Mining Coal For Clues About Ancient Environments

12:23 minutes

Coal is the official state mineral of Kentucky, but it’s more than just a dirty black rock that’s mined and burned. Geologist Jen O’Keefe uses coal as a time capsule, studying the pollen, spores, and plant material fossilized inside. She talks about what these microscopic clues can reveal about what the environment was like millions of years ago.

Plus, Science Club wrap ups up the Neat Rock Challenge, highlighting some of the geologic wonders—from limestone to agate—submitted by club members for the digital rock collection.

View Science Club’s virtual neat rock collection here.

Jen O’Keefe is a Professor of Geology and Science Education at Morehead State University in Morehead, Kentucky.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow at the Brown Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky.

[CHEERING]

Tonight’s theme is On the Rocks. And Kentucky has a proud geologic history. There’s the limestone that helps make the caves. There’s agate, the official state rock. And even though it’s not actually a mineral, the official state mineral is coal. But we wanted to look at coal in a new way. And I want you to think of coal not as just a dirty black rock that burns, but as a time capsule. And joining us now to open that time capsule is Jen O’Keefe. She’s a professor of geology and science education at Morehead State University. She’s also a palynologist. I get that right?

JEN O’KEEFE: You got that right, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: An expert on spores and pollen. Welcome to Science Friday.

JEN O’KEEFE: Thanks. It’s good to be here.

[CHEERING]

IRA FLATOW: Now, you look at a piece of coal. What you see there that we don’t? What is your interest in studying coal?

JEN O’KEEFE: I’m really interested in why we have coal in the first place, and what it can tell us about ancient environments. We’re watching our environments change in crazy ways now, and we don’t have great records on how they’ve changed in the past for most people. Little things from I drive back and forth to Texas a lot, and it used to be you didn’t see a dead armadillo until you got to the Texas border. Now we see them in western Kentucky. Why is that?

We’ve got this great time capsule in our backyard that we can start to pick apart. And a lot of the picking it apart is on the microscopic level. And when I start looking, I see the intricate details hidden from view.

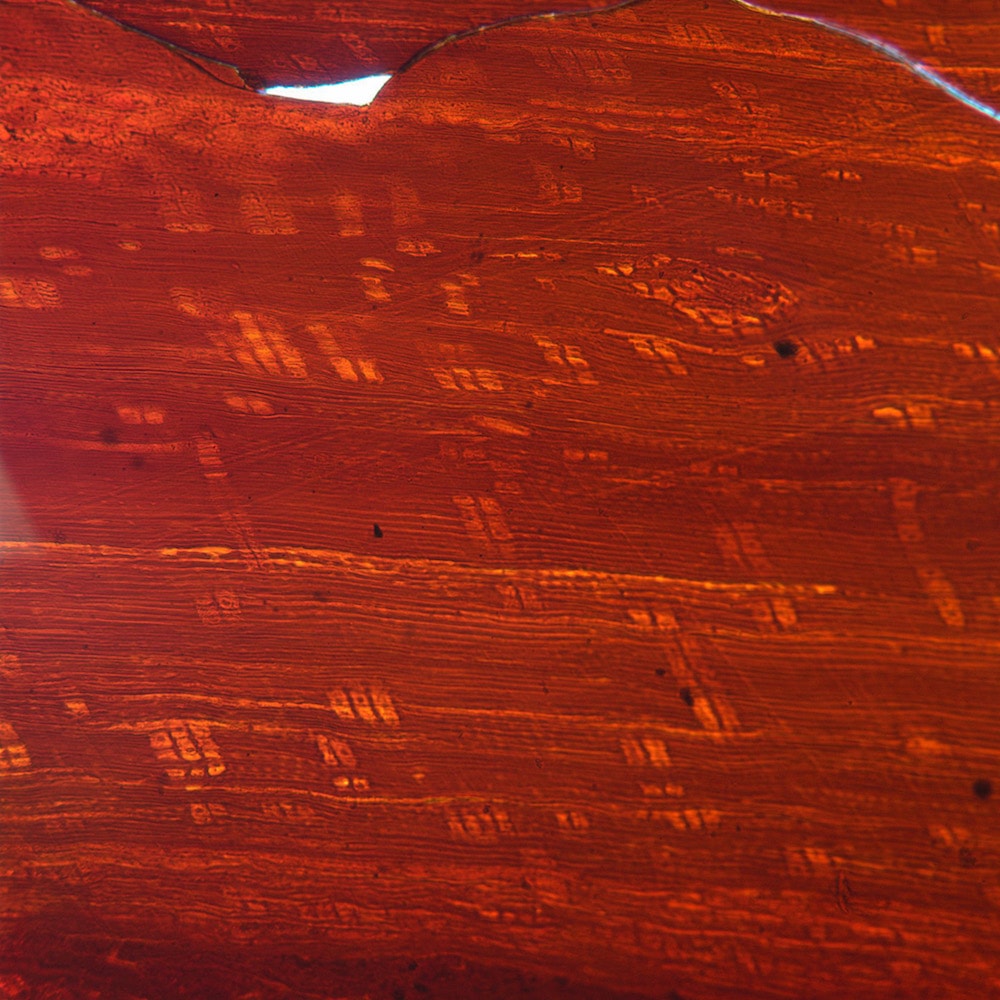

IRA FLATOW: Can you actually slice the coal up thin enough?

JEN O’KEEFE: We can. We can. We can slice it down to a third of a millimeter thick, and make a thin section.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

JEN O’KEEFE: And at that point, you can see right through it. And you can see the cellular structure of the plants, and the fungi, and sometimes other organisms that are making up the coal. You get really, really cool things.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That’s a beautiful green color all–

JEN O’KEEFE: It is. This is a cannel coal from eastern Kentucky. This one is from near Cannel City. And you’re looking at the glowing algae and spores from over 200 million years ago that make up this particular coal.

IRA FLATOW: So we’re really looking at fossils. The coal is a fossil.

JEN O’KEEFE: Absolutely. The coal is a fossil. It’s fossil plants. It’s fossil algae. It’s fossil fungi.

IRA FLATOW: So tell us what the difference between spores and pollen. What’s the difference when you look at them?

JEN O’KEEFE: OK, so spores are a form of usually unisexual reproduction. There’s some interesting fossil plants that seem to have two kinds of spores. Pollen is part of bisexual plant reproduction. The pollen is the male reproductive gamete.

IRA FLATOW: And of course, once you get these things, you can figure out what the environment was when that coal was produced?

JEN O’KEEFE: Right. So for a lot of the coals we look at, we see many, many, many pollen grains or many plant spores, depending on if we’re before angiosperms, which produced pollen evolved, or after. Here in Kentucky, most of our coals contain plant spores, because they’re produced long before. Where I work in the Gulf Coast, and in China, and in other countries, we see a lot of angiosperm pollen. But along with both of these, we see an awful lot of fungal spores.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

JEN O’KEEFE: And that had us scratching our head going, could we help modern mycologists tie their evolutionary lineages directly to the fossil record? So we started working with a bunch of modern mycologists from Argentina, where they are training people still in the almost-lost art of recognizing fungi using–

IRA FLATOW: Mushroom.

JEN O’KEEFE: Recognizing mushrooms just using the spores.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Can the fungi that you see tell us about anything about the animals that lived during this time?

JEN O’KEEFE: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. We have been doing a lot of work up on samples from Big Bone Lick with Craft Academy students from Morehead State. This is our residential high school. And they’re finding all kinds of fungal spores that only grow on dung, so the poop spores.

The fun part about this is we have some fungi, like ascobolus, that really, really, really like to grow on waterfowl poo. We have no bones of waterfowl from Big Bone Lick. We have bones of big things from Big Bone Lick. Now we know we had waterfowl, too.

IRA FLATOW: See if I have a– do you have a question? Yes. Step up to the mic.

AUDIENCE: Is there any specific type of coal that works best for your research, or is it just any coal?

JEN O’KEEFE: We look specifically for coal that’s not very woody. If it’s too woody, we don’t see a lot of pollen and spores. We just see wood fragments.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Yes, step up.

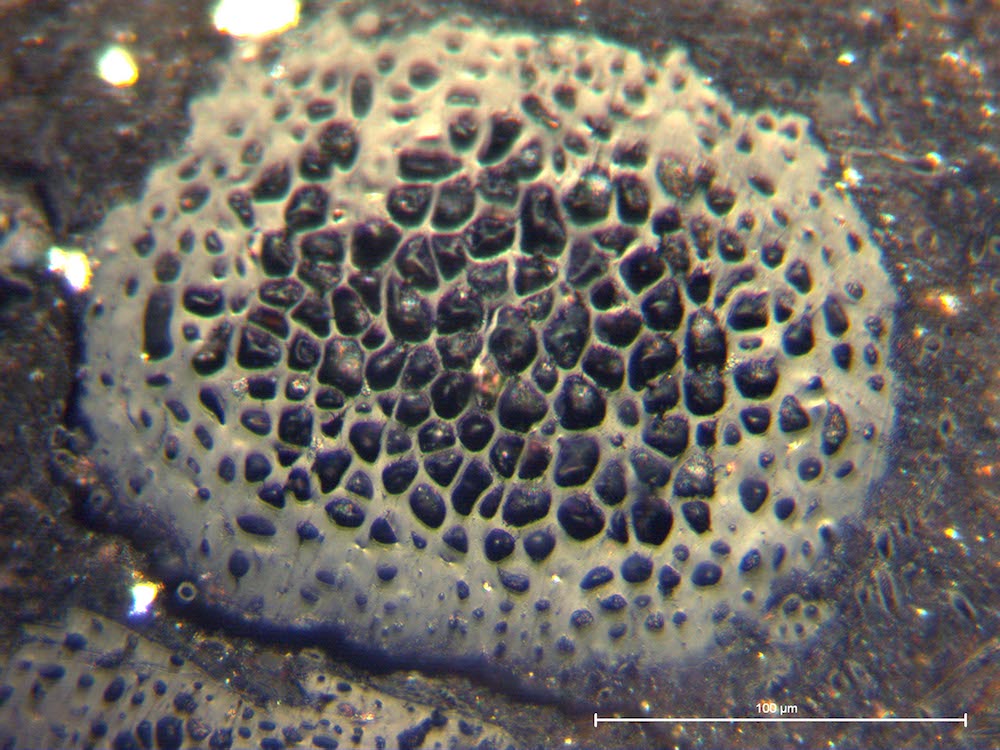

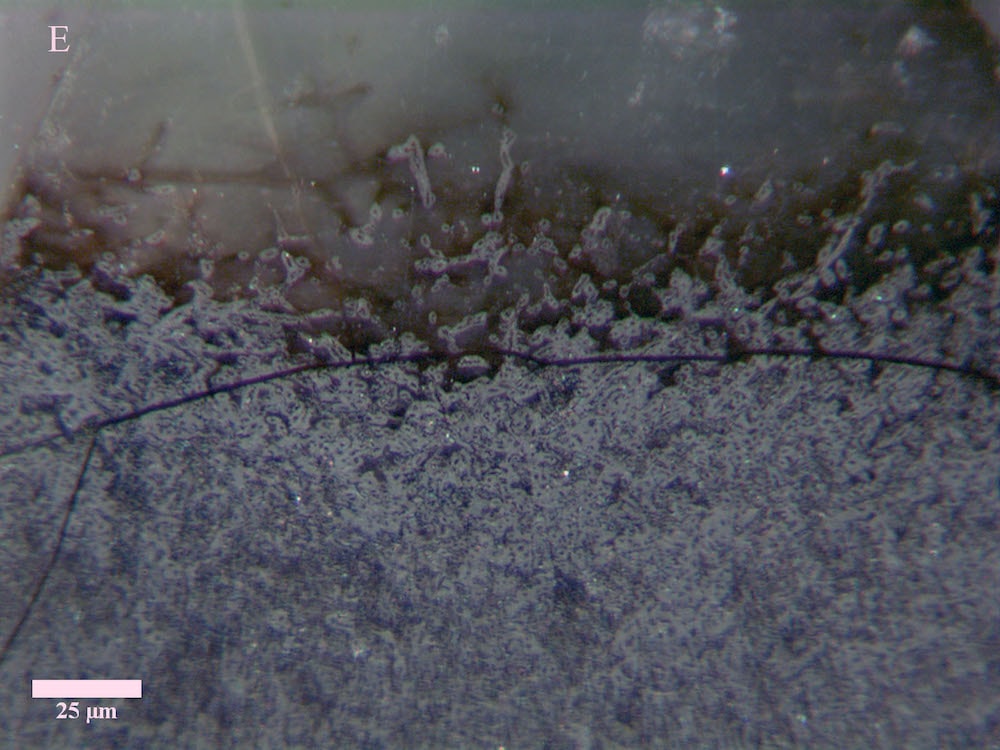

AUDIENCE: So when you’re looking at a slice of coal and you see like a 200 million-year-old fungi spore, how do you identify what type of fungi it is?

JEN O’KEEFE: Well sometimes, they have specific ornamentations, so they have decoration on the outside of the fungus that’s very distinctive. Sometimes we have to sit down and make very, very precise measurements, and extract it from the coal, and look at it by itself, and roll it around, and put it under an SEM, and take detailed pictures. And there’s some we can’t identify because a lot of fungi, especially basidiomycetes, make simple spores that are really tough to tell apart.

IRA FLATOW: Is the coal uniform around the world?

JEN O’KEEFE: No. There are a lot of variations. So just here in Kentucky, we have three completely different kinds of coal. We have bituminous coal, which is what we tend to mine. We have a little bit of anthracite coal, mostly near igneous intrusions, so near rocks that produced garnets rather than diamonds out in western Kentucky and eastern Kentucky. And out in the Jackson Purchase, we have lignite, which is very, very low rank. You wouldn’t want to burn the stuff at all, but it makes an amazing environmental record.

IRA FLATOW: Do the miners are the extractors ever come to you and say, we got something?

JEN O’KEEFE: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah?

JEN O’KEEFE: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Like what?

JEN O’KEEFE: Very often, they’ll call me up and say, I have this strange ax handle in my coal. Can I bring it to you?

IRA FLATOW: Say that again. You have a strange ax handle?

JEN O’KEEFE: Ax handle in my coal. Can I bring it to you? And I say, oh, sure. Bring it down. And it’s usually a fossil root and sometimes a fossil stem that’s been compressed, and it looks just like an ax handle. It’s pretty neat stuff.

IRA FLATOW: We have a question from this young man here. Yes.

AUDIENCE: When you see the spores, how are you able to know how the plant would look like?

JEN O’KEEFE: So that has taken a lot of work over time, looking for the plants that the spores and pollen came from. We’ve had to go out and work very closely with modern botanists, and paleobotanists, and mycologists, and paleomycologists to try and tie the pollen and spores we see to the organism. And sometimes, we don’t. We have no idea of what some of these things looked like when they were alive.

IRA FLATOW: So I want to thank you for taking time to be with us today. Jen O’Keefe, professor of geology and science education at Morehead State University.

[CHEERING]

We’re On the Rocks tonight. And recently, Science Friday took a deep dive into geology with our Science Club. I hope you’re a member of our Science Club. And here’s Charles Bergquist, Science Friday’s director. He’s the guy behind all the controls in the control room, and one of the founding members of the Science Club, to talk about that. Welcome, Charles.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Thank you, Ira. It’s good to be here.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Tell everybody who’s not familiar with our Science Club what the Science Club is.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So the Science Club is our occasional invitation for people to go out, do science, and share it with others. You may be familiar with a book club, where everybody goes and reads the same book, and then talks about it. We challenge you to go and do something and then talk about it.

IRA FLATOW: Give us an idea.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So in the past, we’ve had people make a machine that makes art. We’ve said, go out and just figure out some way of making an art machine for us. A couple weeks ago, we had people try to make new forms of ice, or make their ice better.

IRA FLATOW: Make your ice better.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Make your ice better. Could be a good homeschool.

IRA FLATOW: And then also, we had a project recently that has to do with what we’re talking about tonight. And this was really exciting, rocks. Tell us about the rocks project.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So in the beginning of October, we said, everybody’s got that neat rock. You’re out for a hike. You’re at the lake. And you go, oh, wow. That’s so cool. I’m going to take this home with me. I don’t know what it is. I’m going to put in my sock drawer.

[LAUGHTER]

And we thought, wouldn’t it be great if we could all share those neat rocks with each other, and maybe hopefully find out a little bit more about them? So we partnered up with the American Geophysical Institute, which is the big organization in the United States, and they provided us with a bunch of helpful explainers, 43 different geologists who teamed up with this to try and build our digital rock collection.

IRA FLATOW: And how did that work out? Was it successful?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: It was maybe a little too successful. We got over 1,000 rocks.

IRA FLATOW: Whoa.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Representing all–

IRA FLATOW: They sent you actual rocks?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Only a few. Most of them were just pictures, like the ones you’re seeing here, pretty pictures of all kinds of super cool things that people sent to us. So all 50 states, 41 different countries. And so as you can imagine, it’s taking a little bit of time for our 43 volunteer geologists to help classify and explain all 1,000 rocks. So if any of you people out there sent in a rock to us, we’re going to get you. We’re still working on it.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Now that we’re in Louisville, what about Kentucky? Did we get any from Kentucky?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: So Kentucky has a proud geologic history. And we had several rocks sent in that were very closely connected to this state. One is limestone. Limestone is largely part of why you have so many cool caves. Some people say that the limestone is also partially responsible for the water that gives all of your fine distilled beverages such a nice flavor.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And so are you still taking rocks? Are you still waiting for people to send pictures in?

CHARLES BERGQUIST: We’re going to be moving on to another project.

[LAUGHTER]

I encourage all of you to become a member. You can find out more at sciencefriday.com/scienceclub.

IRA FLATOW: Charles Bergquist, thank you very much.

CHARLES BERGQUIST: Thank you, Ira.

[CHEERING]

IRA FLATOW: The director. Throughout the show, we have a special treat for you, some musical entertainment. Ladies and gentlemen, welcome Bridge 19. Give them a big hand.

[CHEERING]

[MUSIC – BRIDGE 19]

BRIDGE 19: [SINGING] I was marching in your footsteps Always walking right behind. Sleeping soundly, safely surviving in a shelter filled with life. But it’s been so long. Now I know you’re wrong. And you’ll watch your house burn down. Smoke is rising. Tables are turning. Running for the exit signs. Flames are–

IRA FLATOW: This is–

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.