High School Science Projects Go High Tech

16:50 minutes

What were you doing when you were in high school? Were you investigating how supernovae explode? Designing 3D-printed nano-devices that can absorb bacterial toxins? Writing algorithms to detect gender bias in the news? Those are just a few of the ambitious projects more than 1,800 high school science whizzes submitted to the Regeneron Science Talent Search, a competition founded by the Society for Science and the Public. One thing is for sure: If these students are the future, the future is looking bright.

[Five tips to help young inventors patent their inventions.]

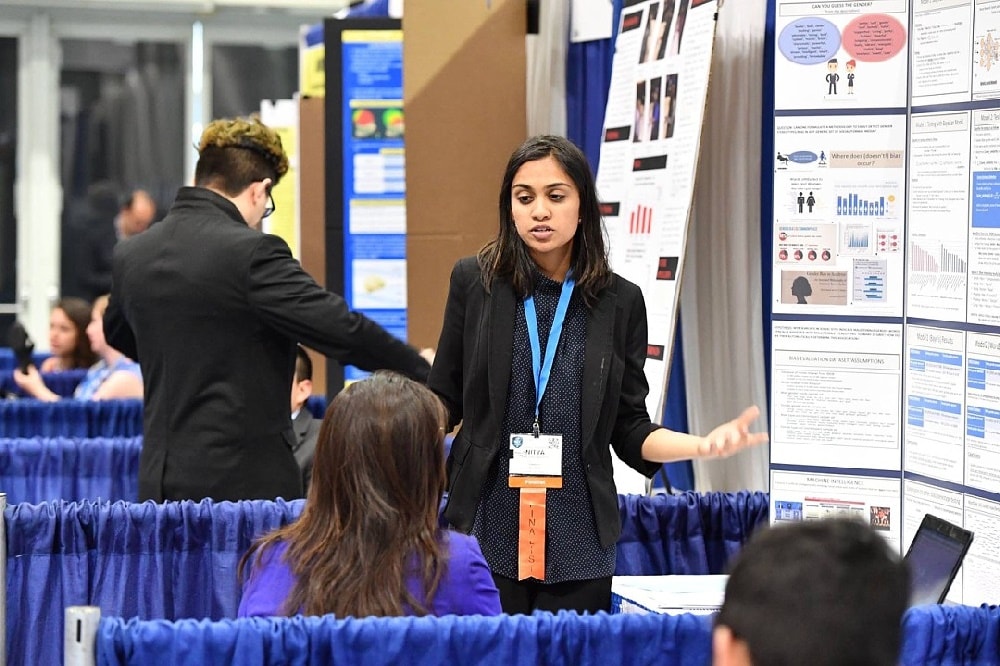

This week and next, 40 finalists are presenting their projects in Washington, D.C. to determine the top winner, who will be announced on March 14. Among the finalists is Haniya Shareef of Lincoln Park Academy in Port St. Lucie, Florida, who used a parasitic fungi to develop a new weed-killing cocktail, which might help control invasive purple nutsedge. Finalist Nitya Parthasarathy from Northwood High School in Irvine, California was compelled to create an algorithm that detects and measures gender bias in social media after experiencing gender bias firsthand in her family and an internship. In this segment, Shareef and Parthasarathy join Ira to discuss their projects and their scientific passions.

SciFri continued the conversation with two of the participants. Learn more about them and their projects below!

Northwood High School, Irvine, California

Briefly, what is your project?

Gender bias is basically the surrounding topic of my project. The first thing I looked at was what is the correlation between the word “he” and the word “strong” [in online movie reviews]… We’ll associate males with words like “strong” or “smart” and females with “kind” or “caring…” From there I moved on to algorithmic analysis… to look at the word “strong” but take out the word “he.” Could the computer guess whether “he” or “she” should go in there?… Another algorithm I used allows you to output a similar word if you input two words. So if I put “gentle” and “woman” in the program, it’ll come out with “naive.” But if I put “gentle” plus “man,” it comes out “compassionate.”

The goal for me was just to see if the algorithms could detect [and capture] the bias…, and they were able to with a significantly high success rate… From there I created a program so that anyone can put potentially any document inside my program and it will give you a bias score.

How did you first become interested in science?

Science has always been a passion of mine. When I look outside, I think about the way the world works and that always fascinates me. In terms of engineering and technology, my dad is a computer engineer and so I’ve always been exposed by going to his work and him bringing home computer chips after the end of the day. And so I think that was the natural inclination for me because it’s something that I’ve always been exposed to.

[What are the impacts of social media algorithms? Use this activity with students.]

Why did you decide to look into this question?

Gender bias is something I’ve experienced my entire life. One of the events that really got me started on the project was when my brother, my dad, and I were driving to get boba [a bubble tea drink] and my brother started crying about how badly he wanted to get it right now. My dad said, “Stop crying like a girl.” And for some reason that day I just took severe offense to the statement. It’s not something that I haven’t heard before, but it just made me realize how often we associate negative characteristics with women and really got me questioning as to why we do that.

There was an interview given by Meryl Streep around the same time where she was talking about how if you look on Rotten Tomatoes or movie aggregators of any sort, it is skewed towards the male population… There are so many more male reviewers than female reviewers, that it is biased towards the male population and what their interests are. And that really got me started on analyzing movie reviews and that led me into my project.

What was one surprising thing you learned during the experiment?

It’s not necessarily related to my project, but the response has been wonderful and surprising. I would like to say that the results that I got and the fact that there were so many biases were surprising, but it’s really not. I think what really took me back is how much support people have [for this project] and how people are really willing to try to make a change.

After presenting my project, I’ve had so many people ask me, “So what steps do you think we need to take to fix this bias?” I think this is a huge problem. This is coming from everyone, from teenagers to the adults judging my project. So I think when a community comes together, that’s when you know it’s really, really wonderful.

[The Hyperloop: From pipe dream to possible.]

If you could have dinner with any scientist (living or dead) who would it be and why?

I’m inclined to say Elon Musk. I don’t know if that’s a stereotypical answer, but as a child my dad used to tell me stories about Elon Musk. The idea of being at the forefront of both technology and business and innovation is something that’s really inspiring to me. And I know that he has some really polarizing views on artificial intelligence. I’d love to talk him about that, and I just love hearing about what people think about the future of AI and technology.

Lincoln Park Academy, Port St. Lucie, Florida

Briefly, what is your project?

My project was focusing on combating an invasive weed that’s becoming a huge problem around the world. It’s a common one called purple nutsedge… Nutsedge is definitely a big problem not only in gardens, but also commercially and they have a really big impact on agriculture output, especially here in Florida. I’ve found a way to combat their growth and destroy them in a way that’s really eco-friendly… I took a biological organism [a rust fungi] and utilized its natural capabilities to attack this weed.

How did you first become interested in science?

I started science research in the sixth grade, simply because I had to get volunteer hours. My older classmates told me there was a lab close by that I could get volunteer hours at and I simply went in with this, but over time, my mentor—the person who let me volunteer there—he would explain to me why I was doing the certain things I was doing over time. I asked him if I could do a project with him, and as the years went on, my curiosity just increased and increased until I went on to the United States Department of Agriculture where I work now. I think it was just being exposed to the environment that kind of made me love it. I started off at such a low level, of simply washing dishes and cleaning the petri dishes, and eventually grew to love it and continued on in complexity.

[These science students learn to think on their feet.]

Why did you decide to look into this question for your project?

I’ve been working with biological controls since the sixth grade. From sixth grade to ninth grade, I worked at a very basic level and then when I went on to the USDA, I started working on fungi and fungi as a mechanism of biological control. Particularly what intrigued me about this is when my mentor told me about this population [of purple nutsedge] in Florida, and being able to identify a new host-pathogen interaction and come up with something that could potentially be much more everlasting than a typical biological control. I think that’s really what got me involved—the opportunity that I was provided with, being in the right place at the right moment, and being interested in that thing that was presented to me in such a lucky manner.

What was one surprising thing you learned during the experiment?

I think one of the most surprising things that I learned was patience, especially with science and especially with different mechanisms within science. I hadn’t been exposed to such in-depth research before, and I didn’t realize that something as simple as DNA extraction or identification of DNA takes time. I never understood how much time it actually takes scientists to do these things on a daily basis. It takes hours, and I don’t think people realize that. I think that was something that really surprised me was just the amount of time scientists and people who are so concerned about the environment need to make the discoveries that they make.

[Bioengineer Manu Prakash explores scientific simplicity by design.]

If you could have dinner with any scientist (living or dead) who would it be and why?

Manu Prakash’s lab is probably one of my favorites. He has a lab based in Stanford and he creates things with a focus of applicability and practical applications, which I think is really amazing. I would love to speak with him and see how he comes up with these unique projects that could be applied in several countries. He created a foldscope, which is [very affordable] and it allows several countries’ students to see microscopic organisms which I think was super amazing. I saw him talk at the International Science Fair, and ever since then I was just starstruck. He’s really taken science to a place that’s so practical, to a place that hasn’t really been seen before.

These interviews have been edited for space and clarity.

Nitya Parthasarathy is a high school senior at Northwood High School in Irvine, California.

Haniya Shareef is a high school senior at Lincoln Park Academy in Port St. Lucie, Florida.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Back in high school, did you build a project for the science fair? Mine was a punch card reader. If you’re of a certain age, you’ll know what I’m talking about. If not, there. There are a lot of other ideas that might impress science fair judges. Let me give you a few. How about analyzing the chemical makeup of stars to discover just how exactly supernovas explode? Or why not 3D print a nanoscale device to suck up toxins from antibiotic resistant bacteria? Those are two real examples of projects in this year’s Regeneron Science Talent Search, a science competition founded and produced by Society for Science & the Public.

There are more than 1,800 students from high schools around the country that entered and now just 40 brainy finalists remain. They’re in Washington, DC for the final judging now, and we’ve got a couple of them on the line today. Let me share them with you.

My next guest is one of the finalists. Her project, an algorithm that can sniff out gender bias in movie reviews and news articles. Nitya Parthasarathy is a senior at Northwood High School in Irvine, California. She joins us by Skype. Welcome to Science Friday, Nitya.

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Hi. Happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Now you designed an algorithm to detect gender bias in text to look at the relationships of certain words like “strong” or “smart” with either men or women. Tell us about that.

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Sure. So oftentimes in societies we’ll see males referred to as “strong” or “smart” and females referred to as “kind” or “caring,” and I wanted to examine this. And the first way I did that is through statistical analysis. And I found that we often do associate males and females with those stereotypical adjectives, but I also noticed that was really interesting is that we associate males with some female stereotypical adjectives. So not only will we call them “strong” or “smart,” but we’ll also call them “kind” or “caring.”

And from here I moved on to algorithmic analysis to see if I could create an algorithm to detect these biases. So there’s the sentence, “He is strong,” and I took out the word “he.” Could the computer guess whether he or she should go in there? And so now I have a program that allows anyone to put any document they have into my program and it’ll give you a bias score, basically telling you how biased your document is.

IRA FLATOW: Can you expand this thing into other kinds of biases, like racial bias, political bias?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Yes, that’s one of the great things about my project is that it so easily extends to different types of biases. Like I mentioned in the sentence, “He is strong,” if I replace the word that I was looking for which is he or she with racial pronouns like African-American or any term like that I could easily detected the biases that we use to describe different races. I can do the same thing with age, even political biases that we have.

IRA FLATOW: Now I know you use neural networks and things like that for this project. How did you learn to use all of these computer programming tools?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: So for me, I think this is all inspired by my project. I started off realizing that there’s a problem with gender bias and I wanted to do something about it so I came up with this project. And I wanted to objectively measure bias in society, and I knew that to do that I needed to use algorithms. And so really the way that I learned it was looking online to research and read papers. And my passion for analyzing bias really carried me through all that literature and being able to understand what was happening. And I kept reading online about the best algorithms to use, I read up on courseware from Stanford and MIT where they described how neural networks work and learned through that.

And right now I’m taking AP Computer Science to develop a more fundamental knowledge of computer science as a whole. But really my project and my understanding of neural networks just stemmed from an interest to analyze my project, and from there I really learned neural networks.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re being modest. What you basically did was teach yourself everything.

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Kind of, yeah. I think that for anyone if they’re really interested in something, if you find a topic and explore through basically working backwards. You have a topic and you want to figure out how something works and you work backwards. I think that’s the best way to learn.

IRA FLATOW: You say you were inspired to pursue this as a project. Was there an event in your life that was key in your inspiration?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Yeah. I think there are two events specifically that really started off my project. I’ve experienced bias throughout my life. One of the key experiences I had was in eighth grade, I decided that I wanted to be a doctor because I just really want to help people and immediately people started telling me, oh, you want to go to medical school? Don’t you want have children? Don’t you want to have a family? Like the two were exclusive. I immediately stopped wanting to be a doctor because people expected me to have my whole future life plan out when I was in eighth grade. And so that bias totally carried through my life.

And there was a special aha moment when I really began my project. My brother, my dad, and I were driving to get food one day, and my brother started to cry asking for a boba, or bubble tea on the east coast. It’s a type of drink. And my brother is obsessed with this drink and he started to cry and my dad said, “Stop crying like a girl.” And for some reason that day I just took severe offense to the statement. It’s something that you hear all the time. You run like a girl. Stop crying like a girl. But I was so sick of women always being associated with this weaker terms. And I really wanted to examine to see if this was something that was just in my community, is this is a societal problem, and what can I do to change that? And that’s really what started my project.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That’s really interesting. So you really have a passion for studying and doing something.

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Yeah. I mean especially today we’ve seen so many women speak out. I think whenever you see a problem in society, or at least for me, there’s always an inclination to somehow fix that. And I’m really glad that through my project I’ve been able to take a step towards fixing gender bias. And so yeah, I’ve always had a passion for helping other people, and through this project I’ve really realized that computer science is the way that you can truly help people.

IRA FLATOW: So do you think that teenagers should become very involved in speaking out when they see something they don’t agree with?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: I do think so. I think a lot of people think that teenagers don’t really know what they’re talking about, but we have a totally different perspective. We have a fresh set of eyes. And sure, sometimes we can be naive and idealistic about the world, but I also think that’s great. The fact that we can hope for something that might not be practical, but the longer and the more we strive to achieve that type of idealism, I think we’re going to reach as close as we can to, maybe not perfection, because perfection is boring, but some sort of equality in the world, or just a general sense of improvement. I think that teenagers really are inspired to change the world, and every issue that they think the world needs to solve, especially now, they’re taking it into their own hands. And I think that is something that is really admirable and should be encouraged.

IRA FLATOW: And you see computers as a way of taking that power.

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Yes. I think that technology is complicated but it’s so interesting and it’s really the future of the world. And computer science especially, and computers in general are really the new wave in being able to– I mean there’s so much you can do with it. You can relate it to biology, to fashion, if you wanted. So there’s so much to discover and I think computers and computer science is the perfect way to do so.

IRA FLATOW: I know that some technologists like Elon Musk whom I understand you admire are worried about the implications of artificial intelligence. What’s your take on the future of AI? Should we be worried about it?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: So I’m still developing my view, and that’s why I respect Elon Musk so much because there are definitely negatives to AI. And I think a lot of people think that AI should be a robot and should be a tool that we use rather than something that’s starting to take over. And I totally understand that aspect. But I think there’s so much merit to looking at AI as modeling the human brain, and trying to see what we can achieve. Can we achieve a neural network or any form of artificial intelligence that can process things or information like the human brain? And I think there’s so much that we can discover through that.

And I agree that there are some really dangerous possibilities, and we’ve already kind of seen that peak through. And AI can definitely lead to some dangerous possibilities, but I think that we’d be doing a disservice by not examining and trying to push forward science. I think when we look back at just science in general when people who really worried that science would change their perspective of the way the way they thought the world acted, and then we see now how science has led to so many new discoveries, I think that if we try to inhibit what we can do with AI just because we’re afraid of the possibilities– and I know that they are dangerous and know there should be limits, but if we try to inhibit that too much I think we’re doing ourselves a disservice.

IRA FLATOW: I want to bring on another finalist. She investigated invasive species and how to get rid of them using biological controls. I’m going to let her explain it. Haniya Shareef is a high school senior at Lincoln Park Academy in Port St. Lucie, Florida. She joins us from NPR. Welcome to Science Friday.

HANIYA SHAREEF: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

IRA FLATOW: We’re very happy to have you. Tell us about this new type of weed killer. First you had to go out into the natural world and hunt for the weed’s natural enemies? Tell us about this.

HANIYA SHAREEF: Yeah. So there is a weed, particularly called purple nutsedge, and it’s become a huge problem not only in Florida but around the world. And basically my discovery was by chance.

My mentor went onto a farm and she saw that this particular nutsedge was being attacked by a rust fungi. However, this nutsedge had never been seen being attacked by this fungi before. So we brought the fungi into the lab and we identified it and we found a completely new association, as in this fungi just never attacked this plant before.

What I did is I took the fungi and I increased its efficacy. So basically what I did is I added different solutions to the fungi that basically make it produce more disease on the plant therefore killing the plant, and therefore being really influential in the agricultural industry and deterring this weed not only in our gardens but also just in corporate scale productions.

IRA FLATOW: You know, history is filled with unintended consequences.

HANIYA SHAREEF: Yeah, for sure.

IRA FLATOW: You know where I’m going with this, right? Could there be unintended consequences to spraying this fungus around?

HANIYA SHAREEF: Yeah. So the biggest thing that separates my project from a typical biological control or a typical experiment where you release an organism into a new environment is that this fungus has already been discovered in the natural environment, so it already naturally attacks this plant. So all I’m really doing is I found this fungus which hasn’t been found before attacking this plant, but it actually attacks it. And I brought it in and it only increased its efficacy. So it’s already it’s already present in the environment. And it’s already doing substantial harm to the nutsedge population, and I only basically increase the amount of harm that it does through using plant based volatile. So the volatiles are also not chemically based. So they’re not bad for the environment in those kind of aspects.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking with some of the finalists in the Regeneron Science Talent Search. With me is Haniya Shareef talking about her new fungus that she’s hoping to keep invasive species from taking over.

For other young people listening today who are interested in science but maybe need a little advice on how to get where you are today, give us an idea of what your path, your trajectory, the thing that got you into science?

HANIYA SHAREEF: Yeah so for me I live in a very small town. I go to a very small public school that doesn’t have as many opportunities as a typical public school does or a typical private school does. So for me, I think the biggest advice that I would give two different scientists is to take every opportunity you can possibly have. If there’s something as small as working in a lab and washing dishes, you never know how far that can take you.

For me in particular, that’s how I started. I started working in a local lab, a very small lab, and I washed dishes and I water plants. And over time I just saw the implications of what these scientists were doing and I became more interested in science in general. So just take every opportunity you possibly can, even if it’s the smallest thing, because you never know where it can potentially take you in the future.

IRA FLATOW: What was the most surprising thing that you learned during your travels in this experiment?

HANIYA SHAREEF: So I think the most surprising thing I’ve learned is patience. Typically when we see or hear about a scientific development on the radio or on a television, we don’t realize how much time it takes for scientists to really come out with something effective. Something as simple as DNA extraction or something as simple as DNA identification takes weeks, if not hours and hours. And that’s such a small segment of the whole project. And I think for me as a scientist it was really surprising to understand the implication that time has on science in general.

IRA FLATOW: Nitya Parthasarathy, what is your advice to people, other people who might take your path?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: I think that just find something that you’re really passionate about and explore it and don’t let anyone else tell you otherwise. That’s something that I myself have been culprit to. When someone discourages you, or discouraged me I easily swayed and moved on to something else. But if you’re really passionate about something I think you should go for it, especially if that something has real merit and could change society, really push forward no matter what anyone else says. Because true change happens despite the resistance that you might have.

IRA FLATOW: Do both of you find comfort in meeting other scientists your age and with your passions?

HANIYA SHAREEF: Yeah. So for me, I think that–

IRA FLATOW: No, go ahead Haniya.

HANIYA SHAREEF: So for me, I think that the most amazing thing coming to Regeneron is that you see students from all around the nation that are just as passionate about something as you are. And sometimes they’re more knowledgeable than you in certain aspects, and you just learn so much from them. And I think that’s the biggest thing that I’ve learned from Regeneron and STS in general.

IRA FLATOW: Nitya, you too?

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: I agree. I think that science, especially today, is so interdisciplinary. And right now we all are very specialized into our own field. And being able to talk to people from different areas and see where our research converges, where they’re different is really interesting.

And being able to talk to these people, and also the response. When you talk about your project for so long, so many people get bored, but when you’re talking to these top 40 finalists they’re so enthralled in what you did. No matter what type of project, whether that be math, or computer science, or biology, and that’s really been wonderful.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I want to wish both of you good luck among the 40 finalists. Nitya Parthasarathy, senior at Northwood High School in Irvine and Haniya Shareef high school senior at Lincoln Park Academy in Port St. Lucie, Florida. Good luck to all the finalists in the Regeneron Science Talent Search. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

HANIYA SHAREEF: Thank you so much.

NITYA PARTHASARATHY: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Congratulations for getting this far.

Our digital producer Lauren Young has put together beautiful Q&As with both Haniya and Nitya. It’s up on our website where you can read more about their projects. And you can find out more about how they got into science. They are all up on ScienceFriday.com/HighSchoolScience. ScienceFriday.com/HighSchoolScience.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.