The Woman Who Linked The Web In A ‘Microcosm’

Hypertext links one thing to another on the Internet. But, in 1989, computer scientist Wendy Hall invented a specialized linkbase to build a more connected web.

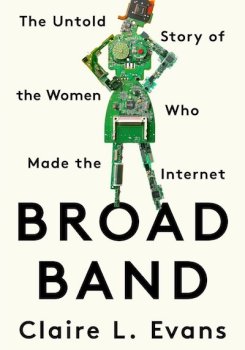

Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

The following is an excerpt from Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet by Claire L. Evans.

Microcosm’s core innovation was the way it treated links. Where the Web focuses on connecting documents across a network, Wendy Hall was more interested in the nature of those connections, how discrete ideas linked together, and why—what we would today call “metadata.” Rather than embedding links in documents, as the Web embeds links inits pages, Microcosm kept links separated, in a database meant to be regularly updated and maintained. This “linkbase” communicated with documents without leaving a mark on any underlying document, making a link in Microcosm a kind of flexible information overlay, rather than a structural change to the material.

To use one of Wendy’s examples, say I’m browsing the [late Lord] Mountbatten archive [one of the first information sets her system] using her system, Microcosm, circa 1989.* I’m interested in Mountbatten’s career in India, a two-year period during which he oversaw the country’s transition from colonial rule to independent statehood. This history has its recurring characters: his field marshal, the leader of the Indian National Congress, Jawaharlal Nehru, and of course, Mahatma Gandhi, whose name is everywhere in the source material.

Say also that within the Microcosm linkbase, an instance of the name “Mahatma Gandhi” has been linked to some multimedia information—a video, perhaps, of a Gandhi speech. Because of the nature of Microcosm links, that connection isn’t isolated to a single, underlined, hyperlink-blue instance of those words. Rather, it’s connected to the idea of Gandhi, following the man wherever his name may turn up, across every document in the system. Further, if I were to bring a new document into Microcosm, the system would automatically identify any words corresponding to links in the linkbase and update it accordingly. Imagine the analog on the Web we know today: for every name, for every idea, for every linkable thing, a single repository of supplementary material, updated by everyone in the world, filtered based on parameters determined by the user.

Links in Microcosm could be tailored to the user’s knowledge level and could point to several places in the linkbase at once. Microcosm was even able to dig up new links on the fly by running simple text searches on all the material in the system—a prescient design that anticipated the importance of search in navigating information. This “generic” linking, in concert with linkbases, created a system that could adapt to its users while presenting them with more opportunities to learn. “Links in themselves are a valuable store of knowledge,” Wendy explained. “If this knowledge is bound too tightly to the documents, then it cannot be applied to new data.” Which is to say: where one instance of a connection might be interesting, multiple instances, expressed laterally, look more like truth. By making space for this generic knowledge, Wendy’s system placed value on the association between documents, rather than on the documents themselves. To hypertext’s small but active community of scholars, this is what the field was all about.

In the years between 1984 and 1991, a flurry of hypertext systems like Microcosm emerged from universities and from research labs at technology companies like Apple, IBM, Xerox, Symbolics, and Sun Micro systems. Each suggested different linking conventions, spatial associations, and levels of micro- and meta- precision over contained corpora of information. If this sounds dry, remember that managing, navigating, and optimizing information is a central pursuit of modern life—we do it fifty times a day before breakfast—and that each one of these systems had the potential to become as important to us as the Web is today.

The young discipline of hypertext was heavily populated with women. Nearly every major team building hypertext systems had women in senior positions, if not at the helm. At Brown University, several women, including Nicole Yankelovich and Karen Catlin, worked on the development of Intermedia, a visionary hypertext system that connected five distinct applications into one “scholar’s workstation,” and invented, in the process, the “anchor link.” Intermedia inspired Apple, which had partially funded the project, to integrate hypermedia concepts into its operating systems. Amy Pearl, from Sun Microsystems, developed Sun’s Link Service, an open hypertext system; JanetWalker at Symbolics single-handedly created the Symbolics Document Examiner, the first system to incorporate bookmarks, an idea that eventually made its way into modern Web browsers.

For women interested in the nature and future of computers, hypertext was far more collegial than other areas of computer science, which was at that time seeing a rapid decline in female participation at both the academic and professional level. The reasons for this aren’t cut-and-dried, but they reflect some of the same tendencies at play over previous generations. While “the whole foundation of hypertext is collaborative,”suggests Intermedia’s Nicole Yankelovich, and “collaborative work appeals to women,” hypertext was also, like programming before it, an entirely new field, a clean slate upon which women could mark their place. Further, hypertext was open to scholars from outside computer science departments, who emerged from such wide-ranging disciplines as interface design and sociology. What these people shared was a humanistic, user-driven approach. To them, the final product wasn’t always software: it was the effect software had on people.

*Clarification was added, per author.

Excerpted from Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet by Claire L. Evans, in agreement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © Claire L. Evans, 2018.

Claire L. Evans is the author of Broad Band: The Women Who Made The Internet (Portfolio, 2018).