Tracking the Hidden Trail Left by Your Smartphone

16:38 minutes

Each call, post, or search from your smartphone leaves a trail of hidden digital data that you might not see, but which can be collected by organizations interested in your info. Patrick Mutchler, from Stanford University, tested how much information can be extracted from phone metadata and shares his findings with Science Friday. And information security specialist Lenny Zeltser discusses the privacy policies of Google’s GBoard, and other keyboard apps.

Patrick Mutchler is a Ph.D. candidate in Computer Science at Stanford University.

Lenny Zeltser is an Information Security Specialist and a Senior Faculty Member at the SANS Institute in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

Your phone let’s you communicate and in many, many, many different ways. You can tweet. You can text. You can post. And if you’re old school like me, you might even make a phone call every now and then.

But your smartphone is also communicating in a hidden way. It’s working behind the scene, so to speak. Take metadata.

Edward Snowden’s leaked documents show that the NSA was collecting phone metadata. Not the contents of your calls, but the other types of information contained in each communication. The who, the when, and the where. And after Snowden revealed the federal collection program, the NSA backed off and changed its guidelines.

So where do we stand? Have these changes increased our privacy? And what can you really learn from this metadata?

A team of researchers put the NSA’s new guidelines to the test. Their results were published this week in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

My next guest is here to tell us what they found. Patrick Mutchler is the lead author on that paper. He’s also a PhD candidate in computer science at Stanford University. Welcome to Science Friday.

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Hi there. How’s it going?

IRA FLATOW: Hey. Pretty good. Edward Snowden’s leak happened in 2013. So what changes were made to the NSA, the metadata surveillance program after that time? What has changed?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: So last summer, the USA Freedom Act was passed. And this actually restricted the ability of the NSA to examine the data that they’re collecting. And also required the telecom, so companies like AT&T and Verizon, to store the metadata themselves, which the NSA can access, rather than the data being stored in databases within the NSA.

IRA FLATOW: And you tested how much information you could get under these new guidelines. You created an app to do this. Tell us about that, how you studied that.

PATRICK MUTCHLER: That’s right. So if we want to study the privacy properties of telecom metadata, we need some metadata to test. So we built an app that allowed volunteers to give us their metadata. We had about 800 participants who gave us about 250,000 phone calls and 1.2 million text messages that we could analyze for patterns.

IRA FLATOW: And you were able to find some very specific information from these call logs. For one person you were able to find a health condition. How do you do that?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: That’s right. So you could imagine the businesses that you call in your daily life reveal some information about you. So we’re able to take the database of just phone numbers, it’s raw phone numbers and when phone calls are made, identify the businesses that those phone calls– those phone numbers belong to. And then from that, we can learn interesting things about people.

In the case of this one person, he was making phone calls to a medical reporting service that was related to cardiac arrhythmia. And it also made phone calls to a cardiologist. And we were able to confirm with public records that this person did indeed have a cardiac arrhythmia. So from the metadata, we could predict a medical diagnosis that we were able to confirm sort of through other channels.

IRA FLATOW: So you can– it all converges someplace and you can find that convergence? Could you find what doctor that person was seeing?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: It depends really on the particulars of the individual. Metadata analysis we can think of it as finding patterns. And maybe those patterns are apply to every single person. But in general, they can be used to identify certain patterns of behavior that are indicative of kinds of activity.

IRA FLATOW: And you also found out something about someone’s gun preferences.

PATRICK MUTCHLER: That’s exactly right. In a similar sort of way, we found a person who had been in contact with a firearms dealer and also with a customer service line for particular brand of firearm. And we were able to confirm in addition with this person that he had in fact purchased this kind of firearm.

IRA FLATOW: Could you, if you wanted to find out people who buy assault rifles, could you do that?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Certainly our research suggests this is plausible. Doing it in a totally automated fashion and doing it with high success rates is something that we don’t just– we don’t know yet. There’s sort of needs to be more in-depth research done. But our results indicate that this is a potentiality.

IRA FLATOW: The tools you’re using to figure out this type of information, is it something anyone can access?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Generally, yes. The research that we did was just a few of us in an office with limited resources and publicly available databases and Google searching. So this is information that if you had someone else’s metadata, you could perform this snooping just as well as we did.

IRA FLATOW: So if you see someone’s phone number, you can type in into Yelp or Google and search all around Facebook and find out all this information?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: That’s exactly right. So just think of the Yellow Pages, but now we have the internet to do these sorts of things. So Google and Yelp both provide free services where you can type in a phone number and see if there are businesses that belong to that phone number. And Facebook does a similar sort of thing where you can type in a cell phone number in the Facebook search bar and it might pop up a person’s profile. So you can identify the owners of phone numbers in this manner.

IRA FLATOW: It does work. You can do that, huh?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Yeah. We find that you can nail about 30% of phone numbers people’s call logs just from these totally automated sources.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. You found one number can be connected up to 25,000 people.

PATRICK MUTCHLER: That’s exactly right. So the way the NSA program works is that they were able to look more closely at individuals who are connected in some way to a suspected terror threat. And the rules for how they define connected closely are a little strange. But basically we were able to evaluate in our paper exactly what a little closely means. And it turns out that as of right now, a single person in this database can be connected a little closely to about 25,000 individuals.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. You looked at phone and text records. And we use our phones for more than just calls now. Are we leaking out more metadata these days?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Certainly there’s more to that metadata than just telephone metadata. There’s internet metadata is another topic of intense discussion among security and privacy activists. Our study in particular just looked at telecom metadata. But that isn’t the only kind of metadata that exists.

IRA FLATOW: You found these hubs that are connecting us together. Tell us about those.

PATRICK MUTCHLER: That’s exactly right. So we think about the telephone connectivity graph as sort of being related to a social graph. You only call your friends, and maybe your friends sort of form a tight knit group.

But in actuality, there are these massive businesses that call large numbers of people or are called by large numbers of people. Think about spam phone calls for example. You may have been called by the same spam phone call as someone who lives totally across the country from you and who you’ve never met before. And this connects you to this person through this spam phone call.

And these massive hubs like spam phone calls, or if you receive tweets on your phone from Twitter, these sorts of things connect large numbers of people through the call graph.

IRA FLATOW: Does this stuff frighten you at all? That we can find so much so easily?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: I think everyone can make up their own opinion now given the facts, right? We’ve had a discussion about metadata for several years. And there hasn’t been a lot of public science about the actual reach and effectiveness of these programs. And now given more information, people can make a more informed opinion about the state of the policy we have today.

IRA FLATOW: Spoken like a politician. OK. So what’s your next step? Where do you go from here?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Well, certainly our study is limited by the number of people that we were able to collect metadata from. And we only had about 800 participants. If we were to have a larger database of metadata and sort of more precise information about our participants, I suspect that we’d be able to do even better in our inferences. We’d sort of have more precise results that were more accurate about what we can learn about individuals.

It would be nice to see if we could more closely match the resources of government organizations, rather than the resources of just two graduate students in an office.

IRA FLATOW: So who’s going to help you doing that?

PATRICK MUTCHLER: I think this is a job for future scientists. You know, it’s not just us working on this sort of problem. But anyone who is interested in taking up the charge for understanding metadata privacy is happy to work on this sort of thing.

IRA FLATOW: And there’ll be lots of charges for that. So we hope you get some. Thank you Patrick.

PATRICK MUTCHLER: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: And good luck to you. We’ll wait to see what else to come up with. Patrick Mutchler is a PhD candidate in computer science at Stanford University.

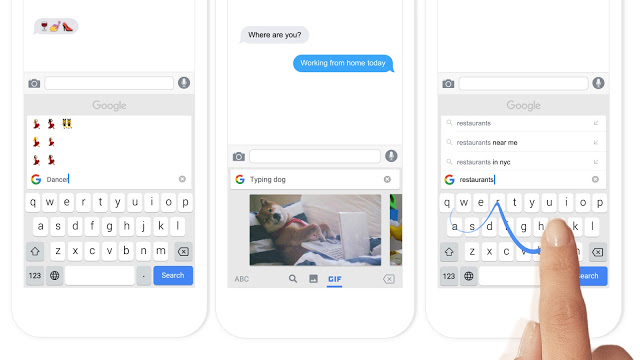

Another vulnerable spot on a smartphone for data leaks are apps. Google just released a keyboard app for the phone called Gboard. Places a little Google search icon right on the keyboard.

Hey, now you don’t need to leave the Google world, right? Yeah. You can stay right in their world and Google gains a little bit more data about you.

My next guest is here to fill us in on some of these apps. Lenny Zeltser is an information security specialist based out of New York. And he also writes a blog focusing on information security and IT trends at Zeltser, Z-E-L-T-S-E-R.com.

He joins us here in in our community studios. Welcome to Science Friday.

LENNY ZELTSER: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: I’m sorry about your name, Lenny.

LENNY ZELTSER: I like my name. I’m not sorry at all.

IRA FLATOW: Very good answer. You analyze lots of software and security issues. What did you will find out about these third-party keyboards for your phone? What catches your eye about this?

LENNY ZELTSER: Well, it’s fascinating to observe how companies are trying to innovate and provide value to users of mobile phones that in turn allow these companies to receive some value back. And a big change occurred on the iOS platform about a year and a half ago. When for the first time, Apple allowed third-party keyboards into its walled garden.

And I became very curious what kind of information do these keyboards try to capture from the users. And what I found was that some keyword manufacturers are being very upfront, while others perhaps are not quite sure themselves regarding what data they’re capturing from the user. And this could be a very vulnerable spot for people typing sensitive data using those keywords into their mobile phones.

IRA FLATOW: Because when you install a third-party keyboard, the first warning you get is kind of scary. It says, if you’re granting full access, press this button. And we’re going to take everything we can.

LENNY ZELTSER: Yeah. The word full access, especially in iOS, is I think purposefully selected by Apple to make sure the person knows exactly what it is they could potentially give up. Now, the extent to which the application developer actually takes advantage of the full access, well, that depends from app to app.

You mentioned Gboard just a few moments ago. And the innovation from Google there is that you can use the keyboard just like you would use any other keyboard. But also on top of the keyword, you can type your search queries. And this way you can interact with Google search without ever leaving the current application.

And in that case, Google is being very upfront with its users. Telling them that as with any search engine, when you type your query, they will be able to see it.

But on the other hand, they clearly state that they do not capture the key strokes that you’re typing. And according to Google, that information stays within your phone. That might comfort some users of this particular third-party keyboard.

On the other hand, when you look at some of the keywords that you can install into your phone, keyboards like SwiftKey key or Swype, in that case, they do capture some information. And they tell their users, sometimes in a very plain way, sometimes in a very oblique way, that they could receive some information that you’re typing, and store them and process them on their servers.

And that’s where I get a little bit concerned. And I get concerned not so much by the possibility that the big companies will misuse my data willingly, although they could. But I tend to be a trusting individual. My concern is if that data is available and stored somewhere outside of my phone, then what measures do these companies take to protect the data from somebody else accessing it and misusing it?

And I find that when you try to look into any public commitments that these companies made for protecting your data, there’s almost no details beyond vague statements that refer to security best practices and some vague certification commitments.

IRA FLATOW: Talking with Lenny Zeltser on Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, about these new keyboard apps. So while Google is like the 800 pound gorilla, you’re saying that at least they’re transparent. And you feel that they’re keeping track of your security better than some of the other apps.

LENNY ZELTSER: Yeah. At least Google has a very, it’s actually surprisingly nicely clear and easy to understand privacy statement that it’s related to this keyboard. Have you ever tried to read some companies privacy statement? It is just–

IRA FLATOW: I haven’t got the time.

LENNY ZELTSER: It’s fascinating. When you can’t fall asleep, it’s one of those things that you probably might want to pull up. These privacy statements usually are legalese because they have to be.

But in the case of that particular app, Gboard, it was nice to see a clear statement regarding what isn’t and what is being collected. And of course, some people might trust that the company will fulfill those commitments. But maybe other people will not be as trusting.

In the case of Gboard specifically, it was interesting for me to see some research that’s was published on the Macworld site. Where the researcher Glenn Fleishman was actually monitoring the network while using the Gboard keyboard to see under what circumstances data gets transmitted to Google servers. And he confirmed in his experiment that indeed, when he’s typing, nothing gets transmitted unless he’s typing specifically a search query.

IRA FLATOW: When you grant them full access, what kind of stuff are they pulling off?

LENNY ZELTSER: Well, on iOS, and that’s usually when people talk about privacy implications of keyboards, it’s iOS but they’re most worried about because traditionally that’s very secure and a walled garden. On iOS, when you say grant full access, what you’re essentially allowing the keyword to do is interact with the network. And that becomes the big deal.

Because if the keyboard that you installed can’t interact with the network, that means that it can do whatever it wants with your data that you’re typing into it, but it has no way to transmit the data off your phone. If you allow full access, that means it can transmit the data to the company servers. And that’s where data leaks could potentially occur.

In the world of computers and mobile devices, people are worried that they’re going to be spied upon. And they might be worried about, let’s say, malicious keyloggers that are capturing everything that you’re typing and stealing the data. Well, a keyboard is potentially the perfect keylogger if the data is being misused.

IRA FLATOW: There goes all of your codes and everything that you want to keep secret. if they’re logging your keys.

LENNY ZELTSER: Now, the good news on the iOS platform at least is that even if you installed a third-party keyboard, the Apple operating system will not invoke it whenever you’re typing a password. So this is an interesting way that Apple is perhaps protecting the user from themselves.

IRA FLATOW: You told me you like Microsoft’s keyboard.

LENNY ZELTSER: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: SwiftKey, right?

LENNY ZELTSER: Yeah It’s an interpersonal choice which keyboard you end up installing and which keyword you end up liking. And a lot of these keyboards try to entice you into installing them with their own way of innovation.

The keyboard that I use is– Microsoft actually has a couple of keyboards. The one that I like is called Word Flow. And the reason I like it is because I type on my phone with one finger a lot. And so that keyboard is positioned on the screen in a diagonal manner that makes it very easy for me to use my thumb while typing. And that was the feature that enticed me.

But other keyboards allow you to, let’s say, type the first few letters of the word. And they will automatically predict what it is you’re trying to type, which can be a bit eerie.

While other keywords also allow you to not even bother lifting your finger from the screen. And you just kind of swipe it around doodling on the screen, pointing towards the letters that you want to type. And they’ll throw it in for you.

IRA FLATOW: Take home message though is be aware when you press the data access, you’re giving them your data.

LENNY ZELTSER: Indeed.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Thank you Lenny. Lenny Zeltser is an information security specialist who writes a blog focusing on information security at IT trends at Zeltser, Z-E-L-T-S-E-R.com. Thanks for joining us today.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.