Reaching for a Space Rock, Nanoparticles in the Brain, and a Missing Audio Jack

6:44 minutes

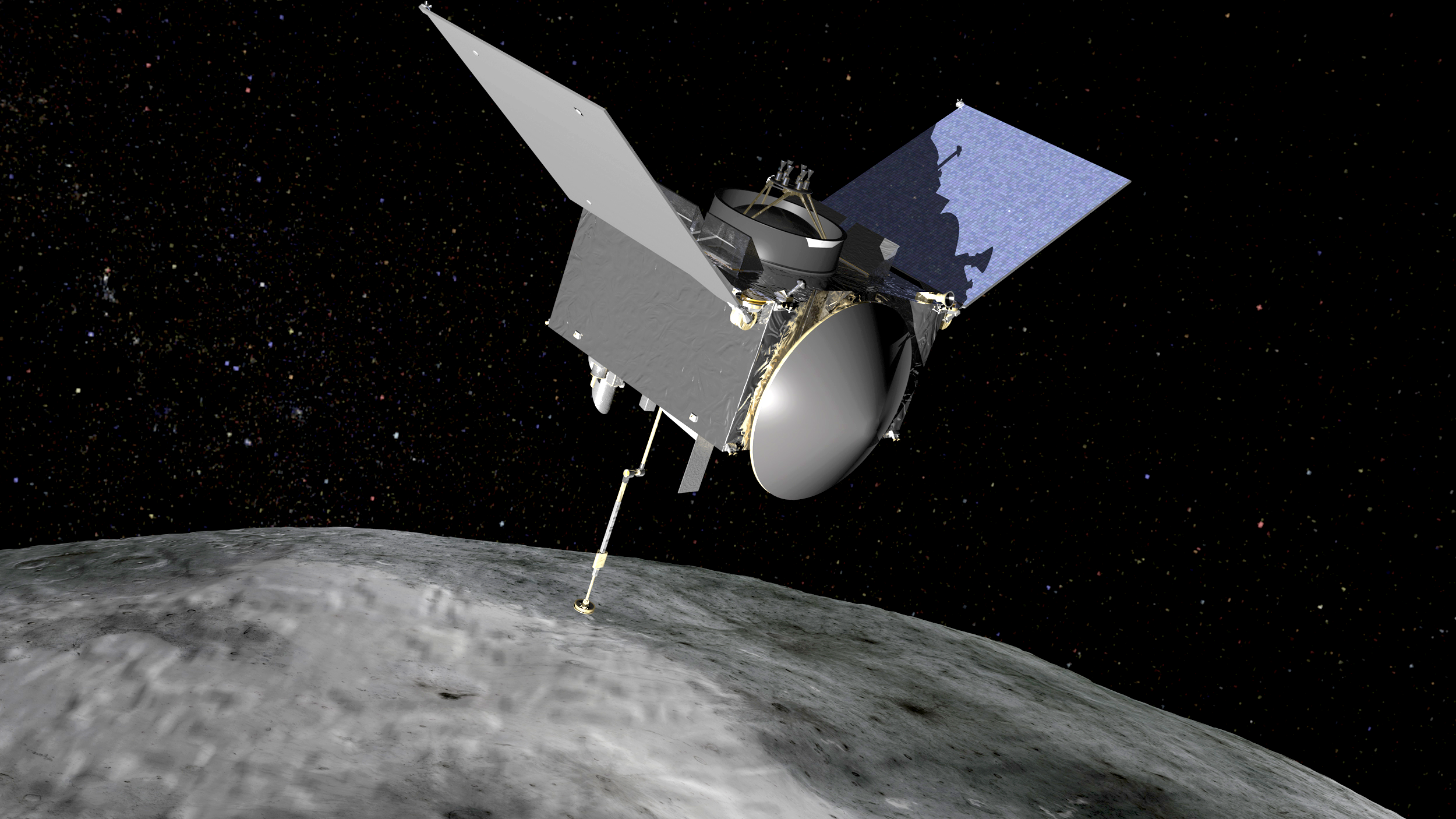

On Thursday, NASA launched an Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral bearing OSIRIS-REx, a space probe on a mission to the asteroid Bennu. If all goes according to plan, the craft will rendezvous with the asteroid, collect a sample, and return it to Earth in 2023. Researchers are interested in knowing more about the composition of the asteroid, which will pass within the Moon’s orbit in 2135. IEEE Spectrum journalist Amy Nordrum describes the mission, as well as other stories from the week in science and technology, including one about Apple’s new iPhone design.

Amy Nordrum is an executive editor at MIT Technology Review. Previously, she was News Editor at IEEE Spectrum in New York City.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Yesterday, an Atlas V rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral in Florida carrying a space probe named OSIRIS-REx. And if all goes well, it will be coming back again in about seven years with a sample from an asteroid. It’s going to land on an asteroid and pick some stuff up. That’s exciting.

Let’s talk about it with Amy Nordrum. She’s an associate editor at The IEEE Spectrum in New York. Welcome back, Amy.

AMY NORDRUM: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about this. Sounds cool.

AMY NORDRUM: It is cool.

IRA FLATOW: Very geeky.

AMY NORDRUM: It is. Absolutely. So this is a mission to an asteroid. The asteroid is called Bennu and NASA is headed there to take a look at what is known as a primitive asteroid. So this asteroid will tell us a lot about the origins of the solar system.

When the solar system first formed, about 4.5 billion years ago, this asteroid formed along with it and has pretty much remained intact since that time. So this hopefully, by taking a few rock samples from the surface of Bennu and bringing it back here around 2023, NASA scientists will get a better idea and a better look into what the original composition of the solar system might have been.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any fear that this asteroid might hit Earth as it travels?

AMY NORDRUM: There is. So this asteroid is actually passing within relatively close range of Earth, as far as asteroids go, about every six years. And then there’s going to be an event, in about 2135, where the asteroid will pass within the moon’s orbit.

And we’re not really sure how this could change the orbit of the asteroid itself. But by taking a little bit of a better look at the asteroid’s orbit today and understanding how the reflection of the sun, and the absorption of heat, and the thrust that provides the asteroid today, that will help them also get an idea of how that orbit might change in 2135, which could give us clues as to whether or not it’s actually going to ever run into the Earth.

IRA FLATOW: And hopefully, by then, we’ll have some way of changing orbits of asteroids so they don’t hit us.

AMY NORDRUM: Maybe we’ll be able to intercept it and send Bennu on its way. We hope so.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s move on to Apple unveiling the next generation of their iPhones. Nobody expected a whole lot, did they? It’s kind of a quiet lead up to it.

AMY NORDRUM: So Apple hasn’t made a lot of dramatic changes. I mean, the iPhone was first released in 2007 and there have been certainly changes and upgrades over the years and the generations. The big news this time around, when the iPhone 7 was announced on Wednesday, is that you will no longer have a headphone jack. The traditional analog audio jack that we’ve all relied on to plug-in our headphones is gone from the new model.

So what you’ll do, instead, is you’ll use the lightning port, which is the currently the port that you’re using to charge your iPhone. You actually have to have new headphones that plug into that port, which Apple is going to ship with every new iPhone. But this caused a little bit of controversy among longtime Apple customers.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you know, the jack goes back like over 50 years. It’s the same size as in my old transistor radio. So it was actually the biggest part, the thickest part holding it back from getting any skinnier.

AMY NORDRUM: Right. Absolutely. So Apple’s argument here is that customers are going to be better off in the end, because the analog output wasn’t that great at transferring power, whereas as the digital lightning port can do that very well. And what that allows is for you to create things like headphones that have more functionality along with the sounds. And in addition to producing sound, they can also do things like maybe monitor your heart rate or your activity level while you work out. You can expect more and more powerful headphones to come along, eventually.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. It’s exciting, though. And then there’ll be– I’m sure other people have already wireless headphones.

AMY NORDRUM: Wireless headphones.

IRA FLATOW: Competitors.

AMY NORDRUM: Right. And even a couple of Chinese manufacturers have already eliminated that headphone jack, so you can expect others to follow.

IRA FLATOW: Hit the road, Jack.

[LAUGHTER]

There’s news this week about the nanoparticles in the brain. Right?

AMY NORDRUM: Right. So there’s a couple of researchers from the University of Lancaster who have taken a couple of brain samples from both Lancaster and Mexico City. And they’ve analyzed these brain samples for magnetic particles. And then they’ve taken a look at what exactly magnetic particles have made their way into the brain.

And what they found there was magnetite nanoparticles. And these are particles that are– some of which are originally produced in the brain. They tend to be spiky. Even the brain itself is producing these nanoparticles.

But they’re also present in air pollution. And those particles tend to be more spherical. So for the first time, these researchers have found spherical magnetite nanoparticles in the brain, which they believe made their way there through the nose cavity and into the brain from air pollution. So this is possibly a reason to be concerned.

IRA FLATOW: And we don’t know what the long-term effects of these things.

AMY NORDRUM: No, we don’t. We do know that the magnetic magnetite nanoparticles that are present in the brain biologically, naturally, the researcher I spoke with, she has a theory that they’re enveloped in possibly like a biological membrane that keeps them somewhat benign. But the magnetite nanoparticles that you actually breathe in through your nose, potentially, they would not have that protective membrane that she theorizes is there. So they might actually be causing more problems and things like free radicals that may or may not be linked to neurodegenerative diseases. They’re going to be following up on some of that research.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That’s kind of a little scary there. And then also, finally, there’s this breaking bandicoot news. Breaking. This just in. Tell us what that is.

AMY NORDRUM: So the bandicoot is this small marsupial that’s found in Australia and Tasmania. And some researchers were curious about the fact that, for some reason, the bandicoots in Australia seem to be pretty good at avoiding domestic dogs. They stayed out of the yards when there was a dog nearby. But the ones in Tasmania they found weren’t so great at that.

So they were wondering, well, why would the bandicoots in Australia pretty much know to avoid dogs but the ones in Tasmania aren’t afraid of them? And the answer, they think, is that dingos have long preceded dogs in their presence in both Australia and Tasmania. And dingoes look a lot like dogs. In fact, they’re thought to be evolved from the domesticated dog that has gone wild in that area. Come down from Asia.

So their theory is that since dingoes are present in Australia and not in Tasmania, there’s been this really interesting case of co-evolution, where the bandicoots that are preyed upon by dingos in Australia are much more accustomed to dog-like features or dog smells or something and they know to avoid those yards, whereas those in Tasmania have never had that privilege.

IRA FLATOW: So how long do they go back?

AMY NORDRUM: So dogs have been there about 200 years and dingos have been there about 4,000. And cats have only been there for 200 also. And pretty much all the bandicoots are pretty bad at avoiding cats. So that’s like a brand new challenge for them to be able to figure out.

IRA FLATOW: Avoiding the cats.

AMY NORDRUM: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Are they lunch for cats?

AMY NORDRUM: They can be, yeah. The bandicoots are preyed upon by dogs, cats, dingos. It’s tough to be a bandicoot.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I guess it is. It’s not tough to Amy Nordrum. She knows a lot of stuff. Thank you, Amy.

AMY NORDRUM: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Amy Nordrum, associate editor of IEEE Spectrum here in New York.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.