These Eyebrows Speak Volumes

11:33 minutes

The eyes may be the window to the soul, but it’s our eyebrows that’re doing all the talking. When you see someone you recognize, you can give them the “eyebrow flash.” Want to convey sympathy or concern? A furrowed brow is best for that. And nothing says “I’m skeptical of you” like a single arched eyebrow.

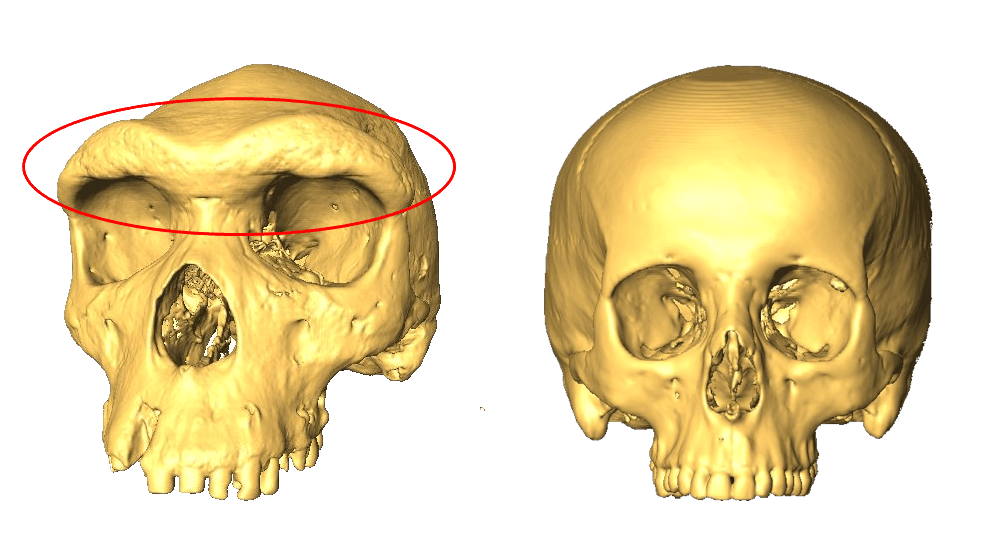

The ability to wiggle those two hairy features around isn’t just some party trick, it’s almost like a secret language—one that even our ancient ancestors used to their advantage. Using computer modeling to manipulate the fossilized skull of Kabwe, a member of the subspecies Homo heidelbergensis, researchers ruled out a mechanical purpose for the protruding brow ridge of our ancient ancestors. Instead they turned to an alternative explanation—that moveable eyebrows proved useful for communication, especially for pro-social displays of emotion like recognition and sympathy.

[Hey NYC! It’s time to get your science trivia on.]

Penny Spikins joins Ira to discuss how wiggling eyebrows may have been among some of our earliest forms of communication.

Penny Spikins is a senior lecturer in the Archaeology of Human Origins at the University of York in York, United Kingdom.

IRA FLATOw: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The eyes may be the window into the soul, but you might argue that it’s our eyebrows that are doing all the talking. Let me tell you what I mean. Like, if you see someone you recognize, you give them the eyebrow flash. You want to convey sympathy or concern. A furrowed brow is best for that. And nothing says I’m skeptical of you like a single arched eyebrow.

Yes, the ability to wiggle those two hairy highlights isn’t just some party trick, it’s almost like a secret language, one that even our ancient ancestors used to their advantage. Some people make a living out of studying arching eyebrows, Penny Spikins is one of them. Dr. Spikins is a senior lecturer in the archeology of human origin at the University of York. Dr. Spikins, welcome to the show.

PENNY SPIKINS: Hello.

IRA FLATOw: So what did our ancient ancestors eyebrows look like?

PENNY SPIKINS: Well actually, the story about eyebrows goes back a little bit before people had eyebrows like our own. Because if you go back like, 200, 300,000 years ago, and you see some early human, actually, their face looks really different from ours because they had really huge brow ridges, a big bony protrusion that went above their eye. And for a long time, we’ve not known what that’s for. So, we’ve really not understood what’s happening in people’s eyes that far back in time.

There’s been an idea, it’s to do with it may be buttressing the face, or supporting chewing muscles, all of those things. So what we did in our research, Ricardo Gadino, one of the researchers here, made a model of the carboys skull. That’s an archaic human with these huge supraorbital ridges, and tried to test out what it could be for. And what was really interesting, was that there was no good functional explanation. Doesn’t help with chewing, if you had that or you didn’t have that there, made no difference to the way in which your face was working, really, in which those muscles in the jaw was working.

That was really interesting, because that suggests that this bony ridge had a kind of social function. And of course, if we look at other primates we can see similar bony ridges. You imagine a chimpanzee, you know, you can see chimpanzees have got a bony ridge. And in fact some primates like mandrels have a huge bony extension down the nose. And in these primates, these kind of gestures of intimidation. You know, these are big scary things permanently there. Paula Higgins and our groups compare them to antlers, you know, there’s nothing to do with social competition that is just permanently there above the eyes.

But of course, this big lump that the effects of having this big lump and a receding forehead, is that there’s not that much movement can be made up of your eyes. This is making a pretty obvious signal. It’s a blunt signal to others, you know. We know chimps can pull their skin over the lump above their eyes, but it’s a yes or no kind of, like, signal.

So, as we go through time, as we get towards our own species, this bony lump disappears, and instead we have vertical foreheads. We don’t have a brow ridge, and we have eyebrows that move around. And that’s interesting, because from being species that can’t make much subtle signs above our eyes, we become a species that can make all these subtle signs. As you were saying, sympathy, a gesture of recognition. One raised eyebrow, all though I have to say Ira, one of the disappointing things is that I can’t raise one of my eyebrows. Dammit.

IRA FLATOw: Well, I was going to ask I was going to ask you about that. Does that mean that if you can do that, you have an advantage over, in expression wise, over someone who cannot?

PENNY SPIKINS: I don’t know. I think I can just do a little bit of questioning with by raising both eyebrows pretty well. So I think I’ve probably got that- I get the same, I get the same thing across, even though I can’t quite do it with one eyebrow. So I don’t think we can really apply it, between us. The difference is us, as modern humans, compared to the species in the past. And the interesting thing that tells us, I think, about changing pressures on what was important about social relationships. Trying to, kind of, what we do with our eyebrows has a lot to do with friendly things, friendly gestures, really subtle friendly gestures, and a really subtle social justice. Like you said about raising your eyebrows, you know, I was saying, you know, you sit in a meeting, and you say something, and you think you’re on the right track. And then you notice that a few people have raised their eyebrows and you think, “OK, maybe I’ll draw that back in a little bit.” It’s so subtle, isn’t it?

IRA FLATOw: It is. But why did we get two eyebrows, and not one monobrow that goes across?

PENNY SPIKINS: I don’t think we know about that. We only know about what makes eyebrows movable, you know. It’s about all the muscle movements allowing them to move, you know. I think some people do have one eyebrow that goes across, but I think that’s all just part of like the glorious thing about the differences between us.

IRA FLATOw: Why do you think eyebrows got to be the most expressive feature? Why not cheekbones, or jetting jaws, is something important about that space above the eye? I guess you’re saying it’s because that’s where the bony part was and that’s what people notice first.

PENNY SPIKINS: I guess. I mean our eyes are very expressive. All the movements around our eyes are expressive, but it’s just that bit above the eye is changing through time, and that’s why we’re really interested in it. But can I tell you something about dogs? I think you’re going to find this interesting. You talk about puppies and maggots a while before but this is something completely different. OK, so when dogs became domesticated, they also had changes in their face. But the other thing that happened is they got more waggy tails. And in a way that’s quite similar, because they found a means a, you know, evolutionarily, there was a means of showing friendliness at a distance, to other dogs, to humans, because your tail’s really waggy. Now we don’t have tails. We couldn’t have waggy tails. But we could have, these subtle signals in eyebrows that say, “hey I’m not scary”. You know, I don’t have a big brow ridge, I’m not trying to be intimidating. I’m not going for social dominance, I want to be friends.

IRA FLATOw: So when did smiling become important, as a signal cue to people? Do you think the eyebrow is more important than a smile?

PENNY SPIKINS: I have, I don’t know. And these are wonderful, wonderful questions which we should think about, but it’s very hard to say. I mean, we can look in our research because we have a bridge that we can measure, and we can model, you know, and we have a lack of a brow ridge. But, it’s very hard to get at those kind of, smiling muscles, because you could have them but not use them, you know?

IRA FLATOw: Yeah, so if you have some sort of interference with the muscles in your forehead, that you’re not able to move your eyebrows as well as someone else, you’re not conveying messages as easily.

PENNY SPIKINS: Oh, that’s so interesting, too. You know, there’s been some studies on people who had Botox on their forehead. They’re not making the messages, but what’s more interesting still, is they’re less empathy empathetic to other people. Because without being able to make those little messages, imagine sympathy, you don’t really feel the same, yourself, in response to somebody else’s feelings. So you’re actually feeling less empathy towards someone else, which is really interesting because that’s just with numbing those muscles in the forehead.

IRA FLATOw: So are our eyebrows then, vestiges of our ancient ancestors that we learned how to make better use of?

PENNY SPIKINS: We don’t know whether, on top of the bone images that would have existed prior to our species, there could have been bits of fluff. We can’t tell, there’s nothing preserved. But, of course, if we look at other primates, they certainly don’t have that, you know. The brow ridge, you know, is actually bare. So it’s much more likely. I mean, if I had to bet on it, I’d say they didn’t have eyebrows. But unless we actually find somebody completely preserved that shows us we didn’t, we can never say for sure. But, most plausibly, they didn’t have eyebrows. And once the face shape changed, then those eyebrows came in, and the movability of the eyebrows came in.

IRA FLATOw: So, why did we develop these modern face shapes, the modern foreheads?

PENNY SPIKINS: Well, the question about- there was several things going on. OK, so one of the things going on, is changes, all sorts of changes in our hormones that we think are to do with the need to get on better with others. So we see a flattening of the face. There’s some changes to do with, perhaps, chewing different foods as well. But if we look at the wider social picture, what’s really interesting is only after faces of change, and we’ve got these eyebrows, do we see connections between different groups. And they’re really important for human evolution because we see gifts moving along long distances, people move into new territories, and we see different group compositions.

IRA FLATOw: Yeah, now if eyebrows are such an important tool for social communications, why do we pluck them out?

PENNY SPIKINS: Again, now you know this is what got Paul, one of the people who worked on the project, started on this. Because he was actually pondering his daughter’s plucking their eyebrows and thinking, “What is this with eyebrows? Why are eyebrows so important?” And that’s how we started to look at eyebrows. But as to why we pluck them out, that’s just us, isn’t it, not humanity as a whole. I think we’re probably a bit odd, in time and space, aren’t we? Our society is for doing the eyebrow plucking thing. So, I don’t know whether there’s a good evolutionary explanation for that. We do a lot of odd stuff, and plucking our eyebrows is just, probably just one of them.

IRA FLATOw: That’s sort of a fashion thing?

PENNY SPIKINS: Yeah.

IRA FLATOw: So what do you want to know more, about eyebrows, that you don’t know? What kind of questions still remain?

PENNY SPIKINS: You know, what interests me is that bigger picture about why and how humans become more tolerant of people that they don’t know, and able to forge relationships based on trust with people that maybe live a long way away, that they don’t meet very often. So, that’s a big change. If we look at the rest of primates, they don’t have relationships with other groups, do they? They don’t form relationships with other groups, and yet we all do that. So I’m interested in that, what exactly is happening around those changes, of which eyebrows are just one part that allow us to kind of work with other people.

IRA FLATOw: So, if I want to make a good impression on a stranger, should I use my eyebrows to do something?

PENNY SPIKINS: I guess it depends what you are thinking of doing with your eyebrows, Ira. Like, you know, a great big frown, I probably wouldn’t recommend that. That might not go down so well.

IRA FLATOw: Well, you know, Groucho Marx made good use of his eyebrows.

PENNY SPIKINS: And you know who else made good use his eyebrows, have you seen Charles Darwin’s eyebrows?

IRA FLATOw: Not recently.

PENNY SPIKINS: He has really impressive eyebrows.

IRA FLATOw: Are they missing? That’s the answer to that question.

PENNY SPIKINS: No, no they’re not missing. They’re not missing. But if you look on the web, he had some pretty impressive eyebrows. Which is interesting, because he was one of the first people that noticed how important the eyebrows were in, kind of, facial expressions.

IRA FLATOw: Is that right?

PENNY SPIKINS: Yeah.

IRA FLATOw: Did he write about that? I mean he’s published?

PENNY SPIKINS: He did. That was in 1872, Expressions of Emotion in Man and Animals. So, that’s the first big work that looks at expressions of emotions, all that time ago. And you wonder if he looked in the mirror and thought, “Hmm, eyebrows”.

IRA FLATOw: Well, they’re some birds that have eyebrows.

PENNY SPIKINS: Really?

IRA FLATOw: Yeah, I’ve seen some birds with, sort of, big fluffy feathers up there that looks sort of like eyebrows.

PENNY SPIKINS: There’s a study on dogs in shelters, and some dogs can lift one, it’s not quite an eyebrow but one area of their eye looks like an eyebrow. And they’re the ones that are most likely to get re-homed, because we think they look so cute.

IRA FLATOw: And there you have it, that’s the secret. It’s the secret of eyebrows looking cute and communication. Thank you, Penny. Very interesting.

PENNY SPIKINS: Thank you, Ira. Pleasure.

IRA FLATOw: You’re welcome. Penny Spikins is a senior lecturer in the archeology of human origin, at the University of York.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.