Could ‘Green Spot’ Be Sign Of Trouble For Oroville Dam?

5:20 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story originally appeared on KQED Science.

From Day 1 of the Oroville spillway crisis in February, the California Department of Water Resources has never wavered in its declarations that, despite the disintegration of the massive concrete flood control outlet and a near-disaster caused by uncontrolled emergency reservoir flows down a rapidly eroding hillside, the stability of the massive dam itself was not and has never been threatened.

Despite those oft-repeated assurances, public questions about the dam’s integrity have persisted — in internet forums, in community meetings and, most recently, in a report released last week under the auspices of UC Berkeley’s Center for Catastrophic Risk Management.

That’s in part a reflection of public distrust of DWR after the spillway incident and in part a recognition that anything that seriously compromises the 770-foot-tall dam could endanger tens of thousands of lives, cripple a key element of California’s water-supply network and put the state’s entire economy at risk.

[Has California’s five-year drought washed away?]

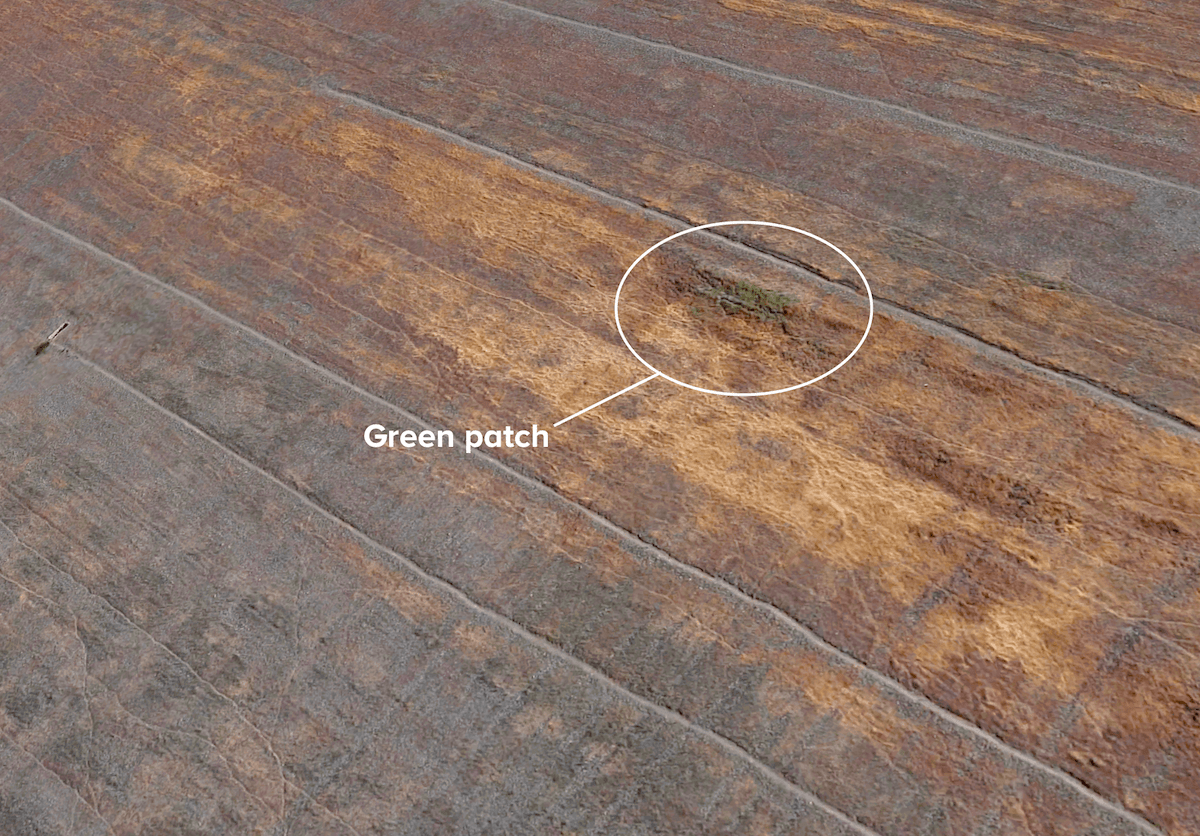

Specifically, the questions have focused on an extensive area of moisture on the left side of the dam’s downstream face that’s known, even to the Department of Water Resources, as “the green spot.”

The spot, characterized by what state inspectors have termed “lush” vegetation during wet seasons that turns into dense thickets of dry weeds by late summer, is clearly visible on satellite images and measures about 700 feet long by 130 feet wide. That’s roughly the size of two football fields.

Last week’s study, led by internationally known civil engineer and risk management analyst Robert Bea, included several subreports asking whether the moisture at the green spot is a sign that water is leaking through the dam and weakening its inner structure.

Publicly, DWR officials have tended to dismiss those concerns. In response to questions at community meetings in Oroville and Yuba City in May, for instance, the agency said the green area is due to rainfall, that it first appeared while the dam was under construction, and that it poses no risk to the dam.

But outside public view, documents KQED obtained under the California Public Records Act show the Department of Water Resources has puzzled for years over the source of the seepage feeding the “green spot” and has been slow to act on a 2014 recommendation from independent experts to investigate the issue.

DWR’s uncertainty is reflected in a series of dam inspections between February and July 2011 — Northern California’s last wet winter before the five-year drought — that produced contradictory conclusions about the issue and whether it was a chronic condition or something that appeared only seasonally.

On Feb. 2, 2011, a DWR inspection party hiked to the green spot — about 200 vertical feet below the top of the massive structure — and found extensive moisture.

“The cause of the seepage has yet to be determined,” wrote Bill Pennington of DWR’s Division of Safety of Dams (DSOD).

One possibility, he said, was rainwater may have collected — or become “perched,” in engineering parlance — within the dam’s embankment. Another possible source: an area of seepage that had been noted in the dam’s abutment during construction in the 1960s.

Pennington suggested that the area should be monitored and “unexpected changes should be reported to DSOD.” In a field notebook, Pennington wrote that Paul Dunlap of DWR’s Dam Safety Branch was “thinking of mapping the area.”

After a May 2011 inspection visit, Pennington wrote that “the long-established wet area at mid-slope on the left end of the dam remains active” and recommended continued monitoring.

In July 2011, with the lake level unseasonably high — less than 2 feet below the edge of the dam’s emergency weir — DWR’s Paul Dunlap returned to check out the green spot. He found it had “essentially dried up.”

“The drying out of the green spot (especially under high reservoir conditions) provides further evidence that the green spot phenomena on the dam is associated with precipitation or abutment seasonal spring activity and not seepage through the dam,” Dunlap wrote in a report on his findings.

Those periodic observations continued — sometimes the green spot was wet, sometimes dry — along with Pennington’s repeated recommendation that dam managers figure out how to monitor the area “so that year to year changes can be recorded.”

In August 2014, an independent board met to perform the dam’s five-year federal safety review. The board’s recommendations, released in December, called on DWR officials to investigate the green spot and try to determine whether it posed a threat to the dam.

“This issue has a high historical profile that needs to be conclusively addressed,” the consultants commented in one section of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s 2014 Part 12D report.

The board said that while much of the dam’s behavior was understood, “one issue that seems to not have been addressed by previous stability analyses is that associated with the green spot on the downstream face of the dam.”

The consultants’ report noted that the final construction report for the dam, which went into service in 1968, indicated that the green spot area was observed even before Lake Oroville began rising behind the structure.

“The green spot is believed to be associated with pre-existing natural springs in the downstream left abutment area of the dam foundation,” the Part 12D report says. The concentration of moisture, the document speculates, could be due to the composition of the rock and earth used to build the dam’s downstream embankment. The fill, which may contain excessive volumes of very fine, dense material, “may prevent free drainage of flows from those underlying springs.”

The four consultants said that although there was no evidence of movement or instability in the green spot area, they recommended the Department of Water Resources investigate to see whether the persistent moisture could pose a risk to the dam, especially in the event an earthquake occurred during a period of particularly wet conditions.

In response, the Department of Water Resources has told the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission it intends to answer questions raised in the 2014 safety board report by September 2018.

The department last year got approval to bore a hole as deep as 150 feet in the dam’s left abutment, adjacent to the green spot area. The drilling was to pursue a separate issue raised by the safety board — the seismic vulnerability of Oroville Dam and nearby facilities. As part of that work, DWR told FERC, it planned to install an instrument for “monitoring groundwater levels in proximity (to) the historic ‘green spot’ within the dam embankment. Data collected may provide beneficial in understanding the origin of seepage within the left abutment.”

After a wave of questions raised by the UC Berkeley Center for Catastrophic Risk Management report issued last week, DWR says it’s preparing a preliminary report on the green spot as well as a longer-term study of the issue. The report is due out next week, DWR spokeswoman Erin Mellon said Friday.

In response to questions about DWR’s response to the safety board recommendations or suggestions for monitoring made in the department’s own inspection reports, Mellon said regular monitoring was ongoing and that “to date, no issues of concern have been noted.”

Bea, the leader of the UC Berkeley study, says that DWR has been complacent in its response to a host of issues related to the dam, including the green spot.

“I think these people are looking at these pieces of evidence and using their logic, ‘Well, this dam’s been here for 50 years. We’ve seen these wet spots before, and it’s performed satisfactorily,’ ” Bea said. “What they’re then concluding is that as you move forward into the future it will continue to perform satisfactorily. That conclusion is premised on a belief there won’t be any changes as you move into the future.”

Bea says that posture is similar to the one the department took to the dam’s spillway. The imposing concrete structure had undergone several rounds of extensive repairs before it failed in February. Despite that history of recurring problems, there’s no evidence that the department considered the possibility that the spillway might need to be rebuilt, and DWR inspections through last August consistently declared the structure fit for continued use.

“They kept thinking (that despite) these early warning signs — ‘Yeah, they’re unusual, we’ve got to put concrete patches on those cracks. And yeah, there are voids under the concrete that we’ll fill with concrete’ — it’s going to remain stable,” Bea said. “That proved to be disastrously wrong.”

Dan Brekke is a transportation and infrastructure reporter at KQED in San Francisco, California.

SPEAKER 1: This is KER–

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: That new kind of button sounds like it’s time to check in on the state of science. It’s a new segment where we’re checking in with public radio stations around the nation to focus on local science news [INAUDIBLE]– the science stories in your backyard. Now first story involves something that we talked about back in February– the Oroville Dam in northern California spilling over, heavy winter rains causing the reservoir to fill up. And the massive amount of water collapsed the main spillway.

So water was released into the never-been-used emergency spillway, and that sent water cascading down the hillside. And that was not a pretty sight, because nearly 200,000 people were evacuated as a precaution. Now a closer look at the earthen dam has revealed something different, too– a mysterious grassy green spot in the soil.

What does all of that mean? Dan Brekke is here to give us an update on the Oroville Dam. He’s a transportation and infrastructure reporter for KQED in San Francisco. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAN BREKKE: Hi, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: First, let’s go back a bit. Give us a thumbnail sketch about the events. What do we know about what caused this spillover of the dam?

DAN BREKKE: Well, you gave a pretty good summary of it. But what happened was that back on February 7th, a large breach appeared in this very large, 3,000-foot long by about 180-feet wide, concrete spillway. And that immediately created big concerns, because the lake was rising because of these storms that you mentioned.

And so after a few days of experimenting with different flows, the lake was getting higher. And eventually, this emergency spillway flowed over. And there was unexpected, very severe erosion that threatened to collapse part of the emergency spillway structure.

And that raised fears of essentially a wall of water racing down the Feather River and wiping out communities downstream. So people got about an hour to pack up and leave.

IRA FLATOW: And the secondary spillway– did that alleviate the problem?

DAN BREKKE: Well, it didn’t, because the idea of a spillway– people have a structure in mind. And what was in place here was just what they call a weir. It’s an overflow structure. So water rises to that level, and it goes pouring over.

And the spillway– what they termed the spillway– was just a naked hillside covered with rocks and brush and soil. And the belief was, on the part of the dam owner– the California Department of Water Resources– that that wouldn’t really cause serious erosion. But that proved not to be true.

IRA FLATOW: So everything has been repaired, holding water now?

DAN BREKKE: Well, we’re in our dry season. They’ve drawn the lake way down. And it’s going to be drawn down all the way through November and December.

There is a massive construction project to get a new serviceable main spillway in place. And the purpose– the state’s intention is to never let that emergency spillway flow again. But I don’t know if nature cooperates with that plan.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s talk about this mysterious green spot that has appeared on the dam. There are different ideas about what this means. What’s it made out of, the green spot?

DAN BREKKE: Well, on the surface, as you said, there is lush vegetation. And when we say “spot,” to just be clear, this is about a two-acre area– so about the size of two football fields.

And what’s happened is that inspectors, for a long time– at least 15 years– have been going, well, we have this lush vegetation, it’s wet over here at certain times of year, but we don’t really know where that water is coming from. And it turns out that if you go back into construction records, there’s actually a picture from 1964, when the dam was being built, of water pooled near what has become known as the green spot.

So the big thing here is it’s an unknown. And a couple years ago– 2014, actually– there is an important state federal dam safety review held every five years. And when that review was held, they said, listen, this is a high profile, historical issue that you need– you, the Department of Water Resources– needs to find a conclusive answer to, where is this water coming from? Because there are concerns that it could be threatening the integrity of the dam.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So we don’t know what it is. And I understand there are 93 other dams in California under review?

DAN BREKKE: Well, the Department of Water Resources, after the ugly surprise of extremely erodable material under the main spillway and the emergency spillway, wants dam owners throughout the state to look at these 93 spillways, actually, to make sure that they’re sound and can take overflows.

IRA FLATOW: Dan Brekke is transportation and infrastructure reporter for KQED in San Francisco. Thank you.

DAN BREKKE: You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: And I guess if you want more information, you could screen Chinatown, the old movie, during the break.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.