The High Cost Of Notifications

The more you’re interrupted, the more likely you are to interrupt yourself. Can we win the war on our prefrontal cortex?

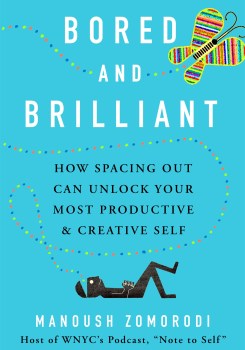

The following is an excerpt from Bored and Brilliant by Manoush Zomorodi.

Immediacy is a simple fact of modern life. Texts, in some form, are here to stay. However, there are serious costs to us from these constant intrusions on our attention, according to research by Gloria Mark, a professor of informatics at the University of California, Irvine. “About ten years ago, we found that people shifted their attention between online and offline activities about every three minutes on average,” she said. “But now we’re looking at more recent data, and we’re finding that people are shifting every forty-five seconds when they work online.”

This isn’t just a productivity or focus issue. Mark’s lab has found that the more people switch their attention, the higher their stress level. That is especially concerning, she says, because the modern workplace feeds on interruptions. Dubbing the group of workers most affected “information workers,” she said this population “might have every intention of doing monochronic work, but if their boss sends them an e-mail or they feel social pressure to keep up with their e-mails, they have to keep responding to their e-mails and being interrupted.”

Bored And Brilliant: How Spacing Out Can Unlock Your Most Productive Self

“I think that if people were given the ability to signal to colleagues or just even to signal online, ‘Hey, I’m working on this task, don’t bother me, I’ll let you know when I’m ready to be interrupted,’” she said.

But you can’t blame your coworkers or your children or your Gchat buddy for everything. Guess who is the person who actually interrupts you the most? Yourself. Mark’s lab has a term for this—the “pattern of self—interruption.”

“From an observer’s perspective, you’re watching a person [and] they’re typing in a Word document. And then, for no apparent reason, they suddenly stop what they’re doing and they shift and look at e-mail or check Facebook. These kinds of self-interruptions happen almost as frequently as people are interrupted from external sources,” Mark said. “So we find that when external interruptions are pretty high in any particular hour, then even if the level of external interruptions wanes [in the next hour], then people self—interrupt.

In other words, if you’ve had a hectic morning dealing with lots of e-mail and people stopping by your desk, you are more likely to start interrupting yourself. Interruptions are selfperpetuating.

Harris characterizes the current state of affairs that Mark describes as a “new kind of pollution, an inner pollution.” Even someone like Harris, who thinks about this issue all the time, isn’t immune to digital seductions. Before our conversation, he admitted he’d checked his e-mail and news feed “twenty times.” No one’s brain stem is immune.

[To master test materials, you might want to give your brain a break.]

But the source of Harris’s true fear that we are losing the ability for reflection, restraint, and concentration comes from his personal experience running a start-up in Silicon Valley. “I’d walk into an office of an online publisher and say, ‘We can double or triple the amount of time people spend on your Web site,’” he told me. “It’s a moral conundrum that I faced as a founder and why I care a lot about this issue.” The essence of the conundrum for any fledgling tech entrepreneur is that your ability to raise capital is based on proving you can exponentially grow usage.

As part of his desire to change “how we measure success,” Harris began working on what he calls “design ethics,” conversations and practices that can return some control over our technology back to the “user” and, in turn, increase the value of the time we do spend with our devices. As part of this movement, which he calls Time Well Spent, he holds small designer meet-ups to share best practices, new forms of incentives, and products that “measure success in their net positive contribution to people’s lives.”

Is that even a real metric? According to Harris, it is. In 2007, Couchsurfing, a precursor site to Airbnb, where people could find places to stay for free all over the world, measured success in the “net positive hours that were created between two people’s lives.” The site used data such as how much time the couchsurfer and the host spent together and how positive the experience was (i.e., “Did you have a good time together?”). By Couchsurfing’s calculus, the time two people initially spent searching profiles, sending messages, and setting up a stay on the Web site was factored as a negative, because “they didn’t view that as a contribution to people’s lives.” That time was therefore subtracted from the original gains. “What you’re left with is net positive hours that wouldn’t exist if Couchsurfing didn’t exist.” When I asked if this metric actually worked, Harris said that Couchsurfing, which was founded was back in 2007, no longer exists.

In the age of Tinder—the behemoth dating app whose success in 2016 is measured to the tune of 1.4 billion swipes a day rather than soul mates—I’m not optimistic.

When I asked if this metric actually worked, Harris said that Couchsurfing, which was founded was back in 2007, no longer exists.

Despite becoming so absorbed in our apps that we’ve lost sight of their original purpose, we should mobilize (pun intended), not despair, according to Harris, who views tech’s evolution as parallel to so many other industries—including food’s cheap, empty calories and banking’s predatory lending. “I hate to say this, but if you surrender to the default settings of the world, they are designed to take advantage of you,” he said. “Everything requires vigilance.”

To take back our minds from apps like Pokémon Go, Harris advocates a political stance akin to what happened in the organic food movement, when consumers, angry over the unintended, detrimental effects of mass agricultural production, demanded new standards. We should imagine a world where success is aligned with the fulfillment of the user’s original goals. Did you relax, feel connected to faraway friends, discover a new way to decorate your kitchen? The metric by which sites and apps should be rewarded, Harris argues, should revolve around the answer to this question: “Whatever people were looking for, did they get it?”

[Is it time to rethink our relationship with our phones?]

That sounds great. So do debt-free college, zero-waste homes, and a lot of other enormous societal visions, which are enormously difficult to make a reality. In the immediate term, Harris says, “The most important thing to acknowledge is that it’s an unfair fight. On one side is a human being who’s just trying to get on with her prefrontal cortex, which is a million years old and in charge of regulating attention. That’s up against a thousand engineers on the other side of the screen, whose daily job is to break that and keep you scrolling on the infinite feed.”

Bored & Brilliant by Manoush Zomorodi. Copyright © 2017 by New York Public Radio and reprinted by permission of St Martin’s Press.

Manoush Zomorodi is host of the TED Radio Hour, and author of the book Bored and Brilliant. She’s based in New York, New York.