’s going on in the computational agent in order to figure out where the rapport is in place.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we talked about having to gain trust from a computer. That seems to be a key. You keep mentioning over and over again rapport.

JUSTINE CASSELL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Right, you have to build a rapport. So that’s where the trust comes from.

JUSTINE CASSELL: Trust does come from rapport a lot. Yep.

IRA FLATOW: And so why do we need a physical face on SARA at all up there? Does that help build that trust or rapport?

JUSTINE CASSELL: It’s a really good question. I’m really not for embodied agents just because they’re cute or cool, but because we use our bodies in ways that demonstrate how we feel about the other person, where we are in the conversation. And so we need bodies on agents like this because in our conversation– and I’m certainly an example. I’m trying not to knock this microphone off while I gesture. We use our hands, and our face, and our torso to indicate who we are to the other person, who the other person is to us.

IRA FLATOW: So that body language–

JUSTINE CASSELL: Body language is important.

IRA FLATOW: –body language. So how is SARA a step up from, say, Alexa, or Siri, or any of those other–

JUSTINE CASSELL: Where shall I begin?

IRA FLATOW: Let me count the ways.

JUSTINE CASSELL: So SARA, first of all, does have a body, unlike Alexa, or Cortana, or any one of the current personal assistants that are out there made by these major corporations. And she uses her bodies in the ways that I just described– to build trust. To build rapport. To build confidence in what she says.

But she also, unlike those agents is– while she’s talking, she’s automatically sensing your response. So she’s looking to see whether you’re smiling, you’re looking at her, your eye gaze is towards her or away from her. And she’s using those cues as well as what you say to decide how you feel about her.

IRA FLATOW: What’s hard about making AI that can interact realistically with humans? What’s the hardest part?

JUSTINE CASSELL: We are unpredictable as humans.

IRA FLATOW: You think?

JUSTINE CASSELL: Yeah. Long years of study before I understood that. And SARA has to be able to keep up. She has to be able, in real time, to do what we call classify– that’s a machine learning term– classify the conversational strategies you’re using. And so you saw her doing that. She chooses one of eight strategies.

That’s really hard. And you need a lot of data in order to get it right. But the kinds of phenomena that I’m interested in– these things like being polite or violating social norms– don’t happen all that frequently in conversation. So what you’ve all heard of referred to as big data, these kinds of phenomena– the ones that are really important in interaction– are small data. And that makes it hard.

IRA FLATOW: It’s interesting. You showed us what was going on at the World Economic Forum– a lot of rich people up there in Switzerland. But let’s bring it down to Earth more. What kind of practical solutions can you use SARA for that we can relate to?

JUSTINE CASSELL: Yeah. So SARA is a platform, in fact, a set of computational modules that work together that can be used for really any purpose, as long as you put them together in the right way and add a kind of a functionality.

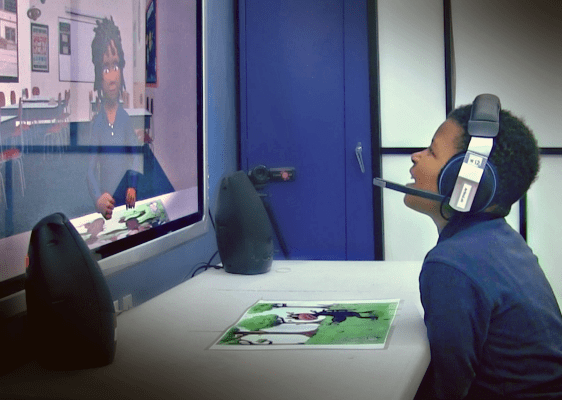

And so we have a system called RAPT, the Rapport Aligning Peer Tutor, who looks like a teenager and who peer tutors teenagers in linear algebra. And it builds rapport in order to help the student learn. And we know in human-human interaction– and all of my work is based on looking at real humans in interaction with other humans. We know that when kids feel rapport with another kid, they learn more.

And a second thing that we’re building is called SCIPR– we’re big into acronyms, as you can tell. And SCIPR stands for Sensing Curiosity in Play and Responding. Took us a long time to come up with that one. And SCIPR is for younger children, eight or nine-year-olds.

Now, in the contemporary school system, there is a lot of teaching to the test because today in America, schools get funding as a function of how well the students do. And teaching to the test is pretty much antithetical to curiosity, to passionate curiosity like you and Einstein. How do we keep–

IRA FLATOW: Don’t put us in the same–

JUSTINE CASSELL: I’m trying to get on your good side.

IRA FLATOW: Bill Nye would be close enough.

JUSTINE CASSELL: So how do we get kids to remain curious about their world? Because really, curiosity is the key to exploration, which is the key to learning. And so SCIPR doesn’t build rapport. It builds a sense of curiosity in groups of children by watching what they do and capitalizing on those of their behaviors that are leading them towards being curious.

It’s the first project where we’ve worked with groups of kids. So it’s not just a twosome, it’s three to four kids. And the first time we’ve worked with curiosity.

IRA FLATOW: How do you know it’s successful? How do you know it’s working?

JUSTINE CASSELL: That’s the million dollar question. We have to evaluate all of this. Now, we’re in the process of testing RAPT, the teen linear algebra tutor with– so far, I think we’ve worked with 50 teenagers. And what we’re looking at is their learning gains. That’s the only thing that really matters. Who learns more? The kids who interacted with the version that builds rapport, or the kids who interacted with the other version that doesn’t build rapport?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well, I wish you great luck– great success and good luck with your work.

JUSTINE CASSELL: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Justin Cassell– Dr. Cassell is associate dean in the School of Computer Science and former director of the Human Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University here in Pittsburgh. Thank you for taking time to be here with us.

[APPLAUSE]

After the break, we’ll look at building robots that we can trust and empathize with, and where art and psychology fit. I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.