Jellyfish, The Misunderstood Genius Of The Sea

23:52 minutes

This story has been resurfaced as part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

This story has been resurfaced as part of Oceans Month, where we explore the science throughout the world’s oceans and meet the people who study them. Want to dive in with us? Find all of our stories here.

Jellyfish have an image problem. They are seen as some of the ocean’s most destructive and harmful creatures. Tourists are stung, fishing nets are clogged, and intake pipes are stuffed. Jellyfish can be problematic for many industries and cause catastrophic losses. They also seem to be thriving in a warmer, more acidic ocean impacted by climate change.

That is one story that is being told about jellyfish. Juli Berwald’s Spineless (Riverhead Books, 2017) is another. She reveals that even scientists are divided over the causes of the recent changes of jellyfish populations and how much humans are to blame for it.

[Read an excerpt from Juli Berwald’s book “Spineless.”]

At the same time, she celebrates jellyfish for their remarkable abilities and gifts they’ve given the scientific community. She joins Ira and Dr. Lucas Brotz, a post-doctoral researcher at the Institute for Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia to discuss perception versus reality when it comes to the jellyfish.

Juli Berwald is the author of Spineless (Riverhead Books, 2017). She’s based in Austin, Texas.

Lucas Brotz is a post-doctoral researcher in the Institute for Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. I never saw the jellyfish that stung me. I was snorkeling quietly and then came the sharp pain in my shoulder and the welt that lasted a week. So when I now see a jellyfish, either as gooey blob washed up on the beach, or swimming impulsively in an aquarium, I’m thinking, be careful. Yeah there’s still a bit of fear there in me.

And I’m not alone. If you follow science news, maybe you’ve read the headlines like, the animal without a brain is taking over the oceans, or jellyfish or taking over the seas and it might be too late to stop them. Needless to say, jellyfish are badly in need of some image repair. And my next guest, well, she’s up to the challenge. In her new book, Spineless, science writer Juli Berwald has compiled some of the most fascinating and wonderful facts about jellyfish. Who knew? Like how it can launch its stinging cell with an acceleration of five million times the force of gravity! Five million times the force of gravity makes the mantis shrimp look like slow motion.

And she explains why determining whether jellyfish are taking over the oceans is a lot more complicated than some of those dramatic headlines make it sound. In fact, it might not even matter. She joins me now. Juli Berwald. Science writer and author of the new book, Spineless. Welcome to Science Friday.

JULI BERWALD: It is a privilege to be here. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re very welcome. Also joining us to discuss jellyfish science is Lucas Brotz, a post-doctoral researcher in the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Brotz.

LUCAS BROTZ: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: All right, Juli. Tell us. I read the book. Fascinating book. It is everything you ever wanted to know about jellyfish, but it’s also your personal journey, is it not?

JULI BERWALD: It is. Yeah, it is a mixture.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us why you decided to share it with us.

JULI BERWALD: I really wanted to tell a story where the author wasn’t this mystery person telling you really smart things all the time. And I felt like connecting with my audience was super important to me. It may be just because I like right reading memoir and fiction a lot, but I wanted to make that connection with my reader.

IRA FLATOW: But you also seem to want to debunk what we think about jellyfish.

JULI BERWALD: Well, I wanted to add more nuance to the conversation for sure. Whenever you start looking at something hard it’s always more interesting than where you started before that. And every time I dug into the story of jellyfish, any part of them, I would find these gems. These science stories I really felt like hadn’t been told. And it was so fascinating.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think the media was misrepresenting what we knew about jellyfish, or what you were learning about jellyfish?

JULI BERWALD: Yeah, the headlines blare sometimes. And that’s part of their job is to get people to read the article. And, to tell you the truth, the science community is in a tough spot. Because throughout the 20th century, the way we studied the oceans was by pulling nets and winches and using research vessels with big, strong motors to go through the oceans. And that was a really good thing to do because the ocean is a very big place and we need to know more about it.

But what happened along the way is we biased ourselves away from jellyfish because the things that come up in those nets are durable. They’re hard. They have bones, or shells, or something like that to allow them to come up in those nets. So our understanding of jellyfish for the 20th century is really poor and we can’t get that back.

So then when we started seeing larger blooms in coastal places, it’s easy to say they’re taking over. But once you start digging into the science, again, the nuance is really, really important. And I’m not saying they’re not taking over, because in some places, there’s definitely been a shift where jellyfish dominate ecosystems. But looking at those more local places might be the better way to go about it.

IRA FLATOW: Lucas, I know you were part of a study that had scientists really divided over what jellyfish populations were doing, as Juli talks about, as kind of local. What was the debate over the data in that study?

LUCAS BROTZ: Well certainly there’s a lot of challenges when you try to look at the population dynamics of something like a jellyfish. As Julie mentioned, they’ve historically been ignored both because of the sampling equipment that we use but also because jellyfish populations naturally are highly variable based on the kind of life cycle that they have. So one year they’ll be millions, the next year they’ll be none, the next year will be thousands.

So there’s a lot of noise in the signal and it’s difficult to extract an increase. And so with this paucity of data around the world, at least scientifically we had to start asking, well, should we include anecdotal data? Marine scientists, or lifeguards, or fishers who have been in an area for decades know it really well. And they can attest to say, yes, for sure I’ve seen an increase in jellyfish in my lifetime. But a lot of scientists would reject that type of data if it’s not categorical and data scientifically-driven. There’s some controversy over whether or not you can include these types of anecdotal data.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask our listeners. Do you think jellyfish get a bad rap? What have you always wanted to know about them? Our phone lines are open. 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri.

So what would you have to see then, Lucas, to be convinced that jellyfish are on the rise on the global scale? You say it happens in different places. And we know the oceans are warming and there’s new research showing that that’s more hospitable to jellyfish populations. So what kind of data do you need?

LUCAS BROTZ: Right. So when I’m asked this question, are jellyfish increasing globally, I often respond with, well, what do you mean by a jellyfish? What do you mean by an increase? What do you mean by global? And over what time frame? Because you can define those things in many different ways. There’s no agreed upon definitions for a lot of those things. And so you can come up with different definitions that will lead you to a yes, no, or a maybe.

I think that the major conclusions we took away from our study was it’s definitely not all jellyfish increasing in all places. But we did see a signal, around the globe, that says jellyfish definitely appear to be increasing in more places than they’re decreasing. And so we’re seeing a lot of sustained increases in different places around the world.

And a lot of those places are very disparate from each other. So they don’t appear to be directly connected. And so we’re seeing increases in jellyfish off the coast of Asia, around Europe, off the coast of Africa, even remote places like Hawaii and Antarctica. And so we start to question how many examples do we need before we can say this is a global phenomenon.

IRA FLATOW: I’m fascinated. You glossed over this quickly. But I have to back up. You originally said, what’s the definition of a jellyfish? Are you saying we really don’t have a clear definition of what a jellyfish is?

LUCAS BROTZ: That’s true. Juli covers this a bit in her book and maybe she can speak to that. But these gelatinous organisms that have certain characteristics. Once we dig into the evolution, and the taxonomy, and the phylogeny of these types of different organisms, we realize that many of them are quite distantly related on an evolutionary timescale. So what we consider to be jellyfish might cover three different phyla. And so these distantly-related organisms, lumping them into the same category can be problematic

IRA FLATOW: Juli, tell us why. Now let’s go to the interesting, good news about jellyfish. Why do you love them? What is so different? Tell us why we should love them as much as you do.

JULI BERWALD: So I mentioned that every time I dug in to a different element of jellyfish biology I’d find these fascinating stories. One of my favorites was when I went to go visit these robotic jellyfish scientists in Woods Hole Oceanographic that were studying how jellyfish swim. And they were building robots to try to understand that.

And what they learned was that, you know that little peplum around the edge of the bell, the kind of floppy part that just looks beautiful when they move? It doesn’t need any muscles but it drives the animal forward in the water. And the way it does it is by creating a low pressure system on top of the jellyfish. So a jellyfish actually sucks itself through the water rather than pushes itself through the water.

And once they started looking around the animal kingdom, they found out everything has these. They call them passive margins, these floppy edges that goes through the water. The reason for that is just to use that pull to move forward.

IRA FLATOW: You have to push some place so you can pull somewhere. There’s got to be some sort of pushing someplace. But it’s not there is what you’re saying.

JULI BERWALD: There is pushing. But actually the pulling force is stronger than the pushing force. So it gave them this whole new perspective on how animals move. And it turns out jellyfish are the most efficient movers out there. They use the least amount of energy to go a certain distance for a certain weight.

And then you mentioned the stinging cell, which is this biological treasure. And it’s one of the most sophisticated things I’d ever learned about. It explodes, as you said, at five million times the acceleration of gravity. And that’s the fastest motion in the animal kingdom that anyone has ever discovered.

IRA FLATOW: That is amazing.

JULI BERWALD: It’s even cooler. The trigger. There’s a trigger on that cell. And the trigger is a lot like the hair cells in our ears. So it’s like a clump of cilia that can detect sound or vibrations. And the trigger has to both hear and smell its prey before it will deploy.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That is fascinating stuff. Let me go to the phones because some people now really– We got their interest. Jim in Houston. Welcome to Science Friday.

JIM: Hello, Ira. I was curious. I got stung when I was about 10 years old because I saw this gorgeous, purple little thing in the water; a little pom-pom. And I picked it up and as it slid through my fingers, it stung very much. Like the jellyfish that stung you, what can a jellyfish see or perceive? And with what sort of accuracy? And can it chase prey?

And I was one time working in the Gulf and I saw Portuguese man o’ war as far as the eye could see. It can kill a human being, but does it do it any good? If that jellyfish killed you, could it have held on to you and consume you, or are stings just purely random?

IRA FLATOW: Good question. Juli?

JULI BERWALD: OK, so lots of questions there.

IRA FLATOW: Do they see? Can they hear? How do they pursue their prey?

JULI BERWALD: Yeah. If you are in an aquarium and you’re looking at a jellyfish, in between the scallops– you know how the edge of the bell is scalloped? There’s a little sense organ called a rhopalium, or rhopalia plural.

And so they’ll have eight of them or so. More sometimes. Around the edge of the bell. And each one of those holds eye spots. It has a touch plate which can feel the motion, the current of the water and also smell. Detect chemicals in the water. And it has a balance sensor like a stat assist in there.

So it’s kind of like a little face. And they have many of them around the outside of the bell. And that is how they detect their environment to a large extent. Let’s see, what other questions?

Would they ever eat a human? Lucas? I don’t think so.

LUCAS BROTZ: No, that’s definitely never been documented before.

IRA FLATOW: You are just getting in their way and they’re just stinging you to get out of the way. Or they’re feeling threatened, I guess.

LUCAS BROTZ: Exactly. Jellyfish do kill a lot of humans. It’s hard to say how many because the most dangerous jellyfish, the group of box jellies that can kill people that are located mostly in the South Pacific, are in a lot of countries where you don’t have to file a death certificate. So it’s hard to trace the records back. Of course, someone might just end up drowning as well.

But a few estimates have put it at more than 40 per year which is four or five times the amount of humans that are killed by sharks every year. So it’s certainly significant. But of course, in most of these cases, the jellyfish aren’t actively hunting the humans. They’re doing their own thing and humans just happen to contact them and get stung by their tentacles.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking about jellyfish this hour. A lot of people want to know about them. But let me ask you, Juli. They eat algae, right? What do they eat, plankton?

JULI BERWALD: Yeah. Right. Most of them are carnivorous so they eat zooplankton. They’re after the zooplankton, generally, or fish eggs. But there was a guy who was studying jellyfish in Canada. And he’s tried feeding them different things out of his pantry like oatmeal and peas and they did eat them. Even pine needles.

So I think they will sometimes ingest things that maybe they’re not so specific for, but then they’ll spit them out. But that’s just one. That was a moon jelly. But then there’s other studies that show that jellyfish will be selective. Other species will be selective and only go after a certain kind of zooplankton. So it’s this kind of thing where when we group jellyfish into one big group, we’re missing some of the complexity.

IRA FLATOW: And Lucas, what kind of strategies have people developed for dealing with too many jellyfish in certain parts of the world?

LUCAS BROTZ: There’s been quite a few countermeasures that have been employed to deal with jellyfish populations. In terms of tourism, they have stinger nets that they’ll set up and they’ll basically clear an area of jellyfish and deploy these huge stinger nets. And Juli actually visited a town in Spain where they’ve spent quite a bit of money trying to do this.

Other industries have dealt with jellyfish in various ways. Power plants that are affected by their intake pipes. They have different screens and bubble curtains and all kinds of things that they were trying which aren’t always effective. Certainly the aquaculture industry has been struggling with jellyfish blooms in recent years.

There’s lots of sort of research going on in terms of how they can control jellyfish populations. In terms of using robots to kill them, and drones to locate them, and kill-nets that they drag through the water. But none of them have been really that effective. Really, we’re going to have a lot of difficulty controlling jellyfish populations.

I think part of the immediate-term research that we should be focusing on might be a better prediction model where we can give people an early warning system that say, hey, this might be a bad jellyfish month or jellyfish year. Keep on the lookout. Instead of really spending too much money trying to control their populations.

IRA FLATOW: We have a tweet coming in. It says, are there any health benefits from the parts of jellyfish?

JULI BERWALD: Yeah, there’s a lot of talk going on about that right now. Especially in Italy, there’s a group studying nutraceutical effects like what kind of value jellyfish have. And it looks like they could be involved in wound healing. When jellyfish– they’re often nipped at by fish, and when they heal they don’t actually scar.

And there’s some recent research showing that jellyfish tentacle extract, when it’s applied to human cells, can actually stimulate cell growth and cell migration. So there’s other evidence that jellyfish extract is super-high in antioxidants and some people have found some cancer-fighting abilities. So that’s a huge area of research.

IRA FLATOW: Don’t go away. Can you stay with us a few more minutes? We’re going to take a break and come back. Because we have so many questions from people who are interested in jellyfish. 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri.

Talking with Juli Berwald, author of Spineless. A great book if you want to know anything and everything about jellyfish. Also Lucas Brotz. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re diving into the ocean of jellyfish facts. Yeah, I’ll put it that way. With my guests Juli Berwald, science writer, author of the new book, Spineless. Lucas Brotz of the Institute for Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. We just have a few minutes left.

I’m going to just cycle through a bunch of phone calls. People are asking all kinds of questions. Let them do the asking. I’m going to sit back a little bit. Maureen in Cape Cod. Hi, welcome to Science Friday.

MAUREEN: Hi, Ira. I enjoy your show very much. I too was stung by a jellyfish it felt like an explosion. And it was a sea nettle. I have Parkinson’s disease and I have a tremor in my right arm. And I got stung by the jellyfish on my right shoulder. And it stung really badly for 24 hours. The entire 24 hour period I did not have a tremor. My neurologist thought that was pretty interesting.

IRA FLATOW: There you go. There’s a line of research. Thanks for sharing that, Maureen. So it sort of turned off her Parkinson’s, it looks like, for a little bit. Let’s go to another phone call and see if we can get as many in here. Let’s go to James in Americus, Georgia. Hi, James.

JAMES: Hey, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Hey, there.

JAMES: I have a question. Are jellyfish immortal? Can they go on living?

IRA FLATOW: Juli, what’s a life of jellyfish?

JULI BERWALD: Jellyfish have a really cool and complex life cycle. The egg and the sperm form a little larvae called a planula that settles and becomes polyp. And then that polyp goes through this really amazing stage called strobilation where it slices itself into like a stack of pancakes. And then each pancake bursts off the stack and becomes a little free-swimming jellyfish called an ephyra which matures into the medusa that you’re probably familiar with.

There are a few species of jellyfish that are known to be able to go from the medusa backwards through their lifecycle to the polyp stage and then back forward again to the Medusa and backwards to the polyps. So those jellyfish have been named the immortal jellyfish.

And they are actually looking at them because not only does the animal go backwards, the cells in the animal go back to stem cells which isn’t something that we really know much about. They’ve been able to do it in culture, to take fully-baked adult mature cells and go back to stem cells. But in animals it’s very unknown. And so they’re looking at that now to see how the jellyfish does it and what we might be able to learn from it.

IRA FLATOW: Far out, as we used to say. Let’s go let’s go to Matt in Wallingford, Connecticut. Hi, Matt.

MATT: Hi. So I have two questions. One was, you just talked about the, quote unquote, “immortal jellyfish.” So is there any research so far in how that immortal jellyfish goes back, quote unquote, “in its developmental cycle and then forward again?” Is that just the system stopping and then somehow going back and then doing something else?

And also the other question was how do we differentiate between different jellyfish? If, let’s say, I go swimming and I see a jellyfish or something, how would I, as a casual observer, differentiate the different types of jellyfish?

And, as a scientist, if, let’s say, you’re trying to look at the quote unquote, “immortal jellyfish,” how are you supposed to figure out, just by looking at it, that yeah, it is the immortal jellyfish and it’s not some other type of jellyfish?

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let me get an answer. Lucas, how do you know one jellyfish from the other?

LUCAS BROTZ: Yeah, for sure. There’s thousands of species of jellyfish out there that have been identified and probably tens of thousands more that we have yet to discover and identify. So it can be a challenge to identify the different ones. Obviously some jellyfish look very different from each other in terms of size.

The giant jellyfish in Japan can get to be up to 500 pounds and six feet across. And then the immortal jellyfish that we’ve talking about usually isn’t much bigger than your pinky finger nail. So there’s certainly some jellyfish that look quite different than others.

But once you get closer related between different species it can be a challenge. But there are subtle differences that we use to identify one species from another. And then, of course, DNA barcoding as well. You can look at the genome of the different jellyfish and that really gives you a clue to whether or not they’re different species.

IRA FLATOW: I am running out of time. I’m sorry to interrupt you. One quick question for Juli. You still have a jellyfish tank in your house?

JULI BERWALD: No. That wasn’t very successful. It’s kind of like having a carnival goldfish. It didn’t make it too long. It’s tough work. You really have to have, I think, a pretty big filtration system.

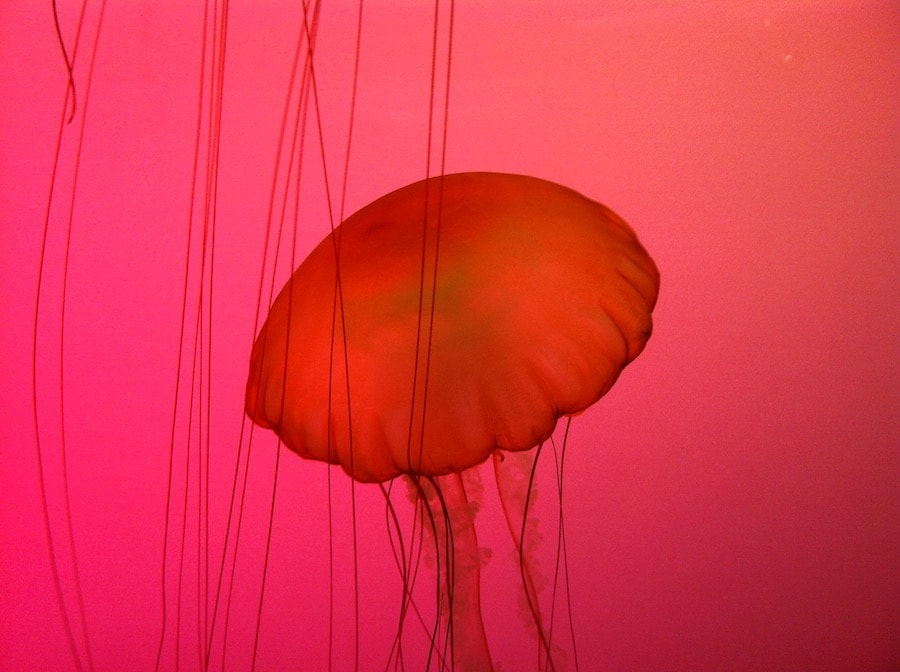

IRA FLATOW: Saltwater aquariums are tough. I used to have a little reef in my house, I understand. I get it. Juli Berwald, science writer and author of the new book, Spineless. You can find an excerpt of her new book on our website along with some beautiful photos at sciencefriday.com/jellyfish. Lucas Brotz, post-doctoral researcher in the Institute for Oceans and Fisheries. University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

JULI BERWALD: Thank you.

LUCAS BROTZ: Thanks very much.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.