What It’s Like to Walk in Space for the First Time

Astronaut Mike Massimino describes his first spacewalk during the famous mission to repair the Hubble telescope.

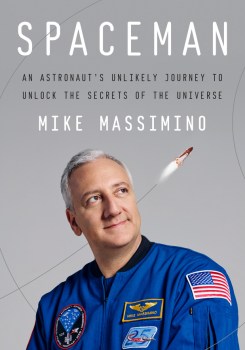

The following is an excerpt from Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe, by Mike Massimino.

When people ask me what it feels like the first time you spacewalk, what I tell them is this: Imagine you’ve been tapped to be the starting pitcher in game seven of the World Series. Fifty thousand screaming fans in the seats, millions of people watching around the world, and you’re in the bullpen waiting to go out. But you’ve never actually played baseball before. You’ve never set foot on a baseball diamond before. You’ve spent time in the batting cages. You’ve run drills and exercises with mock-ups and replicas. You’ve spent months playing MLB on your Sony PlayStation, but you’ve never once set foot on that mound. And guess what? The Series is tied and the whole season is on the line and everyone is banking everything on you. Now go get ’em. That’s how I felt sitting in that airlock.

I watched the clock tick down, anxiously waiting for it to get to zero. Finally it did. Once the pre-breathe was over, we unhooked our suits and we were floating. Then Grunsfeld floated over to the airlock’s inner hatch and pushed it closed. He pulled the handle down and spun it shut. It sounded like I was being locked in a prison cell. WHOMP! CHA‑CHUNK! I looked over at Newman like I guess this is it. There’s no going back now.

At that point we were clear to go. Newman pulled open the door to the payload bay and pushed the thermal cover aside. Then he went out first to make sure the coast was clear and to secure our safety tethers. He was out there for a few minutes. Finally he said, “Okay, you’re clear to come out.” I put my hands on the hatch frame and pulled myself through. I was floating on my back, looking up and out of the payload bay. The first thing I saw was Newman floating above me, hanging out with this grin on his face like Check this out.

Behind his head was Africa.

According to my suit’s biometric sensors, I have a normal resting heart rate of 50 or 60 beats per minute. The moment I saw the Earth it spiked to 120. Eventually it settled back down to a normal exercise rate of around 75, but for that moment it was racing. Hubble is 350 miles above Earth; we need the telescope as far away from the planet as possible in order to have a longer orbit, see more of the sky, and be farther away from the atmospheric effects of Earth. The space station is 250 miles above Earth. From that vantage you can’t fit the whole planet in your field of vision. From Hubble you can see the whole thing. You can see the curvature of the Earth. You can see this gigantic, bright blue marble set against the blackness of space, and it’s the most magnificent and incredible thing you’ve ever seen in your life.

Seeing the Earth framed through the shuttle’s small windows versus seeing it from outside was like the difference between looking at fish in an aquarium versus scuba diving on the Great Barrier Reef. I wasn’t constrained by any frame. The glass of my helmet was polished crystal clear, and every direction I looked, there was nothing around me but the infinity of the universe. I was really out there, floating in it, swimming in it. I felt like a real spaceman.

After seeing the Earth, I looked down the payload bay at the telescope, and the thing I noticed was the light from the sun. The sun on Earth is filtered through the atmosphere; it can appear bright yellow or as that golden hue you get at sunset. In space, sunlight is nothing like sunlight as you know it. It’s pure whiteness. It’s perfect white light. It’s the whitest white you’ve ever seen. I felt like I had Superman vision. The colors were intense and vibrant—the gleaming white body of the shuttle; the metallic gold of the Mylar sheets and the thermal blankets; the red, white, and blue of the American flag on my shoulder. Everything was bright and rich and beautiful. Everything had a clarity and a crispness to it. It was like I was seeing things in their purest form, like I was seeing true color for the first time.

After taking a minute to soak everything in, my first conscious thought was How the heck am I going to get anything done? How am I supposed to pay attention to my work with this magnificent beauty all around me? But then I turned my head back to the wall of the payload bay right in front of me and there was a handrail. I recognized it. It was just like the handrail I’d seen and worked with in the pool dozens of times. I looked around and everything in the payload bay was right where it was supposed to be. Every tool, every piece of equipment, the winch with the rope on the end of it—everything felt familiar. Even though I’d never been out on that pitcher’s mound before, I knew exactly what I needed to do.

It was time to go to work…

Reprinted from Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe © 2016 by Mike Massimino. Published by Crown Archetype, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Mike Massimino is a former NASA astronaut, author of Moonshot: A NASA Astronaut’s Guide to Achieving the Impossible (Hachette Go, 2023), and a professor of Professional Practice in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Columbia University in New York, New York.