That Emoji You’re Sending Is Open to Interpretation

11:55 minutes

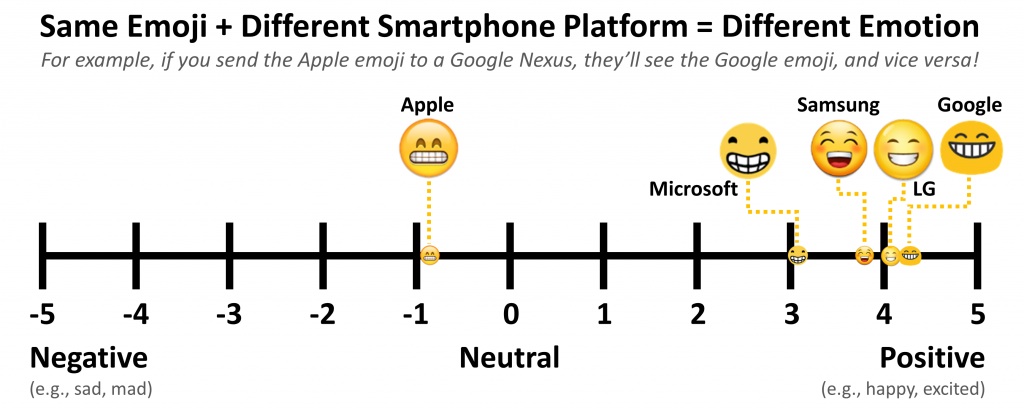

A new study finds that emoji, the tiny graphic images increasingly used in text communications, can be interpreted in a variety of ways. Researchers at the University of Minnesota found that, due to differences in graphic design, certain characters could convey a slightly negative emotion when rendered on one mobile phone platform but a slightly positive emotion when viewed on another platform. And the problem is not just a matter of translating from Apple-ese to Android-ese. Even within one phone system, different users could interpret a single character in a range of ways. Study author Hannah Miller and Internet language expert Gretchen McCulloch discuss the challenges of changing communications in the online world, and what might be done to prevent emotional content from being lost in translation.

Hannah Miller is a PhD Student in the Computer Science and Engineering department at the University of Minnesota – Twin Cities in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Gretchen McCulloch is a linguist and writer. She gave a presentation on linguistics and emoji at the 2016 SXSW conference. She’s based in Montreal, Canada.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow. By now, you’ve certainly become familiar with emojis– you know, those tiny graphic images– the smiley face, the frown, the thumbs-up– that you insert into your text message. But has this ever happened to you? You send a nice, smiley happy emoji from your cell phone, but when it shows up on your recipient’s phone, it looks more like someone’s gritting his teeth. It is not the meaning then you intended.

Well, a new study documents that effect, that emoji can be interpreted in a variety of ways. Researchers at the University of Minnesota found that due to differences in graphic design, certain characters could convey a slightly negative emotion when rendered on one mobile phone platform but a slightly positive emotion when viewed on another platform. And it’s not just a problem of translating between Apple-ese and Android-ese. Even within one phone system, different users could interpret a single character in a range of ways. Wow. Joining me now to discuss the challenges of changing communications in the online world and what might be done to prevent emotional contact being lost in emojinal translation are Hannah Miller, a PhD student in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at the University of Minnesota, and one of the authors of the study. Welcome, Hannah.

HANNAH MILLER: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: And Gretchen McCulloch, a linguist and writer specializing in language online. She gave a talk on the linguistics of emoji at the recent South by Southwest festival. Welcome, Gretchen.

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: And if you’d like to get emojinal with us, you can call us. Our number is 844-724-8255. Hannah, how much could people be confused by these emoji?

HANNAH MILLER: What we saw is that people can be confused both in terms of sentiment– so emotion and semantics, and how they would describe it. And overall, we saw over 40% having people differ by more than two radians on a sentiment scale, from negative 5, or really negative, to positive 5.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And where do the characters come from? Is there no standard design so we all see the same thing?

HANNAH MILLER: I’m really glad you asked that, because technically there is a standard, through the Unicode consortium. But all they provide is the code that will allow it to transfer between the different platforms and the name. So for example, the grinning face with smiling eyes would be all that the different companies have to try to comply with to make their own rendering. And that’s why we see such different interpretations for the different renderings.

IRA FLATOW: So phone designers are free to meet whatever they want to interpret it as.

HANNAH MILLER: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Gretchen McCulloch, were you surprised by this?

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: I’m not surprised at all. I think this is a great study, because it really confirms what a lot of people have been saying anecdotally, that they’re not sure what all emoji mean, or their friends’ emoji look different on their Android than on their iOS device. And I think that putting some concrete numbers to a study like this is hopefully something that will lead to better understanding and maybe even better standardization of what these emoji look like across different platforms.

IRA FLATOW: So what’s your take on why there is all this confusion? Gretchen.

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: I think one of the biggest reasons is that certain emoji especially are influenced by Japanese manga standards for what facial expressions look like. So the smiling eyes, the kind of pointy-looking flat eyes that like a caret symbol on certain emoji are influenced by Japanese manga conventions that say, this is what a smiling eyes character looks like.

And if you’re not very familiar with manga, and many people in the Western world aren’t, you don’t really look at those eyes, and you look instead at the mouth, and the mouth looks flat. And we know that the flat mouth is not supposed to be smiling. So I think that cross-cultural differences in what a conventional emotional representation looks like in a smiley face are something that sometimes leads to this misunderstanding.

IRA FLATOW: Heather, are there any technological solutions to this– standardized, somehow?

HANNAH MILLER: Yes, I think our lab is really interested in looking at what we might be able to do on the technical side. And you can envision building tools such as, for example, maybe being able to see what the rendering was intended to look like. So when you’re viewing it, having the ability to see what the sender had sent on the other side, or possibly even more sophisticated tools, like being able to automatically detect the likelihood that a certain rendering may be construed differently on another platform.

IRA FLATOW: Who decides what emojis become standard? Who decides what becomes an emoji?

HANNAH MILLER: I believe that’s on the Unicode consortium side, because they adopt the different Unicode into their standard. And they have an informing board that decides that. But we actually don’t have much insight into that. And it would be really interesting to hear the Unicode perspective.

IRA FLATOW: Gretchen, sometimes when we create things, they have unintended consequences. Have the emojis morphed into that twilight zone, where they started out being one thing but suddenly they’re being interpreted in a different way?

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: I think nobody really anticipated that emoji would become as popular as they were. Initially, emoji were designed to solve this problem that people were sending picture messages to each other. And that takes up a lot of space, particularly in earlier devices. And so they thought they’d standardize some of the most common picture messages that people were sending, and then also adding a bunch of ad hoc symbols that were found in fonts like webdings and wingdings and things that were on, like, conversions of emoticons from platforms like AOL and MSN, INstant Messenger. And all of these things kind of came together in this conglomeration. No one sat down and said, I’m going to design a typology of all the pictures I think people are going to want. Those pictures got added in a very ad hoc sort of manner. And now they’re taking on this additional life, in some cases as so what people are using them for.

IRA FLATOW: Our number, 844-724-8255 if you use emojis or want to talk about them, or you could tweet us at SciFri. I learned today that the plural of emoji is emoji. Is it emo-JYE, or just emoji?

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: I think that’s an interesting question, because when English borrows in a word from another language– and emoji comes from Japanese– we’ve historically done two different things. Sometimes we add an s, so we say, tsunami/tsunamis. And sometimes we don’t add an s. So we say sushi and still sushi. So with emoji, I think what we’re going to do is still up in the air. And some people prefer one or the other. I know the Unicode consortium does say the plural is emoji, but you definitely hear people saying emojis as well.

IRA FLATOW: And then there are some people who say that emoji are a new language, but they’re not, are they?

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: I like to think of emoji as like facial expressions, tone of voice, gestures– all those things that you add on as a kind of paralinguistic, extra information on top of the literal words you’re saying. And just like you wouldn’t want to have a conversation with your hands tied behind your back and a paper bag over your head and in a monotone, it’s more enriching to have a conversation that involves emoji rather than just plain words that you’re sending to someone.

IRA FLATOW: Hannah, this week Android said that it would be redesigning some of its emoji in an upcoming operating system update, making things a little less blobby. A good idea?

HANNAH MILLER: I do think it’s a good idea. And I think it’s important for the– since we have shown that there is this opportunity for varying interpretation, that they work together to try and converge on what people will be able to agree on.

IRA FLATOW: Let me go to the phones, our number 844-724-8255. Skip in North Little Rock, Arkansas. Hi, Skip.

SKIP: Hi. Longtime listener.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. I make a great deal of use emojis on Facebook and other media. And I know what they have added a bunch of new ones over time. I am so frustrated that with of the interesting designs, they’ve never come up with a decent hug,

IRA FLATOW: A hug. You want to give somebody a hug and you can’t.

SKIP: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: What a great, great– well, Hannah, Gretchen, can we start a movement to get a hug emoji going?

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: Well, there have been several campaigns to add new emoji. There was a Kickstarter to add a dumpling emoji, which was ultimately successful. And I think Taco Bell spearheaded an effort to add the taco emoji. So certainly people have successfully campaigned at en emoji, if that’s something that you want to get into. And I think a hug would be a great idea.

IRA FLATOW: What do you think, Hannah? Do you agree?

HANNAH MILLER: She actually took the examples right out of my head. I had heard about the taco and the dumpling, so definitely if you want one added, go ahead and make it happen.

IRA FLATOW: How much of this is a problem in the greater scheme of things of how we talk and text? How much of having not the right emoji should we be worrying about?

HANNAH MILLER: I think that that’s something that our lab is– we’re glad you asked that, because people are really reacting, because we’ve shown that this opportunity for miscommunication can occur. But we don’t necessarily think that it is so severe that World War III is going to happen because of emoji. And like Gretchen was saying earlier, they supplement our other language. We use them with a surrounding context.

And that’s something that we want to look in the future is– I mean, for this study we looked at them standalone. And can looking at them in context, does that change the way that people interpret them, and can it disambiguate and possibly mitigate this problem?

IRA FLATOW: And is there something I can do to make sure that the emoji that I send won’t get misinterpreted?

HANNAH MILLER: I think the thing is that this study has created awareness of the fact that it might turn out differently on different platforms. And so just thinking about that and thinking, maybe, who are you sending this to and what device might they see this on, you could even look up what they will see it as. And so just now you can have that awareness that people might be seeing different things and interpreting it different ways.

GRETCHEN MCCULLOCH: I think one of the other things that I liked about the study was that it showed which emoji are more or less misinterpretable. So you guys found that the hard eyes emoji wasn’t very misinterpreted, but the grinning face with smiling eyes emoji was misinterpreted a lot. And so to my mind that says, well, use hard eyes and don’t use grinning face with smiling eyes. Pick a different one if you want to be happy.

HANNAH MILLER: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Do you ever have the little fear that just as you figure out the emoji problem, emojis are going to be passe– we’ll be on to the next thing because it’s–

HANNAH MILLER: We’ll be on to the next thing. I mean, maybe a little bit. But we’ve been showing– or there’s stats out there that emoji are super popular and they’re growing in popularity. So for the time being, I think it’s very relevant research.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well, they’re cute and we all use them, so we’ll stay with it as long as people like it. Thank you both for taking time to be with is today. Hannah Miller, PhD student in Computer Science and Engineering Department at the University of Minnesota. Gretchen McCulloch is a linguist and writer specializing in language online. Thanks again for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.