Up On The Roof, A Handful Of Urban Stardust

A jazz musician-turned-micrometeorite hunter gives advice on how to search for the tiny bits of cosmic dust that could be covering your rooftop.

Urban micrometeorites. © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

The cosmos is a swirling soup of stardust. Every day, approximately 60 tons of dust from asteroids, comets, and other celestial bodies fall to the Earth. These tiny metallic, alien stones of various shapes, textures, and colors—known as micrometeorites—are some of the oldest pieces of matter in the solar system.

Even though micrometeorites blanket the Earth, scientists have generally only been able to discover them in remote places devoid of human presence, such as Antarctic ice, desolate deserts, and deep-sea sediments. Scientists began searching for micrometeorites in the 1960s, and they predominantly thought the extraterrestrial dust would be impossible to find in urban environments. The conventional wisdom held that densely populated areas had too much man-made sediment that camouflaged the tiny space particles.

[Prospecting for Martian gold in Antarctica.]

But Jon Larsen, a Norwegian jazz musician and creator of Project Stardust, was able to show that it is possible to find micrometeorites in more populated areas. In a study published in January 2017 in the journal Geology, he and his colleagues catalogued more than 500 lustrous micrometeorites (and counting), all recovered from rooftops in urban areas.

“It is possible to find the most exotic, small rocks in the entire universe in your roof’s rain gutter,” Larsen wrote to SciFri in an email. A collection of micrometeorites and other artificial and terrestrial particles are compiled in a new book, In Search of Stardust: Amazing Micro-Meteorites and Their Terrestrial Imposters published in August by Voyaguer Press.

[Meet the geologist searching for life in meteorite impacts.]

Larsen began his quest for urban micrometeorites in 2010 after one landed on his porch table while he was eating breakfast. Over the past seven years conducting thousands of field searches in nearly 50 countries, he has found everything from chondritic spherules to volcanic residue to cigarette spark debris. His photo database now contains over 40,000 terrestrial and space particles.

Larsen has some tips for intrepid stardust hunters. “The easiest way to find a micrometeorite is to start with the right roof,” he says.

Large, flat roofs covered with vinyl and surrounded by walls are perfect for accumulating particles. On a dry day with a broom and some plastic bags in hand, he safely goes atop a roof (after gaining necessary permission) and sweeps up loose particles. Meteorites are typically magnetic and have high iron content. Larsen is able to collect magnetic material (including potential micrometeorites) on the spot with a handheld magnet.

[The sands of Earth, and beyond.]

In a lab, he’ll rinse the sample with water, screen it for size (micrometeorites typically fall between 0.2 to 0.4 millimeters), and “start to search for the proverbial needle in the haystack” with a microscope. With the assistance of the Imaging and Analysis Center at the London Natural History Museum, Larsen uses scanning electron microscopy and electron microprobe analysis to determine the mineralogy and identification of the particles.

While this process works for Larsen, he encourages future micrometeorite hunters to continue coming up with new ways to find them. “We are just in the beginning of this, so it’s better to use your imagination and perhaps find better ways to do this,” he says.

It took Larsen seven years to systemize all the types of micrometeorites, terrestrial particles, and industrial contamination because he had very little reference material to tell him what to look for in the field. His new book doubles as a visual roadmap that guides you through the dust, making it possible for anyone anywhere to find micrometeorites, he says.

“It’s fun, and the reward when you are face-to-face with the oldest matter in the solar system is very satisfying,” Larsen says. “We humans are basically hunters, and hunting for stardust is a peaceful activity I recommend to everybody everywhere.”

To begin identifying micrometeorites on your own, explore a selection of various kinds of tiny particulates (both from space and Earth) featured in Larsen’s new book, In Search of Stardust.

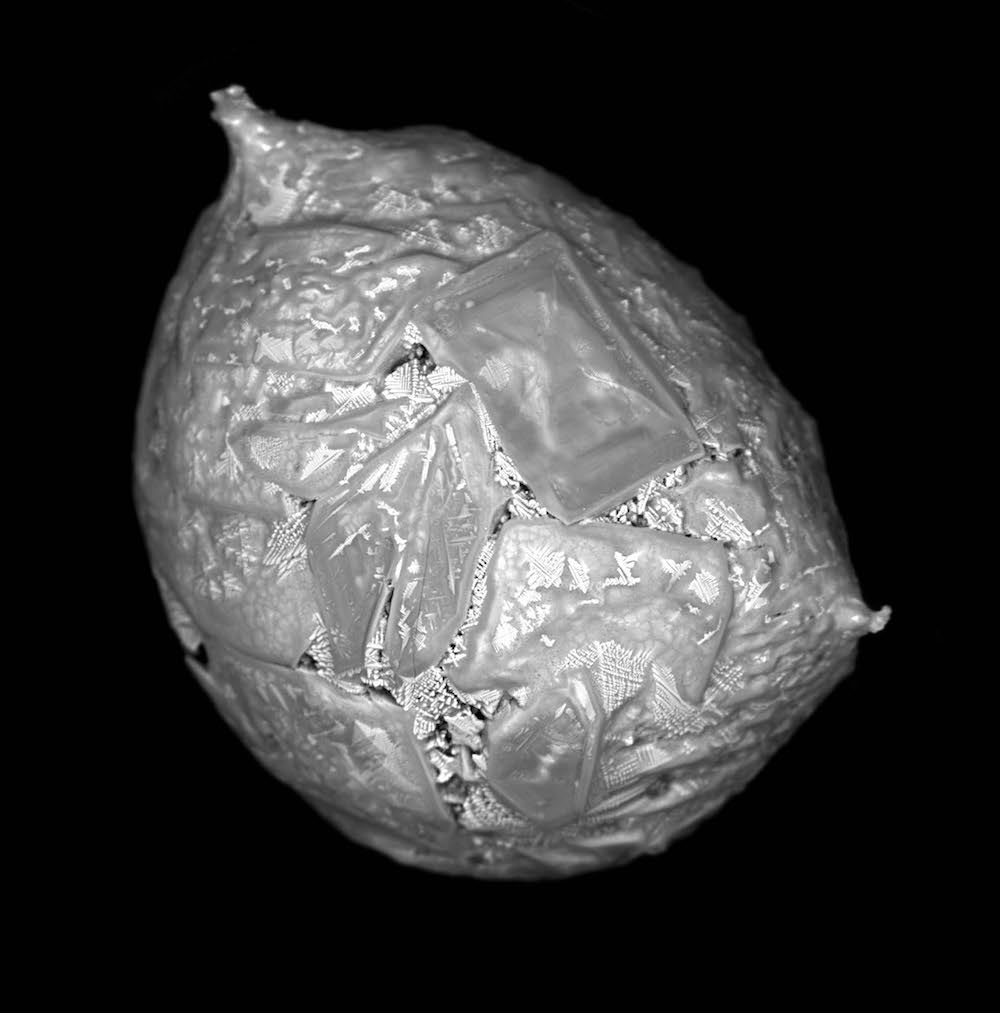

A series of “black beauties” or cryptocrystalline micrometeorites. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

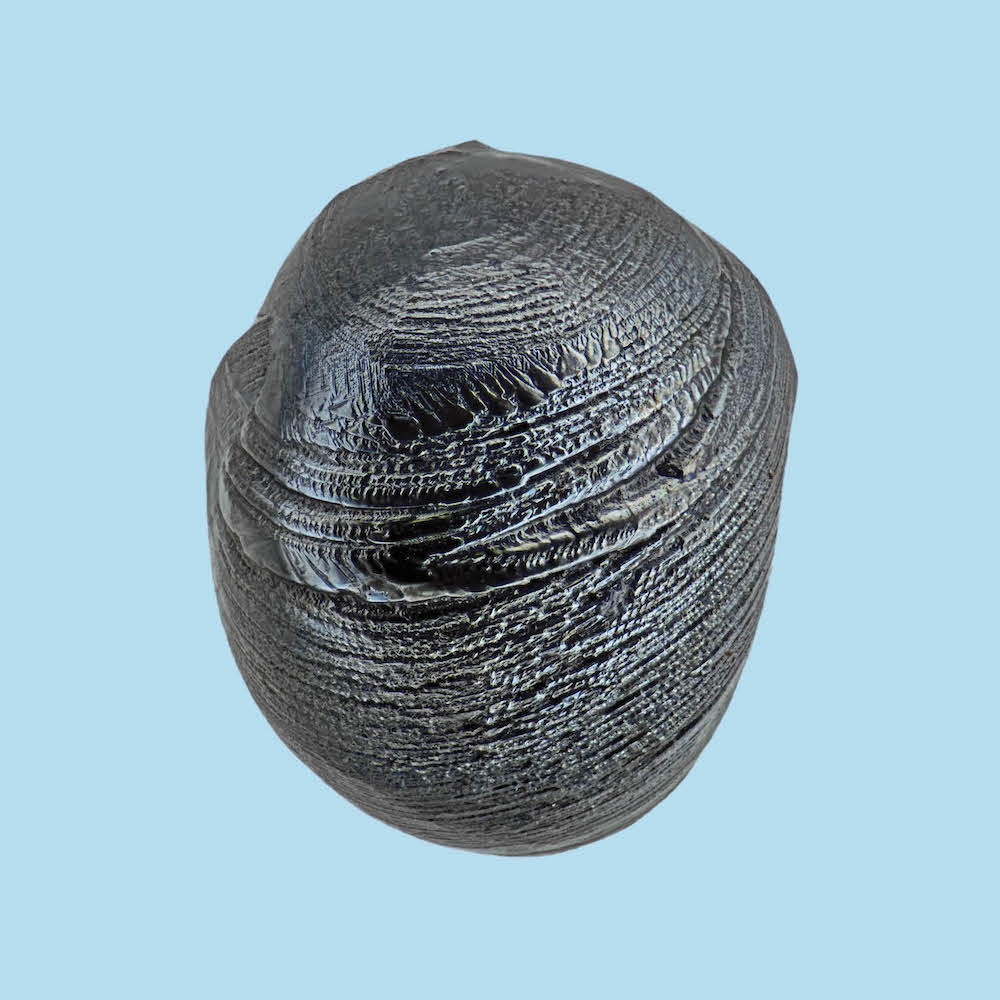

A sulphide rim flows out from the metal mound of this micrometeorite. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

This barred olivine micrometeorite has two metal beads. The difference in color between the two beads is possibly due to different levels of metals; the one of the left contains more nickel, while the one of the right has more iron sulphide. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

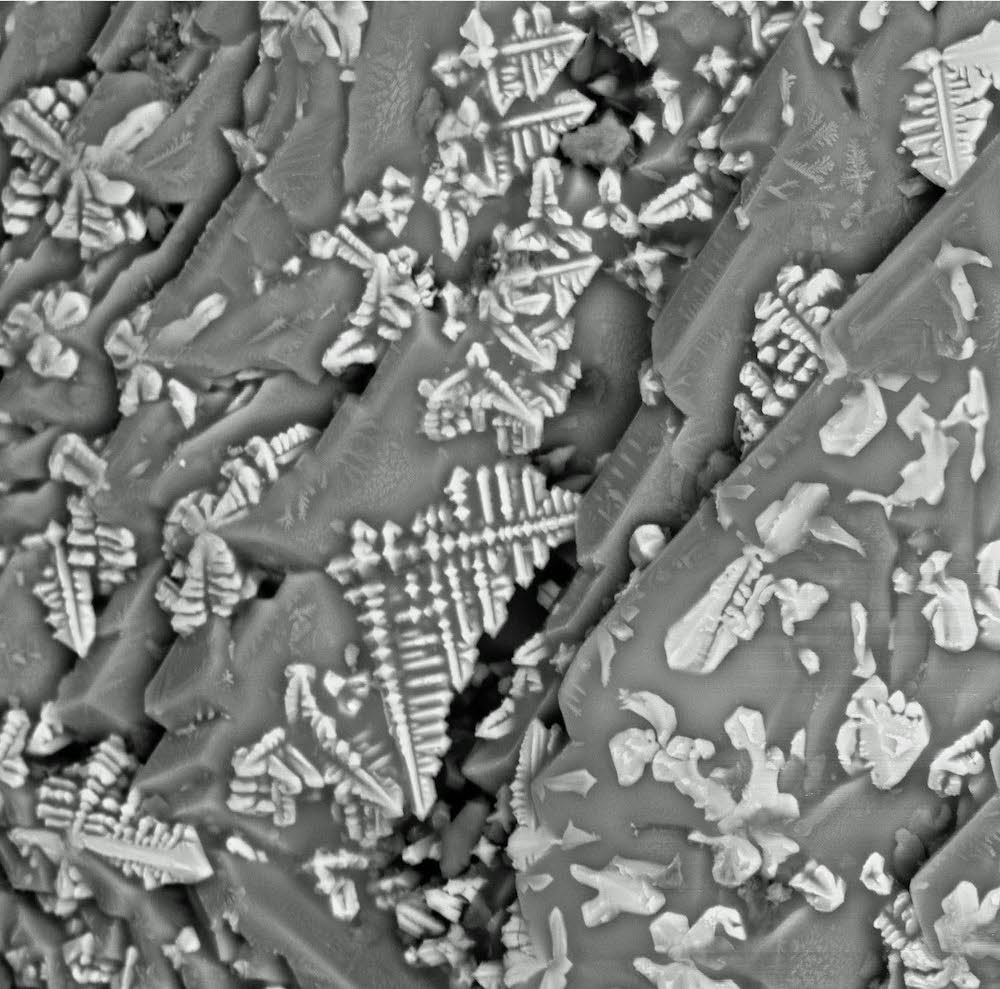

Using scanning electron microscope, Larsen was able to get a detailed view of the unique surface textures of the micrometeorite, helping with identification. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen

Dendritic magnetite, that look like tiny pine trees, forms on micrometeorites when the iron in the stone reacts with the oxygen in the atmosphere upon entry into the Earth. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen

The cryptocrystalline micrometeorite has a nickel, chromium bead. It’s also called “turtleback” for its texture and shape. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

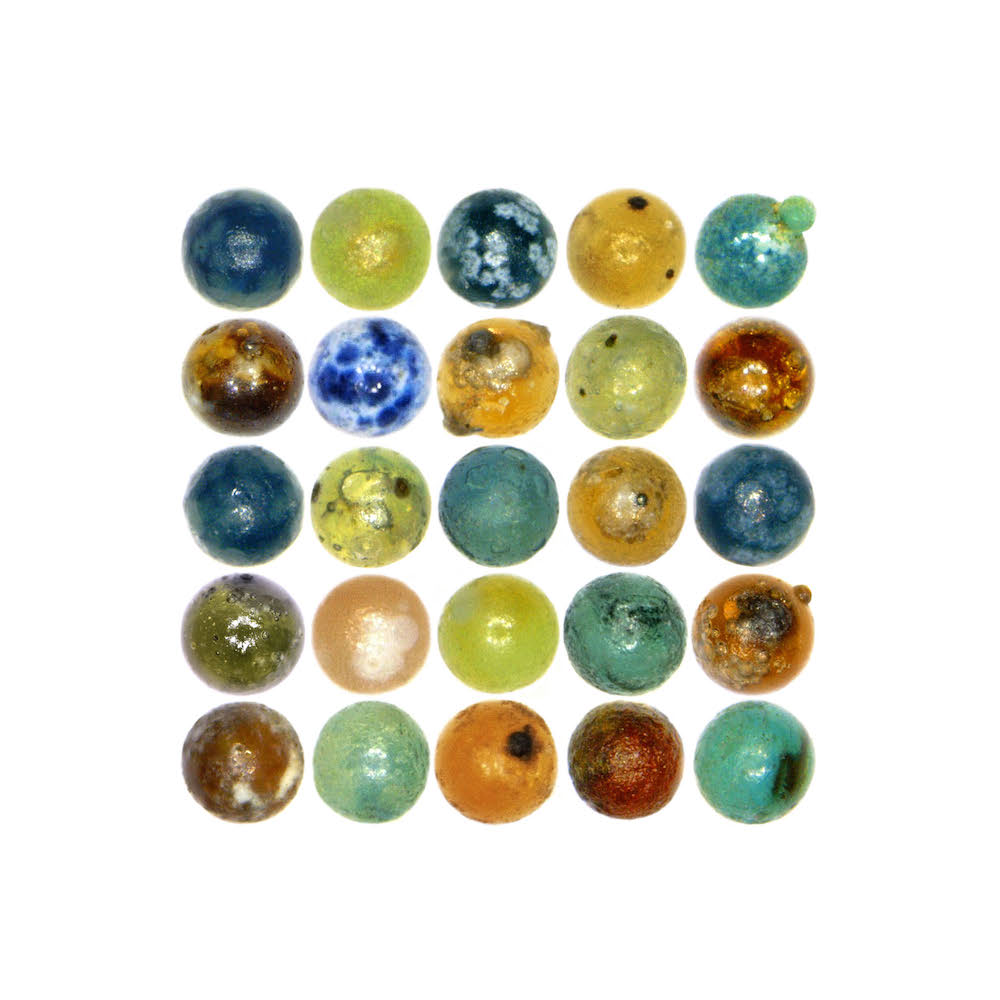

This micrometeorite has a relatively large nickel and iron core. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle A melted V-type (vitreous) micrometeorite, approximately 0.25 millimeters, with an iron, nickel bead. The reflection at the bottom is a small internal vesicle. It was <a href="found in December 2015 at Nesodden, Akershus, Norway. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle Glass micrometeorites. The translucent amber micrometeorite (top right) with five nickel beads was an unusual find from Kvam, Oppland, Norway, on October 2015. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle The sparks from fireworks and flares create spherules of various colors from the metal salts. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

Since many micrometeorites are found on roofs, erosion from roof tiles and shingles can also be confused for the prized extraterrestrial pebbles. Ceramic tiles can contain pigmented iron rich glue that could be picked up by a magnet. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

Mineral wool can easily be mistaken for micrometeorites to those with an untrained eye. The mineral found in products such as insulation has little droplets and spherules that look similar to micrometeorites. Chemical analysis will reveal that it’s not a micrometeorite. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle Volchovites, a type of crypto-volcanic glass. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

A large (approximately 0.6 millimeter) barred olivine micrometeorite found in Norway on December 2015. Credit: © 2017 Jon Larsen/Jan Braly Kihle

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.