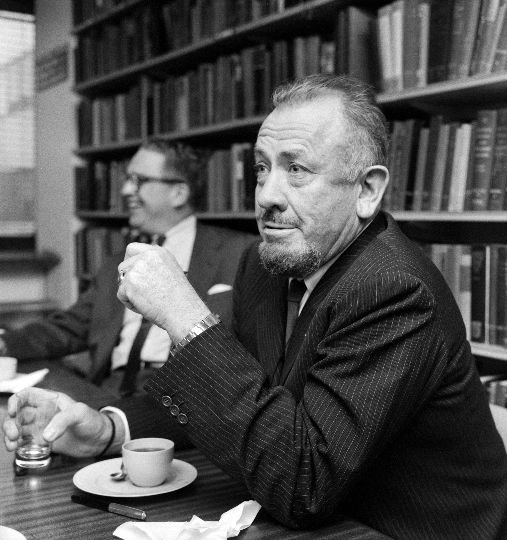

John Steinbeck And The Mystery Of The Humboldt Squid

In 1940, John Steinbeck helped catalog wildlife in the Sea of Cortez. Now, a new creature lurks beneath the ultramarine waters.

A view of the coastline south of Bahía de los Ángeles in the Sea of Cortez in 2004. Credit: William Gilly

“Trying to remember the Gulf is like trying to recreate a dream,” John Steinbeck wrote about the Gulf of California.

On March 11, 1940, Steinbeck, his wife Carol, and his close companion, marine biologist Ed Ricketts, boarded an old sardine fishing boat in Monterey, California and set sail south to Mexico’s Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez. The 76-foot Western Flyer had been converted into a makeshift laboratory for scientific observation, loaded with preserving jars, long-handled dip nets, microscopes, and a hearty supply of beer. As the vessel slipped past the mouth of the bay and headed south into the open sea, it marked the beginning of a historic journey to Mexico’s Sea of Cortez.

“Let us go,” Steinbeck wrote about the voyage, in The Log from the Sea of Cortez, “into the Sea of Cortez, realizing that we become forever a part of it.”

Over the course of six weeks and 4,000 miles, Steinbeck and Ricketts explored the “washtub bluing blue” body of water wedged between Baja California Peninsula and Mainland Mexico. They collected and preserved marine invertebrates, trudged through eelgrass, peeked under rocks to examine intertidal species, and recorded the distribution of the diverse fauna of the Sea of Cortez—from Sally Lightfoot crabs to gray porpoises. Together, they catalogued over 550 species of marine invertebrates. The voyage was eventually documented in two books: the 1941 Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research, co-authored by Ricketts and Steinbeck, and Steinbeck’s 1951 narrative reflection, The Log from the Sea of Cortez.

“Our curiosity was not limited, but was as wide and horizonless as that of Darwin or Agassiz or Linnaeus or Pliny. We wanted to see everything our eyes would accommodate.” – John Steinbeck, The Log from the Sea of Cortez

Steinbeck’s work and relationship with Ricketts had a profound impact on him as well as his writing. In fact, Ricketts inspired the central character “Doc” in the novel Cannery Row, the wise marine biologist who collects specimens in his lab among the sardine canneries in Monterey. Steinbeck even dedicated the novel to him.

More than a half century later, in 2004, riding the same tide cycle as the Western Flyer, William Gilly, professor at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, and a crew of marine scientists, journalists, and writers retraced Ricketts and Steinbeck’s path to see what had changed over the years.

Ever since he first read of Steinbeck’s adventures in 1979, Gilly became fascinated with the idea of recreating the expedition. The two books written about it not only serve as a piece of literature, but also capture part of the Gulf’s ecological history.

Steinbeck was mesmerized by the energy of life in the Gulf, noting in The Log from the Sea of Cortez how “the playing porpoises, the turtles, the great schools of fish which ruffle the water surface like a quick breeze, make for excitement.” The fishermen Steinbeck spoke to along their route called the deep ultramarine blue water of the gulf “tuna water” for the bounty of large tuna prominent in the area.

“I’ve talked to old fishermen who worked in the American tuna fleets out of San Diego [in the late 1940s and early 1950s], and they would go to the Gulf and see schools of tuna,” says Gilly.

The 2004 researchers land at Cabo San Lázaro in Baja California Sur on April 4, 2004. Credit: Nancy Burnett

Today, large schools of tuna in the Gulf are more rare. Tracking tuna with satellite tags show that the fish do not go much farther north into the Gulf than the city of La Paz, located nearer to the southern tip of the peninsula, says Gilly.

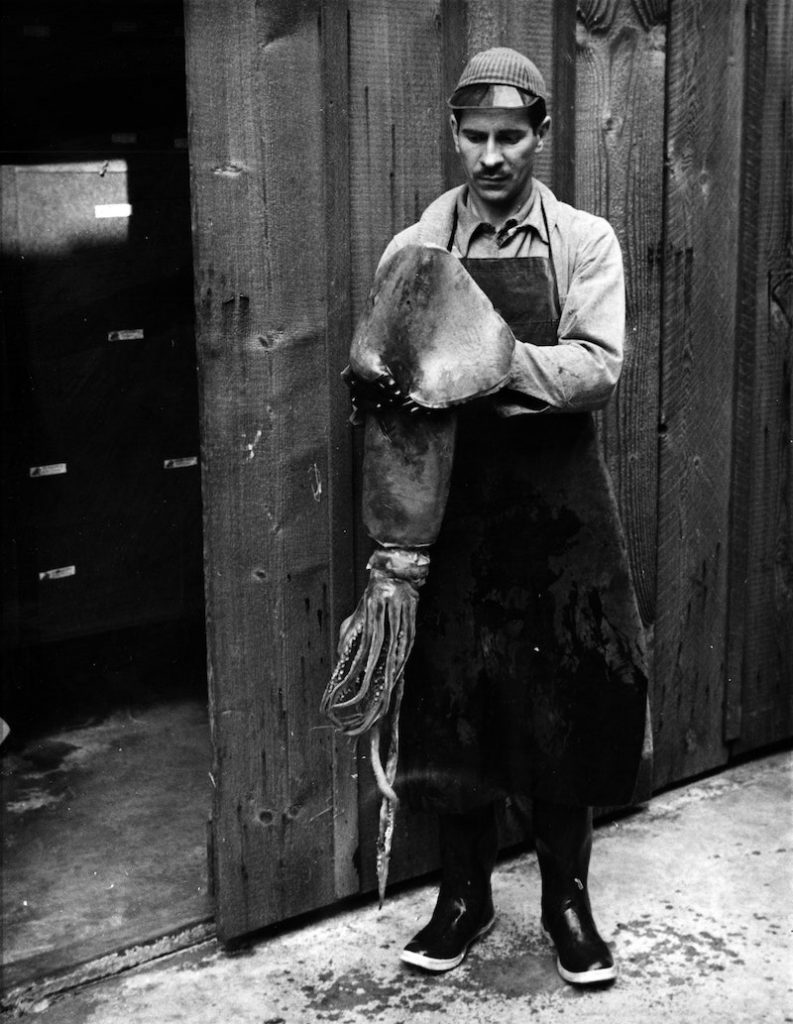

Instead, one sea creature—absent from Ricketts and Steinbeck’s catalogs—now lurks in sometimes massive swarms beneath the Gulf waters: The voracious Humboldt squid, an aggressive cephalopod that can grow up to six feet in length and weigh as much as 110 pounds.

Although those aboard the Western Flyer did not record them in 1940, today, researchers know the Humboldt squid, or “jumbo squid,” reproduce in the southern half of the Gulf of California, with spawnings suspected to occur year-round in the region. The squid is a migratory species historically endemic to the Eastern Pacific. Using Steinbeck’s voyage as a puzzle piece in a complicated timeline, Gilly wants to know when the Humboldt squid expanded into the Sea of Cortez.

The mysterious appearance of the Humboldt squid is one way the Gulf has changed over the decades. While many of the places Ricketts and Steinbeck visited remain pristine today, in some areas Gilly and his team found notable differences in diversity and abundance of species. For example, in Cabo San Lucas, Steinbeck and Ricketts wrote how the tidal zones were “ferocious with life,” and they documented 44 intertidal species. But by 2004, the rocky intertidal areas of the now popular tourist destination were covered in sand. Gilly’s crew identified only 16 species.

“Most of the Gulf’s shores, especially on the islands and on Baja California Peninsula, are not accessed by tourists,” Rick Brusca, an invertebrate biologist at University of Arizona who has researched in the Sea of Cortez since 1969, writes in an email. However, “so many visitors enjoy the Gulf’s tidepools that, in heavily-frequented areas such as the tourist destinations, the seashores have been decimated and are now rather devoid of animal life.”

“There’s been a lot of decline in [species], from baleen whales to squid and sharks and top fish predators,” says Gilly. “Landings of dorado and yellowfin tuna are declining. These are species that are cosmopolitan and huge in numbers, so why they’re declining in the Gulf is kind of troubling.”

Although it is still the most biologically productive region of the Gulf, the upper Gulf has been historically overfished and poorly regulated, says Brusca. The fishing industry hit record catches in 1989, pulling in 90 million tons from the ocean worldwide. Removing top competing carnivores, like tuna, sea bass, and snappers, has changed the food web and perhaps allowed large populations of Humboldt squid to fill in the gap, he says. As fisheries continue to exploit and overfish certain species, “octopus and squids can take over,” says Unai Markaida, a senior researcher studying marine biology and ecology at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, San Cristóbal de las Casas, in Campeche, Mexico.

The crew sample the rocky intertidal zone of Cabo San Lucas, which was mostly covered in sand in 2004. Credit: Nancy Burnett

At first, the presence of Humboldt squid was a concern around the world. Their unexpected appearance in coasts along Oregon, Washington, and Alaska alarmed fisheries and some scientists that the squid were depleting salmon populations. Around the 1960s in Chile, the hake fishing industry saw “the squid as a plague,” says Markaida. Now, the community’s perception and palette has changed. Fisheries began to sell squid to Japanese and Korean markets, and people in Mexico have come up with new recipes for the high protein sea creature, says Markaida.

“You can find jumbo squid from the Gulf of California in markets in Mexico,” says Markaida. “That was unthinkable 20 years ago.”

Despite the abundance of Humboldt squid in the Gulf over the years, they aren’t mentioned in Ricketts and Steinbeck’s logs.

“They don’t talk about seeing squid around the boat in schools, whether large or small,” says Gilly. “That, to me, was surprising because we were in the same place.”

Humboldt squid are best seen a few hours after dusk, explains Gilly. They prefer dwelling in low light conditions, moving up and down the water column throughout the day. The squid spend the daylight hours several hundred meters deep in low oxygen level environments, and only come up closer to the surface at night—sometimes for a few hours, and sometimes all evening. Early one morning, Gilly and the crew “saw hundreds, maybe even thousands near the surface with their tentacles sticking out of the air a little bit.”

“It wasn’t like you really had to look,” he says. “If you were looking in the water, especially at night with a light, you would see squid anywhere north of Santa Rosalia.”

Other squid were present in 1940. The pair recorded sightings of “some small squid” from the family Loliginidae. While Ricketts was not a squid specialist, explained Gilly, he wouldn’t have misidentified the species—he had even held a Humboldt squid in Monterey in 1936.

At first, Gilly and his team speculated that Ricketts and Steinbeck were merely unlucky in seeing Humboldt squid during their journey. “Sometimes you see billfish jumping and sometimes you don’t,” says Gilly. “It’s a matter of luck.”

After fairly consistent numbers since 1997, many people thought that Humboldt squid had taken up a permanent seasonal residence in the Sea of Cortez. However in 2010, Gilly noticed something different. “Before 2010, you had these large squid, and after 2010 you had really small squid.”

Instead of growing up to six feet, mature individuals measured just a foot long—sometimes even less. Gilly suggests that this sudden transformation in phenotype was triggered by the environmental conditions brought by the 2009-2010 El Niño. The winds in the upwelling current are much weaker during an El Niño event, causing the water to be several degrees warmer than normal and nutrient poor, explains Gilly. Algae crashes, leaving less food for plankton and little fish. And this, Gilly explains, puts pressure on the growth of Humboldt squid—but even though they aren’t growing as big, 2013 sonar data supports that they are still very abundant.

All of this gives evidence to the idea that Humboldt squid are an important indicator species whose size and population numbers are clues to the greater health of the Sea of Cortez.

The 2004 vessel, Gus D, in the Gulf at Cabo San Miguel. Credit: Nancy Burnett

Furthermore, Steinbeck and Ricketts’ recordings may be missing signs of jumbo squid because of another climate anomaly. Gilly has considered this hypothesis, but can’t test it because of the lack of reliable and available historical data. Instead, researchers must turn to accounts from fishermen. Gilly estimates that the earliest known date of Humboldt squid in the Gulf of California is 1976, which is based on interviews his team has had with retired fishermen. This leaves the life history of the species in the Gulf a mystery.

“It’s pretty hard to know if there really was a relatively recent historic invasion or not,” says Gilly, who wants to analyze the anoxic sediments of squid beaks to shed light on the historical presence of Humboldt squid in the Gulf. “Or rather, if it has just been episodic invasions that have been happening for tens of thousands of years.”

One clue is that over the last five years, waters have been consistently warm at the depths in which Humboldt squid like to dwell, says Gilly. “As climate change progresses and things get warmer—and the oceanographers say it will happen—this influence will push more into the southern gulf and the squid populations will become less stable.”

“As climate change progresses and things get warmer—and the oceanographers say it will happen—this influence will push more into the southern gulf and the squid populations will become less stable.” – William Gilly

The exact impacts of climate change on Humboldt squid populations are uncertain and difficult to measure. Markaida is interested in teaming with other biologists to continuously monitor environmental variables (sea temperature, salinity, oxygen levels, acidity) to try to better understand which environments are more optimal. Like Markaida, Gilly would like to conduct regular surveys, and send fishermen out twice a month to try and catch squid. After collecting enough squid and environmental data, Gilly and his lab could forecast the abundance and size of squid six months into the future.

“It would be quite important for people’s livelihoods, and they can go undisrupted by these catastrophic losses to the squid fishery,” he says.

Right now, students and researchers are looking at water properties and taking samples to test productivity, says Gilly. “They’re not catching many squid now,” he told Science Friday over the phone this past June. The research vessel has yet to make its way through Santa Rosalia, an area notorious for Humboldt squid.

The Humboldt squid, while known for its aggressive predatory nature and elusive migratory patterns, speak to researchers like Gilly. The presence and physiology of these creatures tell him about about the state of marine environments, indicating changes in climate and nutrient availability over time.

“I think they are telling us right now that the Gulf of California has gotten more tropical,” he says. “They are telling us something is wrong here, something is unusual. California is not a happy place for big Humboldt squid.”

Gilly, other marine biologists, and Steinbeck enthusiasts are lured back to the crystal blue waters of the Sea of Cortez. Currently, a project led by marine geologist John Gregg is underway to restore the original Western Flyer and develop an education and research program aboard the vessel. The reconstructed Western Flyer’s maiden voyage, expected 2019, will return to the Sea of Cortez and revisit Steinbeck and Ricketts’ original journey.

“The Gulf does draw one, and we have talked to rich men who own boats, who can go where they will,” wrote Steinbeck. “Regularly, they find themselves sucked into the Gulf. And since we have returned there is always in the backs of our minds the positive drive to go back again.”

With every donation of $8 (for every day of Cephalopod Week), you can sponsor a different illustrated cephalopod. The cephalopod badge along with your first name and city will be a part of our Sea of Supporters!

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.