To Get to Europa, Think Like MacGyver

A look at the idea lab where scientists are preparing for a fly-by mission to one of Jupiter’s icy moons.

Down a nondescript hallway in a building labeled “SCIENCE,” on the scenic California campus of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a group of scientists and engineers are in their lab, watching ice grow inside a stockpot with some foam padding crudely duct-taped to its outside.

This makeshift set-up probably isn’t what you’d expect researchers to be focusing on at a technologically advanced space institution like JPL. But the young, enthusiastic team at the Icy Worlds Simulation Lab is encouraged to think like MacGyver about the important questions they’re trying to answer.

“I’m a big advocate and implementer of rapid prototyping—just build it, prototype it, see what works,” says astrobiologist Kevin Hand, who leads the Icy Worlds Simulation Lab with senior research scientist Robert Carlson. “See what you can learn from that. Do it on low cost, low budget. Go to Home Depot, True Value, or wherever. Get the parts, and see if the experiment makes sense at the most basic level. And then mature it on up from there.”

The lab’s main focus is to search for signs of life on certain icy outer planets and moons of our solar system that might have oceans, including Jupiter’s satellites Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede, and Saturn’s Enceladus and Titan. To that end, the researchers conduct experiments to better understand the physics and chemistry of those worlds, and to see if they can predict what their surfaces might be like.

Their work will help inform future missions to these far-out places. Thus far, we’ve had limited insight into what the frigid surfaces are actually like, save for a few imprecise images beamed back by telescopes and fly-by missions. So members of Hand’s lab—a mix of JPL engineers and scientists, post-docs, and intermittent college students—are creating simulations of the otherworldly terrain so that scientists can better plan how we might some day land on these icy bodies and further study their habitability.

“Since I can’t wake up and go to Europa in the morning, the only other option is to recreate Europa’s surface in the laboratory,” Hand says.

Hence, the ice growing inside a stockpot—yes, the same you’d use to make a giant batch of gumbo. It’s an early attempt at trying to ascertain, for one, if stalagmite-like ice structures called penitentes could form, based on the known conditions on Europa. These formations are common in high-altitude spots on Earth like the Andes. If they exist on Europa, the design of a future lander would have to accommodate them.

Hand, though, isn’t convinced that the models we have to explain penitente formation on Earth apply to Europa. “I think there’s a disconnect between the physics of how icy surfaces on the earth form and how they form and are modified on Europa’s surface,” he says.

And since they started working on the stockpot experiment early last year, the lab hasn’t turned up any features resembling penitentes under Europa-like conditions. But the data was interesting enough that they recently decided to scale up the experiment, graduating from the stockpot to a vacuum-sealed stainless steel chamber dubbed “The Ark of Europa,” for the prized golden chest rescued by Indiana Jones. The new device allows them to control the simulation’s conditions more carefully by altering the time scale, for instance, and by using a special lamp that mimics sunlight.

In a separate, earlier project, the team experimented with which kind of drills or cutters might work best to bore through Europa’s ice, even tooling around with some of the standard drills you can find in your local hardware store. That research led to a prototype that’s now informing the development of future robotic arms at JPL.

“Those kinds of higher-end experiments would never be possible without first doing the kind of scientific and engineering rapid prototyping to answer the basic question first,” Hand says.

In answering these basic questions, they get closer to their ultimate goal. “The big-picture motivation [of this lab] is to advance our capability to seek out and understand signs of life on ocean worlds beyond Earth,” says Hand.

* * *

Ask any space scientist what aspect of the cosmos deserves research attention, and you’ll hear a multitude of responses: Mars, Pluto, exoplanets. But Europa, the smallest of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, has been getting a lot of hype lately.

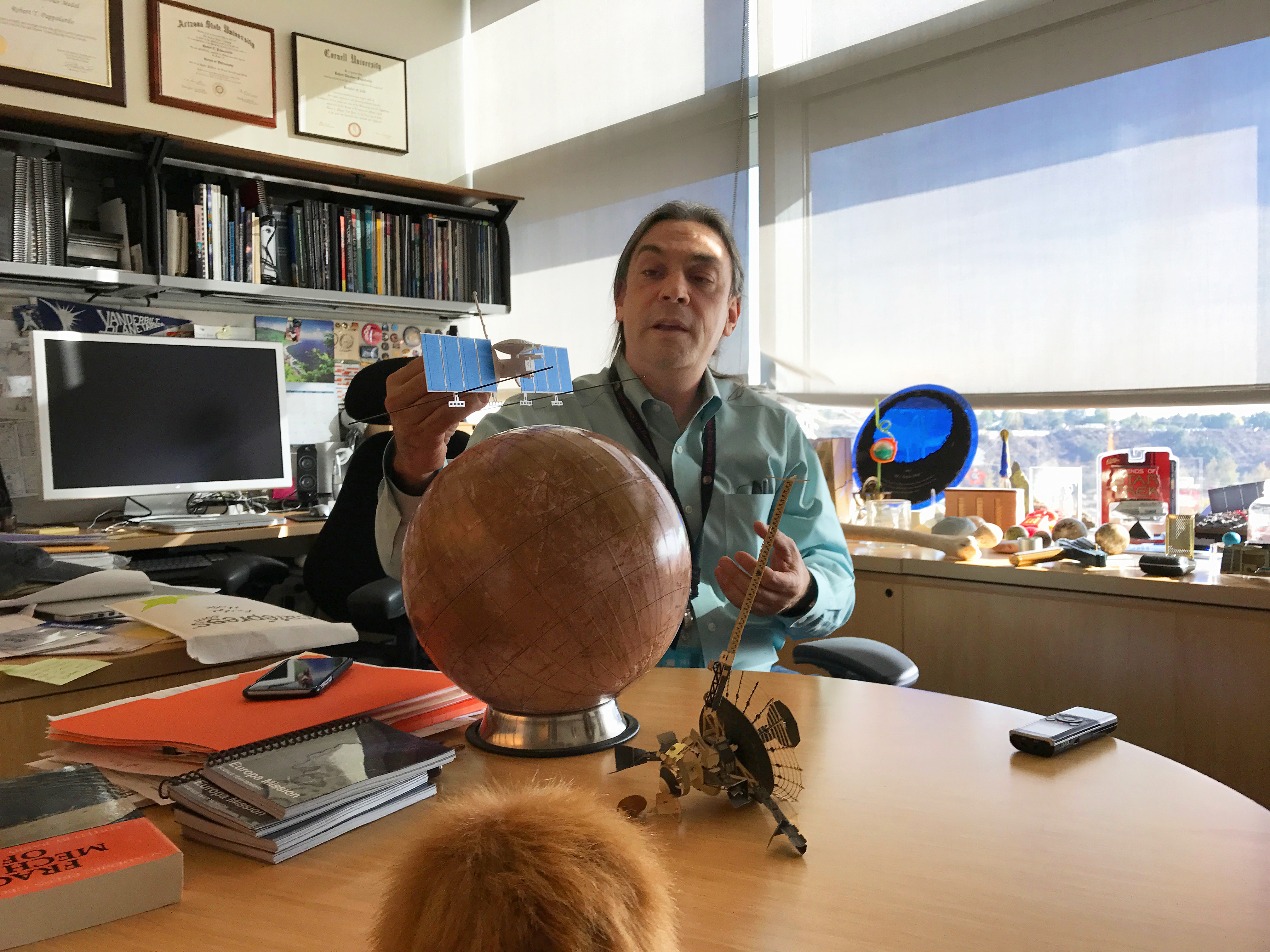

“People knew before that it was weird and interesting, even going back to the ’70s,” says Robert Pappalardo, project scientist for NASA’s upcoming mission to fly by Europa. Data streaming back from Voyager showed that Europa was “fascinating, geophysically and geologically,” he says. But when NASA’s Galileo spacecraft sent back images from Jupiter and its moons in the 1990s and early 2000s, scientists found “pretty direct evidence that an ocean still persists” within Europa. Scientists think that this ocean lies beneath the moon’s icy crust, plunging approximately 62 miles deep.

“When we look at life on Earth as a guide, we see that wherever you find liquid water on Earth, you generally find life,” adds Hand. “So looking out in the solar system for worlds that harbor liquid water, Europa stands out as one of the premier ocean worlds.”

What’s more, there’s evidence of physical and chemical processes occurring on Europa that could play a role in supporting life, such as geochemical reactions between subsurface rock and water or ice. “That water-rock interaction could help provide the elements and energy needed to build and power life,” says Hand. There could also be volcanic activity or low-temperature hydrothermal systems on the seafloor, or geophysical processes happening in the ice shell, which could provide the conditions and materials conducive to life.

Scientists are hoping to gather clues about whether or not Europa could support life in the upcoming fly-by NASA mission. The spacecraft (it has no official name yet) is slated to launch as soon as 2022, and could potentially arrive at the satellite as early as 2026.

The spacecraft will be equipped with nine main instruments, including spectrometers, magnetometers, cameras, and a radar. The plan is for the spacecraft to orbit Jupiter and use its gravity, and that of the Galilean moons, to do multiple fly-bys of Europa, all in about 3.5 years.

Mission scientists are also preparing for the possibility of launching some kind of lander soon after sending off the probe, so that researchers can more quickly apply the information being projected back.

If the spacecraft were to detect a hotspot of geological activity, for instance, or a region with evidence of organic materials, “then that might be the place that we want to send a future lander,” says Pappalardo. “But we’ll see how that plays out.”

* * *

The scientists at the Icy Worlds Simulation Lab are trying to anticipate and prepare for any kind of scenario a future spacecraft might encounter.

“If someday we send something to the surfaces of these icy worlds, we better darn well know what the surface morphology is like,” laughs Amy Hofmann, a research scientist and the lab’s manager. In a later email, she wrote, “We’re hoping that the results from our (necessarily) small-scale (in time and space) experiments will enable us to develop models to predict what we might expect to occur on Europa at much larger spatial and temporal scales.”

And in a decade or so, we could get some confirmation.

“For the first time in the history of humanity, we actually have the tools and technologies to go out and do the exploration that could answer this very fundamental question of whether or not biology works beyond Earth and whether or not we are alone in the universe,” Hand says. “And I think the best place to go to answer the question of whether or not we’re alone is Europa’s ocean.”

Chau Tu is an associate editor at Slate Plus. She was formerly Science Friday’s story producer/reporter.