From Alberta’s Oil Sands, A Dinosaur ‘Mummy’ With Skin Intact

7:50 minutes

Photo is from the the June issue of National Geographic magazine.

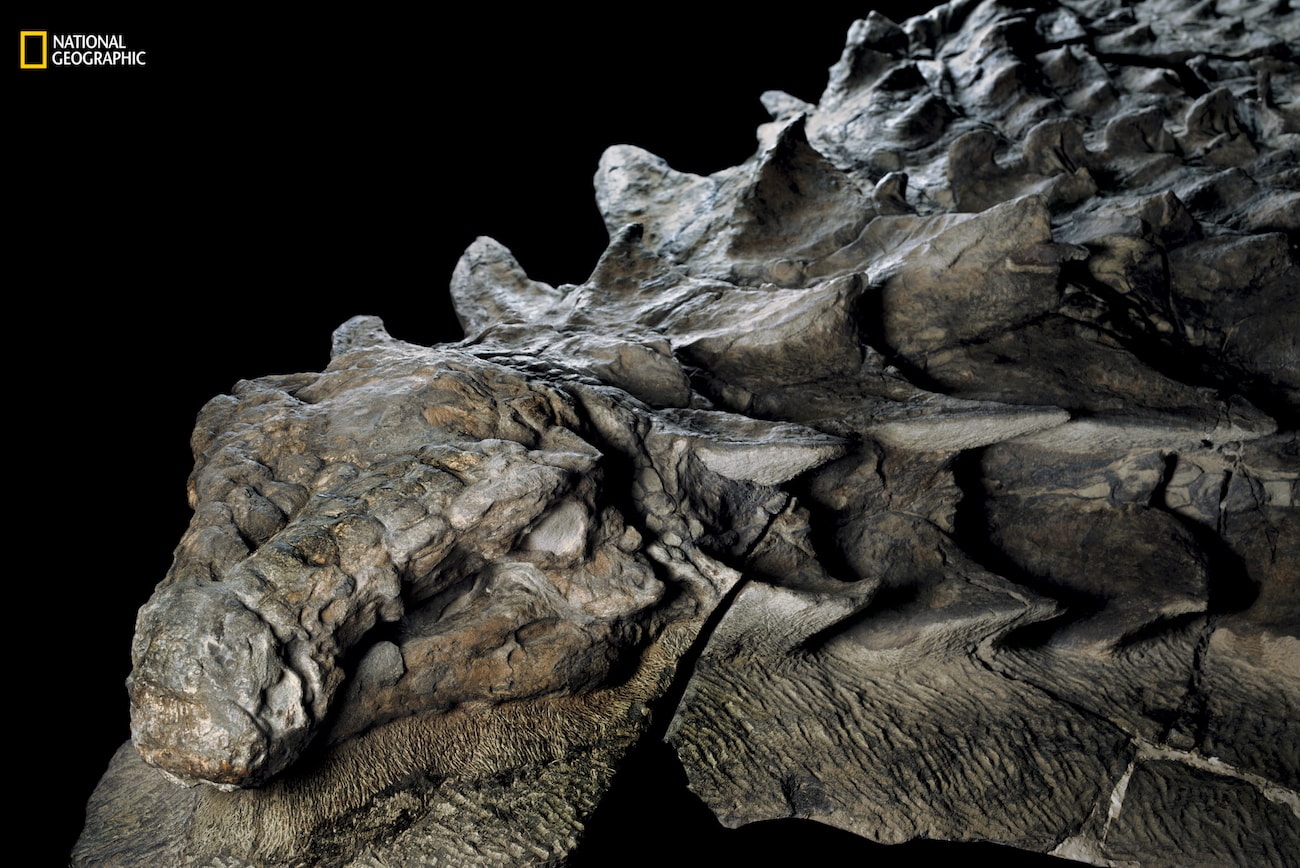

Six years ago, a mining operation in the oil sands of Alberta, Canada, stumbled across the fossilized remains of an armored dinosaur, called a nodosaur. Now, paleontologists have revealed that the find is extraordinarily well preserved: The dinosaur is essentially mummified, with skin, facial expression, and even gut contents intact.

Amy Nordrum, associate editor at IEEE Spectrum, talks with Ira about this extraordinary find and what researchers can learn from studying it. Plus, one of the most isolated islands on the planet somehow also has the highest concentration of plastic debris.

Amy Nordrum is an executive editor at MIT Technology Review. Previously, she was News Editor at IEEE Spectrum in New York City.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I am Ira Flatow.

Six years ago, a worker at a mine in Alberta’s oil sands came across a rock that wasn’t a rock. As it turns out, it was a fossilized dinosaur, complete with preserved skin, soft tissue, and even stomach contents. Paleontologists now studying it are excitingly calling it a dinosaur mummy. Here to tell us more about this fantastic example of preservation, plus other short subjects in science, is by guest Amy Nordrum, Associate Editor of the IEEE Spectrum, here in New York.

Welcome back, Amy.

AMY NORDRUM: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about that. How do you preserve dinosaur skin? It’s not real skin, is it?

AMY NORDRUM: It is real skin.

IRA FLATOW: Fossilized skin?

AMY NORDRUM: So this is actually a very unique specimen. It’s a terrestrial dinosaur that was found in an ancient seabed. So part of the reason that this is so well preserved is it actually died and then, perhaps in a flood from a river or something, it was washed off shore and ended up in the bottom of the seabed, which really helped the preservation process. Typically, terrestrial dinosaurs would not be so well preserved in this way.

So the archaeologists who found it believe that it went under this process called bloat and float, in which the body of the animal floated down the river. The gases in it built up as it decomposed, and then eventually it popped and sunk to the bottom of the seabed. There, it underwent a process, where minerals called carbonates helped to create this hard ossification around the animal and the body and it formed this thing called a concretion, which is sort of like a cement block almost, or a tomb, some people were calling it, for the specimen. And that’s basically what these technicians have been chipping away at the last five years to uncover the fossil that we see today.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, what can we learn from studying this?

AMY NORDRUM: Well, this is a brand new species of a type of dinosaur called nodosaur. So the species itself doesn’t have a name yet, but the class of nodosaur dinosaurs are armored dinosaurs, and this is the most well preserved example we’ve ever seen of this type of dinosaur. So we’re able to actually see the osteoderms, which are the bony plates that form the armor of the animal for the first time. And like you said, there were even some preserved marbles inside that may be, perhaps, that animal’s last meal and may be hinting at the stomach contents of that animal that we can find out through further analysis.

IRA FLATOW: So it’s almost like an ankylosaur. My kids love that, ankylosaurus.

AMY NORDRUM: Yes, it’s a type ankylosaur. Yeah, the nodosaurus dinosaurs are a type of ankylosaur.

IRA FLATOW: OK, let’s go to our next story, which is a little depressing. I mean, I think we’ve seen this on the internet by now, a remote island that is covered in trash.

AMY NORDRUM: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: That floated there?

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right. Henderson Island is an island, one of the most remote in the entire world. It’s basically smack dab in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. There are no roads. There are no people that live on it permanently. And yet, it has piles and piles of trash, 38 million pieces of trash and plastic, estimated by a marine researcher at the University of Tasmania who went over and did a survey of it back in 2015.

So all these bits of trash are on the island but no people. It’s actually the highest concentration of plastic bits found anywhere in the world, at this point. She believes that the trash was carried there through the South Pacific Gyre, which is a giant anti-clockwise ocean current that basically builds up in the Pacific Ocean, and this island is right in the middle of it.

IRA FLATOW: So it sweeps up everybody’s garbage and puts it on this island.

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right, and she says most of the items that she found were consumer goods, things that we think of as recyclable, that were not, in fact, recycled. So she’s finding a lot of things like cigarette lighters, bottles, little pieces from board, games, little plastic pieces, disposable razors, things of that nature.

IRA FLATOW: So of course, everybody’s rushing out to go clean up the island, right?

AMY NORDRUM: We wish. I mean, it is a UNESCO World Heritage site. But you know, clean up efforts, as she says, can really only go so far. We’re producing something like over 300 million tons of plastic per year, globally. So you know, you have to kind of stop it at the source and do more on the production and the consumption side to really prevent this problem from happening in the first place.

IRA FLATOW: This is sort of a very undiscovered sort of island, a tiny little island in the middle of the Pacific. There have got to be a few more, then, with beaches like that, right?

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right. I mean, she’s studying this particular island just with a group of researchers. You know, there are research efforts there every five or 10 years, but in between, there’s basically no one. And it’s part of a group of four islands called the Pitcairn Islands. And the others haven’t really been as closely studied. So there may be even worse conditions on those beaches, if you can imagine.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, somebody will send a drone looking for them.

AMY NORDRUM: That might be a good way to do a future trash survey so you don’t have to actually end up sorting through the trash yourself.

IRA FLATOW: All right, now, let’s move on to something that scientists have answered a question I’m sure we’ve all wondered and that is, if you watch ladybugs– and I have a few at home. They play around my house. How the heck do ladybugs fold their wings so fast, because it’s really almost magical how they do that?

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right. They can deploy their wings in less than a tenth of a second, and then, they can fold them back up in just two seconds. And the crazy thing about ladybug wings is they need to be rigid enough to support their flight, but they also need to be flexible enough to be folded underneath their outer spotted shell that we all see when they’re walking around on the ground.

So scientists at the University of Tokyo decided to take a look at how this was done. They had to invent a rather unique process to do so because typically, the way that the wings are folded, are hidden from sight beneath the outer shell. So they actually transplanted a piece of the shell with an artificial, translucent version of itself. So you’re able to actually see the process take place as it was happening.

So from this, they concluded that the wings of the ladybug actually have creases in them shaped like diamonds. And they’re able to fold their wings over these creases with different lifts in their abdomens. So they use their abdominal muscles to kind of lift the wings and fold them into place and tuck them underneath the outer shell.

IRA FLATOW: Can we imitate that and do something with that knowledge?

AMY NORDRUM: Potentially. It could be really useful knowledge for engineers. So for example, there’s satellites that are being put up into orbit now that are very, very tiny, but they still need antennas that can deploy once they’re in orbit to be able to send communications back down to Earth. And these satellites are getting smaller and smaller so it’s become tricky to figure out a way to fit an antenna in those satellites that will deploy in such a way as to still function. And so NASA’s actually working on several versions of foldable, deployable satellites. Maybe they could follow the ladybug model to help them out.

IRA FLATOW: Call it Ladybug One or something.

AMY NORDRUM: There we go. We’ve already got a name for it.

IRA FLATOW: Hashtag.

Lastly, one for the gardeners, some fishy orange petunias? Tell us about that.

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right. So this week we had some controversy in the petunia world.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, my god. Again?

AMY NORDRUM: Yes, again. Who knew? So these are beautiful flowers. They’re actually sold all over the world. They’re quite popular at weddings. They have these big magnificent blooms. But recently, some Finnish authorities they were finding some petunias with big orange, purple and red blooms, which are not the natural colors of petunia blooms. So they got a little suspicious and started to do some analysis. They actually found that these petunias were genetically engineered and in Finland and in the US, you need a special permit to import and sell a genetically engineered organism. These petunia sellers did not have that permit. So the Finnish authorities have shut down sales.

We’ve also found them since, here in the US, too. So the USDA has told importers and flower distributors this week that if they do have these petunias on hand, they need to get rid of them.

IRA FLATOW: You’re not gonna get busted if you have one in your house, are you?

AMY NORDRUM: No, if you’ve already bought an Orange African Sunset Petunia, as they’re called, the USDA is saying that you don’t need to worry. You can keep it. But yeah, they’re asking those distributors to stop selling them.

IRA FLATOW: Somebody’s gone crazy with CRISPR again. Thank you. Thank you very much, Amy.

AMY NORDRUM: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Amy Nordrum, Associate Editor of IEEE Spectrum They are based here in New York.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.